The free and informed consent of a potential research participant is regarded as the fundamental basis of ethical research (Declaration of Helsinki, 2013). The now well known horrible history of abuse and exploitation of vulnerable persons in research has served to emphasise the point (Beecher, 1963; Pappworth, 1967; Annas et al, 1992). However, this genuine concern for the vulnerability of those who lack the capacity to consent has created an ethical dilemma. Involving adults in research in circumstances when they lack or lose the capacity to consent has been legally problematic and remains ethically troubling. An absolute ban on the involvement of people who cannot consent may be the only effective measure to protect the vulnerable but it would have the negative consequence that important, often life-saving research for the direct benefit of those individuals could not be conducted. The effect of a ban is that those very people who would most benefit from research are unable to benefit (Chalmers, 2007). An equal and related concern has been consistently raised by researchers, namely that an overly stringent insistence upon what Roberts et al (2011) call the ‘rituals of consent’ may also be detrimental. In the recent past, researchers and Research Ethics Committees (REC) were forced to employ an ethical ‘fudge’ with regard to research involving adults who lacked capacity. In such cases either the research was justified on the basis of the ‘doctrine of necessity’ or else a ‘proxy’ consent for the incapacitated person was given by the next of kin or closest relative. However, such practices had no basis in law and left the participant, an already vulnerable person, open to further exploitation as there were no legal safeguards. These actions also left the researcher and REC open to legal challenge, since the actions violated the principles of common law and left them open to a charge of unethical practice.

There is now a legal framework which permits researchers to involve people who lack the capacity to consent. Such research must be reviewed and approved by a properly constituted REC, meet the strict criteria for justifying such research to involve adults who lack capacity (ALC) and adhere to the rigorous safeguards for the protection of research participants. With a specific focus on pre-hospital and emergency medicine research (PHER) this paper reviews the main provisions of the legislation as set out in the Mental Capacity Act (MCA 2005) and The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations (2004/1031) for involving ALC in research. The paper describes the legal framework and responsibilities of researchers and discusses some of the challenging ethical issues which inevitably arise. It is vital that researchers are familiar with the legal requirements that apply to research and are able to articulate sound reasoning with regard to the many ethical issues such research inevitably raises. This paper's particular focus is a timely consideration of the issue of conducting research that is time-critical, that is; research which must be initiated within a particular time window for it to be effective, as this is a common factor within PHER.

It must be noted that the MCA applies only to England and Wales. Scotland introduced a legislation via The Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 and Northern Ireland is currently processing its own legislation. This paper will only address the context of adults in England and Wales, though the ethical issues are common across all contexts.

Background

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) took force in 2007; the long-awaited legislation that addressed the legal lacuna regarding decisions made on behalf of adults deemed unable to consent for themselves. There was a long lead into the enactment of the MCA beginning in 1989 with the Lord Chancellor's request for the Law Commission to review the situation of adults unable to consent for themselves (Bartlett and McHale 2003). There were several subsequent reports that scoped the wide range of issues that a comprehensive legal framework would need to engage with (Law Commission, 1995;Lord Chancellor's Department, 1997). The question of whether to address the inclusion of adults lacking capacity (ALC) in health and social care research was only raised at a late stage of the process and, initially, research was not addressed in the draft Mental Incapacity Bill (House of Lords, House of Commons 2003). It was on the recommendation of the Joint Scrutiny Committee (JSC 2002–03) that the provisions for research were introduced into the legislation, recognising that not to do so would jeopardise the development of treatments for incapacitating conditions. The final version, which passed into legislation, did include provisions for research (sections 30–34, MCA 2005). It must be noted that research was not the main focus of the MCA but rather the provision of a legal framework which covered all aspects of care, treatment, and the financial affairs of adults lacking capacity (Code of Practice 2007:15). Although the research provisions constitute a short section of the MCA, they do empower the REC to approve research involving ALC and provide grounds on which researchers may justify the inclusion of ALC. A key feature of the MCA is that it is grounded on common law principles and as such it does not permit ‘proxy’ consent for adults; however, it does set out the conditions under which research involving ALC may be conducted but without consent. The MCA, read in conjunction with the Code of Practice (2007), also sets out the responsibilities of researchers when conducting research involving ALC. The MCA addresses all instances of ‘intrusive’ research involving ALC, including research conducted in the social care setting, however it explicitly excludes research that is a clinical trial of a drug or medicine. Clinical trials are governed by separate legislation, The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations (2004/1031); henceforth referred to as The Regulations. Researchers working in PHER must be familiar with common law principles, the research provisions of the MCA and, where the research involves a clinical trial, The Regulations.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 and its implications for PHER

Up to the point of the MCA coming into force in 2007, the Law was insufficient with regard to the wide range of decisions concerning adults who lack capacity for which the common law doctrine of necessity was inadequate (Bartlett and McHale, 2003). The MCA 2005 brought in a legal framework, which is now well established, and offers a mechanism for those who are caring for or treating people who lack capacity to do so lawfully, so long as they act within the framework of the MCA and accompanying Code of Practice (2007).

The MCA framework ought to be an adequate remedy for the concerns raised by critics such as Chalmers (2007) and Roberts et al (2011), as it permits a scientifically robust, ethically sound research project to be given a favourable opinion by an REC. Though critics have argued that the provisions do not go far enough.

The research provisions of the MCA and how they apply to PHER

The research provisions of the MCA 2005 are set out in sections 30–34 and make it lawful to carry out “intrusive” research involving people without the capacity to consent for themselves. “Intrusive” research refers to research for which, under common law, consent of the participant is required ([s.30(2)]). Intrusive research need not be physically invasive, and may include clinical research, access to personal data, or other forms of qualitative research, but excluding research that is classified as a clinical trial (MCA 2005 [s.30(4–5)]). There are some circumstances in which consent is not mandatory, such as research that utilises non-identifiable data, identifiable data with approval of the Health Research Authority (The Health Service [Control of Patient Information] Regulations 2002, as amended by section 117 of the Care Act, 2014). Where researchers intend to recruit ALC then (s.30[4]) requires that the research is approved by an “appropriate body”; for England this means RECs operating under the auspices of the Health Research Authority (HRA).

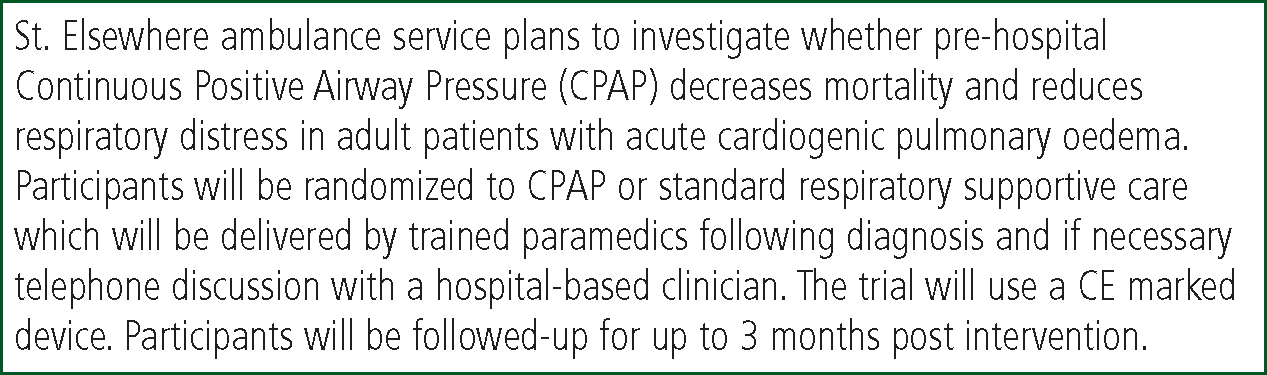

In order to explore the legal requirements and the attendant ethical issues of conducting PHER, it is useful to consider a possible (fictional) research context such as a device related study (see Fig. 1).

Prior to commencing the study, the project must have a favourable opinion from an appropriate body; a recognised REC.

All researchers seeking to conduct a study including ALC must design a methodology that is compatible with the MCA both in broad principle and with specific attention to the research provisions. The MCA is based upon five broad principles which are there to guide the actions of professionals and carers in their approach towards ALC. The principles reflect legal standards within common law and other relevant statutes such as the Human Rights Act (1998). They are also premised upon ethical approaches to the respect for persons; requiring professionals and carers to work in supportive ways to enable people to make their own decisions in as wide a sphere as possible. The principles have direct implications for researchers in terms of how they design their strategies for the inclusion, recruitment and safe-guarding of research participants. Researchers must take reasonable steps to demonstrate to the REC the ways in which the five principles have informed their research protocol. The principles will now be discussed with reference to the EMAP study.

Applying the 5 principles

The first two principles are concerned with judgments about capacity and steps to be taken to enable a person to make a decision for themselves. Principle 1 states: “People must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they lack capacity.” Principle 2 states: “Before treating people as unable to make a decision, all practicable steps to help them do so must be tried.” With regard to these principles, researchers working on the EMAP study must consider the range of circumstances in which they may encounter a potential research participant. For example, they could be responding to an emergency call to attend a patient at home and find Mr. Smith, an elderly man, alone and in acute respiratory distress.

The principle of presumption of capacity requires the researchers to recognise that a conscious person capable of communicating is likely to retain some, albeit limited, capacity for decision-making. The MCA emphasises that capacity is decision-specific, and so, researchers must respect that most people with impaired capacity will nevertheless retain decision-making powers for some aspects of their life. The key issue in these circumstances is to apply a suitable form of assessment of Mr. Smith's capacity to consent and not merely presume that he lacks capacity. The MCA guidance on this is that a person is judged to be lacking capacity if, due to “an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or the brain” (MCA 2005 [s.2(1)]) they are unable to: “understand information relevant to the decision, retain the information, use or weigh the information or communicate his decision (by any means)” (MCA 2005 [s.2(3)]) The second principle makes it a requirement to support people with relevant impairments to make their own decisions by taking all relevant steps to do so. While it may be reasonable to consider that Mr. Smith's “mind or brain” is likely to be impaired due to anoxia, anxiety or for other reasons, the researchers must nevertheless explain the purpose and relevant risks and benefits associated with the study. This can be done quickly by a verbal account of the study, though brief written details ought to be available. The details of this procedure can be agreed in advance with the REC. At the very least, alerting Mr. Smith to the potential for being entered into a study provides him with an opportunity to refuse to be in the study; a fundamental expression of his autonomy. The right to refuse, for whatever reason, is also consistent with principle 3: “People should not be treated as unable to make a decision merely because they make an unwise decision.”

As with any instance of clinical or research-related procedures, a verbal explanation ought to accompany all interventions. The MCA does not however, require a lengthy delay to initiating research or therapeutic procedures, and here, principle 4: “Acts or decisions on behalf of people who lack capacity must be in their best interests” is relevant. This can have several implications, but two are particularly significant. The first is that there must be grounds for believing that being entered into a study is not against the interests of the participant. This claim needs to be established before commencement of the study by showing, for example, that there is equipoise between the two or more potential arms of the study. The second is that any refusal to be in the study will not result in detrimental prejudice. Therefore, should Mr. Smith refuse to participate in the study, he ought to be treated according to the current standard protocol. The MCA imposes a duty on those working with adults with impaired decision-making capacity to make decisions that are compatible with their wishes, but always in their best interests (Principles [s.1(3–6)], Donnelly, 2009).

The fifth principle states: “Before any act or decision, the person responsible must consider whether the purpose could be achieved in a less restrictive way.” This is a steer to researchers to design a protocol that is the least invasive and intrusive; for example, by considering the range of personal data collected, the number of clinical procedures/assessments the subject is exposed to, and to consider ways of minimising research procedures.

The requirements for a favourable opinion from an REC

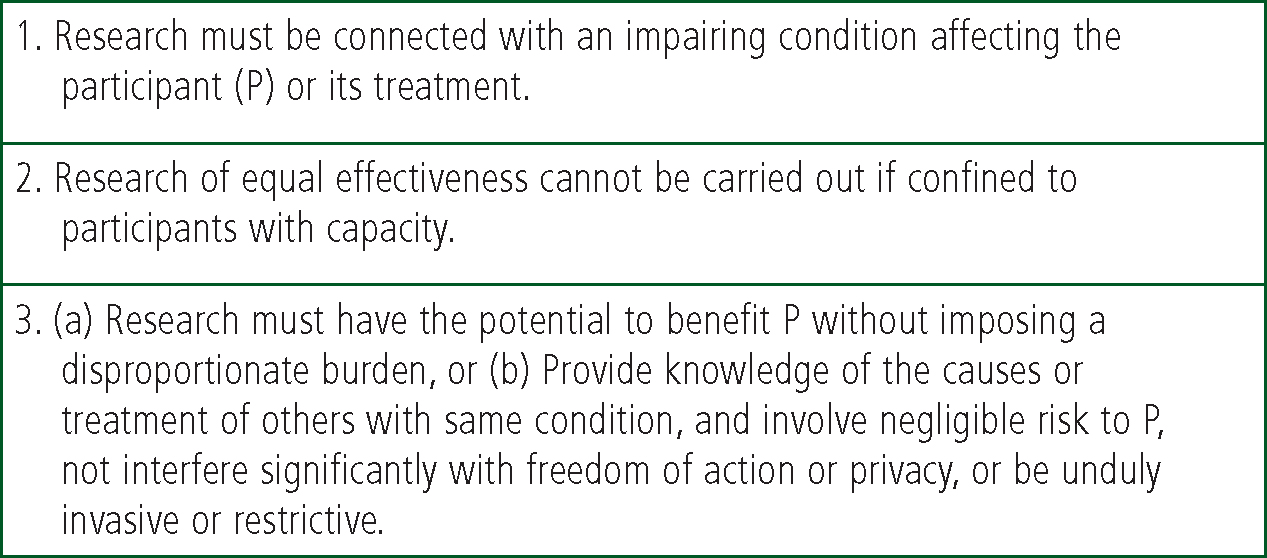

Before any participant can be recruited, EMAP must have a favourable opinion from an REC. The criteria used by the REC are set out in s.31 of the MCA as summarised in Fig. 2. When applying to an REC, the researcher will be asked to indicate their intention to include ALC. Selecting the appropriate response on the Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) application form will populate the form with questions related to s.31.

With regard to criterion 1 the researchers must demonstrate that the focus of the research is relevant to an impairing condition or its treatment and so must provide evidence, for example in the context of EMAP, that breathing problems related to cardiac failure are likely to impair brain function and thinking due to anoxia. The research must also meet criterion 2 and show that it is necessary, and not merely convenient or desirable to include ALC in order to conduct the research. The proposed research should have the potential to be of benefit to the participant, or those with a similar condition, involve negligible risk and “not interfere significantly with freedom of action or privacy, or be unduly invasive or restrictive” [s31(6)]; a criterion which echoes principle 5. Although the MCA cannot provide detailed guidance on how to interpret the requirements, the onus is on the researchers to provide for the REC a well reasoned case supported by evidence.

Safeguards for the participant who lacks capacity

For some, the decision to provide a lawful basis for the inclusion of adults unable to consent for themselves is crossing a moral line. However, the MCA, together with the Code of Conduct (2007), detail a number of important safeguards. One of these is the requirement to consult others (s.32) to ensure that any decision to include an ALC is not against their interests. Therefore, researchers must seek advice from a person (a “consultee” [MCA s.32(2-3)]) who knows the candidate participant, and is concerned for their welfare (see also Department of Health and Welsh Assembly Government, 2007). The researcher must inform the consultee that their role is to advise the researcher as to whether recruiting the person concerned is consistent with what the participant would likely choose for him or herself if they had the capacity to do so (MCA [s.32(4)]). Several commentators regard such “substituted judgment” approaches with some scepticism and see them as highly vulnerable to abuse (Buchanan et al 1990; Torke et al, 2008). There are certainly several foreseeable problems with substituted judgment approaches; for example, can the researcher be sure that the consultee's advice does reflect the wishes and values of the participant? Can the researcher judge whether the opinions expressed are those of the consultee or the patient? A further potential problem is for both the researcher and/or the consultee to confuse the process of consent with the process of consultation. It must be clear to both parties that when an adult, and for the MCA this includes those who are 16 years and older, lacks the capacity to consent, no other person can consent for them. Though the MCA empowers researchers to recruit without consent it must be under conditions of strict adherence to the legal safeguards and in accordance with any conditions set out by the REC. However it is likely that a person willing to act as a consultee will be concerned for the welfare and interests of the person who is unable to consent. In addition, and independent of the advice offered by the consultee, the researcher must monitor the status of the participant and not hesitate to withdraw them from the study should they give any indication that they are distressed by the research procedures or express a wish to be withdrawn. The diligent use of the consultee procedures combined with the other safeguards the MCA requires means that important research for the benefit of people with impairing conditions can be conducted lawfully and ethically (Johansson and Broström 2014).

A research participant who loses capacity during a research project must be immediately withdrawn from the study unless the project has a favourable REC opinion under the MCA. The loss of capacity requires the initiation of consultee procedures.

Emergency research

Within the context of the fictional EMAP study what is permissible if Mr. Smith is judged to lack the capacity to consent for the study and there is no potential consultee available? The MCA Section 32(9) would allow Mr. Smith to be entered into the study either with the agreement of a doctor who is independent of the study or in accordance with a procedure agreed with the REC in advance. The advice of a consultee on whether Mr. Smith should continue in the study should be sought as soon as possible.

A real and much more challenging example of emergency research procedures is illustrated by the Airways2 study. Airways2 is a randomised controlled trial of two airway devices, a supraglottic airway device versus tracheal intubation, applied in the context of out of hospital cardiac arrest. The nature of the research is such that any potential participant in need of airway support would be in no condition to consent to participate in the study. The initial research intervention, airway support with one or other of the devices, is both time-critical and of the utmost urgency and clearly qualifies as “emergency research”. Since the researchers will also be the treating clinicians at the scene, and will have a duty of care to treat their patient in a timely and efficient manner, there is unlikely to be an opportunity to consult others even if a competent consultee could be identified under such fraught conditions. Surviving participants will be followed up for a period of six months. As the protocol describes (Benger, 2015), participants who recover capacity will be invited to consent to their continued involvement with the study, which is consistent with MCA s.32(9). For participants who do not recover capacity, consultee procedures will be initiated in accordance with the MCA. This study is one of the few examples of intrusive and invasive research carried out without consent but entirely lawfully within the provision of MCA. Since there is no provision for post hoc (after the event) consent. The consent of the recovered participant can only be for his or her ongoing involvement in the research. Prior to the enactment of the MCA there was no lawful way in which a randomised study of this kind could take place.

MCA in summary

PHER that is not a clinical trial of a drug but is intrusive in the sense defined above will fall within the remit of the MCA. In the design of such a project the researcher must consider whether it is necessary to include adults who lack capacity to consent, provide for those who can consent for themselves to do so, and have appropriate procedures in place for consulting others with regard to those who cannot consent. In some instances procedures for the recruitment of participants without consent and without the use of a consultee may be justified under emergency procedures that have the prior agreement of a REC. Some studies may need to employ all three methods as parallel recruitment strategies because the legal requirement to presume capacity or consult others must be respected in the relevant circumstances.

Clinical trials in PHER

The Regulations give legal force to two EU Directives, EU Clinical Trials Directive and the Good Clinical Practice Directive (2001/20/EC). The Regulations make informed consent a condition of participation in a clinical trial, but in contrast to the MCA and common law approaches, they also allow that a legal representative can represent a person who lacks capacity. A legal representative may be a relative or close friend, or a doctor who is independent of the study. The trial must also relate directly to the patient's condition and there must be grounds to expect that the participant will benefit from the study with no or negligible risk (The Regulations: Schedule 1 Part 4.) However, even though The Regulations allow for proxy consent by a legal representative, the law is still regarded by some as restrictive, especially with regard to research that can only be conducted in urgent circumstances, is time-critical and potentially life-saving (Roberts et al, 2003; Stobbart et al, 2006). The Thrombolysis in Cardiac Arrest (TROICA) study by Spöhr et al (2005) is a randomised trial of thrombolysis therapy in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a pioneering example of research in which the importance of waiving consent to allow “emergency” research was strongly demonstrated. Even though the results were negative for the intervention, the project has become a classic example of the importance of such studies, as did the CRASH trial (corticosteroid randomisation after significant head injury) (2005) which demonstrated the detrimental effects of the current clinical standard of administration of steroids for acute head injury.

The subsequent amendment to The Regulations (2006/2984) set out conditions in which adults who lacked capacity might be admitted into an emergency trial of a medicinal product without their consent. Though the amendment has been widely supported by the research community it has proven controversial and, as Pattinson (2012) points out, the EU Directive on which the amendment is based does not contain an explicit waiver of consent for emergency research. The European Commission's draft Regulation (2012) is likely to resolve this issue once it comes into force in 2016 but in the meantime the anomaly remains. The PARAMEDIC2 trial is a current double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial of the use of adrenaline in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. The trial is justified on the basis that there is equipoise, because it is not possible to state based on current levels of knowledge, whether the administration of adrenalin in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is a benefit to patients or not. The trial has proved controversial for a number of reasons including the fact that participants will not be informed of their participation; a key requirement within the EU Directive. Critics of this approach like Stirton and Stirton (2014) have argued that a scientifically weaker design is ethically preferable than a placebo study without informed consent; though this remains a highly contested point. Despite the controversy the trial is currently running and has a favourable opinion from an REC in which the conditions for emergency recruitment without consent have been agreed. Consent to be continued in the study beyond the initial intervention must be obtained from the participant or their legal representative as soon as possible after their involvement in the study.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the person who is incapacitated and unable to consent for themselves is in a very vulnerable position. They are potentially even more vulnerable in the medical research context. Researchers have a duty of care not to create or exploit such potential vulnerability, to always act in the patient's best interests using research methods that are of negligible risk or no risk at all. Not to do so is regarded as unethical and may also be unlawful. It can also be argued that not conducting research involving those who cannot consent, when there is no other means of gaining knowledge to benefit such persons, is equally unethical. Conducting research in the pre-hospital and emergency setting is additionally challenging because the safeguards offered through consulting with, or gaining the consent of, those who know, and are close to, the patient is often difficult or impossible. The MCA and amendments to The Regulations allow adults who cannot consent for themselves to be entered into research under strict legal procedures which include a number of important safeguards. The decade since the legislation has been active has been a steep learning-curve for researchers and REC members (Dixon-Woods and Angell 2009) and there are, no doubt, lessons still to be learnt.

In addition to providing an overview of the legislation relevant to PHER, this paper has also provided guidance for researchers who are planning or are actively engaged in PHER. When seeking a favourable ethicalopinion to conduct research involving ALC, the onus is upon the researchers not only to know and understand the legal requirements that apply, but to implement these requirements through a highly ethical lens. The safety and best interests of the research participant who is unable to consent ought to be paramount. The involvement of adults who lack capacity in intrusive research or clinical trials should be recognised as ethically challenging and researchers should not only act lawfully, but subject their own practices to critical ethical scrutiny.