In 2004, a clinical guideline from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended that the evidence supported administration of single-dose activated charcoal (SDAC) within 1 hour of toxin ingestion and that ambulance services were ideally placed to deliver this treatment (NICE, 2004).

A survey the following year (Greene et al, 2005) found that no ambulance services had adopted the treatment, citing concerns which included the lack of a protocol aimed at ambulance staff, increased time on scene, and vomiting by patients with associated ambulance cleaning and increased turnaround times.

A literature review conducted by South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust (SWASFT) in 2012—detailed in a previous article (Walker, 2013)—concluded that sufficient evidence of clinical benefit existed to warrant a trial of SDAC as a treatment within SWASFT.

The primary aim of the trial was to evaluate the feasibility of crews carrying and administering the medication to suitable patients in a pre-hospital setting, in particular examining the concerns raised by ambulance Trusts in the paper by Greene et al (2005). The secondary aim was to describe the patient demographic of those receiving or refusing the treatment offered.

Methods

A Trust-wide retrospective audit of patient clinical records, where the presenting condition code used by the clinician in attendance was deliberate or accidental overdose (excluding alcohol in isolation and intravenous opiate overdose), was undertaken for a sample time period of 6 months in 2011. This identified two geographical zones that accounted for 27% of all such overdoses within the Trust.

These two zones were selected as the trial area and a patient group directive (PGD) (SWASFT, 2012) and brief staff education programme were initiated.

A senior contact in each of the four likely receiving emergency departments (ED) was established for their input into the trial and to act as a liaison point as it progressed.

Regular contact was maintained with paramedic clinicians who had administered SDAC in the two zones to monitor the trial and to answer any emerging questions.

At the end of the trial a search was made for all overdose coded patient records and for those where SDAC was mentioned in the drug administration sections.

This was cross-referenced with information taken from the participating stations' drug stock records to ensure that as many SDAC administrations as possible were captured for analysis.

The PGD specified the patient group as adults and children over the age of 1 year who had ingested a toxin less than one hour before attendance by a paramedic crew, or where Toxbase advised administration outside the 1 hour window. Toxbase had the ability under the PGD to advise administration where a drug that slowed gut motility had been ingested and thus SDAC beyond 1 hour may have been of value.

Patients had to have a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 15 and likely to remain so at least until arrival at ED. Patients who were vomiting or who had likely gut-motility problems were excluded as were a small number of toxins for which SDAC is unsuitable, including petrol distillates, metal salts, alcohol alone in the absence of any co-ingested medication, organophosphates and corrosives.

Patients who had co-ingested alcohol with a medication overdose were permitted to receive SDAC for the medication part of the overdose as long as they were likely to remain with a GCS of 15 en-route to ED in the opinion of the attending clinician.

The charcoal used for the trial was a 50 g dose in a suspension of 250 ml of distilled water. The dose for an adult was the full 50 g, with the paediatric dose half of that unless a large quantity of toxin had been ingested.

Crews were permitted to mix the medication with soft drinks to make it more palatable if necessary. Following administration, all patients were to be conveyed to ED.

An online survey was made available to staff to capture qualitative data and suggestions and views from clinicians.

Results

A total of 691 overdose-coded incidents were identified for the two zones in the trial period, of which 69 were offered SDAC.

Of those not offered the medication, in the majority of occasions this was because the 1-hour window had been missed. Other reasons included a GCS less than 15, unsuitable toxin ingested or uncooperative patient.

94% of patients accepted the offer of SDAC when presented by crews.

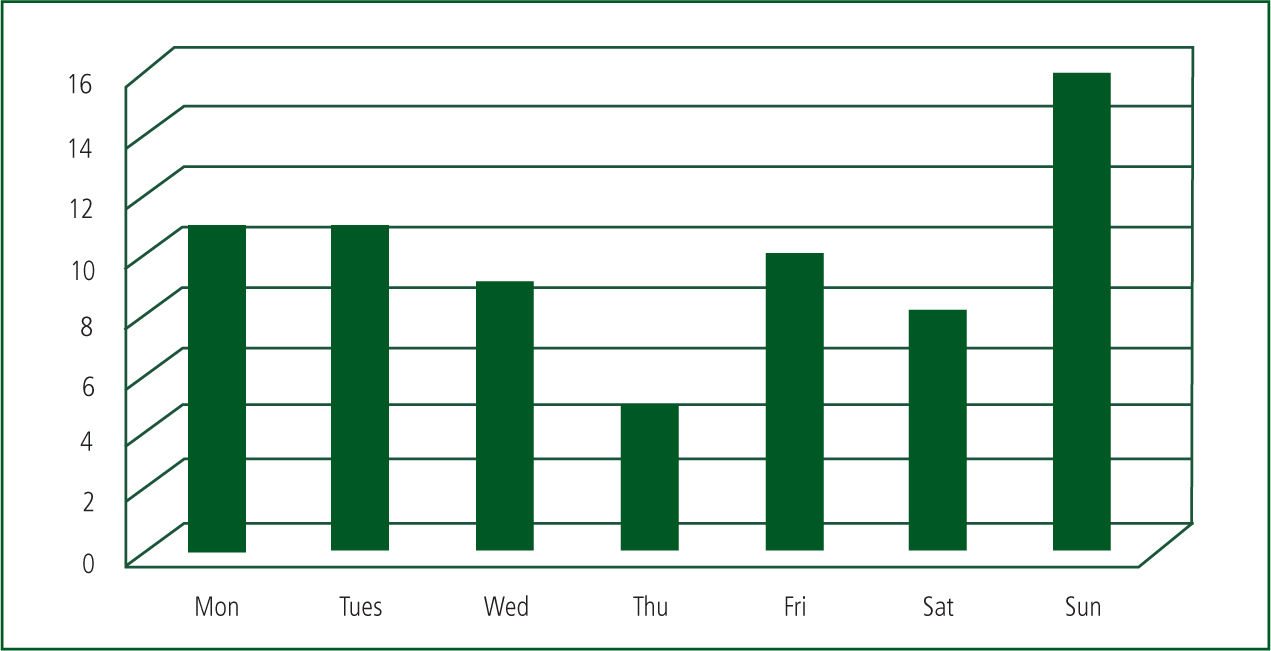

Almost a quarter of administrations took place on a Sunday and the peak time for administrations was between 18:00 and 22:00 (See Figures 1 and 2).

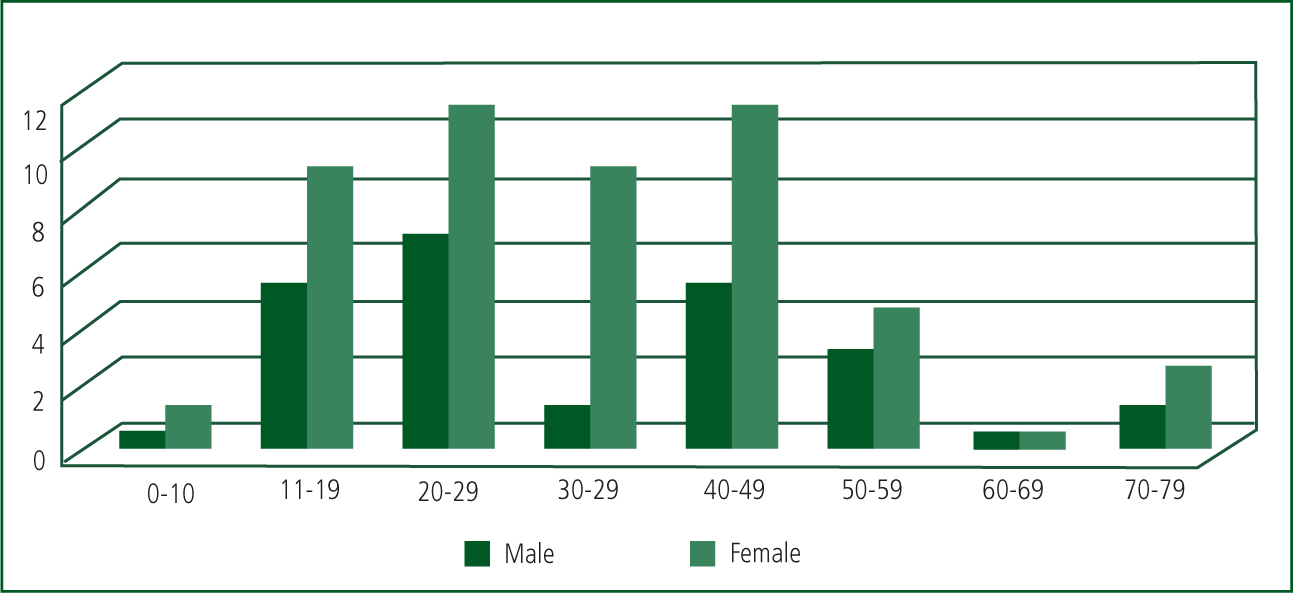

Female patients (age range 5–72 years) made up 68% of the trial sample, with males (age range 16–71 years) making up the remaining 32% (See Figure 3). The 5-year-old patient had taken an accidental overdose of paracetamol suspension and did not accept the charcoal.

The three largest paracetamol overdoses (90 g, 50 g and 35 g) were taken by males, the largest quantity taken by a female was 27 g. Although none of these four patients had taken alcohol, one third of patients in the sample had co-ingested alcohol.

3% of overdoses (n=2) were accidental, and of patients in the sample, 71% had a previous medical history which included a mental health condition.

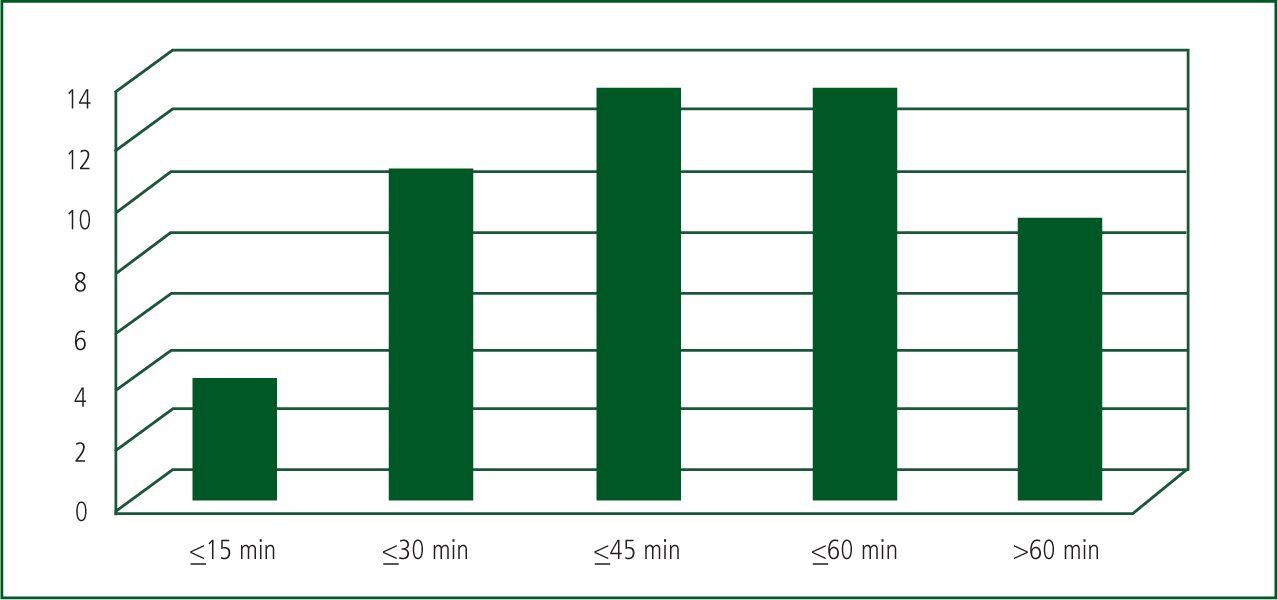

81.5% of patients received SDAC within the 1 hour time frame, which included the two largest paracetamol overdoses at 18 minutes and 42 minutes respectively (See Figure 4).

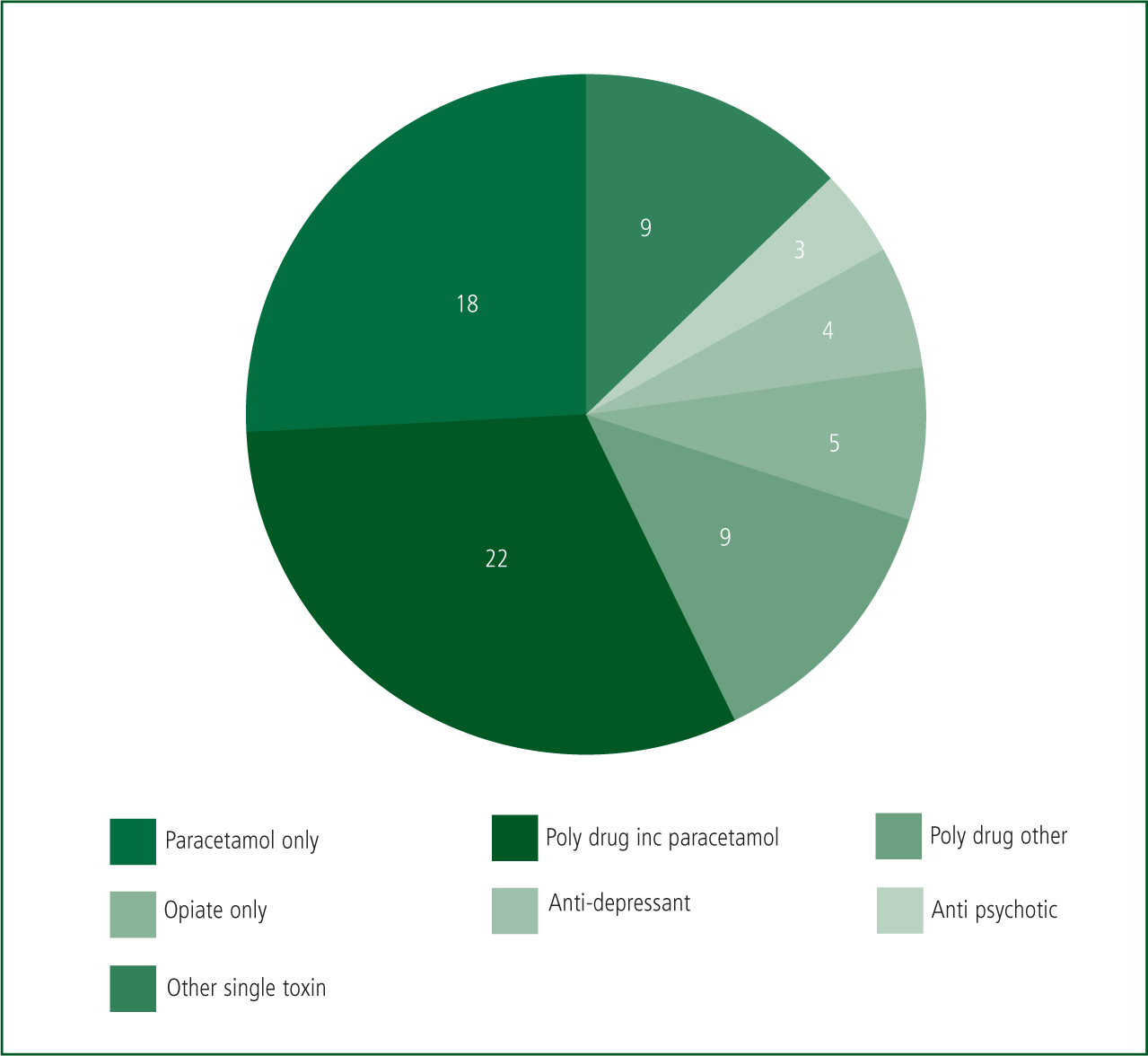

Crews encountered a range of ingested toxins which included tricyclic antidepressants, aspirin and paracetamol either alone or with other substances in 57% of cases (See Figure 5).

Toxbase was consulted for advice on 13 occasions, resulting in 13 administrations of SDAC on their recommendation.

Using National Poisons Information Service current advice (National Poisons Information Service, 2013) that paracetamol overdoses in excess of 75 mg per kg of bodyweight should be treated as hepatotoxic, and average bodweight figures for adult male and females (Office for National Statistics, 2001) (84 kg male, 69 kg female), it was deemed that any paracetamol overdose in excess of 6 g was considered hepatotoxic.

On this basis, 54% (n=38) of all overdoses were for hepatotoxic paracetamol overdoses. Toxbase advised on three further occasions that SDAC should be given: for a toxic dose of zopiclone and for lethal doses of aspirin and antipsychotic medication.

95% of all paracetamol overdoses were at or above the hepatotoxic level (n=38). Of these, 74% received SDAC within the hour.

Time on scene where SDAC was given was on average 20 minutes and 24 seconds. When SDAC was not given the average was 23 minutes and 35 seconds.

Clinicians reported vomiting on six occasions but quantities were small in their opinion.

The online staff survey was completed by 21 clinicians. 70% stated that they had not encountered any problems administering the medication. Of the six staff who had encountered problems, two incidents involved administrations to children and two involved vomiting, although amounts were small in their view and no ambulance cleaning was needed. 95% of clinicians encountered no difficulties managing patients after SDAC administration. One comment from an advanced technician suggested extension of the treatment to that grade.

Six staff rated Toxbase as giving helpful and clear advice, and 95% reported that they had found the PGD easy to follow.

Two clinicians reported charcoal solidifying in the bottle during cold weather. This had been easily remedied by shaking the bottle for the full minute recommended by the manufacturer.

Although unable to obtain any formal feedback from EDs, the linked clinicians at each department reported no problems and felt that the pre-hospital administration of SDAC had made an important contribution to their subsequent management of patients. No negative feedback was received through formal professional feedback routes and no adverse incidents were reported.

Conclusions

Most patients of self-poisoning attended by paramedic crews willingly accepted SDAC when offered. The medication was tolerated well by patients, with only six incidents of vomiting post administration. Two of these incidents occurred inside a SWASFT vehicle but neither required extensive cleaning.

Administration of SDAC did not adversely affect on-scene times for crews. The average time spent on scene was 3 minutes shorter where SDAC was given compared with when it was not. This may be explained in part by the fact that all patients given the medication would have had a GCS of 15, whereas those who were not included may have had a reduced GCS, with the possibility of associated management issues.

The NICE recommendation that SDAC should be offered by ambulance crews within 1 hour of self-poisoning was met on 77% of the 69 occasions on which it was offered.

While the average cost of a liver transplant (Longworth et al, 2003) is in the region of £;77 000, it would be difficult to say whether or not any individual administration of SDAC during the trial directly prevented this extreme intervention becoming necessary. However, where paracetamol is concerned, one large overdose such as encountered on four occasions during the trial, or a series of smaller overdoses, has the potential for leading to liver failure of this seriousness.

Two frequent questions emerged during the trial. Some clinicians believed that SDAC was for paracetamol overdose only. Clarification was needed that although paracetamol accounted for 54% of the toxins ingested, the treatment is suitable for a wide range of medications in overdose. Some confusion arose over the involvement of alcohol. It was necessary to clarify that, although charcoal will not adsorb alcohol, the concommitant ingestion of alcohol does not prevent SDAC administration for the medication part of the overdose provided the alcohol will not reduce the patient's GCS to below 15.

As a result of the research, SWASFT has adopted SDAC administration by paramedic crews as a standard treatment for overdose and the medication has been rolled out Trust-wide. A revised medicines protocol is being followed by paramedics in South West England and the Trust expects to administer approximately 1 425 doses of SDAC in the first year of its use, at a cost of £;14 000.

Limitations of the study

This was a small scale feasibility study in two geographical areas of one ambulance service. Nevertheless, the Trust's Medicines Management Group were satisfied with the findings of both the literature review and the feasibility trial, and activated charcoal has been adopted as a treatment for self–poisoning throughout the South Western Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust.

Key Points

Conflict of interest: none declared.