Legal highs are becoming increasingly popular within the UK population, resulting in increased public morbidity, mortality and strain on the NHS. The number of admissions and exact cost to the NHS is unknown, but since 2009 deaths definitively associated with ‘legal highs’ had risen to 97 in 2012, with statistics expecting to rise further (BBC, 2015). These products have multiple terms, but for this proposal bath salts, new psychoactive substances, designer drugs, plant food, and party drugs will be known under the umbrella term of ‘legal highs’. ‘Legal highs’ are widely available and often marked as: ‘not for human consumption’ (Gibbons, 2012). However, despite the warnings, members of the public continue to consume these chemicals for leisure and the psychoactive effects they induce (Ratnapalan, 2013).

This proposal is to introduce a pre-hospital referenced ‘legal high’ guide (LHG) to clinicians in order to educate staff and improve patient care quality through the instigation of a paperback pocket guide or downloadable application for smartphone and tablet technologies.

Previous literature

‘Legal highs’ were highlighted by the media after suspected deaths across several countries were associated with the use of mephedrone (also known as ‘meow meow’ or M-CAT), with 70 in the UK. The highlighted risks of mephedrone led to its ban and other closely related derivatives in 2010 (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, 2010; Ratnapalan, 2013).

Thousands of legal highs are purchasable on the internet, with Ratnapalan (2013) reporting 39 websites selling 1 308 affordable products at less than £10. Multiple studies (Brandt et al, 2010; Ramsey et al, 2010; Ayres and Bond, 2012; Shanks et al, 2012) have found that products purchased have inconsistent contents or concentrations between the same products. Ayres and Bond (2012) found dangerous drugs such as mephedrone—despite the UK Home Office ban (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, 2010)—in products not advertised correctly, with the public inadvertently breaking the law and putting themselves at risk.

Ayres and Bond (2012) found that imposition of legislation banning chemical compounds in ‘legal high’ products has led to chemists modifying molecular products in order to evade the law. Ayres and Bond (2012) hypothesise that this could lead to the creation of more dangerous counterparts being released to the public with unknown implications, drug contraindications and antidotes. These legislations could lead to detriments in public health through the consumption of these new chemicals.

Illicit drugs such as cocaine, the newly banned cathinone mephedrone and its associated compounds have often been found ‘cut’ or contaminating the intended substance. Baron et al (2011) and Dargan et al (2011) found cathinones in ‘legal highs’ despite the Misuse of Drugs (Amendment No.2) (England, Wales and Scotland) Regulation 2015 (S.I. 2015/891). Ayres and Bond (2012) stipulate that this is not merely indicative of the retailers' attempt to sell off surplus stockpiles of mephedrone, but are still being intentionally sold over the internet.

‘Legal’ alternatives to illegal drugs have generic classifications owing to their main advertised effect (stimulants, downers and hallucinogenics). Stimulants, such as synthetic cathinones (Bubbles, M-CAT, Impact Energy-1, NRG-1) causing euphoria, heightened alertness, increased energy, talkativeness, increased sexual arousal, as well as sympathomimetic toxicity with tachycardia, hypertension, hyperthermia, dehydration, psychosis and insomnia (James et al, 2010; Winstock et al, 2011; Rosenbaum et al, 2012). Downers such as synthetic cannabinoids (Spice Gold, Spice Silver, Genie, K2) produce similar effects to marijuana when smoked. Effects include: tachycardia, hypertension, palpitations, diaphoresis, anxiety, agitation, seizures, arrhythmias and hallucinations (Müller et al, 2010; Vearrier and Osterhoudt, 2010; Johnson et al, 2011a; Schneir et al, 2011). Hallucinogenics such as salvia divinorum are advertised as a legal alternative to marijuana but have more in common to lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) (Johnson et al, 2011b; Gibbons, 2012). Effects include tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis, confusion and hallucinations (Babu et al, 2008).

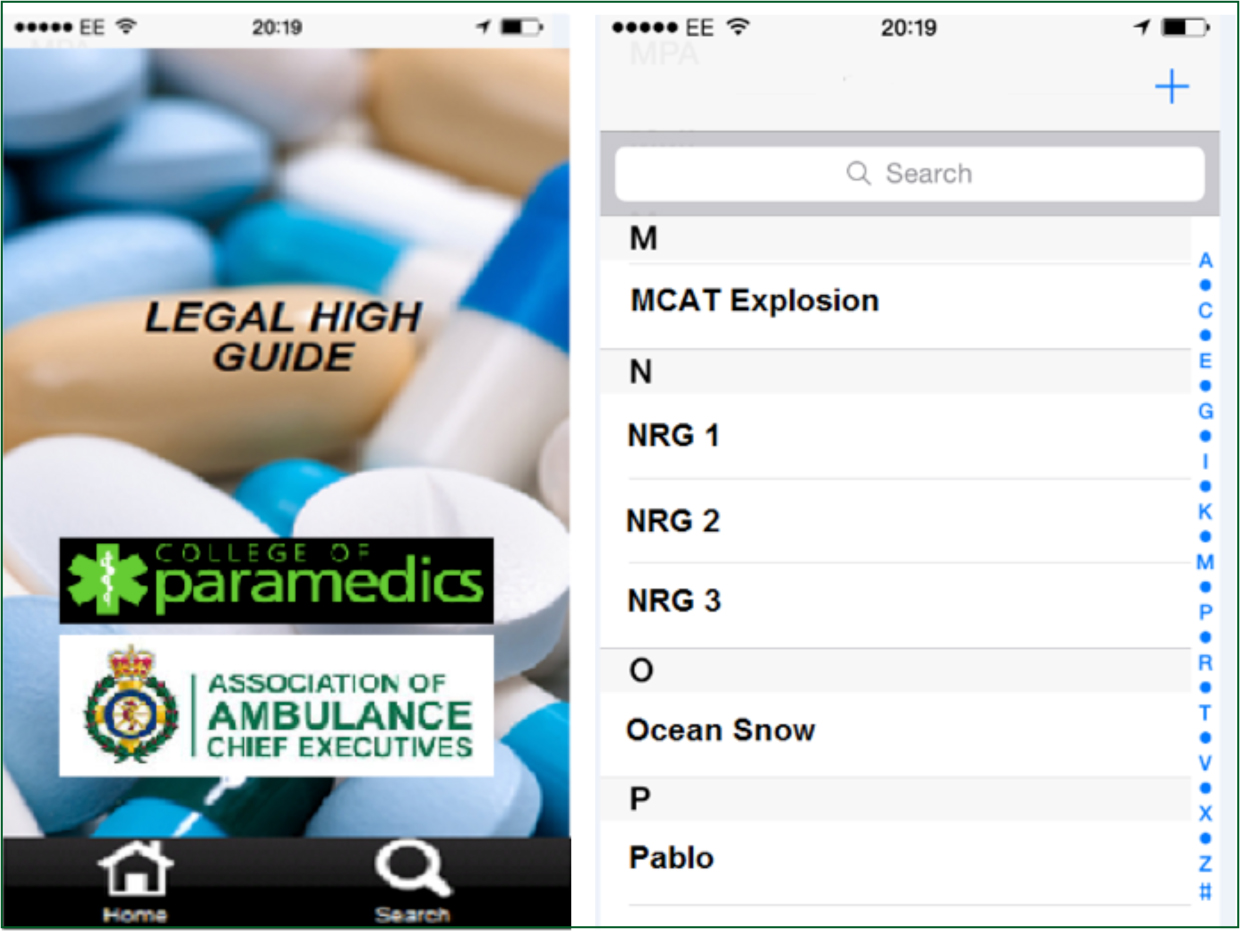

Franko and Tirrell (2012) found that downloadable medical applications are becoming increasingly popular among the healthcare profession. However, application use can be dangerous due to lack of approved health authority representation and software malfunctions (Buijink et al, 2013).

Aims/objectives

Pre-hospital clinicians use the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE) (2013) and local NHS Trust guidelines for patient care. However, it remains questionable as to how clinicians are supposed to be able to treat what they are unable to understand or correctly identify when product data is inconsistent across multiple studies, let alone understand the drug effects (Brandt et al, 2010; Ramsey et al., 2010; Ayres and Bond, 2012; Shanks et al, 2012). Clinicians are not only limited to symptomatic treatment, but due to the lack of research and latent guidelines of polypharmic chemical compound effects on human physiology, these treatments could inadvertently lead to harm.

The aim is to provide a central referenced LHG to improve patient care and pre-hospital education. The guideline will inform clinicians of typical side effects these drugs can cause so that clinicians can more effectively react and plan their management strategies with more confidence. However, due to the varying chemical concentrations of these drugs it is not intended to definitely inform clinicians of approved interventions.

Method

To create a cited and referenced source for ‘legal highs’ and their typical known side effects approved by the AACE and in partnership with the College of Paramedics for pre-hospital practice. The source will be created using approved reference sources from recent studies looking at the content of legal highs and the effects these chemicals have on human physiology. This source will also provide some special circumstantial time-critical pathologies for some of the ‘legal highs’.

The product will be produced as a smart phone or tablet application, or for clinicians without this technology, a paperback pocket guide. The guideline will be an alphabetised, four category, colour coded product. Table 1 shows the generic template, stimulants (red) can be seen in Table 2, downers or sedatives (blue) can be seen in Table 3, hallucinogenics (green) can be seen in Table 4. A final category (black) will cover other drugs. Figure 2 shows the potential app home page and search option template. Appropriate sub headings will also provide relevant information modelled on the AACE (2013) drug information.

| Product Name (Street Name). (Red: Stimulants, Blue: Downers or Sedatives, Green: Hallucinogenics, Black: Other) |

|---|

| NUMBER WITHIN CATEGORY—PRIMARY CHEMICAL—(CHEMICAL CLASSIFICATION) |

|

Presentations

|

|

Administration

|

|

Indications

|

|

Actions

|

|

Cautions

|

|

Side effects

|

| NRG-1 (Rave, NRG-1, Energy1) |

|---|

| 2 NAPHYRONE—(SYMPATHOMIMETIC) |

|

Presentations

|

|

Administration

|

|

Indications

|

|

Actions

|

|

Cautions

|

|

Side effects

|

| Black Mamba (X, Tai High Hawaiian Haze, Spice, Mary Joy, Annihilation, Amsterdam Gold) |

|---|

| 1 TETRAHYDROCANNABINOL (THC)—(SYNTHETIC CANNABINOID/SYMPATHOMIMETIC) |

|

Presentations

|

|

Administration

|

|

Indications

|

|

Actions

|

|

Cautions

|

|

Side effects

|

| Salvia Divinorum (‘Herb of Maria/the Shepherdess/the Virgin’, Salvia, Diviner's Sage, Herbal ecstasy) |

|---|

| 3 SALVINORIN A—(PSYCHOACTIVE DITERPENE) |

|

Presentations

|

|

Administration

|

|

Indications

|

|

Actions

|

| Cautions |

|

Side effects

|

Practical issues and ethical considerations

Ayres and Bond (2012) hypothesised that imposition of legislation banning chemical compounds in legal high products has led to chemists modifying molecular products in order to evade the law. Studies have also shown that products do not typically contain the same chemical compounds or the same concentrations of these compounds (Brandt et al, 2010; Davies et al, 2010; Ramsey et al, 2010; Baron et al, 2011; Ayres and Bond, 2012; Shanks et al, 2012). This means that precise effects cannot be definitive due to the flexible content. The guidelines will be limited in informing clinicians of common chemical compounds consistently found within the products, as well as the specific effects the classification should present due to the inconsistent concentrations found (Brandt et al, 2010; Ramsey et al, 2010; Ayres and Bond, 2012; Shanks et al, 2012). It should also be noted that each product will typically be associated with certain effects that should be provided to the clinicians.

Further research of exact chemical effects in humans still needs to be studied in both the immediate effects and results from long-term use. The guideline should not provide any form of definitive decision-making evidence but provide a baseline for future research and future AACE guidelines. The guideline is intended to inform pre-hospital clinicians as to what could potential occur post-chemical intake physically and in regard to psychomotor effects.

Implications for knowledge/practice

As discussed, the potentially harmful compounds used within commercial ‘legal highs’ is vast, with a large number of side effects and areas of significance still lacking research. This LHG will not be for pre-hospital clinicians to base their practice upon or alter any already established protocols. The guideline is for educating and supporting clinicians as to what could be typical signs and symptoms that have so far been associated with the ‘legal high’ of concern. The result will be that clinicians will better understand the pharmacology, aetiology and be more vigilant with ‘legal high’ patients. The guideline will be the first AACE, College of Paramedics and Trust-approved guide in support of clinicians, with the potential for future research and updating. The aim of this proposal and the instigation of a guideline will lead to improved quality of patient care and outcome, and improve the clinician's levels of confidence and academic knowledge.

NHS clinicians have support systems in place in order to better provide patient care with more specialised practitioner consult. A guideline in place at the clinical hub can provide more specific information and assist clinicians responding to emergency calls. The LHG could also give clinicians more confidence, as well as a legal safety net for non-conveyances. LHGs provided to the clinical hubs, in either format, will allow clinicians not provided with the guide, or owning a smart device, with an easily accessible referenced source.