The concept of mass-gathering medicine originated from the need for organised medical care when a large number of people gather in one place (Leonard, 1996). Mass-gathering medicine explores the health effects and risks that can arise in such settings, as well as strategies that contribute positively to effective health services delivery during these events (Arbon, 2007).

The niche for this field of health care arose from the fact that mass-gathering events have been shown to generate a higher incidence of injury and illness than would be otherwise anticipated, considering the implication of it being a collection of ‘well people’ (Franaszek, 1986; Thompson et al, 1991; Parrillo and Stearns, 2001). The presence of an on-site physician enhances overall care, reduces liability and allows safe disposition of certain patients back to the event without transport to a local medical facility (Boyle et al, 1993).

Mass gatherings commonly include social, sporting and large-scale religious events. The Muslim Hajj pilgrimage has been given much attention in medical literature due to the emergence of Middle East respiratory syndrome (Memish et al, 2009).

Experience gained from the Athens Olympic Games in 2004 led to a collaborative effort with the World Health Organization, who support member states in hosting mass gatherings, to produce a booklet: Mass Gathering and Public Health, which reflected on lessons learnt from Athens for future events (Tsouros and Efstathiou, 2007). As per this publication, provisions required for the mass-gathering setting include necessary equipment, infrastructure and organisation in place to deliver such care, which must be considered on an event-specific basis. While producing one unifying guideline for all types of events may be too logistically complex, key themes must be considered at all events. One guideline expressed the requirements of public health providers to include:

‘Protecting the health and wellbeing of the participants and spectators from infection and intentional injuries related to improper food, water, waste, land and road traffic management’

Possible requirements and care delivery considerations that the medical division need to encompass are shown in Table 1 (Northwest Community EMS System, 2001).

| Preparatory requirements | Care delivery considerations |

|---|---|

| Meet or exceed local/regional and/or state relevant guidelines and demands. | To deliver appropriate care at fixed treatment facilities. |

| Provide appropriate cover based on medical reconnaissance (including crowd demographics, expected weather conditions etc.), statistical estimates, and experience from previous events. | To provide coverage that will guarantee rapid response for life-threatening medical emergencies. |

| Outline equipment and treatments needed based on the above. | A reliable communication method between medical personnel and with medical supervisors. |

While these considerations may vary between events, it highlights the magnitude of foresight required for successful medical coverage and the importance of planning in advance. Despite logistics being organised well in advance, preparations for the planned annual gathering of the Ahmadiyya Association, analysed in this study, actively start 6 months before the event. During this time, medical team pre-planning occured in relation to the establishment of medical first aid facilities. An analysis of previous year's medical managements are also utilised during the pre-planning phase.

Study aims

There is an increasing demand for better knowledge and understanding of medical care at mass-gathering events (Turris et al, 2014). This study attemped to identify the characteristics of a mass gathering from a medical care perspective.

The primary aims of this study were:

This study also considered the variables deemed most likely to effect the medical management of mass gatherings, as well as the variables that impact on workload across emergency services. These are important in determining resource allocations that can adequately meet the day to day demands of the emergency services.

Medical considerations at mass gatherings

Mass gatherings increase the demand on the existing medical services. Thus, effective medical care within an event will reduce the additional burden on existing services (Hodgetts and Cooke, 1999). It must not be forgotten that medical teams need to be aware of community-disease outbreaks in the locality of the event, which can adversely affect the event, or vice versa.

There are a number of differing views regarding the definition of mass gatherings. What remains consistent is that these events are usually planned and organised in advance (Zeitz et al, 2007), which could be a one-off or recurring event at the same or different locations.

Various authors have tried to define mass gatherings by attendees. Proposed attendance numbers range from 1 000 (De Lorenzo, 1997) to 25 000 people (Milsten et al, 2003), gathered together at a specific location for a defined period of time. An alternate definition is proposed by (Arbon, 2004):

‘A mass gathering is a situation or event during which crowds gather and there is a potential for delayed response to emergencies because of limited access or other features of the environment or location.’

Workload at mass gatherings has traditionally been measured in terms of service usage rate, based on the number of people treated and the number of people attending (Zeitz et al, 2007). There is a broad range of patient presentation rates (PPR) for mass gatherings, due to the diverse nature and location of events, with PPR ranging from 0.14–90/1000 (Milsten et al, 2002).

The following is a summary of determinants to the workload for a medical service at mass gatherings (Shelton et al, 1997; Milsten et al, 2002; Zeitz et al, 2007):

The medical services need to be considerate of such variables in their event and prepare accordingly.

Setting

This retrospective study analysed medical care at a planned annual mass gathering event in Alton, Hampshire, UK. The results from this study can be seen as beneficial for the understanding of risk management and consideration for the future planning of events including staffing, equipment and medicine requirements.

The annual event analysed in this study is run by the Ahmadiyya Association, a religious organisation established in the UK in 1912, which forms part of the global Islamic Ahmadiya movement. The Ahmadiyya Association have a formal annual gathering (called Jalsa Salana), where esteemed members of the community and dignitaries are invited to give speeches along with many other facilities' exhibitions, shops and dinner halls for attendees to use outside the session times. In accordance to Islamic tradition, guests are invited to learn about the Association, whose belief is based on the coming of the Promised Messiah and Mahdi of the latter days in the form of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908) of Qadian, India. The event spans 3 days, with the programme officially starting on Friday afternoon, although guests begin to gather from late Thursday morning. The event is free to attend.

Methods

A retrospective observational analysis was carried out of women and children attending the designated first aid area of the annual international Jalsa Salana convention organised by the Ahmadiyya Muslim Association. The 3-day event, which offered on-site accommodation, took place at Alton, Hampshire. Data were collected using information from completed patient report forms (PRF), completed by the medical care team of each patient, and analysis on event attendance.

The data from the medical services at this event was analysed for the years 2011–2013, inclusive. The analysis specifically examined statistics relating to the attendance of the women and children because this is a segregated event, with women presenting to the women first aid team and men presenting to the men's team.

The necessary documentation was available from the head of the medical services for the years 2011–2013. Dr Amtul Salam Sami was head of female services, with Mr Syed Muzaffer Ahmad overall lead of first aid services for the event. The data were kept securely and in strict confidence ensuring patient data privacy. As the analysis was a retrospective observational study and there was no breach of privacy or anonymity, ethical approval was not needed (NHS Health Research Authority, 2015).

The first aid care was provided by a main first aid marquee with smaller outposts at different locations on the event site, listed as below:

There was also a night team cover and 24-hour on-site ambulance.

The main first aid marquee was located in a prominent area in the event arena and was well signposted. While it was a temporary marquee, it still had the necessary basic amenities (wooden floor, chairs, tables, storage space, examination couch, ample space with a waiting area for patients). The smaller outposts had similar facilities but on a smaller scale. There was transport provision between first aid sites.

The team of volunteers working at these sites included doctors from multiple specialities (including but not limited to general practitioners, ophthalmologist, ear nose and throat specialist, allergist, acute medicine, psychiatrist, dentist, cardiologist, paediatricians), medical students, nursing staff, trained and accredited first aiders and helpers. These staff were provided with protocols for emergency procedures beforehand, and briefed before the event regarding the running of services and their responsibilities. Requirements for patients with special needs were considered, including storage of medication in a fridge.

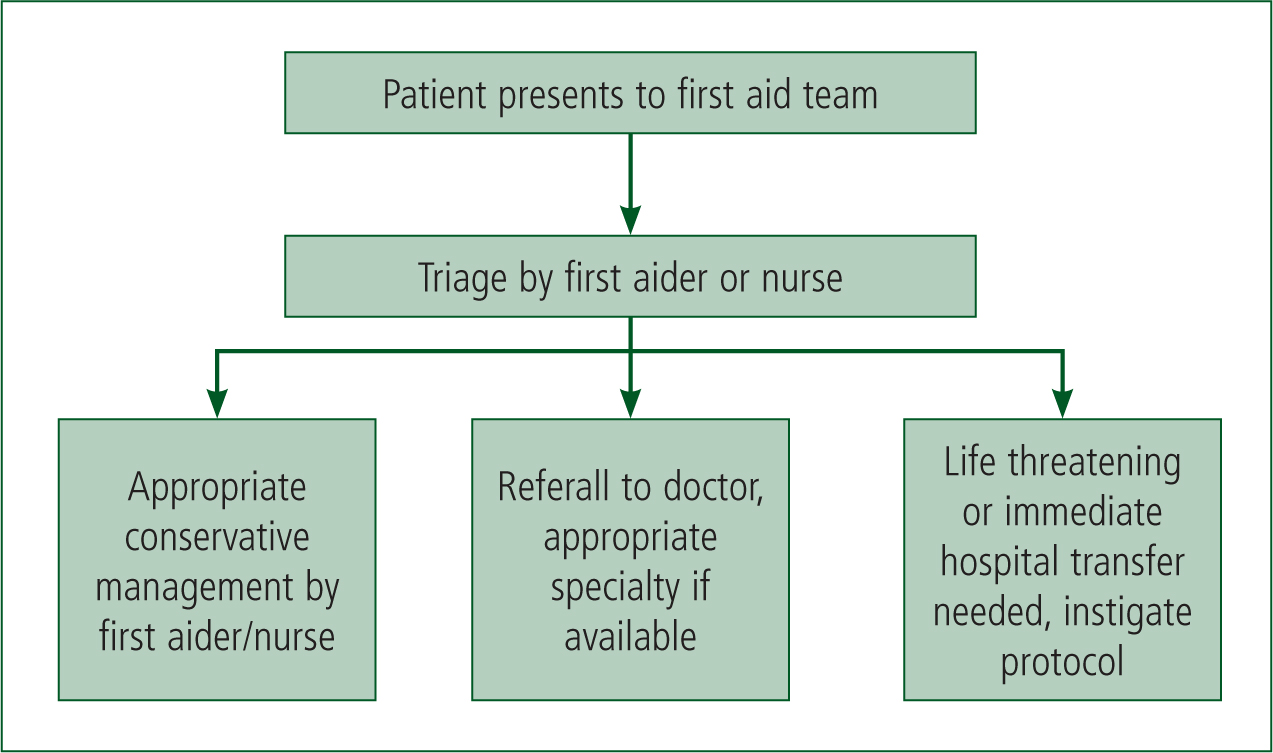

When a patient presented to any of the first aid sites, a first aider or nurse would triage the patient first and document the visit on a PRF, one for each visit. This was followed by appropriate referral (Figure 1). Note that in the multidisciplinary team there were doctors from multiple specialities. All management, whether it was conservative, referral to hospital or discharge from care, was documented on the PRF which, when complete, was kept securely in the allocated box. For any patients referred to hospital, the referring doctor was required to remain abreast of the situation until discharge. This was consistent with previously published recommendations (Northwest Community EMS System, 2001).

There were good communication links between senior members of the team. The head of the men and women's first aid team had radio contact. Landline communication was available in the main first aid tent, and mobile communication was available to contact outpost teams. Communication between medical team members has been shown to be integral to a effectively functioning team (Northwest Community EMS System, 2001).

The availability of medications was based on previous experience and forward planning. Consideration was given to commonly presenting illnesses, with medication including analgesics, anti-diarrhoeals, and treatment for bee and wasp stings. These were available to physicians only on request and documented in the PRF. First aid boxes were provided to those who had stalls set up at the event and in the dinner halls in case of an emergency, with a brief to seek medical attention, if relevant.

Results

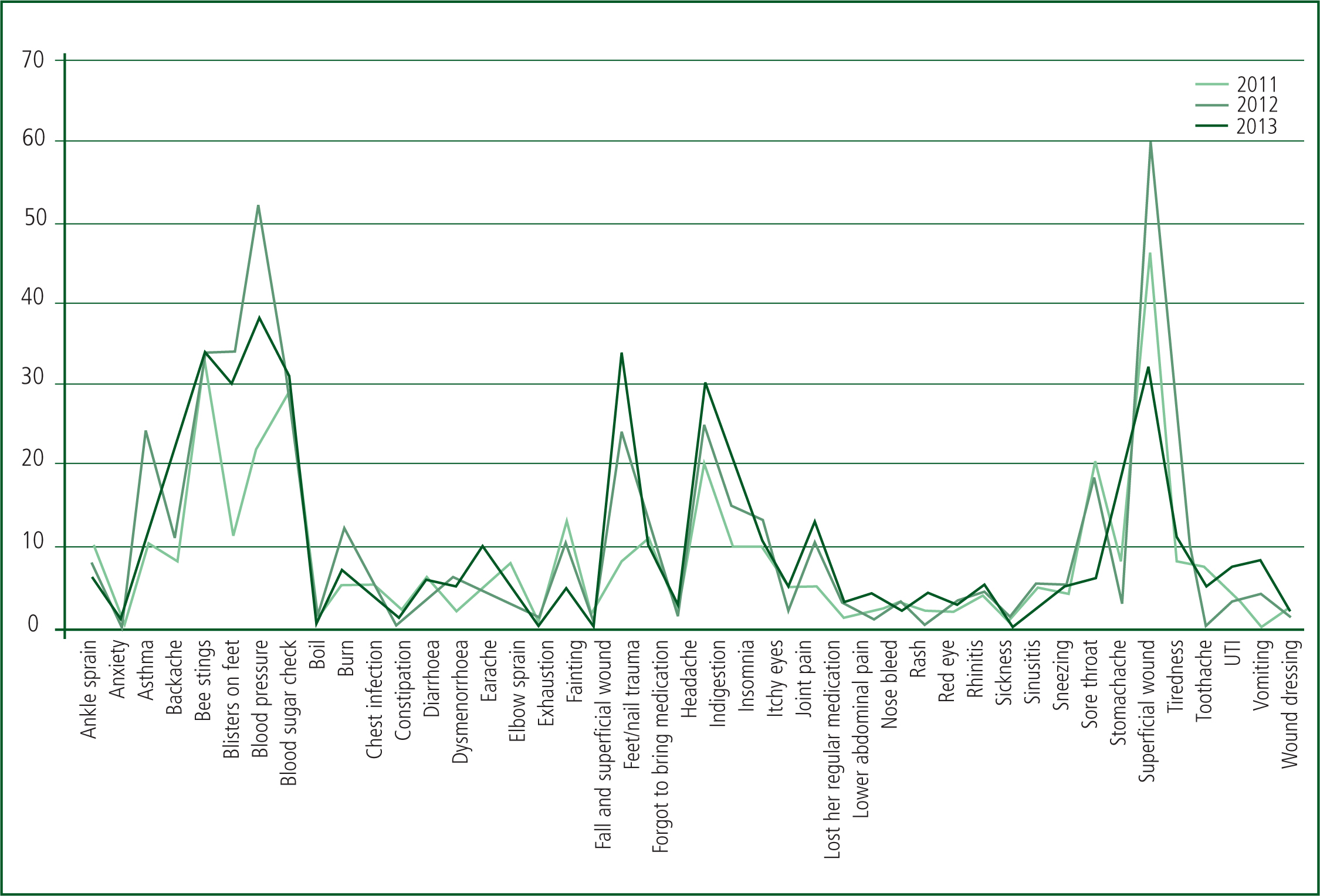

The total attendance, including men, women and children <18 years, ranged from 29 000–31 000 in the years 2011–2013. The attendance excluding men was 17 000, 18 200 and 18 234 in 2011, 2012 and 2013, respectively. Results of patients attending first aid medical care (excluding males) are shown in Table 2 and 3, and Figures 2–6.

| Illness presenting to first aid | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ankle sprain | 10 | 8 | 6 |

| Anxiety | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Asthma | 10 | 24 | 8 |

| Backache | 8 | 11 | 18 |

| Bee stings | 32 | 33 | 34 |

| Blisters on the feet | 11 | 34 | 30 |

| Blood pressure check | 29 | 30 | 31 |

| Boil | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Burn | 5 | 12 | 7 |

| Chest infection | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| Chest pain | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Constipation | 6 | 3 | 6 |

| Diarrhoea | 2 | 6 | 5 |

| Dysmenorrhoea | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Earache | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Elbow sprain | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Exhaustion | 13 | 10 | 5 |

| Fainting | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fall and superficial wound | 8 | 24 | 34 |

| Foot, nail trauma | 11 | 12 | 10 |

| Forgot to bring the medication | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Headache | 20 | 25 | 30 |

| Indigestion | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| Insomnia | 10 | 13 | 11 |

| Itchy eyes | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Joint pain | 5 | 10 | 13 |

| Lost regular medication | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Lower abdominal pain | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Nose bleed | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Rash | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Red eye | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Refer to hospital | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Rhinitis | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Sickness | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sinusitis | 5 | 5 | 3 |

| Sneezing | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Sore throat | 20 | 18 | 6 |

| Stomachache | 8 | 3 | 15 |

| Superficial wound | 46 | 60 | 32 |

| Tiredness | 8 | 18 | 11 |

| Toothache | 7 | 0 | 5 |

| Urinary tract infection | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Vomiting | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| Wound dressing | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Statistics | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total attendance at event (excluding males) | 17 000 | 18 200 | 18 234 |

| Number of patients seen | 350 | 456 | 445 |

| Percentage of total attendees (excluding males) that needed first aid attention | 2% | 3% | 2% |

| Percentage of patients seen that were children (<18 years) | 17% | 11% | 7% |

| Number of patients that were referred to hospital | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Patient presentation rate (n/10 000) | 206 | 252 | 244 |

In 2011, there were 350 patients, 17% of these were children (Table 3). Two patients were referred to hospital, one with suspected myocardial infarction and the other with an ankle injury. The fewest number of patients with chronic conditions, defined as patients suffering from asthma, hypertension and/or diabetes mellitus, were recorded in 2011, with just 17% of all patients seen suffering from such a chronic condition (Table 4).

| Chronic condition | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients seen | 350 | 456 | 445 |

| Total number of patients seen with a chronic condition (asthma, hypertension, deabetes mellitus) | 61 | 106 | 159 |

| Percentage with a chronic condition | 17% | 23% | 36% |

In 2012, there were 456 patients, of which 11% were children. Of those who attended, over one in five had a chronic condition, defined as suffering from any of the three conditions identified above. Three patients were referred to hospital, one with asthma, one with a severe shoulder sprain and one with suspected myocardial infarction.

In 2013, there were 445 patients, 7% of them children. Of those attended, over a third had one or more chronic condition. A total of three patients were referred to the hospital, two children with acute asthma and one woman with an acute abdomen.

The patient presentation rate is the number of patients seen per 10 000 attendees (Table 3). The highest patient presentation rate was in 2012 and the lowest in 2011. It is interesting to note that the hospital referral remained consistent over both years.

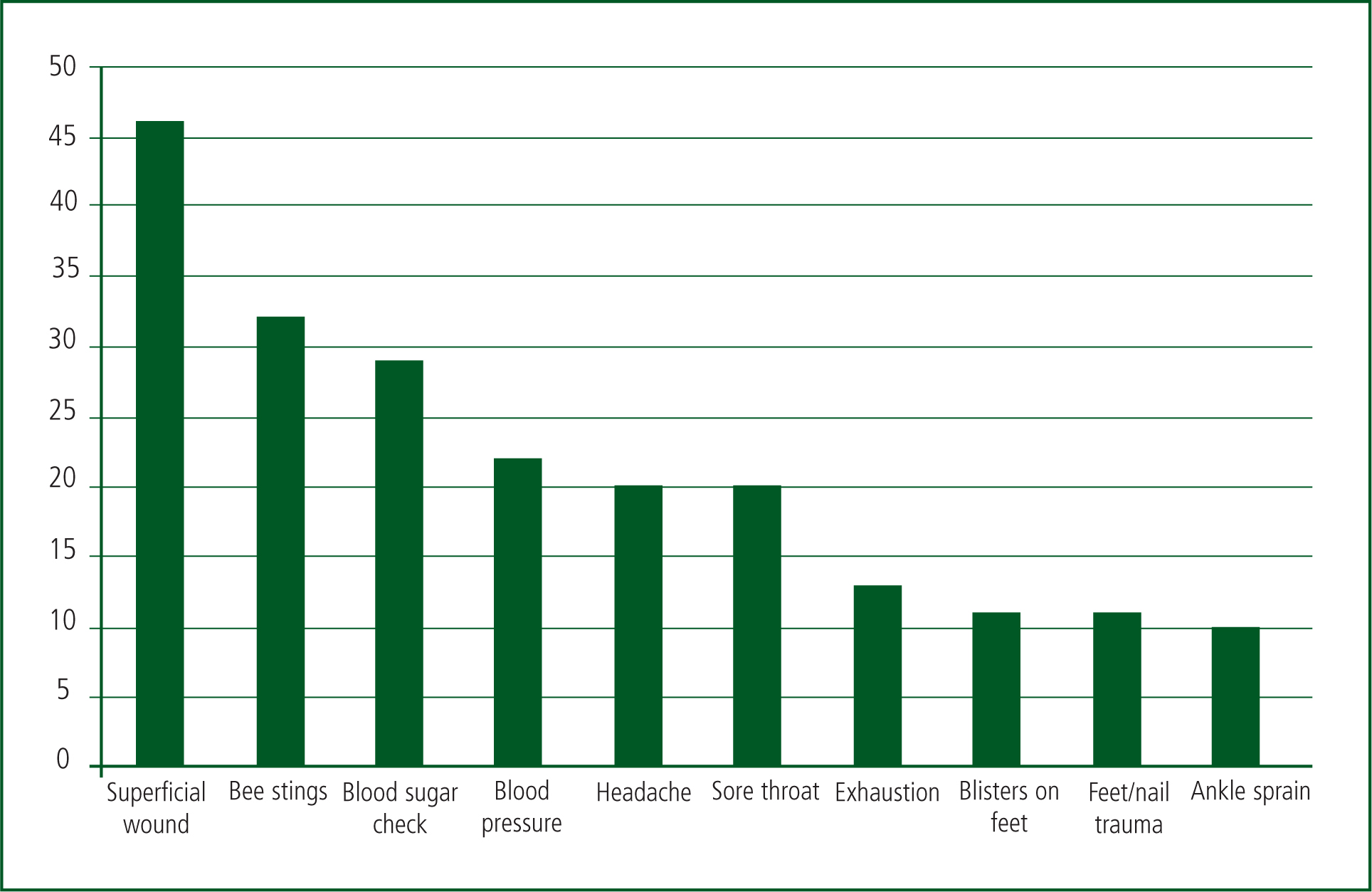

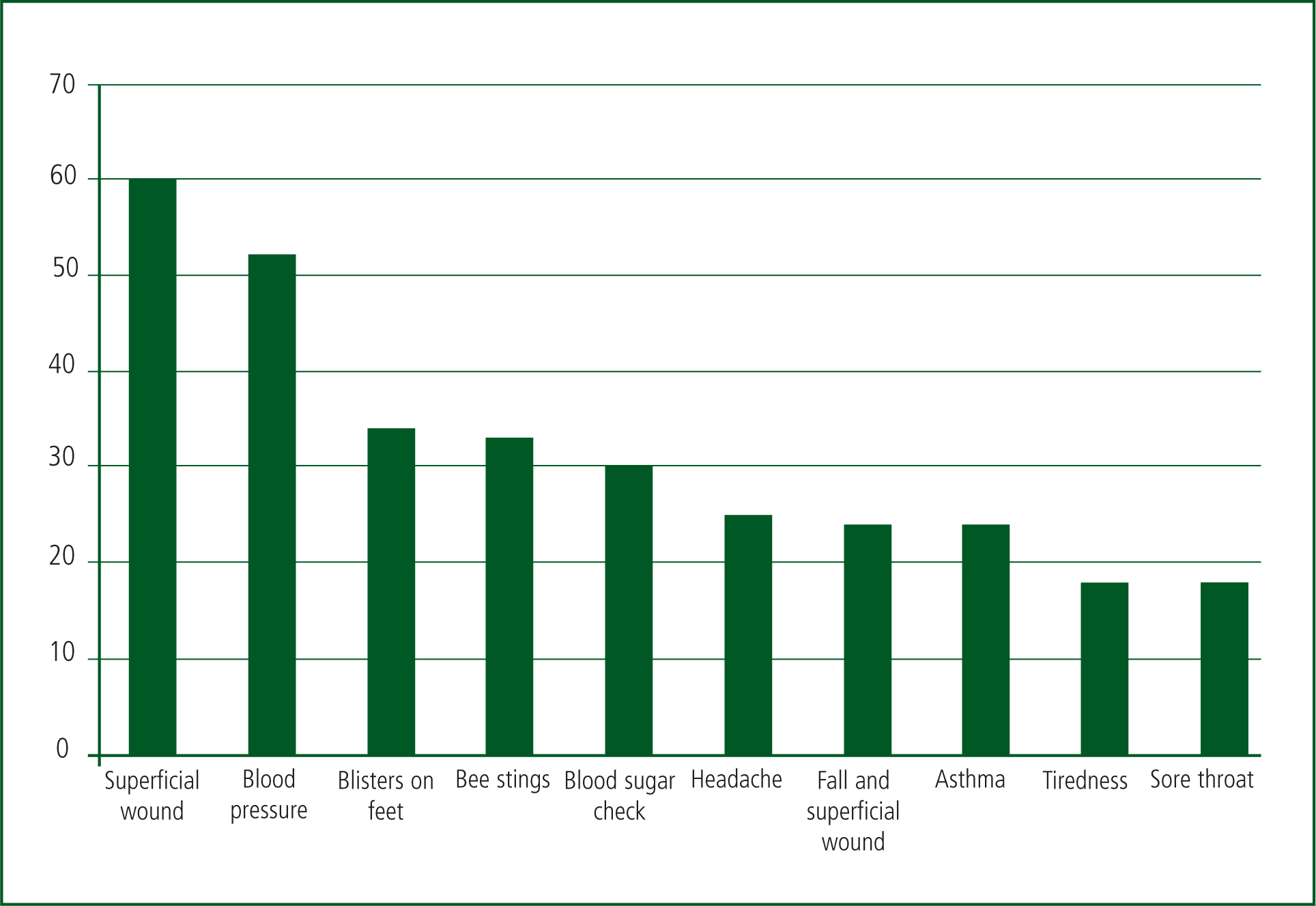

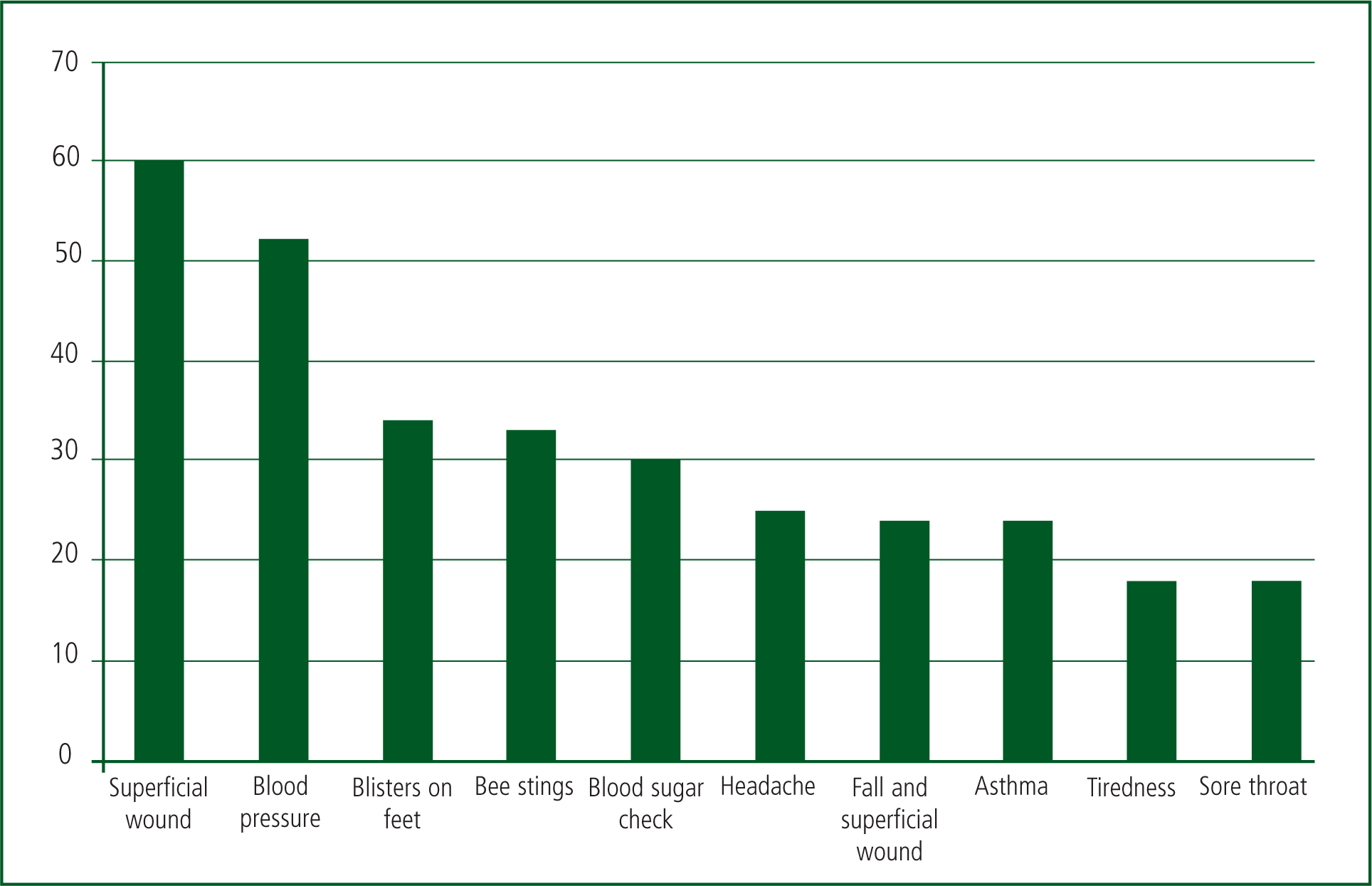

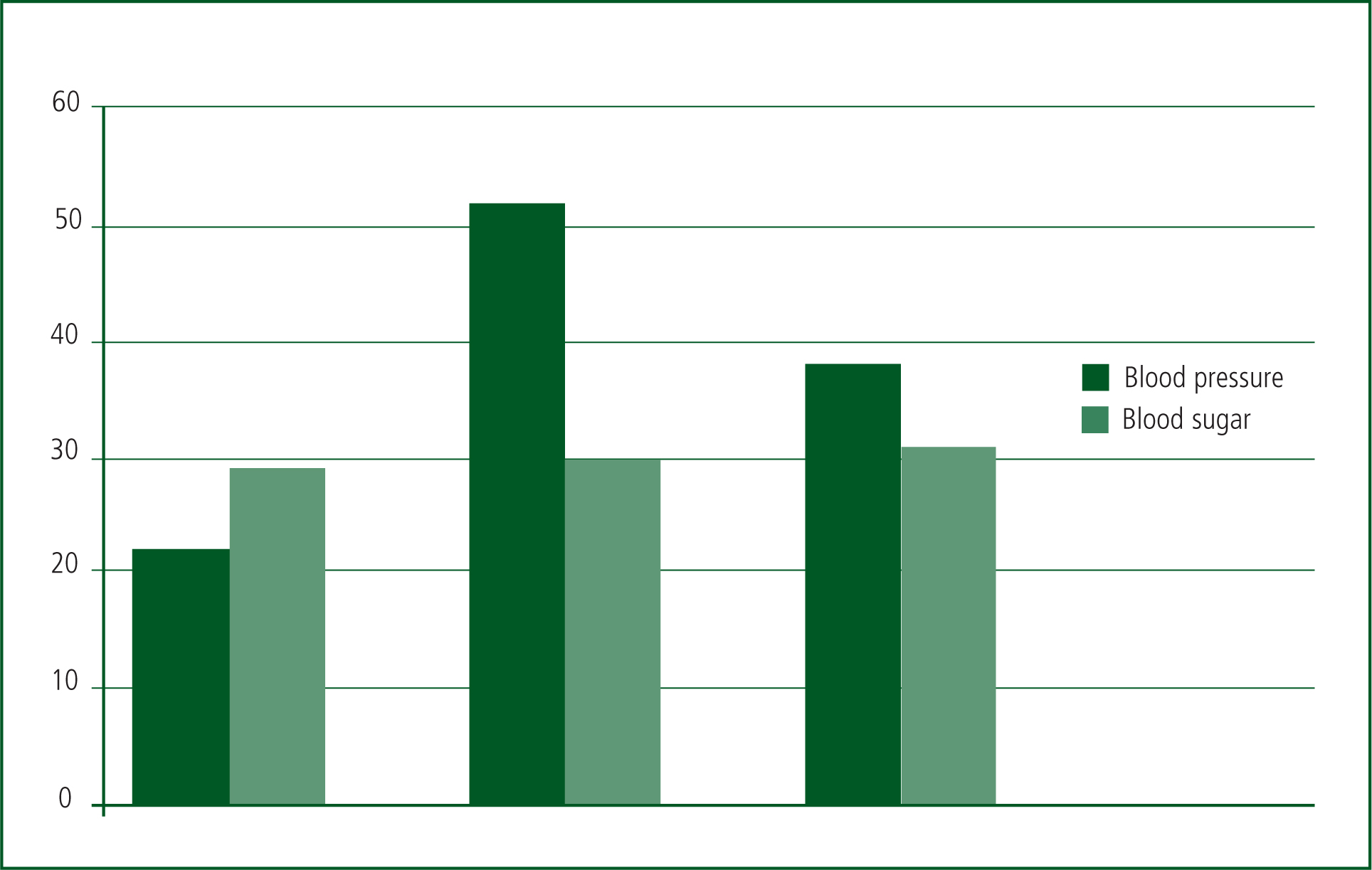

The most common conditions seen in each year have been identified and are graphically shown in Figures 2–4. Conditions related to hypertension and diabetes, even simply checking either one, made a significant bulk of the work seen, represented in Figure 5.

The results showed that the contributing factors to a patient's presentation were related to multiple factors including: the hot weather; lack of fluid intake; excessive physical activity/exertion/overwork; cold nights, which was potentially troublesome for the asthmatics; insufficient heating arrangement and patient co-morbidities.

The patient's age range spanned from just a few months to the oldest female being 88 years old. Some patients presented with more than one problem, which explains why there is a slight discrepancy between the total number of first aid attendees and conditions presented. Patients who came for a follow up during the mass gathering with the same condition are not included in this data.

A detailed analysis of male patients seen at this event goes beyond the remit of this paper. To better contextualise the patient cohort seen, the following breakdown was received: the total number of patients seen by the male team was 800 patients in 2011 and 2012, with 1 100 patients seen in 2013.

Overall, the weather for 2011–2013 was largely consistent during the day (approximately 18–23°C) with cold nights.

Discussion

The key purposes of mass gathering medical services at an event are rapid access to the injured and ill patient and effectively stabilising and transporting injured or ill patients and on-site care for minor injuries and illnesses (De Lorenzo, 1997). Numerous factors have been shown to influence the patient presentation rate at mass gathering events (Leonard et al, 1990), and certainly the contributing factors to the presenting complaints that were observed are consistent with this.

The results from the retrospective observational analysis of the Ahmadiyya Association annual gathering showed that it is a well-attended event with a year on year increase in the number of attendees. Each year the number of children being seen by the first aid team is decreasing, a wide age range is also seen by this team. It is interesting to note that the highest patient presentation rate was in 2012. This may be due to the conditions that year. In 2012, the most prevalent presenting condition was superficial wounds, both absolutely and proportionally more so than in 2011. However, as stated, no one factor can be implicated in these trends. It has been consistently seen that superficial injuries are in the top five each year, highlighting a problem that needs to be addressed.

It is also important to note that bee stings have consistently been in the top five conditions seen; they were the third most common reason for patients' presentation to first aid in 2013, and fourth and second in 2012 and 2011, respectively. Considering that bee stings also have the ability to cause an anaphylactic reaction, subsequent prophylactic measures including raising awareness and greater availability of treatment is warranted. While rash/allergic reaction is relatively low on lists of presenting conditions, it still deserves special attention at mass gathering events for this reason. However, there are several categories which were not included in the top 10 reasons to be seen by a physician, indicating that medical supplies must not be limited to the few most common conditions seen.

There was a significant burden of chronic conditions and co-morbidities, which appeared to increase with consecutive years, and possibly reflects the demographic cohort nationally as well. However, it is satisfying to know that hospital referral rates are consistent even though, each year, more patients are seen by the first aid team. This study has established a comprehensive database of information for medical management of mass gathering events. All the information gathered is first hand from the first aid team, which consisted of medical professionals from multiple disciplines.

The number of medical staff on duty needed for the event is considered beforehand, as number of attendees, according to the results, increases each year. The weather forecast for the timing of the event is taken beforehand and appropriate measures are taken.

The first aid department remains in contact with health and safety, hygiene, food and water supply and the communication department. These are the basic departments for the arrangement of a mass gathering.

There have been several attempts to describe the types of patients that present at mass gatherings, but these studies are limited to single day events (Northwest Community EMS System, 2001; Tsouros and Efstathiou, 2007). Presented here are data over multiple years on the patients presenting to first aid at the Ahmadiyya Association annual 3-day event, providing a wealth of first-hand data and experience.

The purpose of this retrospective analysis study is to ensure that the delivery of medical care is constantly improving through the analysis of the medical sector performance. Basic facts and figures concerning the delivery of medical care and patient volume are recorded and used for appropriate analysis (Northwest Community EMS System, 2001). This research measures mass-gathering medical services workloads, in the context of a large-scale religious event, and identifies factors that contribute to the workload in serving the general public.

Limitations of this study

This study only looked at one type of event, that being a religious event, where the use of drugs and alcohol was prohibited. This is not the case in some social events including concerts. This discrepancy makes it difficult to draw assumptions for future planning of such social events using our data.

This study involves women and children only. Though unique in itself, the collected data were limited by this. While raw data was attained regarding number of male patients, further analysis of the patients' presentation may supplement our current results.

This study did not analyse the patients (particularly their presenting conditions) at each individual first aid site. This is potentially possible (reference to Appendix 1 which proves the PRFs indicate the site of consultation) and would provide even greater details for understanding the medical demands at different out postings.

Conclusions

The results from our retrospective observational analysis of the Ahmadiyya Association annual gathering shows that there was a yearly increase in patients attended to with chronic conditions, posing a significant burden on medical care. The most common presenting conditions are similar over the years. Significant planning and organisation is necessary to ensure the appropriate care is given.

This data set may be useful in planning for mass-gathering medical care in the future. The variety of attendees in our data makes its findings appropriate for the planning of many events. Indeed, this data validates the need to determine the requirements for events in advance (Leonard et al, 1990). It can be used to formulate risk management plans and as the basis for framework and guidance for future teams and events.