With the university route being used to educate our future paramedic workforce before entry onto the professional register, this article explores the ways that experienced paramedics and technicians make clinical decisions and undertake patient assessment; comparing these with the methods used in this area by student paramedics.

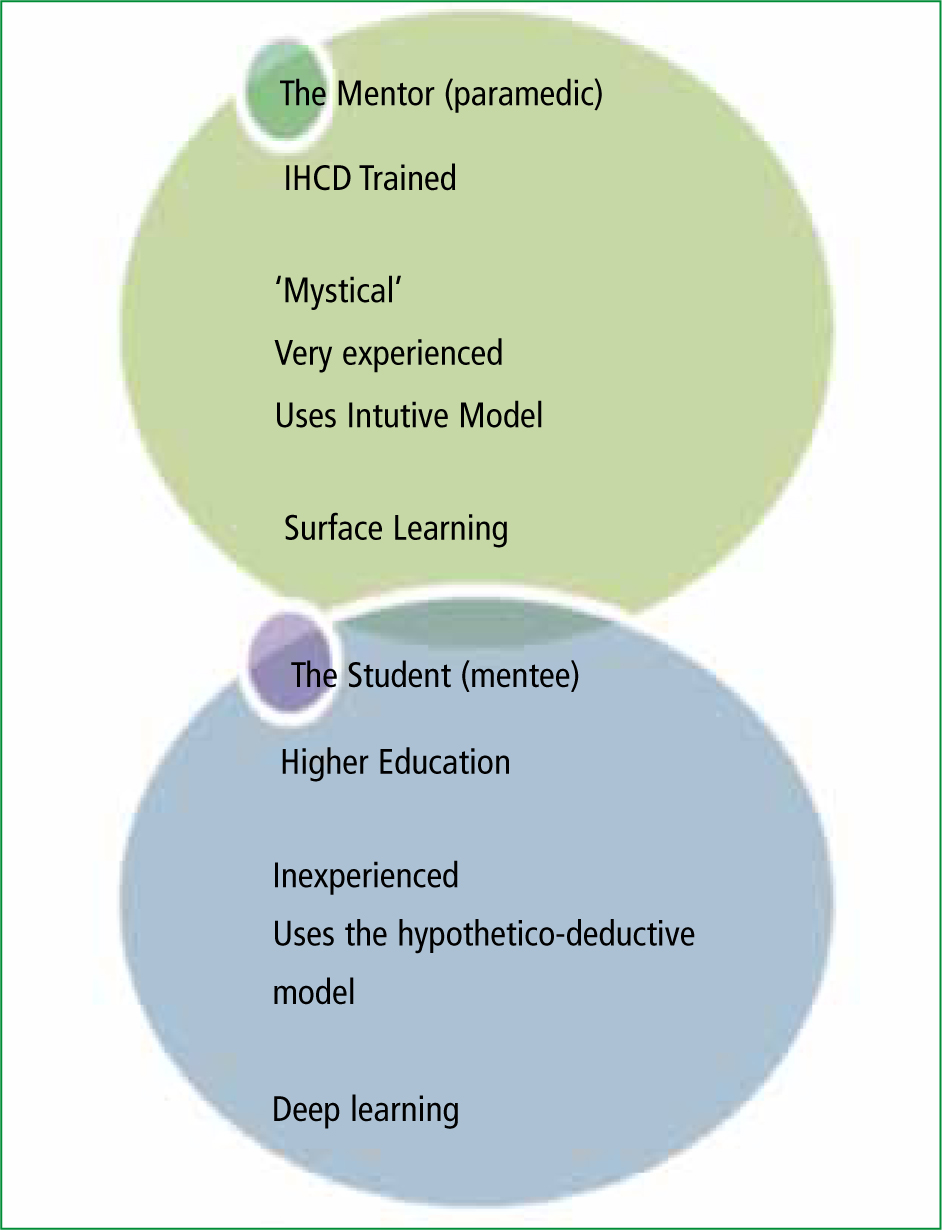

In addition, this paper will explore the possible causes of friction between mentor and student, and will link this to the methods of education used for ambulance clinicians. The authors feel that an understanding of the potential frictions between paramedics who have been educated using higher education, and mentors who have experienced previous Institute of Health Care Development (IHCD) based vocational education, will assist both parties when reviewing the student paramedic/ mentor relationship.

The authors are both studying for doctorates and as part of two independent empirical studies that have both received research ethics approval. Study One uses a mixed methodology to research the learning approaches of paramedic students, specifcally looking at surface and deep learning in two sample groups of students, 30 from a local university and 30 students who have graduated as paramedics from an IHCD Programme (Halliwell, 2011)

Study Two uses a case study approach with phenomenology and hermeneutics, and involves the comparison of two sample groups of students from a foundation degree and a BSc (Honours) degree at two local universities using interviews, focus groups and questionnaire surveys. Study Two considers whether the students are road or practice ready on graduation (Ryan, 2011). The sample groups in this study involve 30 students on a foundation degree, 50 on a BSc honours degree, 30 employing managers, all of whom were IHCD trained, and eight tutors (four from each university) all of whom were IHCD trained. This article will use some statements made by participants in these two studies to support the arguments made; but cannot provide statistical evidence at this time as the doctorates are still in progress.

When examining the decision-making of paramedics and technicians, it was important for the authors to consider the lessons that could be learnt from other professions, particularly nursing, that have had similar models of mentorship; and who have been through similar changes in education strategies to those currently being experienced by paramedicine in the United Kingdom (UK). In the last 10 years we have seen changes to the way that nurses are educated, and nursing education has movedfrom a nursing school education with a national examination process leading to state registration, to a graduate profession. This change was due to the demands on the profession (Bernhauser, 2010) requiring more complex education and development as the profession moves towards the delivery of 21st century healthcare. Now there is a need for healthcare professional with advanced practice skills and a wider knowledge base. In comparison, paramedic education is moving towards the graduate profession following the recommendations of the Bradley report (2005), which endorsed a move towards a graduate profession with the development of practical skills in a variety of clinical settings to expand and enhance the skills attained. The report recommended multiple entry points supporting certifcate, diploma and degree level study, with two routes, a vocational and a more academic route.

The development of paramedic education

In 1966, the Millar Report (Ministry of Health) recommended intensive training for ambulance personnel that included frst aid, care of the seriously ill and the required skills following accidents and sudden illness. In 1973, the NHS Reorganisation Act (Great Britain, 1973) transferred control of the ambulance services to the NHS, who realised that ambulance services could also provide emergency care (Howson, 2011). In 1988, following their establishment in 1984, the NHS Training Authority (NHSTA) were given responsibility for the management of all National Staff Committees (BMJ, 1981) and assumed accountability for ambulance training policies and award systems (Howson, 2011). This formalised the internally run ambulance service educational development (Caple, 2001). In 1991, the NHSTA became the NHS Training Directorate and part of the NHS Executive; in 1993, it became the NHS Training Division (NHSTD), splitting in 1995 into the NHSTD (Core) and the NHSTD (non-core), dividing the responsibility for policy and award delivery. In 1996, the NHSTD (Core) became the Institute of Health and Care Development (IHCD), taking responsibility for operational activities, and the Ambulance Awards and NVQs were developed in partnership with the Open University. In 1997, the Privy Council recognised the paramedic profession, and the Ambulance Services Association (ASA) took responsibility for ambulance training with the IHCD continuing to deliver Ambulance Awards. Registrants were required to hold the NHSTA/ IHCD Paramedic Award. In 1998, Edexcel acquired the IHCD, and the institute became the IHCD Healthcare Limited (Howson, 2011).

Bradley (Department of Health, 2005d) called for the creation of ‘a workforce that can provide a greater range of mobile urgent care’, and a multi-disciplinary approach to education, recommending a move from the vocationally based courses provided by the IHCD and run by tutors trained and developed using their instructional methods and qualifcation courses.

These courses included the ambulance care assistant course, developing the support worker, a fve-week competency-based skills training and a driving course; the technician course, developing the assistant practitioner, a seven-week competency-based skills training and highspeed driving course and the paramedic course, developing the practitioner, a nine-week theoretical programme with a period of consolidation in the practice setting. These courses provided clinical skills sets but not the holistic approach to professional education required by the QAA (2004) and Bradley (Department of Health, 2005).

The IHCD curriculum and design involved learning clinical skills (Kilner, 2004) underpinned by knowledge of signs and symptoms, with the use of protocol driven practice. This system was criticised by a number of authors as it was based on the provision of a limited under-pinning knowledge (Williams and Woollard, 2002), rather than more complex levels of cognition. Kilner (2004) in particular, in his study on the desirableattributes of ambulance staff, concluded that theeducational curricula did not seem to provide theambulance services with the necessary attributesrequired to meet the demands of their workloads;suggesting that students required a greaterknowledge of minor injuries, and a focus on anunderstanding of the conditions that ambulancecrews most commonly see.

The IHCD route to education tends to foster surface rather than deeplearning (Cooper, 2005), and to support this mnemonics are often used to remember, for example, the order of the cranial nerves. Williams and Woollard (2002) stated that the IHCD route tended to concentrate on life saving conditions with protocol driven practice, based on a limited underpinning knowledge. Cooper (2005) recommended that the curriculums movedfrom surface learning towards an adoption of deepthinking strategies; suggesting that paramedicinewould beneft from the use of questioningevidence based practice. He implied that theIHCD system at that time focused on learningthrough memorisation, which encourages thesurface learning approach, rather than allowingstudents to really gain a thorough understandingof their subject matter, the deep learning approach(Ramsden, 1992). Surface learning does not alwaysfoster an understanding of our subject, and it can be relied upon to learn facts, or categorise them into an order, rather than encouraging us to make informed decisions; since to do so we would require a greater understanding of HOW, and WHY (Ausubel, 1968). Deep and surface are two approaches to studying, derived from original empirical research by Marton and Säljö (1976) and subsequently elaborated upon by Entwhistle (1981), Ramsden (1988; 1992) and Biggs (1987; 1993).

Table 1 contrasts some key attributes of deep and surface learners and explains some of the anxieties that exist about the use of vocational education. The IHCD system was historically a ‘short course’, typically 6–8 weeks in duration followed by 4 weeks of hospital placement. It comprised of modules, with regular examinations that were based upon a pass or fail examination system.

In Study One (Halliwell, 2011) it was found that that students on the IHCD programmes were often focused on ‘passing the next exam’, and they tended to ask the tutors question like ‘what areas most commonly come up in exams’. It should be noted that the IHCD system has produced 80 % of the author's trusts current paramedic workforce (South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust Workforce Plan 2011), many of whom have gone on to study at higher academic level and to study for post graduate awards.In addition, many of our practitioners and consultant grade staff started their careers within the IHCD education system.

Ball (2005) recommended a move away from a focus on learning via memorisation of facts and application of clinical skills, and proposed a move towards higher education, believing that this would create an environment for…'fostering the ability to think and practice autonomously' (Ball, 2005) providing university educated paramedics who could appropriately diagnose and manage a wider patient range.

This and other key government papers, such as the Bradley Report, Taking Healthcare to the Patient (2005), made education and career development a key area for NHS ambulance service development. The ambulance services, however, have only just begun the move to higher education, and this focus was repeated as recently as 2011 in the publication from the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (ACEG) Taking Healthcare to the Patient 2; a review of 6 years progress and recommendations for the future, that stated: ‘To aid integration, there should be a move to higher education delivered models’. The ACEG (2011) publication goes on to state that: ‘Higher education for paramedics is central to achieving a modernised ambulance workforce that is able to provide a greater range of mobile urgent care. Making the transition will equip ambulance clinicians with a greater range of competences and underpinning knowledge while maintaining the vocational nature of their training. It will also aid integration with the wider NHS, making it easier for staff to move to and from ambulance roles within their careers'.

This publication still refers to knowledge and skills rather than the application of that knowledge by the clinicians; but the authors of this article perceive that it is not so much the education method that is of value, but rather it is the teaching of how knowledge can be applied which is of the utmost importance.

Clinical decision-making

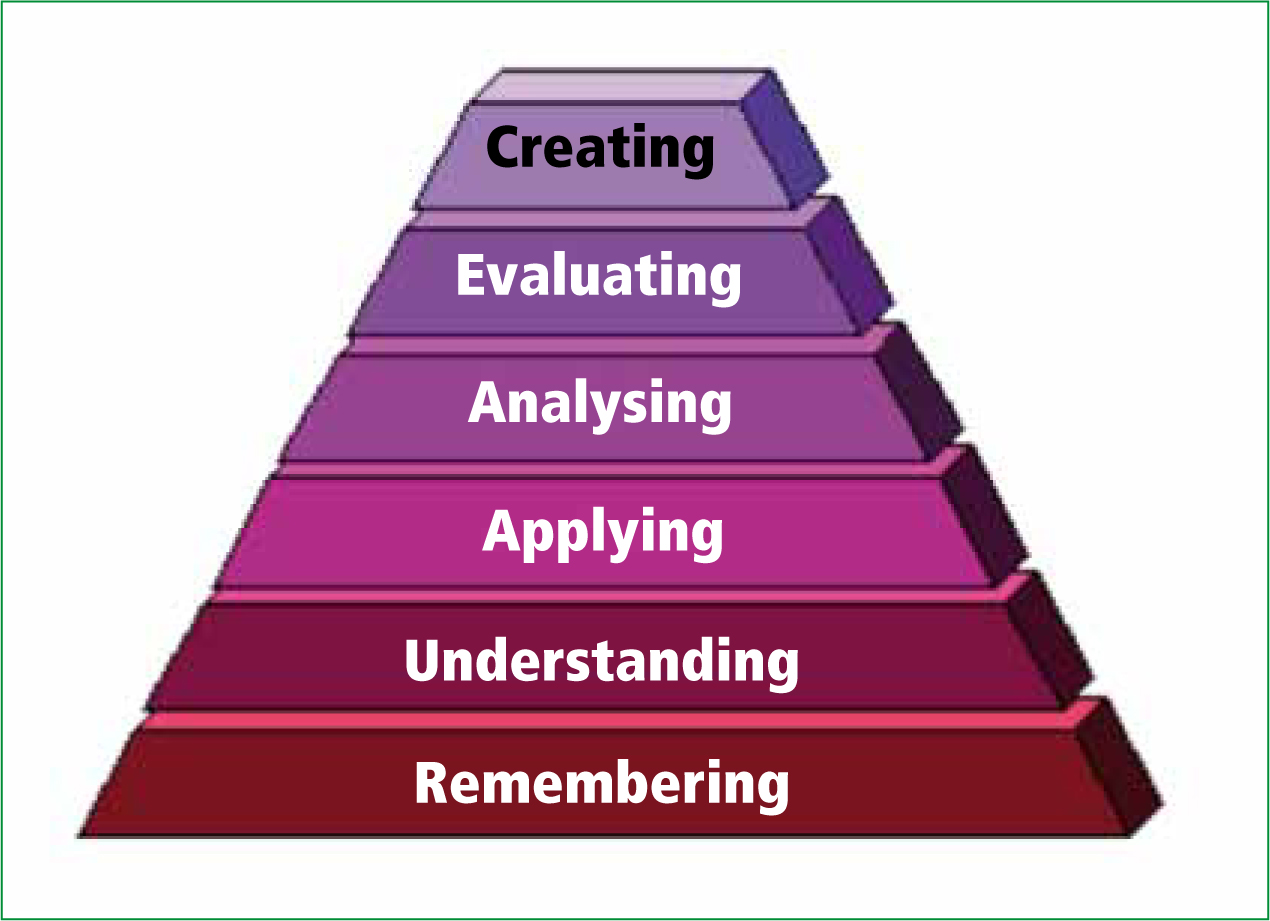

Clinical decision-making is a highly complex process encompassing cognitive, intuitive and experiential processes (Pugh, 2002). Cognition involves knowing the facts. Pohl (2002) described the cognitive domain originally describe by Bloom (1956) and updated by Anderson and Krathwohl (2000) (Figure 1), seeing the remembering as the bottom level; where the learners gain the knowledge and then goes through six stages including: remembering; understanding; applying; analysing; evaluating and creating to reach contextualisation (judgement) of the material in front of them.

Other experts suggest that most decisions are made either hypothetico-deductively or intuitively (Buckingham and Adams, 2000; Riley, 2003; Muir, 2004).

Hypothetico-deductive reasoning

Hypothetico-deductive reasoning in clinical decision-making involves making conscious clinical hypotheses that are scientifc and open to scrutiny (Riley, 2003). For Paramedics there are three important concepts:

Of the two universities studied in Study Two both appear to educate their students in the use of hypothetico-deductive reasoning. It is suggested that the student paramedics in universities are now being educated in the use of this method of enquiry, following a structured approach to gather information (Figure 1). An example of this is the reviewing of the signs and symptoms in a (C )ABCDE format (Halliwell et al, 2011) in order to rule in or rule out the presence of clinical fndings and observations. Users of this approach subsequently base their treatment actions upon their fndings. As an example, in the presence of a catastrophic haemorrhage there is a need to use an arterial tourniquet to control a catastrophic haemorrhage before attempting to secure an airway, ruling in. If no catastrophic haemorrhage is present then the clinician should move on to assessing the airway, ruling out. The IHCD programmes encouraged the use of the hypothetico-deductive reasoning; however of the 30 managers and 8 tutors studied in Study Two (Ryan, 2011) all stated that they moved into an intuitive approach after gaining experience, and rarely used the mnemonics taught.

The structured approach to pre-hospital care is now the basis for many of the formal courses taught in the UK, both civilian and military, adult and paediatrics; including Advanced Life Support Group Advanced Life Support (ALS) courses; Paediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) courses; the Royal College of Surgeons Pre Hospital Trauma Life Support courses and Anaesthetics Trauma and Critical Care courses (ATTAC). All of these courses focus heavily upon the structure and learning of a procedure as well as the acquisition of new clinical skills, rather than focusing on decision-making.

Reliable patient assessment

In a study carried out by Manias et al (2004) graduate nurses studied were found to be using hypothetic-deductive decision-making, which increased the reliability of the data gathering process. In this study they found that intuition, the other principle method used to make decisions, was only used slightly. One area that the newly qualifed graduate nurses in the study struggled with was having confdence in their decision-making and hypothesis; the research found that the addition of decision-making processes or templates helped them (Tanner, 2006).

The use of templates and evidence to gather clues or data from signs and symptoms of illness or injury or from patient histories all require the data to be gained in a structured way to ensure key areas are assessed by their priority. Data is collected to enable the pre-hospital clinician to make decisions and identify previously known patterns in the patient's presenting signs and symptoms. The authors have previously published an article on primary survey and the ways in which the practitioner can use a structured approach, as they make clinical decisions, the approach prioritises and orders the decision-making process (Halliwell et al, 2011). In addition, the structure provides a form of safety netting to ensure that all aspects of the decision-making process are ruled in or ruled out; so ensuring that no aspects of the patients condition is missed is missed (Riley, 2003). The drawbacks of using templates to assess patients are around the inaccuracies that the decision templates could have, or that a potential action that may be missing, and the practitioner is dependent on the accuracy of template design and their interpretation of the patient's presenting condition (Buckingham and Adams, 2000). The decision-making process needs to consider, in addition, that events can involve uncertainties (Orme and Maggs, 1993), and any reasoning process must allow for some intuition to come into play about the benefts and consequences of any decision made (Wooley, 1990).

Intuitive reasoning

Another model used in the paramedic decision-making is intuitive reasoning; this is used by many of the paramedics in the UK who may not have been formally educated to undertake skills using a structured approach (Figure 2). In Study Two, out of the 30 managers and 8 tutors interviewed, all of the managers and some of the tutors stated that their confdence in their ability to make decision and the recognition of recognisable patterns in patients made them use their gut and intuition to make a decision. In comparison the graduates from the universitiesfelt more confdent having a template to follow and depended on hypothetico-deductive reasoning because of their lack of experience and confdence in their ability. In comparison the graduates from the universities felt more confdent in having a template to follow and depended on hypothetico-deductive reasoning because of their lack of experience and confdence in their ability.

Benner (2001) found that student nurses that they could take from 18 months to three years to develop the confdence to act on their intuition. The experienced clinicians, like the managers and tutors in Study Two have been exposed to many thousands of patient contacts upon which to base their clinical decisions. Intuitive reasoning in clinical decision-making, involves the ‘immediate knowing’ of something without signifcant conscious thought (Thompson and Dowding, 2002) and involves decision-making that is based on past experience and so-called gut feeling); and the experienced clinician, like the managers and tutors in Study Two, has been exposed to many thousands of patient contacts upon which to base their clinical decisions. In addition, intuition can also involve decision-making based on the use of the intuitive part of the process to inform the assessment and the ruling in and ruling out process (Riley, 2003) can also involve decision-making based on the use of the intuitive part of the process to inform the assessment and the ruling in and ruling out process (Riley, 2003).

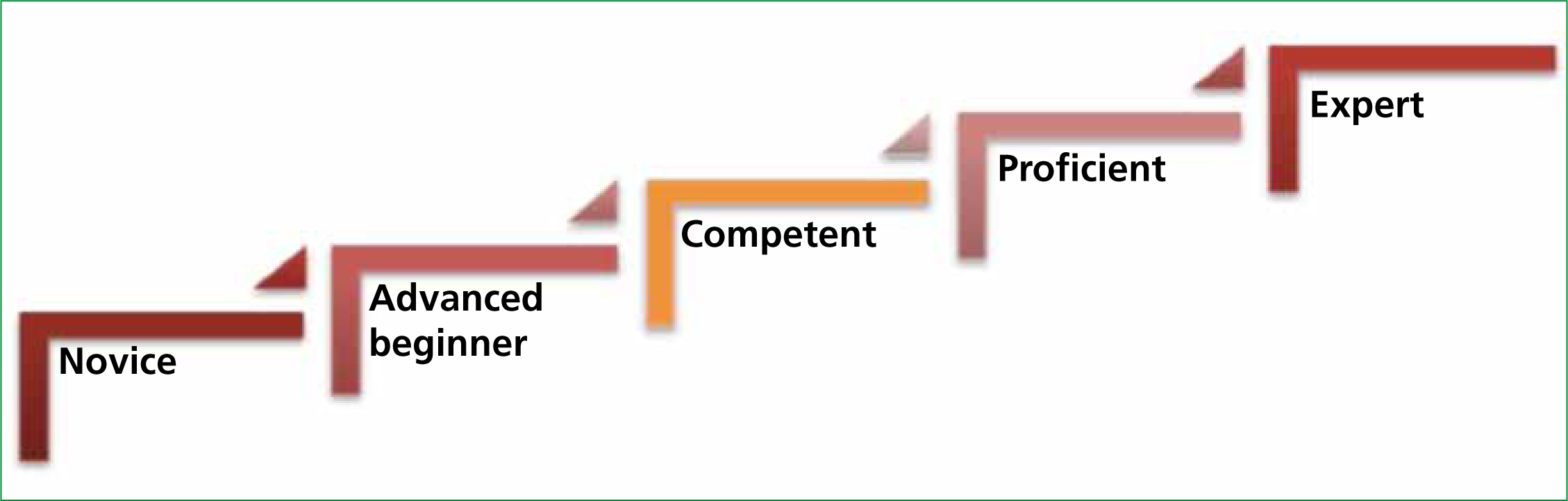

Buckingham and Adams (2000), in their study involving nurses, stated that there is a kind of mysticism in intuitive reasoning, suggesting that the use of intuition may detract from the professional status of those who use this method to base their decision-making on. Interestingly Benner (2001) had previously published an opposing view explaining that an intuitive approach distinguishes the expert from the novice, basing her studies on the Drefus (1980) model of skill acquisition (Figure 2). She looked at the role of intuition in nursing, suggesting that experts no longer rely upon structured principles to connect their understanding of clinical situations to the appropriate action, but do so automatically. This view could, however, be argued against on the grounds of patient safety, since by using a hypothetico-deductive method it is very unlikely that a clinician will be likely to make a mistake providing that they have the suffcient underpinning knowledge and experience, compared with those whose decisions are not really based on science, and are sometimes quite diffcult to justify. Sox et al (2007) suggest that most doctors also tend to use the hypothetico-deductive method and consider the use of differential diagnoses to consider the possible causes of a conditions before making a diagnosis.

During Study Two, 30 managers and 8 tutors, who were experienced paramedics, were asked if they use any form of template upon which they make their decision, not all could explain how they make their decisions, referring to experience, intuition, and gut feeling. Study Two could be related to the education provision in other universities providing a paramedic degree because the guidelines for programme design are the same wherever the programme is being run in the UK, and are governed by the same regulatory bodies. It could also be applied to ambulance services as they have the same job roles, and the role requirements are governed by the Knowledge and Skills Framework (Department of Health, 2004).

Experienced paramedics can use the semi-structured approach employing the mnemonic and rote memorisation, since some decisions can be predicted under a controlled circumstance. An example of this is the management of a cardiac arrest; however, we need to accept that the pre-hospital world is complex, with multiple competing factors that are specifc to the individual patient/s, and often with a unique set of issues dependent on the psychosocial and health condition of the patient.

In South Western Ambulance Services NHS Foundation Trust (SWAST), over 300 senior paramedics have enhanced their skills and abilities using university programmes, such as BSc(Hons) degrees; and coupled with their experience, have become extensively qualifed and capable practitioners. In advanced practitioner training days the training staff have found that they use both the hypothetico-deductive approach to reasoning and the intuitive and experienced based approach to support their decision-making. In addition in SWAST, as part of the continuing professional development (CPD) process senior paramedic practitioners are educated to use a hypothetico-deductive structured medical model of patient assessment, and follow such protocols as the Ottawa ankle rules.

The intuitive model has a relationship with experience (Banning, 2005), and this ‘experience bundle’ brings increasing value to the clinical decision-making process the more experienced we get. This model, however, lacks the conscious thought associated with hypothetico-reasoning; there is a lack of scientifc decision-making, a reason for the decision. We could also argue that if the decisions made are not easily described or communicated to another person they may struggle when subjected to peer review; hence the mysticism that surrounds the intuitive part of the decision-making process reported by Buckingham and Adams (2000).

Intuition requires previous knowledge related to previous experience (Schrader and Fischer, 1987). An example of this is when paramedics recognise patterns of clinical fndings or presentations they may compare them to similar patterns they have seen before. For example, pale, cold, clammy skin indicates clinical shock and absence of radial pulses idicates possible hypotension. This pattern recognition method of using intuition on which to base clinical decisions (Higgs and Jones, 1995) is described as a powerful component of clinical practice. It has its weaknesses, however, since it is dependent on the number of recall pattern sets the practitioner has, the variations that can occur from patient to patient and the conditions that could masquerade as a particular pattern (Murtagh, 1994). In addition, the cues may not be associated with the correct decision and could be inaccurate (Banning, 2005). The one way that students/ learners can learn intuition is by observing the experienced practitioner, but this could be affected by the individual's perception of what they see and may be inaccurate (Thompson, 1999).

The friction between mentor and mentee; the student comment

Often it is the simplest comments that create a new area of research or study, and in this case, this entire paper was born from a student comment that we are sure many readers of this article may recognise:

My mentor doesn't seem to use a structured approach.

This phenomenon is possibly true, the experienced clinician and mentor may never have been educated to use a structured approach within his initial IHCD training, and may be relying on intuition and experience upon which to base their decisions; but in doing so they defnitely create confusion in the university students, and potentially place themselves and their patients at harm.

The authors of this article believe that we need to educate our students so they understand that our mentors are often using their experience to base their decisions upon, and most of the time this is safe practice. We need to explain to our students why we do not want them to copy the mentor. In addition, we need to show our more experienced, IHCD educated, staff that there is beneft to them, and their patients, in learning how to use a structured approach, applying it as and when necessary.

The friction between mentor and mentee: the mentor comment

Another recent comment to one of the authors has created further concern:

My mentor says I don't need to bother with all this (C)ABCDE stuff, he says if I just treat the signs and symptoms—I can't go wrong.

This comment suggests that we need to educate our clinicians and mentors in the reasons why we need our students to follow a structured approach. University students often lack clinical experience; and may not have suffcient, upon which to base a gut feeling. Without having a structured template upon which to base their decisions, we would argue that the university student has no model with which to synthesise their fndings. Again, this comment suggests a need to educate our mentors, not only in the skills the student needs to practice, but how and why they are taught that way.

Maybe our experienced clinicians are able to treat what they see, and what the patient tells them, and rarely make mistakes; but the authors suggest that this approach is outdated and a treatment regime based on signs and symptoms alone is unlikely to support modern requirements of clinical practice.

The authors of this article would question is the whether the protocol driven, surface thinking approach described, and criticised by Kilner (2004), Ball (2005) and Cooper (2005) is still with us, or can we use both approaches to support clinical decision-making?

A combination of approaches

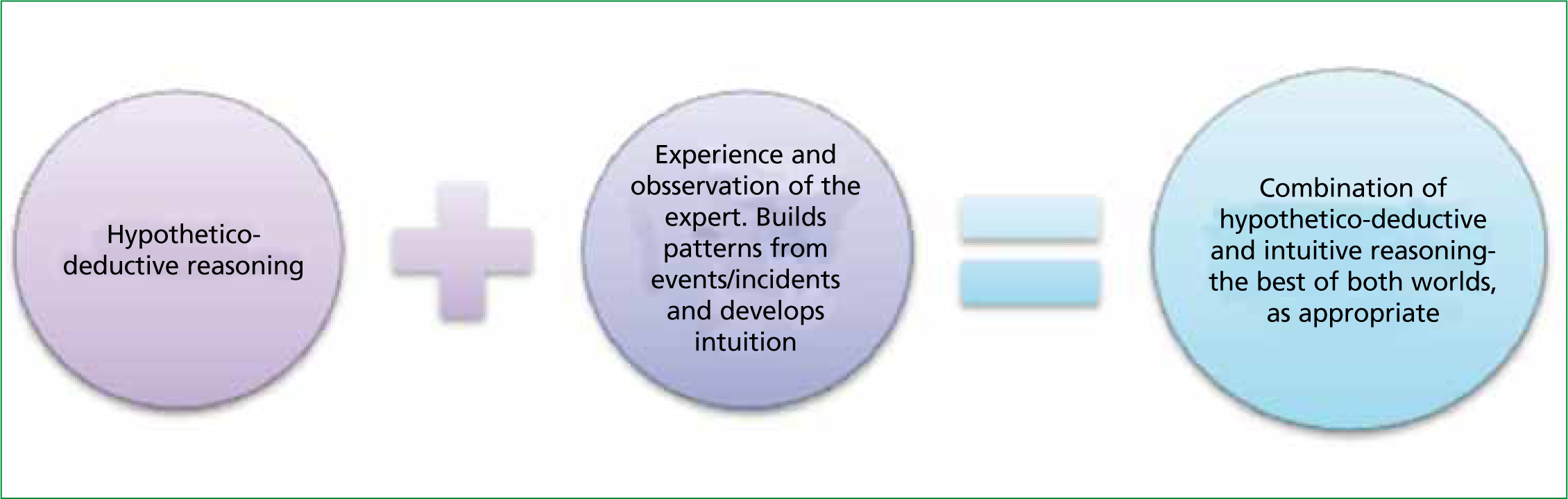

If we are to gain the ‘best of both worlds’ we should, as recommended by Thompson (1999), consider developing both elements of the decision-making process. Hamm (1988) considered this ‘cognitive continuum’ in medicine, and concluded that medical practitioner cognition is often neither intuitive nor analytical but lays somewhere between the two (Figure 3).

An example of this in paramedicine would be the use of the (C)ABCDE patient assessment process used by a paramedic, the hypothetico-deductive reasoning, versus a need to minimiseor rush some areas of patient assessment because of the need for more timely transportation. The decision may be based on a ‘gut feeling’ that something is happening to the patient, and that the best place for the patient is in theatre. The paramedic may chose to transport the patient rather than stay and play due to that intuition; but it is this type of decision that isoften one of the more diffcult to articulate.

Hamm (1988) stated that if the practitioner does not know that there is an acceptable and evidence based principle behind the reason for a specifc treatment or action then hypothetico-deductive reasoning is unlikely to be used; and intuition becomes the driver. This could be a concern to paramedics who may be performing tasks without really understanding why, who have been taught how to do something and have done it that way for many years. We suggest that teaching the evidence behind why, and not just how paramedicine should be performed, is essential, and that we must target our existing clinicians as well as our university students. Eccles and Grimshaw (2000) stated that ‘evidence is not self implementing’; in order to change practice we need to develop knowledge and skills through education and effective communication (NHSCRD, 1999).

Benner (2001) stated that good decisions are made intuitively by professionals with expertise, and suggests that the novice, beginner, student and newly-registered graduate, should be governed by rules, templates and guidelines, mnemonics until they have gained enough experience to recognise the patterns in the events/incidents that they perform in (Figure 4).

In summary, we suggest that there is a place for both approaches to reasoning and the choice is dependent on the situation that the practitioner fnds themselves in, and the level of expertise that they have in any given situation. Hypothetico-deductive and intuitive decisions should not be seen as opposite sides of the reasoning continuum but as poles along a continuum that can be used in any situation dependent on a number of factors. In the uncertain world that the paramedic works in no one solution will meet all requirements, but a mix of both reasoning approaches will help the practitioner to deliver the correct care in most environments.

We further suggest that the practitioner's professional registration would be better protected by the use of a structured, hypothetico-deductive approach, since this approach is evidence based and will withstand peer review. We need to explain to students that there is a place for intuition, but also that their system of patient assessment and decision-making is taught to them to ensure their practice, and therefore their patient, is safe.

We further recommend training all mentors to use a structured approach and teaching them to understand hypothetico-deductive reasoning; encouraging mentors to allow students to use the methods that they have been taught. We hope that this paper provides a template for peer discussion, and ask the reader to contemplate the following question:

The authors hope that the answers to both questions will lead the refective reader towards a greater understanding of the need to ask the questions ‘why?’, ‘how?’ and ‘who says?’