Confidentiality in healthcare has its origins in the Hippocratic Oath (Jackson, 2013) and appears in professional codes including the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) Code of Conduct, Performance and Ethics (2012a). Concepts of confidentiality and information sharing are well established in health and social care but there can be difficulties in practice (Health and Social Care Information Centre [HSCIC], 2013).

Everyone using the National Health Service (NHS) should expect that their medical information is treated in confidence and that they can speak openly about their health knowing that it will not be disclosed (HSCIC, 2013). We need to acknowledge however, the differing individual views and expectations around confidentiality amongst service users. One study that looked at the meaning of confidentiality found that whilst patients share an understanding that confidentiality is protection of information, there were differing views on what medical information was classed as confidential and when this information could be shared (Jenkins et al, 2005). Though a small qualitative study of 85 women in one urban region of America, it does highlight an important issue around levels of service-user knowledge and expectations.

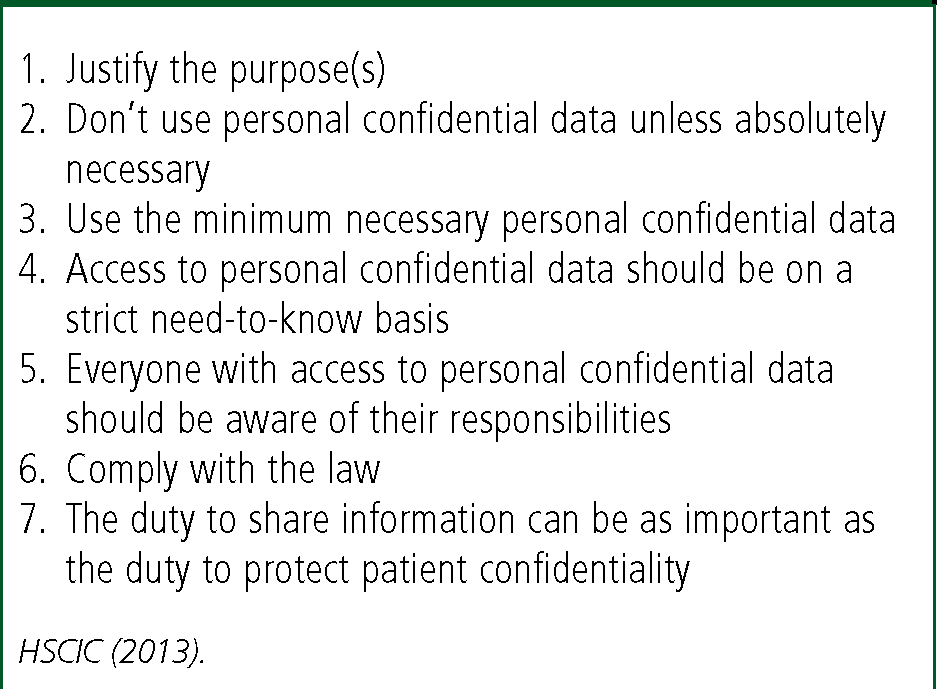

The legal framework governing the use of personal confidential data in healthcare includes the NHS Act 2006, the Health and Social Care Act 2012, the Data Protection Act 1998 and the Human Rights Act 1998 (NHS England, 2015). The Data Protection Act is the key legislation covering all aspects of information processing, which includes the security and confidentiality of personal information and requires that patients are informed of how their information may be used. Seven Caldicott principles provide the framework to put the Data Protection Act into operation which paramedics should be aware of (Figure 1).

We know that patients have the right to object to information they provide in confidence being disclosed to a third party in a form that identifies them (Department of Health [DoH], 2003) even if the reasons are bizarre, irrational or non-existent and even if their refusal will result in their death (Jackson, 2013) but there are exceptions and these will be discussed.

Professional perspective

An ability to account for our actions with a clear evidence base is a crucial component of professional accountability (Gallagher and Hodge, 2012) and reflected in a healthcare professional's code of conduct. Caulfield (2005) describes the four pillars of accountability as being ethical, legal, professional and employment. Failure to practise within the framework of the law could result in potential repercussions such as dismissal or a loss of right to practice (Gallagher and Hodge, 2012).

Patients have a right to privacy and confidentiality (Jackson, 2013) and the HCPC state that paramedics should not compromise the professional/patient relationship (HCPC, 2012a). Jenkins et al (2005) highlight that research conducted in several countries suggests that people are more likely to seek medical treatment and speak openly if privacy is respected. It is important to acknowledge however, that there are occasions in clinical practice where there may be stronger ethical or legal justifications for putting this relationship at risk and that it is not always possible to uphold such an ‘ethical rule’ (Newman and Hawley, 2007). Jones (2003) sent a questionnaire based assessment to 30 consecutive patients attending a GP surgery evaluating the importance patients place on medical confidentiality. The participants felt that whilst they valued confidentiality and would not withhold information other patients might be deterred from seeking medical treatment if their confidentiality was not respected. Some thought that this might be a price worth paying if others were protected from harm however.

The HCPC Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics state that registrants ‘must act in the best interest of the service users’ and ‘only use information about the service user to…continue care for that person or for purposes where that person has given you permission to use the information or the law allows you to do so’ (HCPC, 2012a).

Where information is disclosed, we are obliged to work within data protection laws and follow best practice for handling confidential information (HCPC, 2012b). It is important that paramedics ‘make their own informed decisions about disclosure and be able to justify them’ (HCPC, 2012b), so it is crucial that issues of potential disclosure are discussed with colleagues and balanced with the rights of the individual, the rights of other affected persons, the risk of compromising the patient clinician relationship and the loss of confidence in wider NHS services (DoH, 2010). Where circumstances dictate that confidentiality be breached, Colliety and Horton (2012) advise that it is essential that action is taken and that this is communicated clearly to the patient detailing the standards of, and exceptions to, confidentiality in order to maintain the professional and trusting professional/patient relationship.

Ethical perspective

The utilitarian perspective that the maintenance of confidences by healthcare professionals encourages patients to seek early medical help and contributes to the maintenance of a healthy society (Harris, 1985) has already been alluded to. This outcome causes the most benefit and least harm for most people (Gallagher and Hodge, 2012). Such views compete with the rights based theories that value the patient's rights to privacy and confidentiality. In this paradigm patients have ‘positive’ rights that require something of others and ‘negative’ rights where people are left alone without interference (Gallagher and Hodge, 2012).

Beauchamp and Childress (2009) describe a popular ethical framework known as the four principle approach, which considers the patient's right for autonomy (their right to hold views and make choices), the principle of non-maleficence (not inflicting harm on others), the principle of beneficence (doing good) and the principle of justice which involves a judgement on fairness and entitlement. There are many competing issues of beneficence and non-maleficence when potential or actual harm to the patient and the public is considered and so this can prove limiting. Interestingly, this framework has been criticised for being too simplistic and should therefore be approached critically and thoughtfully (Gallagher and Hodge, 2012).

From a consequentialist perspective, if a patient felt that they could not trust the paramedic to keep information confidential they may be reluctant to disclose information or authorise necessary tests as part of an examination (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009). The paramedic however, could use a consequentialist argument to support an exception to the rule of confidentiality when there may be substantial threats to others, to public interest or the patient (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009).

Legal perspective

We have a duty to share confidential information in the best interests of a patient in their direct care if it results in better or safer care (HSCIC, 2013). There are some statutory provisions whereby information should be kept confidential such as the Data Protection Act 1998, which governs the storage of personal information and provides protection to patients relating to privacy recognised in human rights law by Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, whilst others deal with specific areas like healthcare (DoH, 2003; Montgomery, 2003).

From a legal perspective, in both civil law and criminal law, a person has a right to exercise choice in relation to personal and bodily integrity, and to have that choice respected (Gallagher and Hodge, 2012) but Jackson (2013) acknowledges that the right to refuse treatment ignores the impact on other people increasing the legal and ethical tension.

Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001 makes it lawful to disclose confidential information in specific circumstances where it is not practicable to satisfy common law confidentiality obligations (Health and Social Care Act, 2012). However, the Data Protection Act continues to apply. Disclosure of information under the Data Protection Act still requires consent unless the justification for disclosure is identified in schedule 3 that includes ‘administration of justice’ and ‘vital interests’ (Data Protection Act, 1998).

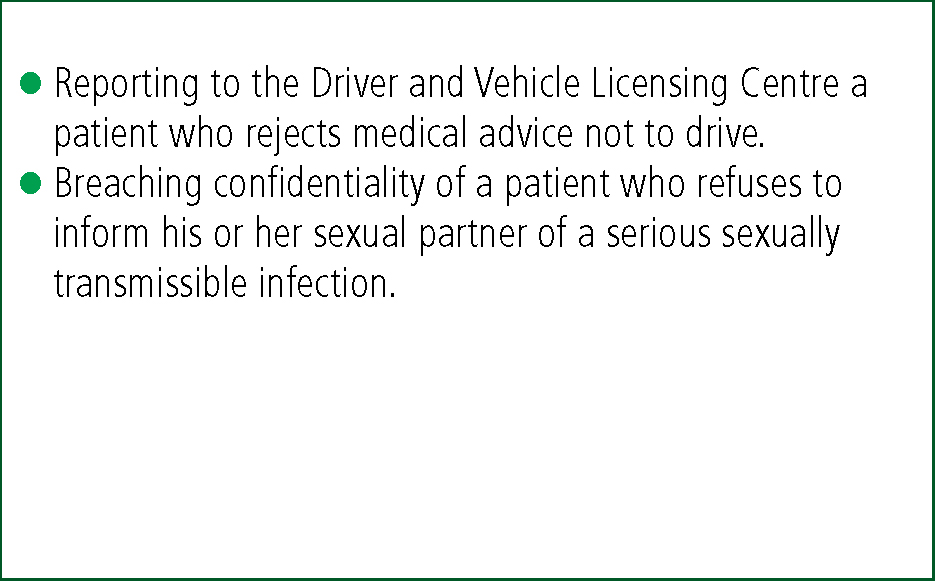

The common law of confidentiality is built up from case law over many years and is often open to interpretation (DoH, 2003). Whilst confidential information cannot be disclosed to prevent harm to an individual, case law has established that confidentiality can be breached where there is overriding public interest that includes the prevention, investigation and punishment of serious crime and to prevent serious harm or abuse to others although it is recommended that this is discussed with the patient where possible (DoH, 2010). ‘Serious crime’ is not clearly defined in law and so crimes such as theft, fraud or damage to property may not warrant breaching confidentiality. It is important to note that disclosure in the public interest is quite different from the specific statutory requirements for disclosure in relation to crime, which would include the names of patients treated as a result of a road traffic collision to assist in an investigation (DoH, 2010). Examples of where public interest can be a defence are highlighted in Figure 2.

Obligations to divulge confidential information most commonly occur when a patient or other third person faces serious danger, and in making our judgement as to whether or not the situation justifies a breach in confidentiality, we must balance the probability and extent of the harm with the obligation of confidentiality. This can be difficult to put into practice (Beauchamp and Childress, 2009; Jackson, 2013). The strength of the obligation relates more to the underpinning moral and practical arguments relating to the professional code of ethics rather than formal recognition in law and the more sensitive the information the stronger the competing arguments need to be (Montgomery, 2003).

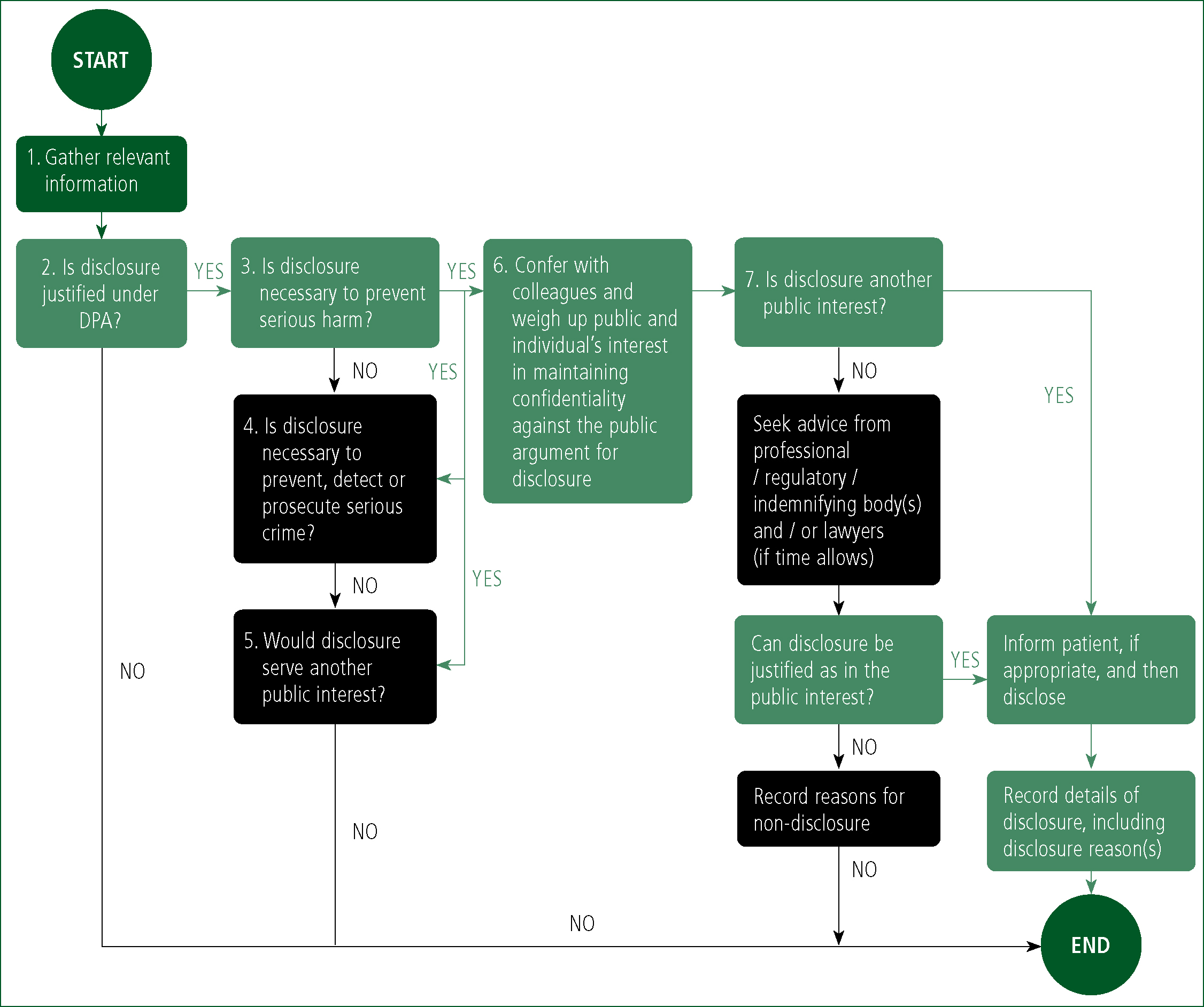

It is considered ethical and lawful to breach confidentiality without a patient's consent when it is in their interest or it is in the public interest to do so (DoH, 2003; Gallagher and Hodge, 2012; Mason and Laurie, 2013), but every effort must be made to persuade the patient to give consent (Mason and Laurie, 2013). A useful flowchart highlighting when a disclosure of confidential patient information without consent might be justified in the public interest can be found in Figure 3 and a case from practice is presented in Box 1.

Conclusion

A paramedic, like any other healthcare professional, is required to act in accordance with their code of conduct and standards of performance. They must be responsible for their actions.

Whilst there is an imperative to preserve the professional/patient relationship, there are occasions where this is not possible. Patients have a right to privacy, and that any information disclosed within a professional interaction be treated in confidence but privacy and confidentiality are not the same thing and will be viewed differently in law.

In general, the confidence of an autonomous person who does not consent to disclosure of information must not be breached, but this duty of confidentiality is not an absolute one. Information can be shared where there is a risk of serious harm to others under the ‘public interest’ exception. If there is a reasonable fear that a person may be physically harmed by the actions of another, then there would be justification to breach confidentiality.

It is important then to consider the ethical, legal and professional basis of all clinical decisions relating to patient confidentiality, and seek advice from senior colleagues or your employer as necessary when there is a risk to the patient or others in order to make the best decisions.