LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this module the paramedic will be able to:

The use of supplemental oxygen therapy—the administration of oxygen for medicinal purposes—in the prehospital setting can be life-saving in the treatment of hypoxaemia. However, it is often administered liberally in a routine manner and without clinical indication (Eskesen et al, 2018). In cases of hyperoxaemia, oxygen is also known to be associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in acutely ill patients, such as those with stroke, myocardial infarction (MI) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Branson and Johannigman, 2012; Cornet et al, 2013; Stolmeijer et al, 2018).

In acute exacerbations of COPD, the administration of high-flow oxygen is related to longer hospital stays, admission to high-dependency units, acidosis, hypercapnia and mortality (Austin et al, 2010; Ringbaek et al, 2015). According to Austin et al (2010), one in every 14 patients with COPD treated with high-flow oxygen in the prehospital setting will die, although these risks can be reduced by up to 78% if titrated instead. High-flow oxygen is defined by the British Thoracic Society (BTS) as 8–10 litres/minute, while titration refers to tailoring the oxygen dose to suit the patient's needs (O'Driscoll et al, 2008).

While several prehospital emergency guidelines recommend the use of supplemental high-flow oxygen in patients who have had a stroke, the American Heart Association stroke treatment guidelines recommend supplemental oxygen only where required to maintain peripheral oxygen saturation levels above 92% (Powers et al, 2018). A 2017 randomised clinical trial by Roffe et al (2017) concluded that routine, low-dose supplemental oxygen therapy in non-hypoxic patients who had a stroke did not yield any improvement in functional outcome at 90 days.

With regards to MI, in patients with ST elevation but not hypoxaemia, supplemental oxygen has been associated with higher early myocardial injury, a larger infarct size at 6 months and no reduction in symptoms (Khoshnood et al, 2018). A clinical trial by Stub et al (2015) suggested that chest pain scores did not fall when patients were not given supplemental oxygen therapy, and that withholding such treatment was safe in the normoxic patient with an acute MI.

Although formal guidelines have existed for more than a decade, variations in practice continue surrounding the use of supplemental oxygen therapy. Guidelines drawn up by the BTS summarise the requirements for prescribing target oxygen saturation ranges for individual, acutely ill patients and for those at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure (O'Driscoll et al, 2008).

A UK audit to assess the impact of these guidelines was carried out 4 years after they had been published, which showed that oxygen use and prescribing had improved, and uptake of the guidelines had risen from 6% to 83% (Kane et al, 2013). In 2017, the Irish Thoracic Society published national guidelines on the administration of oxygen therapy in acute settings based on the original guidelines drafted by the BTS. These are, however, aimed at health professionals in hospitals—not those in prehospital settings.

The purpose of the present audit was to assess the use of supplemental oxygen therapy within the Irish ambulance service. Practice would then be compared to formal, international BTS guidelines, with a view to improving ambulance crew awareness, future practice and patient safety. The results of this audit may be useful should specific national prehospital guidelines be developed in the future.

Methods and materials

The current study took place between July 2018 and March 2019 and, in total, the authors audited 4944 patient files retrospectively from two major ambulance services in Ireland. All patients who had direct contact with the service were eligible and no restrictions were applied to the pool of participants; patient files were chosen at random by an emergency medical technician from within the time frame specified.

Each patient's paper file was audited manually, and results and findings were inputted and displayed using Microsoft Excel. As this study was a clinical audit, ethical approval was not required and all results were anonymised. In the cases audited, 413 (8.4%) patients received supplemental oxygen therapy. Of these, 14 patients were excluded from the results as they were already on continuous, long-term oxygen therapy.

The remaining 399 (8%) patients were then audited under the following headings: the reason for requiring ambulance transfer; the delivery device used to administer supplemental oxygen; saturation levels before the therapy was administered; and the level of practitioner who administered the treatment. End-tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2) levels are not routinely measured on board Irish ambulances so were not included in this audit.

The results were then screened against formal international guidelines and recommendations were generated for future improvements in practice with a view to re-auditing in the future.

Results

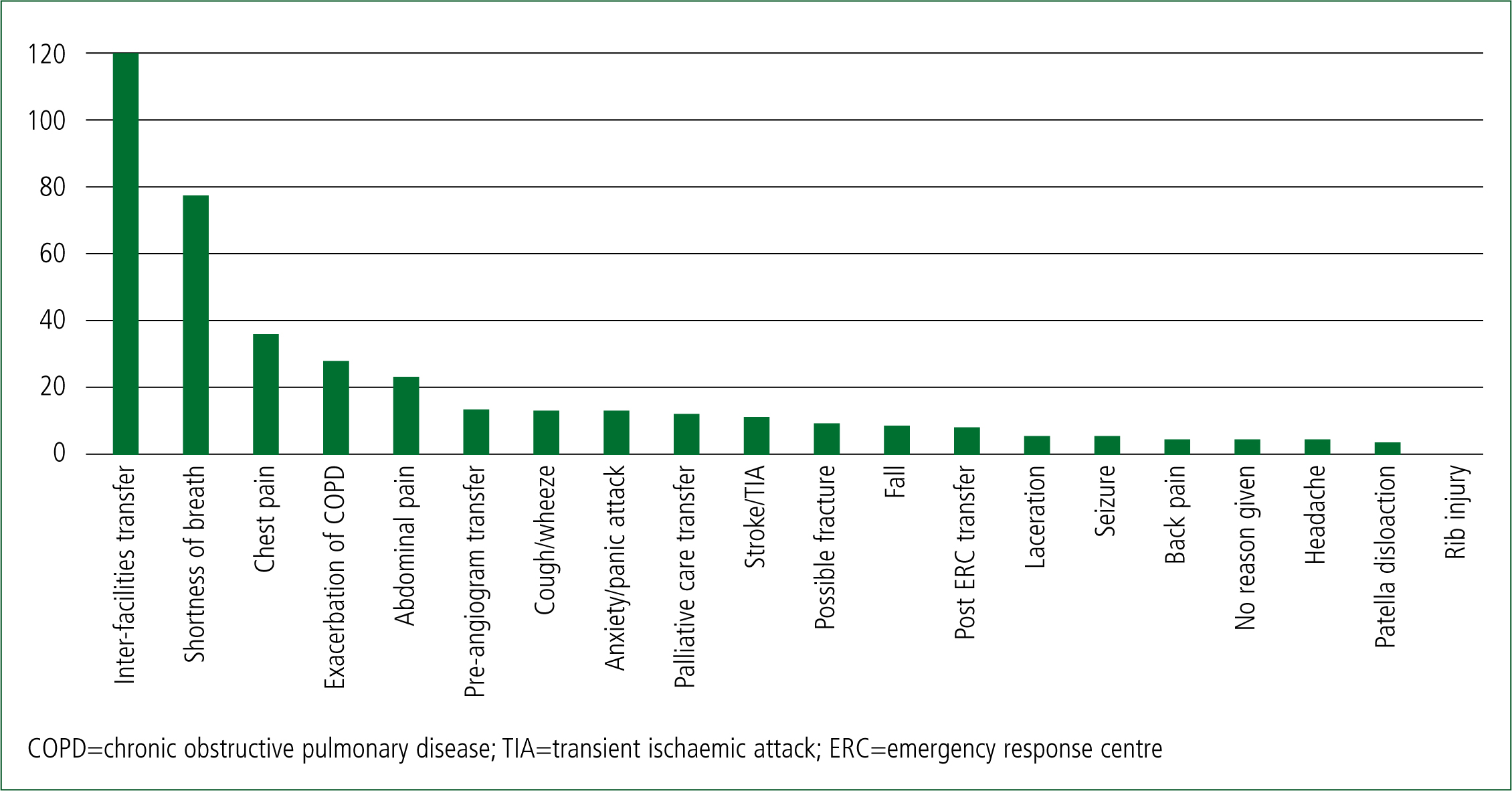

For the 399 patients who received supplemental oxygen, the most common reason for ambulance conveyance was ‘inter facilities transfer’ (Figure 1). This is likely because a private ambulance service was used in this audit.

The international BTS guidelines state that supplemental oxygen therapy is not recommended in prehospital settings unless oxygen saturation levels have fallen below a threshold of 94–98% for most acutely ill patients or 88–92% for patients at risk of type II respiratory failure (O'Driscoll et al, 2008). In the present study, vital sign levels, including oxygen saturations, were recorded before oxygen was administered in 390 (97.7%) patients of the 399 who received it. After oxygen therapy, vital signs were recorded in 100% of patients audited. As mentioned previously, 14 patients were excluded from the results as they were already receiving long-term, continuous oxygen therapy.

This audit found that of the remaining 399 patients who received oxygen, only 16 (4.1%) had saturation levels below the recognised threshold and thus met the criteria for supplemental oxygen. Of these 16 patients, three were experiencing a suspected acute exacerbation of COPD and were therefore at an increased risk of developing hypercapnic respiratory failure if incorrectly treated with oxygen therapy. However, all three patients had oxygen saturation levels below the recognised threshold of 88% so supplemental oxygen had been administered correctly. This study found that supplemental oxygen therapy was being prescribed and administered incorrectly in up to 383 (96%) patients.

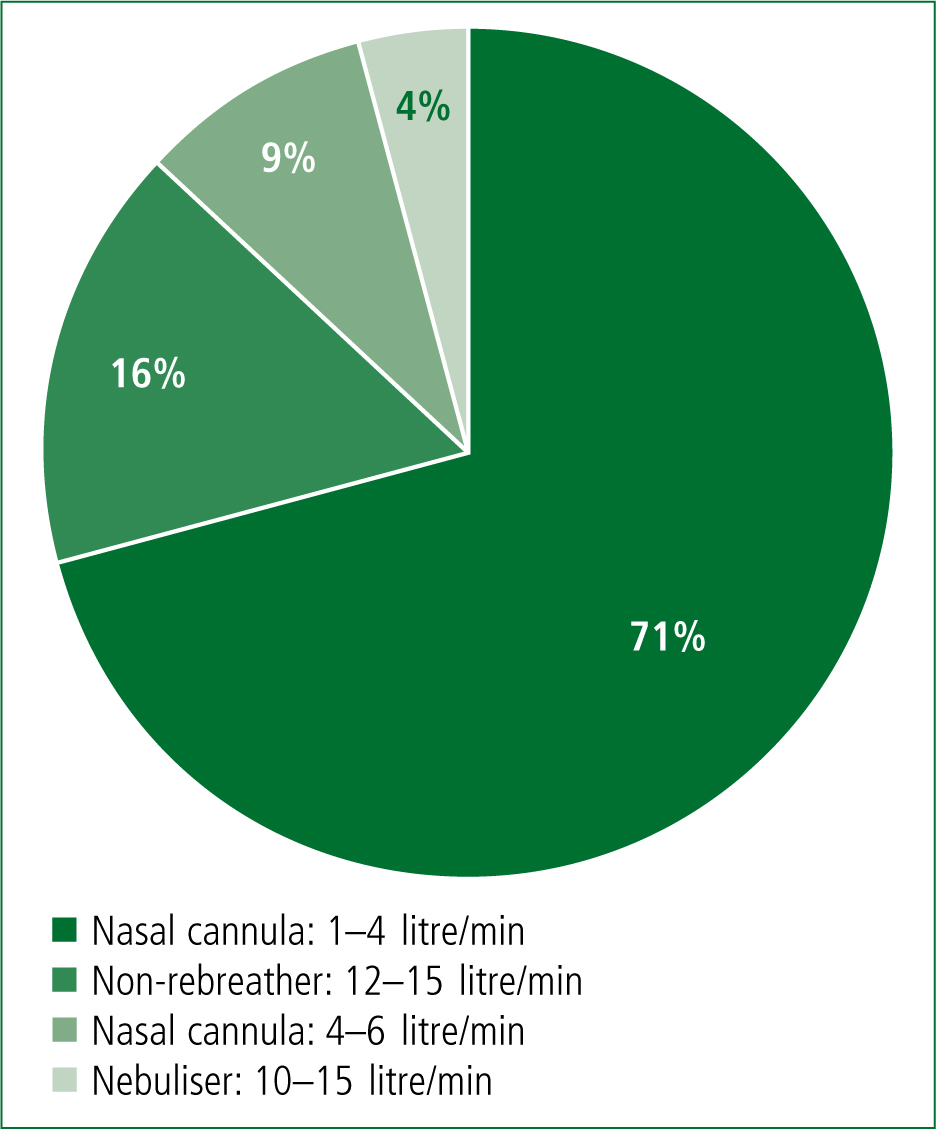

The most common method of supplemental oxygen delivery was via a nasal cannula titrated at 1–4 litres per minute (Figure 2). This method was used on 283 (71%) of the patients audited. It is possible that, where oxygen is being misused, it is mostly likely to be given routinely as low-dose therapy in patients who do not reach the criteria to require it; for example, as a comfort measure. Where higher doses of oxygen are administered via a non-rebreather, the patient could have hypoxaemia and it is likely that the therapy is being used correctly.

The BTS guideline for emergency oxygen use in adults recommends that patients at risk of type II respiratory failure, such as those with COPD, should be administered oxygen therapy where required via a 28% Venturi mask at 4 litres/minute until blood gases can be measured (O'Driscoll et al, 2008). Of the three patients with suspected exacerbation of COPD in this study, all received supplemental oxygen therapy but none had this administered via Venturi masks even though these were available on board.

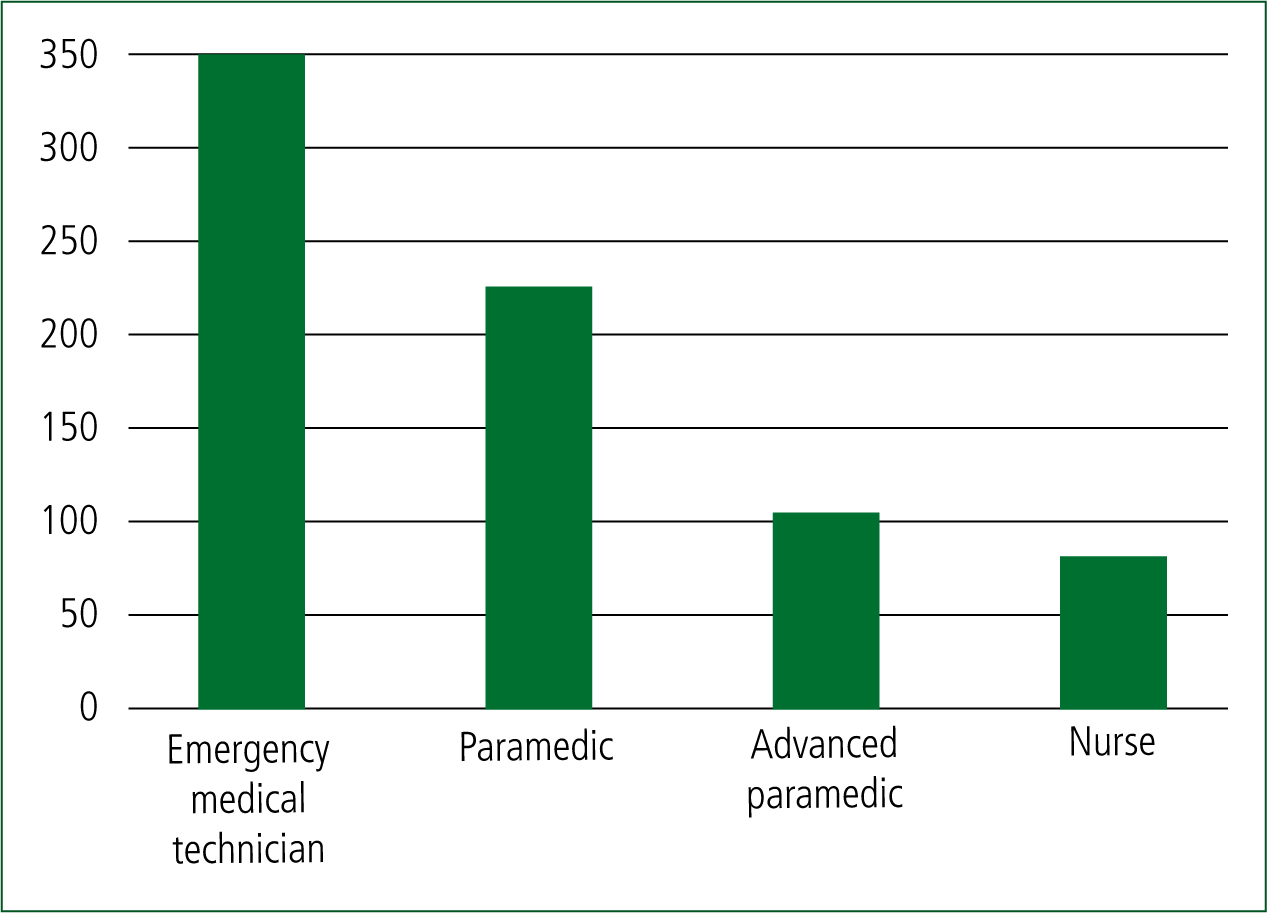

Finally, this audit found that supplemental oxygen therapy is most commonly prescribed and administered by emergency medical technicians (EMTs) in the prehospital setting (Figure 3).

Discussion

This study found that supplemental oxygen therapy was being over-prescribed and therefore misused in 96% (383) of patients, based on current international guidelines.

One possible limitation to these results is with regard to patients having inter-facility transfer, as they used a private ambulance service and, in some cases, the reason for conveyance was not specified.

It is not known how many of the patients moved by private ambulance were already on continuous long-term oxygen. In each case, the initial recording time of vital signs precedes the time documented for starting oxygen therapy. Therefore, the authors have deduced from this information that supplemental oxygen was started in the ambulance even if the patient had an acceptable oxygen saturation level. If these patients were already on continuous long-term oxygen, the oxygen therapy start time should precede the vital sign recording time. In addition, a tick-box option on the transfer documentation to indicate if a patient was on continuous long-term oxygen had been left unchecked for each of the cases in this audit.

The results of this audit indicate that oxygen is most often being misused at lower doses via a nasal cannula. The exact reason for this is not known and was beyond the intended scope of this audit. It does, however, suggest that, taking into account the rest of this study, there is a distinct lack of understanding surrounding the use of and potential dangers associated with supplemental oxygen therapy in the prehospital setting. This lack of awareness among ambulance crews may result in patients being administered low-dose oxygen in the belief that this causes no harm.

According to the present audit, where supplemental oxygen is being administered in the prehospital setting, in 78% of cases, this was done by an EMT. It should be noted that this could be because EMTs attend more calls than other practitioners. This finding suggests that future awareness and education programmes on the safe use of prehospital supplemental oxygen should certainly be targeted at EMTs.

Recommendations and conclusion

The NHS has successfully introduced an oxygen ‘alert card’ system to identify patients who are at a potential risk of or have had a previous episode of carbon dioxide retention, such as those with COPD, cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis or neuromuscular disease, as well as severe cases of asthma (Gooptu et al, 2006; Kane et al, 2013). An alert card is provided to the patient, often along with their own personal Venturi mask, which specifies that, as the patient is at risk of type II respiratory failure, oxygen should be administered only through their Venturi mask; it also states the optimal range of oxygen saturation levels that should be achieved for this patient. These alert cards have proved to be a simple, effective way of reducing the over-prescribing of oxygen in at-risk patients (Gooptu et al, 2013).

Currently, Irish ambulances are stocked only with oxygen-driven nebulisers. During prolonged ambulance transfers in patients with a suspected exacerbation of COPD, repeated nebulisation has the potential to deliver a harmful continuous high concentration of oxygen. Therefore, it is not possible to predict the magnitude of an increase in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pilcher et al, 2013). A further recommendation of this study is that ambulance services could carry alternatives to oxygen-driven nebulisers, such as ultrasonic or air-driven nebulisers, as these allow oxygen to be titrated during use (Pilcher et al, 2013).

Finally, this study recommends further education and awareness campaigns for both emergency service providers and patients at risk of type II respiratory failure. It is evident from this audit and the current literature discussed that there is a continued lack of appreciation and understanding about the dangers of hyperoxaemia. With an increase in training and awareness, it is possible to significantly decrease oxygen-associated adverse events and mortality.