The concept of distance education is not new, but since its birth as radio broadcasts and correspondence courses it has undergone considerable metamorphosis. It has moved a long way from the slightly ‘second class’ reputation of some correspondence courses to being fully accepted as a vehicle for delivering world-class education, and indeed is now the teaching and learning method of choice for many people. The meaning of the term ‘distance education’ has changed somewhat over the years as delivery methods have evolved. In this article the phrase refers to all teaching that does not rely on the co-localised presence of a teacher: thus it includes the use of tailored teaching texts, broadcast media, e-learning packages delivered to a desktop computer, laptop or mobile device, and the web for both delivery of teaching and interaction with other students or teachers. These approaches may be used not just for teaching but also for assessment.

It is easy to see that a number of purely theoretical subjects can be taught at a distance without problems, but it is perhaps more difficult to understand how distance methods can be used to teach vocational, ‘hands-on’ subjects such as health care. Yet distance methods have been used successfully to educate health workers in the broadest sense for over 40 years (Dodds, 2011). As information technology has developed, there have been increasing opportunities to think innovatively about more effective ways of teaching health care workers. For example, technological solutions have been sought for disease management (Muramoto et al, 2003), and virtual reality packages have been used to train a number of healthcare professionals (Mantovani et al, 2003). Thomas and Gosling (2009) found distance methods valuable for teaching information literacy to healthcare workers. E-learning packages have been produced to develop skills in a number of areas, for example in disaster management (Atack et al, 2009) and nurse-patient relationship management (Brunero and Lamont, 2010). Evidently, for a number of reasons, there is a growing movement away from traditional classroom teaching for a wide range of health care topics.

Teaching emergency care

What about using distance teaching for emergency care? This area too is developing, and now has a small, but growing, evidence base. Stansfield and colleagues (2001) used distance teaching for medical first responders, and Conradi and colleagues (2009) used virtual simulations for teaching paramedic skills. Hubble and Richards (2006) compared the performance of paramedics trained by distance or conventional face-to-face methods, and concluded that distance teaching is effective, and in some cases a preferred method for this profession. De Lorenzo came to a similar conclusion for teaching military medical personnel (De Lorenzo, 2005). The current drive to educate more paramedics, while training budgets fail to expand in line with increasing costs, means that ambulance trusts have to seek new, cost-effective ways of delivering this training and getting more qualified paramedics on the road. Can distance education play a role in this?

High-quality distance education

The Open University (OU) is widely recognised as being the world leader in distance education. Now more than 40 years old, the OU has taught 1.8 million students, and is the UK’s largest university, with a widening participation record second to none. Importantly, it has been at or near the top in the National Student Satisfaction Survey (NSS) since this began in 2005. The secret of the OU’s success is the model it adopts for teaching, called supported open learning (SOL). SOL acts at several levels, including carefully designed teaching material with inbuilt pedagogic scaffolds, personal academic support from dedicated, specialist tutors, and above all, a focus on teaching students how to learn and organise their learning. Other higher education providers (HEIs) also offer distance learning, but judging by the NSS, none currently approaches the OU in terms of the student support and resources offered.

The OU’s teaching materials come in a variety of formats. Forty years ago the teaching was achieved by specially written texts, supported by radio and TV broadcasts (some insomniacs may still remember the late-night BBC2 OU programmes) and, for science subjects, home experiments. However, technology has allowed the development of a whole host of other resources including videos, interactive DVDs, web-delivered components, interactive forums, mobile accessibility and YouTube clips amongst others. This range of teaching methods may be complemented by face-to-face teaching carried out at tutorials, day schools and residential schools. This blended learning approach has worked well empirically, and has been confirmed by independent researchers to be an optimal approach for teaching in the health area (Lam Antoniades et al, 2009; Pearce et al, 2012). The OU’s approach to teaching vocational subjects with a substantial practical element is to use all the appropriate methodologies as listed above, but also to enter into partnerships with the relevant professional bodies and employers. This ensures that the subject material and skills taught match the needs of the employer and the wider profession.

The OU's Paramedic Sciences qualifications

The OU offers a Foundation degree (FD) and a Diploma of Higher Education (DipHE) in Paramedic Sciences for students who are already working in a relevant healthcare job, and whose employer is willing to support them in becoming registered paramedics. ‘Support’ in this instance implies active provision of equipment, including IT equipment, and opportunities to learn and be assessed on practical skills. It does not necessarily imply substantial financial support: course fees may be paid by the employer where funding is available, or may be paid by the student, for whom the prospect of career and salary advancement goes a long way to offsetting the short-term financial stringencies. Both the FD and DipHE qualifications are accredited by the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC).

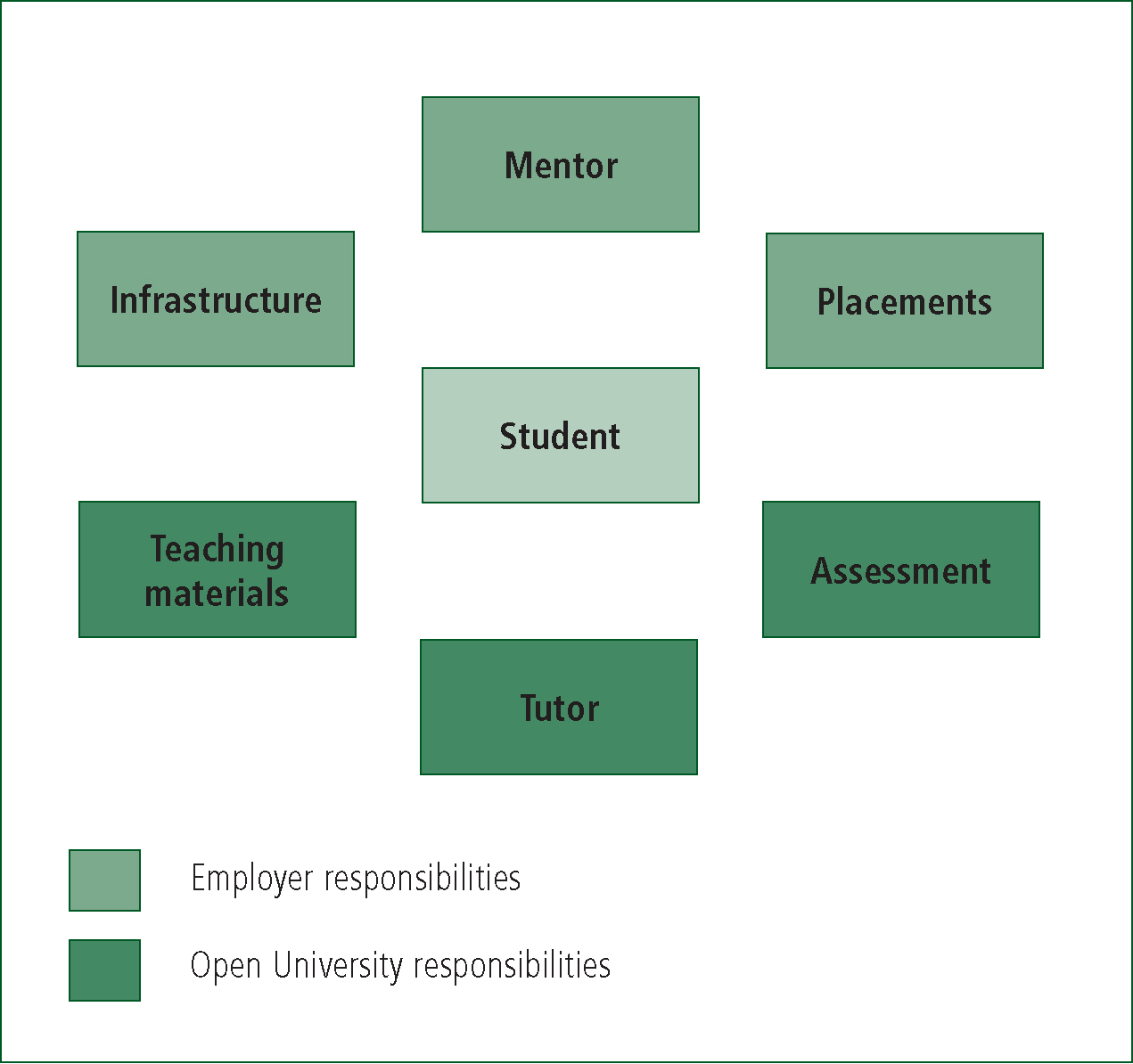

For students following these programmes of study the OU and the employer (such as an ambulance trust) enter into a collaborative agreement in which the OU remains responsible for the ‘theory’ teaching, while, as noted above, the employer supports the student in learning practical skills. Crucially, the student remains an employee throughout their studies, which are undertaken part-time and alongside the normal job. The collaborative agreement stipulates that the OU provides all the teaching materials and a tutor, and carries out the assessment. The employer provides a workplace and infrastructure that will allow the student to learn the requisite practical skills. This commitment includes organising the necessary practice placements (the range and number of placements is driven by the requirements of the College of Paramedics), and running skills labs and OSCEs where appropriate. The employer also provides the student with a workplace mentor, whose role is to teach and assess competence in the practical skills. This distribution is illustrated in Figure 1, which also shows the overriding tenet of the OU’s approach, namely to put the student at the centre of all activities.

Challenges and benefits for employers

The drawbacks and advantages of teaching biological subjects by distance education have been documented (MacQueen and Thomas, 2009). Not surprisingly, the main challenge is teaching hands-on skills that require interaction with biological material, and so have a tactile component. Even in the most technologically advanced virtual reality simulations this element cannot yet be provided. Thus the OU’s collaborative model is an ideal way to overcome this challenge: the tactile elements are provided in the real-life working environment in a safe and supervised learning context. OU student paramedics, like others, learn their skills on practice placements. The main difference between the OU approach and that of other HEIs is that, in line with the collaboration agreement, the employer organises the placements. This can be quite a challenge for the employer, particularly if student numbers are high, and in the OU’s experience lack of suitable placement experience is a major contributing factor to student failure. The problem is often exacerbated by the reluctance of organisations to offer placements, and the drive towards ever higher numbers of paramedic and other students is not likely to make this situation any easier in the near future.

Placement provision is clearly a disincentive for employers, so what are the benefits for them of the OU model? There are several, largely associated with cost, flexibility and quality.

Cost

The rising cost of higher education has made it increasingly expensive to educate paramedics. In line with its open access policy, the OU charges significantly less than most other HEIs. There are additional costs that may be incurred by the employer in the provision of skills labs and placements, but the obverse of that is that since the student remains in the workplace there are no back-fill costs or prolonged absences for ‘college days’ (or terms). Overall many employers find the OU model cost-effective.

Flexibility

The OU’s most popular delivery mode is parttime. For the paramedic qualifications the study rate is half-time over four years, although other HEIs offer alternative study patterns. The flexibility of distance learning in terms of study periods and locations means that it lends itself well to people who are also in employment; indeed more than 70% of all OU students are working alongside their studies. For health care employees who work changing shift patterns, this flexibility is ideal as it allows them to fit in their studies when it suits them and their employers, rather than having to attend face-to-face sessions which may be quite some distance away, at set times. The consequence of part-time study, of course, is that it takes longer for students to graduate, so employers need to strike a balance between short-term and long-term front-line staffing needs.

Quality

Quality is a difficult parameter to measure, yet it is all-important for commissioners of education who require reassurance about the wisdom of their spending decisions. As noted above, the OU is a leading provider of distance education both in the UK and globally (Dodds, 2011). Numerous external quality review processes confirm that the quality of teaching is very high (for example, QAA, 2009), and the National Student Satisfaction Survey (2012) results indicate that students are appreciative of the SOL model. The OU has been awarded the Skills for Health Quality Mark for the Certificate of Higher Education in Healthcare Sciences, which forms the first half of the Paramedic Qualifications. These facts all indicate a high-quality offering.

Challenges and benefits for students

Many of the benefits of distance education for employers also apply to students, such as cost (for students who are paying their own fees) and flexibility. Students are pleased to be able to earn while they learn, particularly those who are paying their own course fees. Distance education addresses particularly well the needs of adult learners, many of whom have significant lifestyle commitments, and could not easily undertake study in a conventional brick university. They are able to fit distance studying much more comfortably into their lives. They can study at times and places that suit them, and there are few ‘hard’ deadlines or requirements to attend teaching sessions. However, it is important for students to be self-disciplined and organised about their studies: ‘trying to fit it all in’ is a common cause for concern. In fact, the time management and self-motivational skills demonstrated subsequently by OU graduates are among the features most praised by employers both in the health and in other sectors. This is a benefit that few students recognise as they are undertaking their studies, but one that they universally appreciate once they have finished. Students generally need to be helped to develop these skills, and this emphasises the need to use a high-quality distance learning programme that puts the student at its core.

Challenges and benefits for HEIs

The OU is far from the only provider of distance education in the UK, and there is a wide range of delivery models that include some ‘distance’ components. Anecdotally, a number of HEIs first started offering distance education because they believed that it would allow them a higher throughput of students, and would be a cheaper delivery option than conventional face-to-face teaching. These perceived benefits have not materialised to the expected extent, the former in part due to the stringent student quotas that are imposed on HEIs, and in part because of the difficulties experienced in arranging student placements. The latter point has also proved elusive: as Dodds and others have pointed out (Dodds, 2011) the key to successful distance education is the careful construction of quality teaching materials, and the provision of excellent student support mechanisms. Both of these factors require large financial and infrastructure commitments, and good distance education is not a cheap or quick option.

There is a danger that a few ill-conceived or insufficiently funded courses that do not yield good outcomes for either employers or students could tarnish the reputation of distance education. This would be a great shame, given how successful this approach can be, and HEIs are rightly wary of the reputational damage that can ensue when students have a poor study experience.

The future for paramedic distance education

In spite of the fact that paramedic practice is quintessentially hands-on, and therefore perhaps not an obvious choice for a distancetaught subject, there are many advantages to this approach. The flexibility of distance education, even when blended with face-to-face teaching, can bring benefits to employers, students and HEIs. There is enormous potential to develop different models for delivering teaching of theoretical components at a distance, while employing more conventional face-to-face approaches to teach the tactile skills. The OU’s SOL model, outlined above, is one such successful approach, but no doubt there will be others. Much research remains to be done to identify the best blend of delivery methods for particular topics, so the current situation is likely to change as our understanding of the pedagogy becomes more sophisticated.

The likely future improvements in technology will make mobile learning more and more accessible, requiring teaching material to be tailored for a range of different delivery devices. Although this is a large task for the providers, the benefit to students, and the consequent improvement in success rates, makes it a worthwhile undertaking.

Inevitably there will be sceptics who do not agree that paramedics can be taught properly at a distance, and who will find it difficult to accept that people taught in this way can be effective in practice. Here too there is a need for evaluative research, building on the work of Hubble and Richards (2006), that can assess the level of performance achieved by students graduating from different types of course. Initial observation of OU graduates (MacQueen, unpublished observations) suggests that they are every bit as capable of delivering quality care as their more conventionally taught counterparts, though quantitative data to support this view have not yet been published.

Conclusions

The take-home message is that distance education is a valid part of a blended approach to paramedic education, and can be used to deliver highly trained and effective practitioners. It can bring benefits to employers, students and HEIs, although, as with any form of teaching, there are pitfalls that must be avoided. The main advantage of distance teaching is its flexibility, allowing students to earn while they learn, and to remain in the workforce during their studies. It is anticipated that this approach to paramedic education will become more and more widely appreciated, and will remain the method of choice for some student populations.