Acute stroke is defined as a neurological disorder categorised by the sudden loss of blood flow to an area of the brain, resulting in the loss of neurological function. The three main classifications of acute stroke are ischaemic, haemorrhagic and transient ischaemic (Kuriakose et al, 2020). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2023) clinical guidelines state that acute stroke is the leading cause of death and disability, affecting more than 100 000 people and the cause of 38 000 deaths within the UK each year. The aetiology of stroke is influenced by detrimental lifestyle factors resulting in hypercholesterolaemia, leading to atherosclerosis and hypertension; patients diagnosed with cardiac arrhythmias have an increased risk of embolisms leading to acute stroke (NICE, 2022).

Posterior circulation stroke (PCS) accounts for up to 25% of ischaemic strokes and affects more than 20 000 people annually in the UK (Banerjee et al, 2018). Affecting the brain stem structures supplied by the vertebrobasilar arterial system, PCS is caused by a narrowing or blockage of one or more of the arteries that supply the brainstem, which can result in vestibular symptoms (Gulli et al, 2009). Patients presenting with PCS symptoms in the prehospital setting require the same emergency admission to hospital as those with other classifications of acute stroke (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2023).

Clinical practice guidelines (NICE, 2022; AACE, 2023) recommend the use of a validated stroke screening tool for the assessment of all patients presenting with stroke symptoms, such as the face, arms, speech, time (FAST) tool. Public health campaigns have recently been reissued to increase public awareness of this tool (Public Health England (PHE), 2021). A period of <6 hours between time of symptoms onset to hospital admission is associated with favourable outcomes for patients presenting with acute stroke (Matsuo et al, 2017; Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party (ISWP), 2023). Paramedics must make every effort to minimise time on scene and ensure that no unnecessary procedures that do not add value to patient assessment are performed (Matsuo et al, 2017; ISWP, 2023).

The FAST tool is used by all UK ambulance services for the assessment of acute stroke symptoms (McClelland et al, 2018). This practice is based upon recommendations in clinical guidelines (NICE, 2022) that prehospital assessment of acute stroke should be executed using a validated stroke screening tool, with FAST being specifically recommended. Relevant healthcare professional clinical guidelines (AACE, 2023) agree with this.

The FAST tool is deemed to have high sensitivity (Chen et al, 2022) and moderate specificity (Purrucker et al, 2015) in the recognition of ischaemic stroke. However, there is evidence in the literature demonstrating that the FAST tool is not adequate for prehospital screening of PCS, leading to misdiagnosis, treatment delay and severe life-limiting deficits or death (Sommer et al, 2017; Krishnan et al, 2019).

Typical stroke symptoms, such as face and limb weakness, are rapidly assessed using the FAST tool (PHE, 2021). However, patients with PCS may present with vestibular symptoms, which cannot be detected with FAST (Rowe et al, 2020). Furthermore, more than one-third of patients with PCS have a delayed diagnosis or are misdiagnosed because they do not display ‘typical’ acute stroke symptoms (Merwick and Werring, 2014).

High mortality from PCS has been linked to an inappropriate assessment tool being applied by clinicians, leading to incorrect triage, treatment and management (Rowe et al, 2020). Prehospital clinical guidelines recommend that paramedics have a high suspicion when patients present with vestibular symptoms, warning that not all stroke symptoms can be identified using the FAST tool (AACE, 2023). Furthermore, Rowe et al (2020) reported that pre-alerting a receiving hospital was the most influential factor for timely assessment of patients presenting with acute stroke. However, this study identified that hospitals were pre-alerted by paramedics only when stroke symptoms were detected using FAST. A more appropriate stroke screening tool used for stroke assessment, such as BEFAST (balance, eyes, face, arm, speech, time) (Aroor et al, 2017), coupled with improved paramedic awareness of PCS symptoms and stroke mimics, will directly improve PCS management (Oostema et al, 2019).

Recent changes to practice have occurred within American clinical guidelines, based upon the recommendation of the American Heart Association, following research conducted surrounding the BEFAST stroke screening tool. Aroor et al's (2017) study identifies that the addition of balance and eye assessments to FAST improves the detection of PCS symptoms. Furthermore, although BEFAST is not fully validated, it has pointed out that, if additions are needed to an already-validated stroke screening tool, this indicates a requirement in clinical practice that has not been addressed (Aroor et al, 2017). BEFAST is now commonly used within prehospital and in-hospital centres throughout the United States because of its efficiency in identifying PCS symptoms (Gulli and Markus, 2012; El Ammar et al, 2020; Meyran et al, 2020).

Several other research studies have found that vision and balance assessments can be valuable for improving prehospital detection of PCS and have produced positive results (El Ammar et al, 2020; Jones et al, 2021). Additionally, a recent study (McClelland et al, 2018) has suggested three UK ambulance services are using additional physical assessments alongside the FAST tool.

Aim

The aim of this literature search is to evaluate how the additional neurological assessment could be used alongside the validated FAST tool within the prehospital setting for better paramedic detection of PCS.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

An extensive review of the literature was undertaken using a variety of keywords: BEFAST, ‘stroke screening tools’, paramedic*, prehospital* and ‘posterior stroke’. Initially, the search was conducted using Academic Search Complete, MEDLINE and CINAHL databases from 2012 to 2022 to ensure contemporary evidence was sourced, followed by further analysis of other secondary searches, such as Google Scholar and the Trip database, plus scrutiny of reference lists. Boolean operators AND and OR were used within the search strategy to improve sensitivity and specificity of the results and to retrieve focused evidence.

A total of 46 articles were selected for review. The inclusion criteria were: assessment of stroke patients by any health professional including in-hospital and paramedics or technicians within the prehospital setting; and data sets reporting on accuracy of detection of stroke screening tools and/or signs and symptoms.

Studies were included if published in English, peer reviewed and available as full text. Exclusion criteria included duplication, non-English translated, no full text available, no direct link to PCS and non-stroke assessment.

Review method

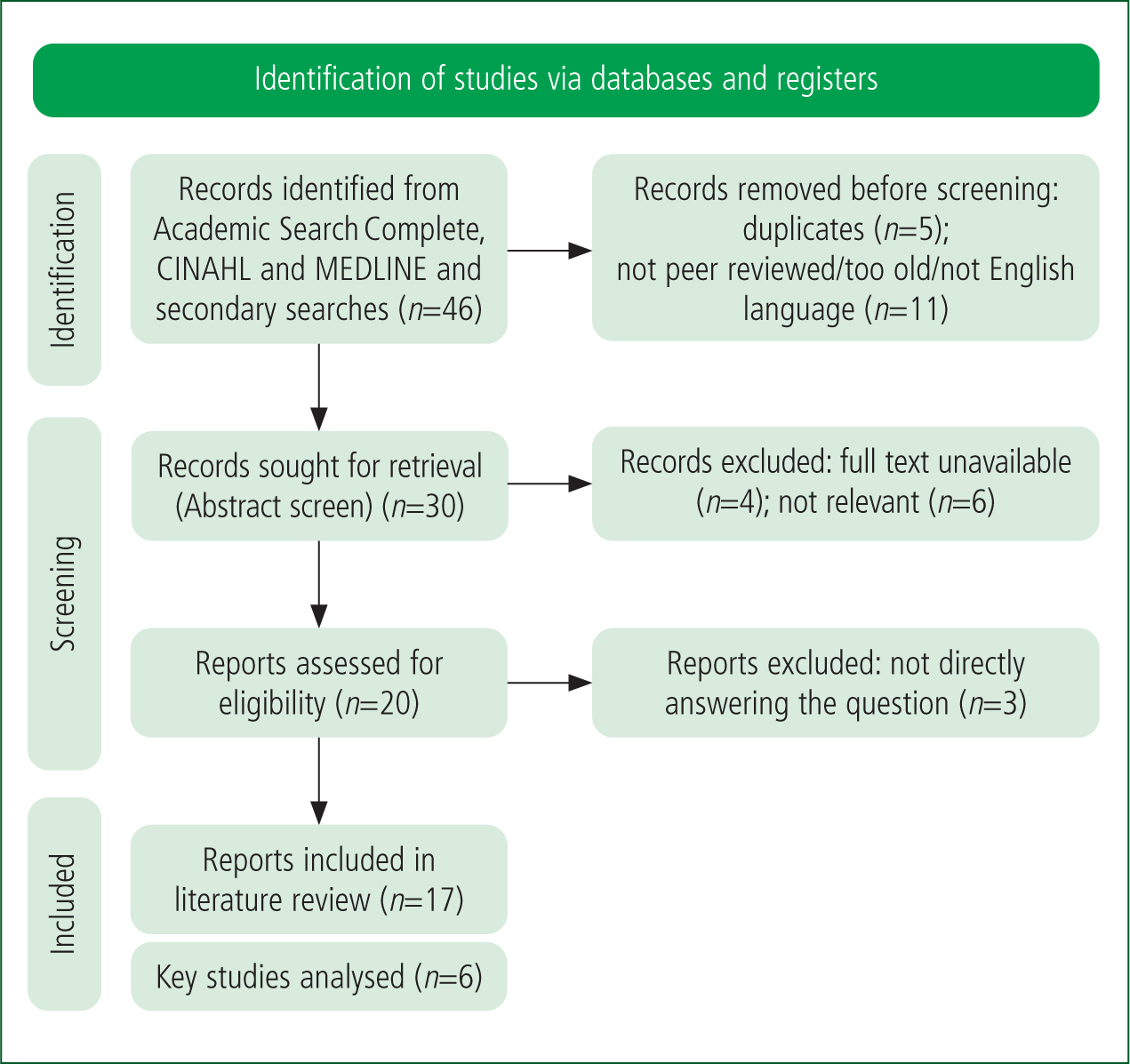

Results were analysed and combined within a PRISMA analysis (Figure 1) (Page et al, 2020) to locate the most appropriate evidence to answer the researchable question.

Seventeen articles were found to be of use to this literature review, and six chosen for comprehensive evaluation. The primary six pieces of evidence were appraised and placed into a literature matrix to analyse the evidence for inclusion within the review (Table 1). The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) systematic literature review checklist and cohort study checklist were used to validate evidence quality (CASP, 2023).

| Citation | Research methodology | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Aroor S, Singh R, Goldstein LB. BE-FAST (balance, eyes, face, arm, speech, time): reducing the proportion of strokes missed using the FAST mnemonic. Stroke. 2017;48(2):479–481. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015169 | Retrospective | The study was conducted to assess the prevalence of acute ischaemic stroke patients exhibiting symptoms not detected by the FAST tool. Additionally, the study evaluated whether incorporating assessments of balance and visual symptoms improved detection rates. The focus of the research was on sensitivity rather than specificity. A review was carried out of 858 records of patients admitted to University of Kentucky stroke centre with a final discharge notice of acute ischaemic stroke. The findings indicate that including balance and vision assessments resulted in fewer cases of stroke being missed. Missed diagnoses fell from 14% to 4.4% with BEFAST. The 95% confidence interval demonstrates improved detection of posterior circulation stroke (PCS), and the study has statistically significant findings (P<0.05). No increase in on-scene time was identified and no harm to patients was observed. However, the study was conducted at a single centre and within a hospital, which limits generalisability to paramedic practice. |

| Rowe FJ, Hepworth LR, Dent J. Pre-hospital detection of post-stroke visual impairment. International Journal of Stroke. 2017;12(5):51–52. 10.1177/1747493017732216 | Retrospective cross-sectional comparative | Hospital discharge notes for 84 patients with a formal diagnosis of PCS were reviewed to identify the types of visual impairment missed during assessment by paramedics and emergency department staff. This study found improvements were required to prehospital assessment methods for detecting posterior stroke. Furthermore, improved paramedic education was needed on the symptoms and differing presentations of PCS. The limitations identified in this study concern its retrospective methodology, possible inaccurate documentation within the reports and an inability to retrieve some patients' records, resulting in a small sample size. The study was conducted within a limited geographical region which will affect the generalisability of the results. |

| McClelland G, Rogers H, Price CI. A survey of pre-hospital stroke pathways used by UK ambulance services. Int J Stroke. 2018;13(3 suppl):35. 10.1177/1747493018801108 | Retrospective cohort | Ten UK ambulance services' data on stroke incidents were collected in May 2018 to identify if there was a regional difference in the stroke pathways. The study reported that UK ambulance services stroke pathways follow national clinical guidelines, and that cross-service standardisation could minimise variations in care and access to specialist services. The FAST test was used within each service in line with clinical guidelines requiring a validated screening test. However, one service included an additional assessment of balance and visual problems, alongside questioning on nausea and vomiting symptoms. The regional differences included variations in maximum time since symptoms onset to hospital admission, and differences regarding whether patients were treated in specialist centres rather than in emergency departments. Limitations were that compliance data within the services' dedicated pathways were not included, so the corresponding data could be skewed. Also, what was included in the data captured across services varied. |

| Oostema JA, Chassee T, Baer W, Edberg A, Reeves MJ. Educating paramedics on the finger-to-nose test improves recognition of posterior stroke. Stroke. 2019;50(10):2941–2943. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.026221 | Prospective | A finger-to-nose test was taught to 146 paramedics participating in a single county, with the aim of identifying whether the inclusion of a coordination/balance test alongside current assessment methods would improve identification of patients presenting with PCS. The authors reviewed pre- and post training records of patients diagnosed with PCS who were transported to specified stroke centres in the county to evaluate the inclusion of this test. There was a 28% increase in PCS recognition using the finger-to-nose test; adding this test to current stroke assessments improved detection of posterior stroke. The training and education provided around this test was also found to improve paramedic awareness of PCS symptoms. The techniques for this test were simple to teach, and no increase in on-scene time or harm to patients was observed. However, this study had a small sample size and was in one geographical location, which affects generalisability. There was also a limitation surrounding reporting bias as not all participants may have documented their findings in the patient report form. |

| Rowe FJ, Dent J, Allen F, Hepworth LR, Bates R. Development of V-FAST: a vision screening tool for ambulance staff. J Paramed Pract. 2020;12(8):324–331. 10.12968/jpar.2020.12.8.324 | Prospective cross-sectional comparative | The study was conducted to assess whether adding a visual test to the FAST stroke screening tool would improve diagnostic accuracy of identifying visual field defects in patients displaying stroke symptoms. Paramedics assessed patients with suspected stroke in the hyperacute phase of admission to hospital, using a 2-minute screening tool added to the FAST test. The test had a limited effect on time on scene and no patient harm was observed. It was found to have good sensitivity when screening for acute stroke, and improved detection of acute stroke in 75.9% of FAST-positive and 80% of FAST-negative patients with PCS. Paramedic awareness of visual problems within stroke presentations also improved. |

| Jones SP, Bray JE, Gibson JM et al. Characteristics of patients who had a stroke not initially identified during emergency prehospital assessment: a systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2021;38(5):387–393. 10.1136/emermed-2020-209607 | Systematic literature review | The literature review was conducted to identify the characteristics of acute stroke presentations with false negatives recorded by emergency medical services (EMS) and included 21 observational studies over 1995–2020. The review included studies on patients who had a stroke and were aged >18 years, where prehospital assessment was conducted by paramedics or technicians and data reported on prehospital diagnostic accuracy and/or presenting symptoms. The aims of the review were to evaluate additional neurological assessments in relation to the specificity and sensitivity of the tests included, to consider education and training paramedics needed to apply these additional assessments and evaluate the impact on current EMS resources. The review concluded that stroke symptoms specifically relating to PCS were often missed by current prehospital assessment methods, with 26% of patients with acute stroke not recognised by EMS. The most common false-negative symptoms documented were those for PCS. The findings suggest that the inclusion of additional assessments of vision and balance (including symptoms of vertigo, nausea and vomiting, and ataxia) improved sensitivity to PCS symptoms, but specificity was not determined. One study found no difference in identification compared to FAST. Limitations included that all studies were retrospective with small sample sizes. The authors were unable to ascertain the specificity of the additional balance and vision assessments as the patients in the studies already had a confirmed diagnosis of stroke. There is also a high risk of selection bias involved within the review, alongside the inclusion of only English language studies, so the full extent of analysable studies is undetermined. |

Results

A total of 46 studies were identified within the search strategy. Following the removal of duplicates and outdated/non-English translation, 30 studies were screened. After abstract screening, 20 studies were eligible for complete article analysis. Seventeen studies met the inclusion criteria, with six identified as being directly linked to the research question.

Of the six studies chosen to create the main themes for discussion, five were based in the UK and one in the United States. The methodology of each article was as follows: retrospective study (n=3); prospective study (n=2); and systematic literature review (n=1). Although not a primary study, the systematic literature review included significant underpinning themes and evidence for inclusion, and was directly linked to the research question and topics being analysed. Four studies were prehospital based and two studies took place in hospital. Thematic analysis identified studies focusing on comparison and evaluation of FAST versus other stroke screening tools (n=4) and consideration of additional assessments of stroke patients within stroke screening tools (n=5).

Discussion

Revised prehospital screening tool for improved posterior circulation stroke detection

A positive outcome for PCS relies heavily on early activation of the stroke ‘chain of survival’ by both prehospital and in-hospital staff (Herpich and Rincon, 2020). Atypical stroke presentation may lead to misidentification by paramedics so treatment and transport to a hyperacute stroke unit may be delayed, which exacerbates the potential for life-altering and life-threatening consequences of PCS (Hoyer and Szabo, 2021). The key to rapid recognition in the prehospital setting is efficient patient history taking, symptom analysis and the use of an adequate stroke screening tool, while maintaining a high index of suspicion for PCS when a patient presents with vestibular symptoms (Merwick and Werring, 2014).

The FAST tool has been included in all UK prehospital clinical guidelines since its introduction in 2009 because of its high sensitivity and moderate specificity in the recognition of ischaemic stroke (Purrucker et al, 2015).

There are several other stroke screening tools commonly used to assess and identify acute stroke, such as the Recognition of Stroke in the Emergency Room (ROSIER) scale (Nor et al, 2005) and the American National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) (Brott et al, 1989). Evidence suggests these are stepwise, easy to use and have high sensitivity for ischaemic stroke (Fothergill et al, 2013). However, they were designed for in-hospital use and research has found that both tools underestimate and give false negative results for patients with PCS (Alemseged et al, 2022).

The lack of an appropriate stroke screening tool for the detection of PCS has led to several primary studies being conducted to develop such a tool with an increased sensitivity to PCS symptoms.

Aroor et al (2017) aimed to determine whether the BEFAST tool would be more appropriate for the detection of all patients presenting with stroke symptoms, with the focus on improved PCS detection. It was determined that fewer ischaemic strokes, including PCS, were missed when balance and vision assessments were added to FAST. Similarly, Alemseged et al (2022) developed a modified NIHSS scale to include balance, vision and swallowing assessments for hospital inpatients. The results of this study had a higher prognostic accuracy than NIHSS alone. This evidence bolsters the rationale for change to a revised stroke screening tool for use in the prehospital setting.

The most valuable piece of evidence found is Jones et al's (2021) systematic literature review. The review's aim was to identify the characteristics of acute stroke presentations that were incorrectly documented by paramedics. Findings suggest that there has been no overview describing the non-classical symptoms of stroke inaccurately detected by paramedics, and no consensus on a prehospital stroke assessment tool to determine these symptoms. This review highlights several themes for discussion of value to this review, including the different stroke symptoms reported with PCS and the importance of rapidly identifying these symptoms.

Furthermore, this review located several studies that agreed that there is limited detection of PCS within the prehospital setting using the currently advocated FAST tool, with the recommendation that additional assessments to FAST are required (Jones et al, 2021). This article provides evidence that existing stroke assessment tools are unreliable in identifying common PCS symptoms, which supports a movement to including additional assessments for the improved detection of PCS.

Additional assessments of balance and eyes alongside FAST

Aroor et al (2017), Rowe et al (2020) and Oostema et al (2019) concluded that adding assessments of balance and vision to the validated FAST tool improved sensitivity for PCS symptoms. However, it was acknowledged within the studies that they could not determine the specificity of these additions regarding PCS symptoms and the exclusion of stroke mimics.

In contrast, Pickham et al (2019) reported no benefit in the additional assessment elements of’ BEFAST. Findings of their study suggested that stroke detection accuracy was comparable, with facial droop and arm weakness named as independent predictors of acute ischaemic stroke.

However, closer analysis reveals several limitations. The study was conducted within a single centre and had a small sample size, and it is clear within the methodology that the BEFAST tool was applied only to patients presenting with presumed stroke symptoms within 6 hours of neurological deficits. Evidence suggests that outcome reporting bias, where there is selective non-reporting of data or only a subset of evidence is reported, is a critical issue within the assessment of health-related interventions and can affect the overall outcome of a study (McGauran et al, 2010). This begs the question of whether there was outcome reporting bias present in this study, as there may have been patients who had neurological deficits outside this time criteria, the initial emergency call-taker may not have coded the incident as query stroke and the paramedics may have inadvertently missed PCS symptoms. Furthermore, this study aimed to detect the prognostic accuracy of acute stroke using the BEFAST tool, not specifically around PCS detection.

The consensus on stroke assessment within United States ambulance services has made a distinct change by using the BEFAST tool based upon the recommendations of the American Heart Association. Aroor et al's (2017) study was the catalyst for change within the American stroke guidelines. The results of this study are statistically important (95% confidence interval and P<0.05), with 14% of stroke diagnoses missed with FAST alone, falling to 4% with BEFAST applied. It concluded that the addition of balance and vision assessments leads to a reduction in missed acute stroke, with no risk to patient safety and no increase in ambulance on-scene time. However, American ambulance services are configured differently from those in the UK so the generalisability of results needs to be considered before a step change can be made based upon this evidence.

Identifying additional assessment inclusion

An essential aspect of this literature review is to identify which physical assessments should be included within the additional neurological assessments, and the extra skills that paramedics will need.

Within current practice, neurological assessment of patients includes assessing limb weakness, strength and grip, level of consciousness, facial symmetry, pupillary response, blood glucose and mobility (Blaber, 2021; AACE, 2023). Extended clinical assessments require consideration of the paramedic scope of practice, with Jarva et al (2021) identifying that some additional stroke assessments require strong clinical competency. Any assessments included for improved PCS detection must align with paramedic skills or be deemed appropriate for the paramedic scope of practice and would require increased education for paramedics to improve understanding of the altered neurological anatomy and physiology of patients with PCS.

Krishnan et al (2019) examined the accuracy of the HINTS (head, impulse-nystagmus-test of skew) examination for the assessment of patients presenting with vestibular symptoms associated with PCS. Dizziness, vertigo symptoms and ataxia are commonly found with PCS, and the HINTS examination assesses nystagmus, head impulse and skew deviation of the eyes. This assessment was deemed to improve the accuracy of PCS detection; however, in seriously ill, highly nauseated patients, or those with severe neurological deficits, the HINTS examination would be difficult to perform. Furthermore, this tool is primarily performed in hospitals by senior specialist physicians with neuro-ophthalmology training as specialist techniques are required. It is therefore not appropriate for the prehospital setting.

Similarly, Alemseged at al (2022) included the assessment of ataxia, visual acuity, nystagmus, dysphagia and tongue deviation. The additional assessments to the NIHSS stroke scale demonstrated improved prognostic accuracy of PCS. However, this tool was produced for in-hospital assessment, where specialist training in dysphagia and oral examination is standard, alongside radiological imaging. Upon reflection, several of the assessments included in HINTS and NIHSS would require in-depth specialist training and expertise that is beyond the scope of practice for paramedics and, if implemented, would greatly increase on-scene assessment time. Furthermore, these tools would require extensive staff education and training to be used correctly. However, pupillary constriction and visual acuity assessment could be readily conducted by paramedics with limited additional training required.

Rowe et al (2020) included an additional 2-minute vision test to FAST noting reading ability, eye position and movement, visual field assessment and visual extinction assessment. Similarly, Huwez and Casswell (2013) assessed blindness, diplopia and pupillary abnormalities, as well as ataxia. According to the study, 83% of the patients who had the additional examinations were diagnosed with stroke, compared to 66% with FAST alone. Aroor et al's (2017) study included assessments of gait imbalance, visual acuity and pupillary abnormalities, noting an improved recognition of acute stroke, because vestibular symptoms associated with PCS were identified.

However, limitations were noted with each of these studies. It was concluded that the vision test had limited specificity because of false positives and the practitioners were unable to determine whether the visual deficits were new visual presentations (Huwez and Casswell, 2013; Aroor et al, 2017). The overarching conclusion from the evidence is that visual and ataxia assessments could be added to FAST and readily applied to patients in the prehospital setting, with reading ability, eye movement, and visual field assessment included for improved PCS detection.

The studies discussed above provide confidence in applying additional assessments within the prehospital field, concluding that the assessment of gait, visual acuity and pupillary constriction could be incorporated into the existing FAST screening tool to improve detection of PCS. There may be a small extension to on-scene time, yet this needs to be balanced with the benefits of improved PCS detection. It is anticipated that these physical assessments will not require any major deviation from current paramedic skills and be within the paramedic scope of practice.

Review limitations

This review's limitations include the author's interpretation and decision-making regarding the included material, data abstraction, critical analysis and synthesis for evaluation. Additionally, since this is not a systematic literature review, there may be other primary evidence not sourced within the searching process.

Conclusion

The evidence examined demonstrates a gap in practice, whereby a combination of a lack of education coupled with poor understanding of PCS is affecting prehospital PCS detection.

Additional neurological assessments, carried out alongside validated FAST stroke screening, could improve paramedic detection of PCS; the inclusion of gait assessment, visual acuity and pupillary constriction would sit within the current paramedic scope of practice.

Further research is needed into this topic regarding the education paramedics would need, and the formulation and implementation of a new prehospital stroke screening tool for improved PCS detection.