LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this module, the paramedic will be able to:

The first documented historical group debrief is thought to have been performed during the Second World War by Brigadier General Marshall (Gardner, 2013). It was found that when soldiers recounted events from combat, including feelings, decisions and outcomes, they gained psychological benefits. This was termed ‘spiritual purging’ as it was thought to cleanse one’s actions during combat (MacDonald, 2003). Later, the commercial aviation profession used debriefing practices to aid movement away from a hierarchy culture to improve reliability and safety in the late 1970s (Rivera-Chiauzzi and Lee, 2016).

Conducting and participating in a debrief after a critical incident is now commonplace and embedded within the professional standards of paramedic practice (Health and Care Professions Council, 2014).

By definition, a debrief is a post-experience analytic process (Lederman, 1984). It is also considered to be a discussion and analysis of an experience, where lessons learned are evaluated and integrated into one’s cognition and consciousness (Lederman, 1992).

It is acknowledged that because of the nature of prehospital practice, clinicians can become involved in often challenging and demanding situations (Sterud et al, 2006). This includes regular exposure to traumatic situations such as fatalities, violence and aggression (Regehr et al, 2002). Recurrent contact with both psychological and physical trauma increases the risks of stress, burnout, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as a multitude of other mental health disorders.

While exposure to trauma may be an occupational hazard, this does not negate the legal and moral responsibility of employers to protect workers from anticipated psychological trauma (Greenberg, 2001). The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 stipulates that employers must reasonably and practicably protect the safety and welfare of their employees at work.

The key to safeguarding the needs of service users and clinicians alike lies with identifying strategies to protect the physical and mental wellbeing of paramedics exposed to trauma (O’Keeffe and Mason, 2010). Post-incident debriefing is thought to be the key to cultivating emotional resilience for navigating such trauma (Tannenbaum and Cerasoli, 2013).

In the prehospital environment, a post-incident debrief often comprises an informal conversation between colleagues who attended the incident (Halpern et al, 2014). A more structured model of debrief also occurs within healthcare environments and often requires an impartial facilitator as well as the whole clinical team.

Debriefs should be used as a non-threatening and relatively low-cost way to evaluate unanticipated outcomes, identify learning opportunities, protect patient safety and act as a cathartic measure (Rivera-Chiauzzi and Lee, 2016).

The formality of the debrief can be varied to suit participants. It should be split into three areas—description, analysis and application (Mackinnon and Gough, 2014).

Ideally, it should be a friendly, honest discussion with the aim of identifying behaviour, decisions and perceptions to improve future results (Fanning and Gaba, 2007). According to a meta-analysis conducted by Tannenbaum and Cerasoli (2013), engagement in debriefing improves the performance of clinicians who take part. The predominant function is to identify areas of positive and negative performance and work together to determine ways of improving future performance (Kessler et al, 2014).

Fostering learning through debriefing: the theories

The process of conducting a debrief is very much intertwined with reflective practice. Active learning is acquired through experiences, processing and assimilating lessons learned into perspectives, attitudes and behaviour (Dyregrov, 1997). The more relevant the experience is to personal and professional goals, the more meaningful such learning is regarded to be (Knowles, 1996). Essentially, the act of debriefing is the key to unlocking reflection. If participants can gain something productive from their experience, they are much more likely to regard it as a positive experience and foster resilience (McLeod, 2017).

The theory behind debriefing springs from Kolb’s experiential learning theory and Lewin and Schein’s change theory (Gardner, 2013). In Kolb’s (1984) cyclical model, the participant starts learning through engagement with a concrete or known experience. The second stage comprises reflective observation and leads towards the third stage, a period of self-reflection and facilitated discussion. The purpose of the third stage is to assist the individual to conceptualise, make sense of and gain a deeper insight into the experience and implications for future incidents. Finally, there is experimentation, where the participant implements changes during a later experience, which they can reflect on and acquire further knowledge, continuing the cycle.

Debriefing after an incident gives the participant opportunities to start this cycle and gain a deeper understanding of and insight into their own clinical practice, with the aim of improving and protecting patients (Allen et al, 2018).

Lewin and Schein’s 1996 change theory also details the link between action, debrief and learning (Gardner, 2013). This theory describes a dynamic ‘unfreezing’ with a transition to ‘refreezing’ process that results in change. Unfreezing refers to the recognition that traditional action no longer works, and extinguishing habitual techniques or processes. The participant must endure transition, a difficult relearning phase where thoughts, perceptions, feelings and attitudes are restructured (Brett-Fleegler, 2012). Finally, this restructuring allows for acceptance and assimilation of new knowledge to challenge the norm.

Using reflective learning methods in a debrief engages participants in deeper discussion where they can unlock rationales for decisions, behaviour and actions (Kessler et al, 2014). Open and impartial reflection is not an easy task and carries a risk of inciting negative feelings of guilt and denial, as well as a loss of confidence in clinical practice (Rudolph et al, 2001).

Nonetheless, the concluding adaptations to practice can have dramatic, positive outcomes whether they are in patient care, professional development or emotional intelligence and resilience. Recognising and understanding the contributions to an outcome is a vital step towards development and improvement (McLeod, 2017). Post-incident debriefing is the first step in this process of active learning.

Debrief categories

The subtle difference between debriefing and defusing is an important consideration when discussing categories of debrief.

Defusing is a form of critical incident management. It is used immediately after an incident to manage emotional distress and acute trauma reactions in staff (Sandhu et al, 2014). A debrief has more structure and aims to review the whole incident, considering communication, information, equipment, emotional, personal or environmental factors.

Debriefs can be divided into two categories—hot and cold. A hot debrief is performed straight after the incident, when all individuals involved are present (Shore, 2014). For hot debrief to be successful, it should take place immediately after the event, so the optimum level of information can be retrieved and priority issues identified (Rivera-Chiauzzi and Lee, 2016).

The timescale is of utmost importance to ensure that the recall of information is less susceptible to bias. However, if a debrief is undertaken in the middle or at the end of a shift, there may not be adequate time to conduct it competently. In addition, some practitioners may not be emotionally ready to discuss the event (Kessler et al, 2015).

A cold debrief takes place several days after the event. This allows individuals to reflect on details of the incident and process their emotions (Weathers, 2017). Giving individuals time may make them more open to the debriefing process (Shore, 2014). Cold debriefs involve the collation of a greater amount of quantitative data and patient information, including from staff who may be able to contribute but were not present at the incident (Kessler et al, 2015).

Irrespective of timing, or whether they are hot or cold, it is imperative that debriefs occur in a safe, neutral environment (Rivera-Chiauzzi and Lee, 2016). This reinforces the intention to develop an understanding of actions taken and the move away from an investigation to find blame.

Barriers to cohesive debriefing

Barriers that obstruct and inhibit cohesive debriefing can include time constraints and a lack of structure (Sandhu et al, 2014). If participants are not given the space and time to debrief adequately, this may incite feelings of frustration, compounding the negative effects of the original traumatic incident.

Kessler et al (2015) suggested that a major restriction on the quality of debriefing was the lack of a trained or qualified facilitator. Sandhu et al (2015) also found that the skill of the debrief facilitator affected quality. In support of this, research has found that team authority figures often take the role of facilitator; and while this initially appears beneficial as they can share clinical knowledge or experience, it can also lead to bias in the discussion (Kessler et al, 2015). A potential solution would be to have an independent facilitator but this may not be practical in a prehospital environment.

Effective debriefing is believed to be a learned skill that requires formal training and practice. Sandhu at al (2014) suggested that this requires a multifaceted approach. Adaptations to improve leadership, integrating debriefing into practice and education on the importance of a debriefing could promote a culture change to prioritise this practice. While learning in practice is common, the danger of having an inexperienced or insufficiently trained facilitator is that the debrief could morph into creating a list of mistakes, which does not allow motives, perceptions and human factors that have influenced decisions to be explored (Kessler et al, 2015). A fault-finding mission after emotive work can quickly escalate into clinicians becoming defensive and reluctant to engage.

Clinicians who are reluctant to engage are another barrier to productive debriefing. It is vital that the facilitator of the debrief is sensitive to the emotional state of the participants. An adrenalin response to traumatic or stressful situations can elicit a range of emotions, including exhaustion and negative feelings. Individuals who are unfamiliar with debriefings may be apprehensive about the process and will be reluctant to talk about emotions and areas of improvement (Shore, 2014). Negative previous experience may cause staff to think that debriefs are ineffective or a waste of time (Healy and Tyrrell, 2013).

Most researchers agree that to have effective discussion where new knowledge is acquired, participants must be willing and open to engagement (Scott et al, 2013). When there is concern about criticism, fault finding or blame, the discussion is less likely to include pertinent issues (Salas et al, 2008).

When conducted efficiently, debriefing promotes united, collaborative working within a department. It promotes peer support between colleagues and therefore reduces the possibility of psychological harm from talking about the event, which in turn gives validation to the experience and the emotions raised (Huggard, 2013). In this way, it can also improve staff resilience and help to strengthen coping mechanisms (Jackson et al, 2007). It also gives time for the opportunity to identify individuals experiencing an acute stress reaction who are more likely to go on to develop a chronic disorder (Wessely and Deahl, 2003). Therefore, it improves self-awareness and knowledge of crisis management.

Time constraints can be a significant threat to cohesive and productive debriefing. Shore (2014) reported that allowing time and gathering staff members together in a clinical environment is not always easily to achieve. Supporting this further, Nadir et al’s (2017) research showed that staff felt a lack of time while on shift was the biggest deterrent to conducting and engaging in a debrief. Along with time restrictions, a lack of facilitator training and designated space as well as uninterested colleagues all posed barriers to cohesive debriefing (Nadir et al, 2017).

A debrief should not be seen as a luxury or as an indulgence. It is the final phase of the patient’s care and the foundations of future care. It is the inspiration for further research and medical ingenuity. Most importantly, it is how practitioners can recognise achievement, resolve errors and restore emotional resilience. If time is not set aside adequately, the debrief will not become a priority and, without that, none of these things will be achieved and time will be wasted.

Debrief model

Much literature on the benefits of debriefing for the medical community is available but templates or structures for a hot debrief are rare.

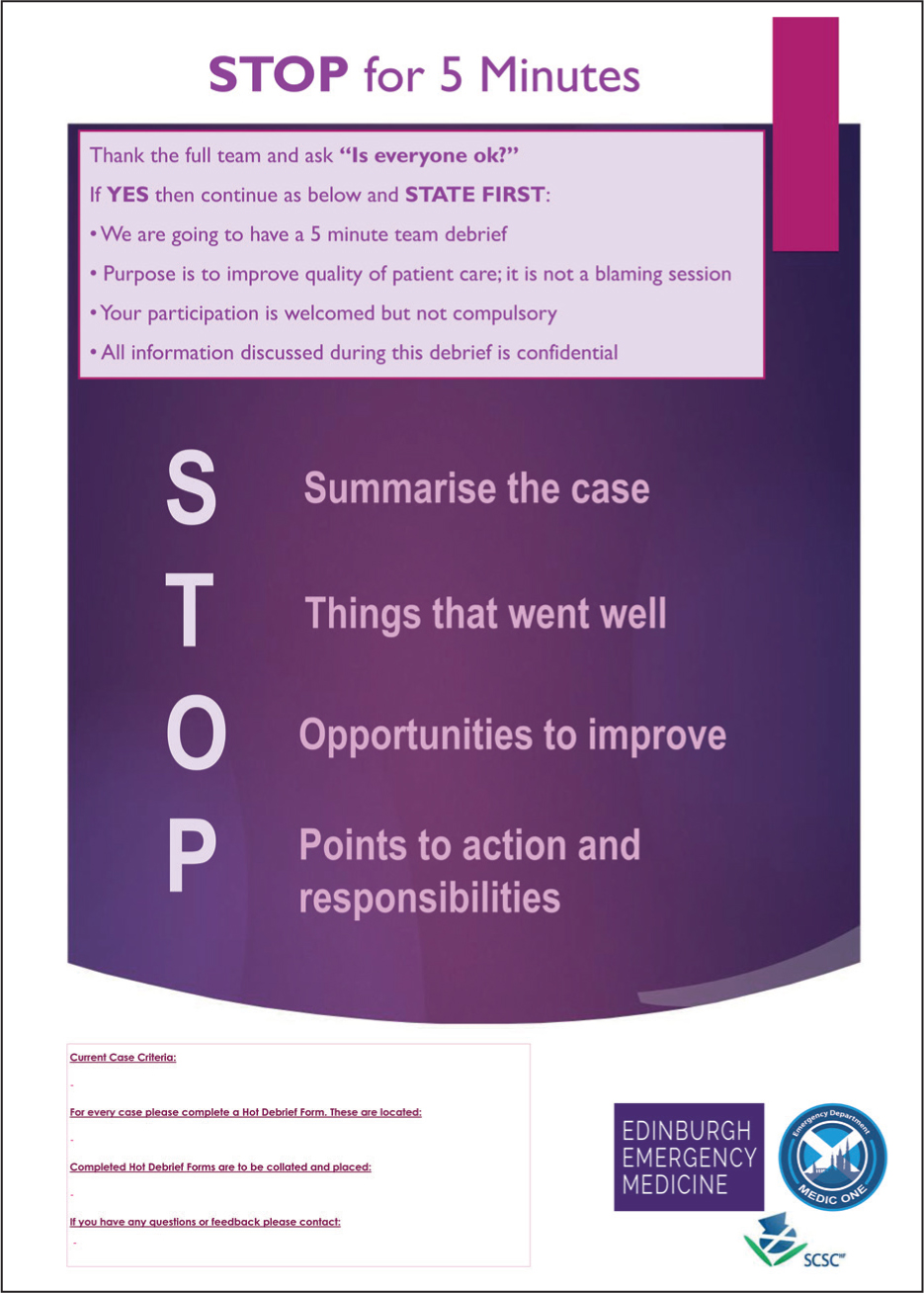

Walker et al (2018) (Figure 1) formulated their own hot debrief structure for a European Society of Emergency Medicine conference. They found that while debriefs were beneficial in their emergency department, structured models were lacking in current literature. Their ‘Stop 5: stop for 5 minutes’ hot debrief model abbreviates four main points of discussion, making it compact, memorable and easily accessible for prehospital care. These are:

The model’s initial section directs how the debrief should be initiated and the first step is asking: ‘Is everyone OK?’ The benefit of this is that it formally promotes prioritising the emotional needs of the clinicians involved. This may help to negate emotional barriers to debriefing by allowing clinicians to seek emotional space if they need it. This question also provides validation for negative emotions by acknowledging that individuals may be distressed and not ready to debrief.

More harm than good?

There are concerns that conducting an immediate post-incident debrief can contribute to long-term PTSD (Paterson et al, 2015).

Some would argue that the effectiveness of psychological debriefing and other early interventions remains a contentious area of mental health research (Wessely and Deahl, 2003).

Bisson et al (1997) found that among their sample of burn trauma victims, 26% of the debriefing group had PTSD at a 13-month follow-up compared with the 9% control group that received no intervention. Mayou et al’s (2000) conclusion supported Bisson et al’s (1997), suggesting debriefing had persistent adverse effects on road traffic incident victims.

One idea is that it is not the debrief itself but the way in which it is delivered that causes harm. Forcing individuals directly or indirectly to participate can be as traumatising as the original trauma for those who need isolation and solitude at that time (Everly et al, 2002). Both Bisson et al (1997) and Ehlers et al (1998) agreed that in-depth discussion of the traumatic incident soon after occurrence increased the risk of developing PTSD.

If a participant is engaged without consent, this may add to emotional distress experienced at that time. Flannery et al (1991) offered an optional debrief programme for psychiatric staff who had been assaulted during a shift. Their research found that after 90 days and 62 debriefings, 69% of participants felt they had regained a sense of control after their trauma. Later on, Jenkins (1996) examined the outcomes of voluntary debriefing with emergency workers after a mass shooting incident. Those who attended a debrief initially reported more symptoms than who had declined participation, but they also recovered more from depression and anxiety.

A Cochrane review (Rose et al, 2002) analysed 11 studies comparing psychological debriefing with ‘no intervention’ controls. It found that there was no evidence that debriefing reduced general psychological morbidity, depression or anxiety. The report concluded that compulsory debriefing of victims of trauma should cease (Rose et al, 2002).

Further criticism of published literature supporting post-incident debriefing includes claims that reports of satisfaction over debriefing experiences are often confused with objective measures of traumatic stress prevalence (Burns and Harm, 1993). There is evidence that group debriefing sessions may increase the risk of PTSD and permanently distort the participants’ memories of events (Paterson et al, 2015). The main body of criticism of post-incident debriefing rises from Mayou et al (2000) and the Cochrane review (Rose et al, 2002). Mayou et al (2000) noted that their intervention ‘had limited internal structure’. Despite this, there is a widespread belief that these two studies prove that debriefing is harmful (Hawker et al, 2011).

Following the Cochrane Review (Rose et al, 2002) recommendations, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2005) guidelines stated: ‘For individuals who have experienced a traumatic event, the systematic provision to that individual alone of brief, single-session interventions (often referred to as debriefing) that focus on the traumatic event should not be routine practice’. However, it was recognised that this might not apply to debriefing of groups after mass trauma or of emergency workers. Later, these guidelines were revised to state that psychologically focused debriefing should not be offered for the prevention or treatment of PTSD (NICE, 2018).

Single-session debriefs may also cause harm indirectly by fostering complacency by assuming the debriefed individual will now be immune to psychological disorder. The concept of debriefing was not conceived by psychologists as a standalone intervention but part of a complex stress management procedure with adequate long-term assessment (Wessely and Deahl, 2003). Single-session, post-incident debriefing is not recommended for the psychological prevention or treatment of PTSD by NICE (2018); however, debates continue in research on the potential benefits of debriefing to practice improvement.

Randomised control trails (RCTs) are difficult to achieve ethically in the real world of crisis and disasters; therefore, a blend of qualitative and quantitative experimental designs are more likely to produce valid results (British Psychological Society, 2002).

The RCTs examined in the Cochrane review (Rose et al, 2002) evaluated whether debriefing reduced symptoms of PTSD (Hawker et al, 2011). Hawker et al (2011) argued that, fundamentally, the issue with criticism of post-incident debrief use is that research on it is based on generalisation from a poor evidence base. It has also been acknowledged that the studies included in the Cochrane review (Rose et al, 2002) are not relevant or applicable to emergency workers and that further research is required.

Promoting routine debriefing after both critical and non-critical incidents may assist a culture change (Gardner, 2013). If time is taken to debrief after a normal event, it is more likely to occur more naturally after critical events.

Implications for practice

Conducting a debrief provides a plethora of opportunities to enhance clinical care while simultaneously supporting staff welfare. It is the first step in the process of reflective learning that is ingrained into paramedicine and wider healthcare profession education. It has even been described as the linchpin in the process of learning (Gardner, 2013).

Change in practice cannot occur without gaining an understanding of actions and debriefing is how this can be achieved. The purpose of debriefing is not to replace individual counselling or intensive psychological interventions but to help identify individuals who may require further assistance. Showing support in the work environment can promote resilience in even the most demanding environments (Schmidt and Haglund, 2017).

While the advantages of immediate single-session or routine debriefing practice are still debated, the overall benefits of conducting debriefs are not. This contention should not be used as an excuse to abandon single-session debriefing as it suggests that doing nothing for individuals who have experienced traumatic events is acceptable (Wesseley and Deahl, 2003).

The military and aviation industries have been pioneers on the frontier of debrief practice for some time. This has allowed them to achieve high reliability organisation status. Rivera-Chiauzzi and Lee (2016) explain that they do so by implementing systems that facilitate consistent accomplishment of goals while avoiding catastrophic error, using systems built from the foundation of debriefs.

If prehospital care is to strive for the same status, practitioners must all cultivate a culture of open and honest reflection by avoiding the assignment of blame. This will only further improve patient care, safety and clinician resilience.