Staff working in emergency response services or frontline healthcare and emergency responders (ERs) have to cope with significant challenges while performing their day-to-day duties. This is the case whether they are patient facing or within an emergency operations centre (EOC) providing telephone triage and advice.

Their actions and decisions often have a direct impact on patient care and they will potentially bear witness to these outcomes, positive or negative. They will inevitably be exposed to the varied emotional responses of the patients themselves, as well as of family or friends.

These ER staff face issues daily, which are multifaceted and can raise stress levels. The resultant stress reactions are a normal response and often quickly subside; however, there are occasions where symptoms persist and no longer remain sub-clinical (Khan et al, 2020). This persistent occupational stress can result in a variety of mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety and, on occasion, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (King's College London, 2020).

A UK study on ER mental health conducted by Mind (2019) delivered some stark messages: ERs were twice as likely to attribute their mental health symptoms to their occupation than the general population, with 27% contemplating taking their own life because of work stress and poor mental health. Bennett et al (2005) provide further insight by suggesting it is not just highly stressful incidents that cause the problem; additional workplace stressors such as growing workloads, tension with colleagues and an increase in social accountability, add to these.

These findings were also reported in an Australian study conducted by mental health advocacy group Beyond Blue (2018). This surveyed 21 014 emergency services personnel, and the findings demonstrated a significant difference between the ERs and the general public. Of the ERs, 39% reported having been diagnosed with a mental health condition compared to 20% of the general public, and suicidal thoughts were twice as common among the ERs, with three times as many stating they had made specific suicidal plans (Beyond Blue, 2018).

A variety of studies have been conducted across the globe and the evidence is broadly homogenous; ERs share common difficulties which can negatively affect their mental health, which are compounded by workload and an increased focus on performance (Davidson et al, 2021).

Trauma risk management (TRiM)

To be a successful ambulance service and deliver the highest level of clinical care, organisations must put the health and wellbeing of their employees at the centre of their core values (Meadley et al, 2020). Employing organisations are now making strides regarding the support they provide. Organisational decision-makers are the first to be able to make a positive difference by choosing the most appropriate and evidenced-based support system available. Unfortunately, some organisations still incorporate single debrief sessions or mandated group debrief sessions, although there is little or no evidence supporting their use (Rose et al, 2002; Smith and Roberts, 2003).

While it is accepted that no one system will provide all the support required for every employee, having supportive first-line managers who are down to earth, approachable and able to foster supportive relationships across their teams, and encouraging access to local evidence-based support systems, such as trauma risk management (TRiM), can help (Lewis et al, 2014; Brooks et al, 2015).

The requirement for visible and accessible organisational leaders, the need to normalise psychological reactions that are commonly experienced by ERs and having established peer support systems are all highlighted in recent British Psychological Society (2020) guidance.

TRiM is a peer-led system that provides individuals who have completed a recognised 2-day training course with the ability to deliver a TRiM assessment. The TRiM assessment is a screening tool used to identify whether an individual is displaying signs or symptoms of acute stress, and whether these signs persist for an extended period of time or subside and disappear.

To become a TRiM practitioner (TP) one must initially express an interest in supporting colleagues and attend a training course. While some organisations mandate this training, the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) (Lakey et al, 2018) suggests that those who volunteer are more likely to take on a sense of responsibility and believe in the system.

The training course covers how traumatic events affect an individual, how the brain functions when experiencing stress, physical signs and symptoms that may occur, how to safely conduct a TRiM assessment and the provision of follow-up advice on recovery, including how to access professional counselling if necessary.

The methods adhere to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2018) guidance for post-traumatic stress disorder, which advocates active monitoring and encouraging access to peer support.

There is no intention to provide psychological treatment within TRiM—the intention is to establish whether risk factors are present that remain or worsen over a month following a potentially traumatic incident and refer appropriately. The TP also provides information on recovery such as on nutrition, sleep and exercise and, if necessary, will support the individual to access professional counselling services.

Two assessments are conducted, which should be 1 month apart. This allows time for the individual to recover without over-treating for acute stress symptoms. Throughout this month the individual is monitored and supported by peers with or without organisational support as required; this is the active monitoring as referred to in the NICE guidance for post-traumatic stress disorder (NICE, 2018).

The ethos and principles of TRiM should be wider than just delivering an assessment. A more holistic approach is advocated, which should include providing general wellbeing advice covering nutrition, sleep and self-help strategies. There should be an opportunity for the individual being assessed to access wider health and wellbeing services should counselling not be required.

The TP is able to provide peer support that can encompass: signposting the person for further help; offering general support; making people feel that they are cared about; taking control of mental wellbeing; and supporting access to counselling services should they be required (Creamer, 2012).

TRiM implementation

In 2015, the North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust implemented TRiM as a trial across two geographical sectors; this covered approximately 450 employees. At the time, there was no in-house support service available for staff; self-referral through occupational health was the only way to access professional counselling.

Informal sharing of emotions and memories with colleagues following a potentially difficult incident can help promote recovery (Pasciak and Kelley, 2013; Appalachian Search and Rescue (ASR), 2015). The self-referral route for counselling automatically poses a barrier for ERs to seek help as they are often reluctant to seek support for symptoms related to mental health and wellbeing (Mind, 2019).

When investigating stress among ERs, Clompus and Albarran (2016) found they relied heavily on peer support networks. Further to this, ERs are more likely to engage with systems that provide evidence-based information around resilience, which increases their own self-awareness, thus building their own resilience (Ledesma, 2014).

Alternative systems were considered such as critical incident debriefing; however, there is growing evidence to suggest that intensive sharing of emotions in a group setting, sometimes referred to as psychological debriefing, might not be helpful and in some circumstances can be harmful (Pasciak and Kelley, 2013; ASR, 2015).

The informality of TRiM encourages a more relaxed approach, which is often seen as a chat delivered by someone with shared experiences who has some knowledge of the individual they are assessing (Evans et al, 2013; Sattler et al, 2014). This is opposed to support being delivered by managers/leaders, who may take a more formal approach yet have little training or experience in providing health and wellbeing support (Lewis et al, 2014).

Implementation began by recruiting 40 individuals, all of whom volunteered for the role. They represented a cross-section of frontline clinical roles, including emergency medical technicians, paramedics, senior paramedics and advanced paramedics. The rationale for this cross-sectional recruitment was to provide diversity to ensure assessments were delivered peer-to-peer, as it was recognised that people need to understand and identify with an individual's experiences to be able to deliver efficient peer support (Balogun-Mwangi et al, 2019).

All volunteers attended a 2-day TRiM practitioner course run by a recognised provider. The individuals were termed TRiM assessors although most organisations use the TP title. This decision was made to avoid confusion arising from using the ‘practitioner’ term in a clinical workforce. This article will continue to refer to those delivering assessments as TPs.

A simple email referral system was developed with nominated coordinators sending out TRiM offers. The local management teams and EOC would highlight potentially traumatic incidents and identify those involved. If staff involved accepted an offer of help, a TP would be sourced and an assessment completed. The TP would then either follow up in 1 month's time or make a referral to the counselling services if this was deemed necessary.

Participation was voluntary as was the acceptance of any counselling recommendation. The whole system was confidential and no records were kept of the assessment itself. This element was crucial and has been shown to encourage openness and a non-judgmental environment to speak freely (Lewis et al, 2014). The local leadership and management teams were informed that the TRiM team had picked up a referral but no further details were disclosed. Confidentiality is crucial to TRiM as this is a recognised barrier to accessing support—the fear of colleagues or managers finding out can deter individuals who are experiencing acute stress symptoms from getting support (Fielding et al, 2018).

Over the following 2 years, TRiM was rolled out across the entire trust. Assessments were made available to all ERs, including personnel within the three EOCs and those providing a face-to-face response. A conscious effort was made to recruit TPs from a range of job roles to ensure peer support could be made widely available.

A structure was developed to allow timely offers to be sent out to individuals who had been exposed to potentially traumatic incidents. They were then able to access a TP of their choice at a location convenient to them and provided with the appropriate assessment.

It has taken a number of years to embed the process, including the creation of robust policies and procedures, drawing up a memorandum of understanding, delivering the 2-day TRiM practitioner course in-house, and establishing the TRiM coordinator role. Attending the 2-day course allows individuals to reflect on their own health and wellbeing, and develop self-awareness of their own vulnerabilities. Evidence-based research has shown that resilience is a learnable and multi-dimensional trait that can be gained in a traditional classroom environment; such teaching sessions increase the level of resilience (Gunderson et al, 2014).

Evaluation

It is difficult to identify the nature of incidents that are likely to cause acute traumatic stress symptoms or PTSD in the longer term. There are categories of incidents that are associated with the development of PTSD, including experiencing or witnessing serious accidents, physical and sexual assaults, various forms of abuse and work-related exposure to trauma (NICE, 2018).

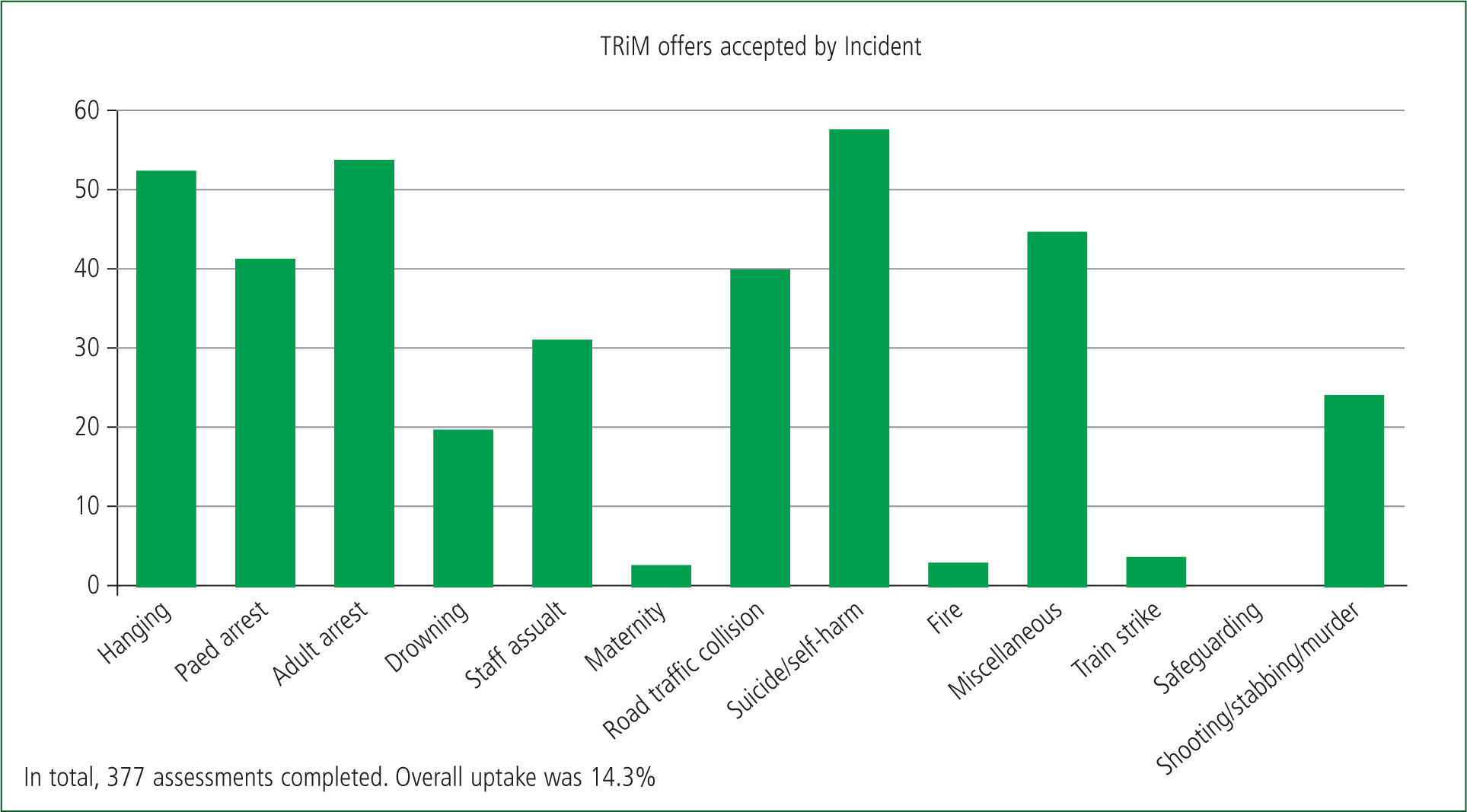

Figure 1 shows the different categories of calls that generated an offer of a TRiM assessment. This provides an insight into the nature of incidents that first-line managers, EOC staff and ERs suspect may be potentially traumatic.

There is, however, much more complexity to identifying traumatic incidents, which is not considered here. For example, the ER may have known the individual involved in the incident, have attended a number of challenging incidents in a short period of time or have had a personal connection with the type of event. Coupled with this is the personal situation the person may be in; they may be going through financial hardship, divorce or having problems with their own physical health, all of which will have an impact on how they manage work-related stress (Thomsen et al, 2023). This list is not exhaustive and a plethora of components influence how an incident will affect an individual.

If an organisation has first-line mangers who are familiar with the employees' characteristics, they are better placed to predict if an incident is likely to cause acute stress symptoms. There is strong evidence to suggest that previous exposure to similar incidents or life experiences will increase the chances of a person developing acute stress symptoms (PTSD UK, 2023). This would suggest that managers would be more effective at identifying potentially traumatic incidents if they were familiar with the staff they support in terms of both their professional experiences and their personal situations.

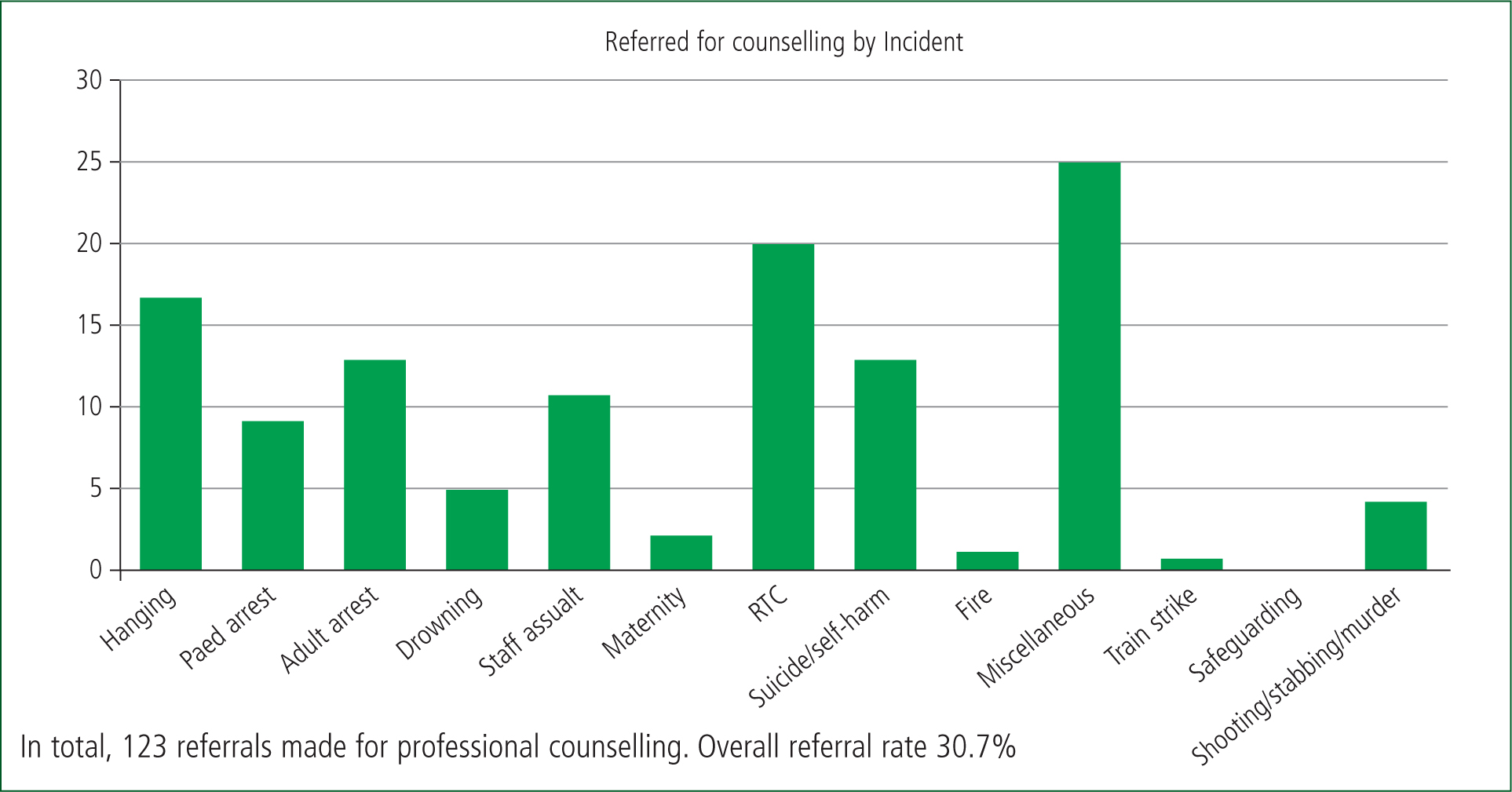

Figure 2 gives an insight into the categories of incidents that generated an assessment. As discussed, TRiM offers are sent out with little rationale other than anecdotal evidence that certain categories of incidents are suspected to be more difficult to manage. There is a correlation between the type of incident, which offers are sent out and the uptake of assessments, with cardiac arrest related-incidents and road traffic collisions being the categories in which most offers are sent out and the highest number of assessments are carried out. The standout incident type, which also generated a high number of assessments, is suicide/self-harm-related incidents. This provides insight into the types of incidents on which TRiM coordinators may focus in future.

As previously mentioned, the majority of people manage acute stress with no need for direct support or intervention, with symptoms usually subsiding within a short period of time (Patient.info, 2023). This is clear by the relatively low number of staff accessing TRiM assessments in comparison to the number of offers sent out. There was an intention to send out an offer of an assessment for any potentially difficult incident, and it was acknowledged that the majority of staff would not require an assessment. The rationale was to initially cast the net wide to reach any member of staff who might require the assessment.

Figure 3 supports the theory that cardiac arrest-related incidents and road traffic collisions not only generate more assessments, but also lead to an individual accessing professional counselling services. There is some evidence to suggest that the relatively high number of paediatric referrals is due to the vulnerability and innocence of paediatric patients. This can prompt a more intense response around blame and shame, as the ER passionately wants to achieve a positive outcome for the patient, despite this not always being possible (Vasset et al, 2019). The Manchester Evening News (MEN) Arena terrorist attack was analysed separately, and resulted in a 20% uptake of offers of an assessment with a 38% referral rate for professional counselling services. It is unsurprising that this generated a higher number of both assessments and referrals to counselling services compared with commonly attended incidents. It is recognised that human-made disasters causing a major incident have a higher likelihood of causing both acute and chronic stress (Ursano et al, 2017).

Four testimonials (Appendix 1, online) were selected for inclusion in this study as they demonstrated individual responses from those who accessed TRiM. These are overwhelmingly positive about the process. There has been one common negative issue raised within the first year of implementation; this concerns multiple TRiM offers being sent out from different individuals. The process of coordination was amended following this feedback, and the issue was also included in the 2-day TP course to ensure clarity around the procedure. No issues have been raised since.

Conclusion

A key advantage of adopting a system driven by peer support is to encourage ERs to seek help as they are less likely to independently access psychological support, such as counselling (Lawn et al, 2020). Engaging in a recognised peer support intervention can promote recovery from acute stress, which in turn improves organisational efficiency by providing a cost-effective and easy-to-implement intervention. The correct system can also be linked to and complement professional counselling services.

The informality of the TRiM assessment can increase engagement and increase the likelihood of the early signs of PTSD being identified. This allows the individual to access professional, targeted support facilitated by the organisation, aligning with the aims of the workforce Health and Wellbeing Framework (NHS Employers, 2021) and the recommendations of the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (2019). This is coupled with allowing the majority of ERs experiencing no long-term negative effects the time to process the incident and recover without intervention. The whole process aligns with NICE (2018) guidance for PTSD by avoiding offering psychologically focused debriefing to prevent PTSD and adhering to the following:

In addition, the second assessment allows active monitoring over a period of 1 month and beyond if necessary (NICE, 2018).

Evidence suggests that organisations that implement a successful peer-delivered support system that encourages staff engagement, such as TRiM, can expect to see a positive effect on employee health and wellbeing, which in turn will improve the quality of services and patient satisfaction (Ogbonnaya and Valizade, 2018). This can ultimately result in positive outcomes for the employee, organisation and patient (McDaid, 2011).

While there is overwhelming evidence that acute stress can cause mental health problems, it should be recognised that distress and suffering are not psychopathology. PTSD has been talked about a great deal and over the past 5–10 years as mental health conversations have been encouraged; nonetheless, surviving traumatic stress can result in positive outcomes (Beyond Blue, 2018). Within the TRiM assessor's course, post-traumatic growth is recognised and discussed to raise awareness that exposure to a traumatic event can result in positive outcomes because of a development in one's appreciation of life (Halpern et al, 2012).

It should be recognised that the majority of individuals will not develop PTSD and will recover from any short-term symptoms without any formal interventions. The TRiM assessment highlights this to the individual and avoids over-treatment of post-incident distress.

Research also suggests that perceived support has a positive effect on individuals, and knowing that the organisation has invested in an evidence-based support system that is available should they require it is in itself helpful (Osório et al, 2013). It is clear that peer-led support, delivered locally, can be helpful (Khesroh et al, 2022). It is crucial that such a system is implemented correctly, as this can have a direct impact on the success and longevity of the process (Khesroh et al, 2022). An organisation requires the system to be supported and led correctly; otherwise it is likely to fail.

The fact that a workforce of the largest (geographically) ambulance service in England has had growing engagement with TRiM over a period of 6 years suggests the process has been implemented correctly. The continued use of TRiM by the workforce, including coordination by the TPs, acceptance of assessments and onward referral to counselling services demonstrates a positive outcome for the individuals accessing the process. This is supported by the testimonials of those who have engaged with the process at different levels.