The paramedic role requires pre-hospital clinicians to make countless sound, logical and sensible decisions. In any healthcare setting, these decisions are related to the welfare, treatment and safety of a person, and this should not be forgotten. Sometimes paramedics may be faced with decisions that they feel less confident about making. However, concluding that not having the necessary skills, knowledge, or information to do so is not being indecisive; rather, it is sensible and safe, and shows good clinical judgement. Judgement is a term that is almost synonymous with the process of decision making, and is associated with carefully considering a situation before arriving at a course of action. It is something that is required in the vast majority of clinical scenarios.

Rational decision making

Decision making is a cognitive process, and no matter which model is adopted, the judgement is almost always based on sound reasoning: that is, it is rational. One approach to decision making is rule based or algorithmic. Here, choices are made using a set of rules, policies or protocols. The decision maker must select the correct rule to apply based on the specifics of the case presented to them. The use of algorithms should reduce risk and inconsistency, and ensure relevant information is used when making a judgement (Thompson and Dowding, 2002). There can, however, be concern that the rules are not flexible enough, or that the wrong rule could be applied. The algorithm approach is safe as long as the patient is not atypical or misread by the clinician. It does not allow for any deviation from the prescribed course of action, and clinician thinking or exploration is limited. Hadorn et al (1992) even relate algorithmic use to rigidity and the production of robots who do not think for themselves. To be clinically valid, algorithms need to be rooted in actual data and have an ability to deal with inherent uncertainties (Kassirer and Kopelman, 1990). Risk is addressed using strategies such as clinical assessment tools or decision trees, which encourage logical processing of available data.

Advantages of rational decision-making tools are that they are evidence based, and they prompt the decision maker to consider all relevant factors. These tools are good for inexperienced clinicians as they lead and guide the process. However, some disadvantages are that they are potentially more time-consuming than other forms of decision making, requiring rote learning on the part of the clinician, so may be linked to reduced flexibility of approach. In addition, they can be based on statistical probabilities, so can have an inherent risk and are not necessarily financially efficient, as well as possibly not fit for purpose in all patient groups (e.g. some patients with mental health conditions may not exhibit ‘standard’ behaviours or symptoms).

Phenomenological decision making

Phenomenological decision making refers to choices based on personal experiences. There are two main types:

Intuition theory

The majority of everyday decisions are made intuitively. The brain uses its experience to match decisions that it has made, observed or contributed to before with information from the situation that it is now required to consider. This may not be a reliable method of decision making, especially if you have been unable to gather sufficient information to form a prediction of cause, effect, and likely outcome. The less experienced the clinician, the fewer resources they have to match, and they then might take a ‘best guess’ at the decision without basing it on solid fact. Intuition is dependent on the decision maker correctly diagnosing the situation and storing the decision previously made in order to be able to recall it on later, similar occasions.

Intuitive judgements are made without using analytical methods and are therefore informal and unstructured (Farrington, 1993). Paramedics tend to use intuition as the primary diagnostic tool, but must realise that this is not the only method at their disposal, and that intuition is only the starting point in good clinical diagnosis (Brunton, 2005).

Intuition is, however, often the preferred method when it comes to caring for patients, providing a service related to the care industry and any other where there is a ‘team’ approach to working. This process creates a subconscious ‘pattern’, which can be applied in a near identical way on a future occasion or updated in the light of new evidence—in the case of the latter event, changing the initial decision should not be seen as indecision, but as flexibility of approach, and good use of the information available to you. This subconscious process forms in the conscious mind once the patient presents. The mind identifies similarities, recalls previous encounters and then creates a feeling of intuition that you instinctively act on. However, the key disadvantages are that it can be difficult to justify to others or to persuade them of a course of action, and is of little or no use for inexperienced clinicians. It cannot be easily taught, as intuition and recognition are experiential and vocationally-driven, not class-room acquired. It can lead to misdiagnosis if the analysis of clinical evidence is displaced by instant judgements based on previous experience.

Pattern recognition

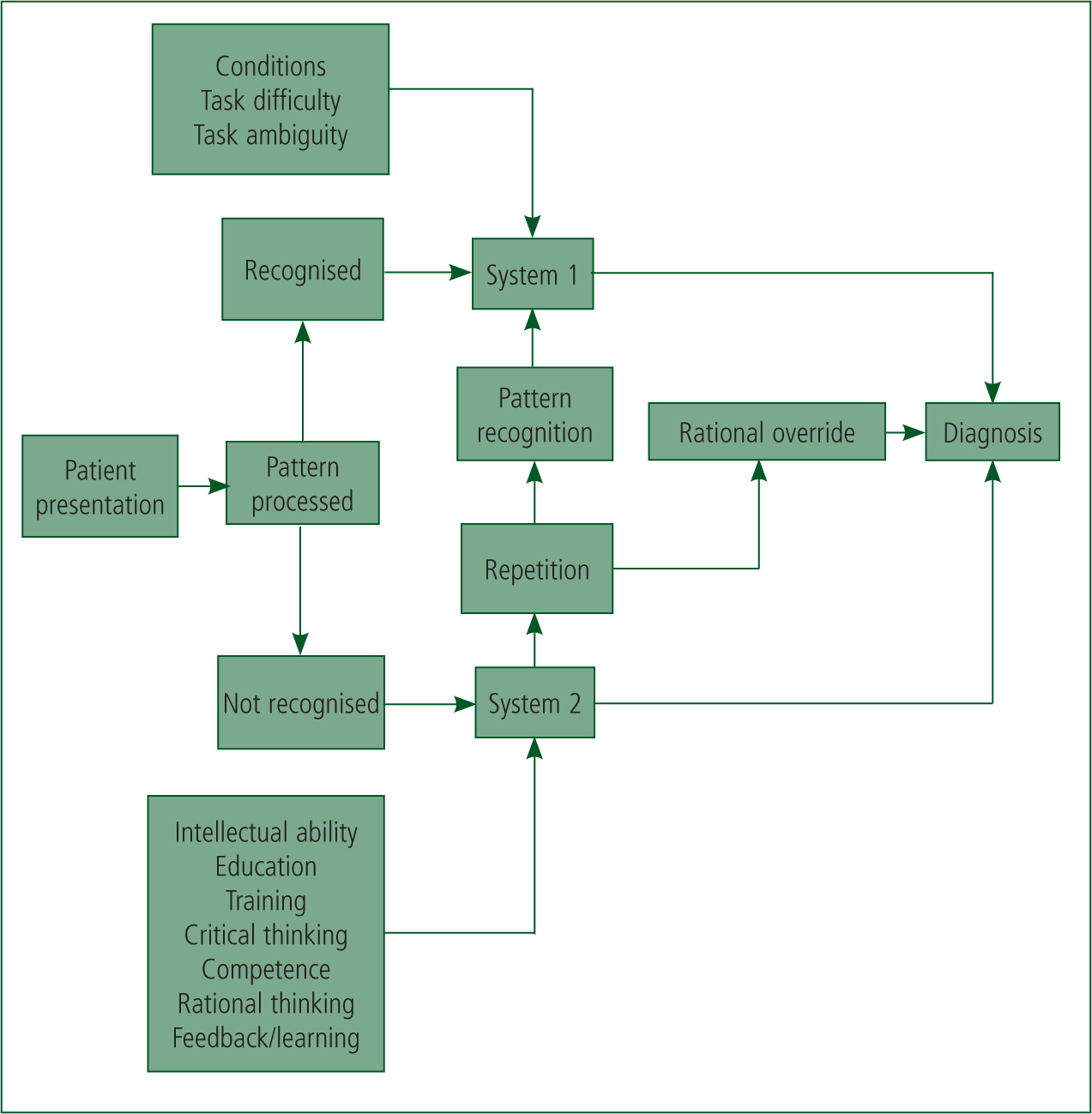

Pattern recognition is a skill-based activity. Unlike intuition, which can support near-instant decision making, it is done when time permits and there is no need to rush. A common occasion when it takes place is during the diagnostic phase of a consultation. A clinician faced with a new consultation will either quickly recognise the symptoms and signs using pattern recognition and be able to make a diagnosis, or not. Pattern recognition is an example of phenomenological decision making, and can be visualised using the sort of two-system model shown in Figure 1.

If the pattern is recognised, and correlates with external factors such as contextual, environmental conditions, System 1 operates and a diagnosis is quickly made. If no pattern is recognised then System 2 processing is required, whereby repeated cycles of data collection, analysis and interpretation take place (in the context of influences like training and critical thinking) until a conclusion is reached. Indeed, this approach can generate a number of possible diagnoses, which are progressively ruled out until only one logically remains. If a diagnosis presents itself during System 2 processing, the decision-making process moves to System 1. This overall concept creates the model of healthcare decision making termed ‘Dual Process Theory’ (National Prescribing Centre, 2011). Due to the uncertainty presented by some patients, the clinician will use shortcuts to try to link potential condition diagnosis with the information presented. This experience-based process is known as heuristics (Kahneman et al, 1982), and such decisions may be made quickly by relying on instinctive first impressions (Ambady and Rosenthal, 1992). It is not without its potential drawbacks, though. The process of creating patterns of associated situations and decisions allows the practitioner to form early impressions based on a variety of influencing factors, including characteristics of the patient's illness, immediate issues in the environment and resource availability (Croskerry, 2009a).

In summary, the main advantages of using pattern recognition in decision making is that it is quick, relative to other methods, tends to improve with experience, and uses subtle and obvious clues for information gathering. It is up to the clinician to use this form of decision making safely and responsibly, recognising that it may not be the most appropriate method for all situations.

Deduction and induction

Deductive reasoning is a process of decision making that draws conclusions based on facts and logic, sometimes called ‘working from the top down’. This type of reasoning moves from broad, general statements or ideas to specific conclusions that are based entirely on those facts. For example, deductive logic suggests that if a clinician observes a patient with malaria, then they can conclude with absolute certainty that the patient has, has had, or will develop fever during the course of their illness (Kyriacou, 2008). As long as the original ideas are valid, then the decisions and conclusions made by deductive reasoning will be valid as well.

Inductive reasoning draws on generalised information and makes very specific conclusions from broad statements. These conclusions and decisions are judged not for their validity, but rather on their strength and quality of evidence. Inductive reasoning is sometimes termed ‘working from the bottom up’, and while sometimes the conclusions it presents (and thus the decisions a clinician makes based on those conclusions) are right, there will also be occasions when they are wrong. The validity of type of decision making is much more at risk of subjective variables such as personal bias, where expectations, preconceptions and desires play a significant influencing role. Using inductive logic, if a clinician observes a patient with fever, the clinician cannot conclude with certainty that the patient has malaria because there are many other diseases that cause fever. Even if the clinician worked in Africa and had previously identified several consecutive cases of malaria in patients with fever, they could not be certain that the next patient with fever would have malaria (Kyriacou, 2008).

Hypothetico-deductive decision making

The hypothetico-deductive model of clinical decision making consists of several stages:

Seidel et al (2003) add a further stage to this of analysing and interpreting the patient's data to generate a range of differential diagnoses before the clinician tests and rules them in or out.

Under this model, the clinician sorts the clues and findings into logical groups using previous knowledge of symptoms and anatomical locations and landmarks (Dains et al, 2003). A hypothesis is formulated based on experience and knowledge of pathological, physiological and psychological conditions. It is likely that the hypothesis was first formulated at the initial contact, based on age, gender, race, appearance and presenting problem. Further interpretation of all the available evidence leads to refinement and a working diagnosis (Dains et al, 2003).

The clinician then looks at all patterns, clues and data, coupled with the physiological representation, predisposing factors and complications for this disease or injury in order to test the suspected condition and hypothesis. Considerations are then made as to whether this hypothesis encompasses all the patient's normal and abnormal findings, and whether it is the simplest explanation for these (Dains et al, 2003).

The clinical diagnostic process may be seen as an inverted funnel, where initial considerations are broad but as the history progresses, a smaller number of possible diagnoses remain (Tierney and Henderson, 2005). The slow, analytical and resource-intensive nature of the hypothetico-deductive approach is more likely to achieve the correct diagnosis than an intuitive approach (Croskerry, 2009a). It is a systematic model, which means it is far safer and allows for the removal of uncertainty, leading to effective decisions (Ullman, 2006). For every symptom there is a differential diagnosis, which can include rare diseases or conditions with atypical presentations. Experienced clinicians will use epidemiological factors such as the patient's age and gender while integrating information. The prevalence of the suspected condition(s) along with the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic tests and historical information, are also aids in hypothesis testing (Tierney and Henderson, 2005).

When we use intuition, we decide on the most likely diagnosis then carry out tests to prove ourselves right. Generally, we all hate to be proved wrong, so there is risk that we will subconsciously fit the results to our diagnosis, disregarding evidence that does not fit. By ruling out conditions systematically we can avoid this trap because by testing and ruling out diagnoses based on results, only the most probable diagnosis will remain.

Hypothetico-deductive clinical decision making is used only rarely by paramedics due to the inherent uncertainty arising from emergency situations, which present relatively little information in a short timeframe (Jensen et al, 2010). Decision making by paramedics during emergency calls can be improved with increased understanding of a diagnostic process. For example, paramedics need to become more aware of the accuracy and limitations of algorithms, and engage with a variety of clinical diagnosis tools, as described by Croskerry (2003).

Conclusions

Kovacs and Croskerry (1999) point out that clinicians use a variety and range of clinical decision-making approaches. These are dependent largely on the unique characteristics of individual clinical situations and the environments in which paramedics find themselves.

The role of the clinician is a complex one. It centres on performing a range of assessments aimed at gathering, evaluating and synthesising information that relates to a patient's presentation, before deciding on appropriate treatment and transport decisions (Sanders, 2005; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2008). Throughout this decision-making process, clinicians must continuously evaluate and judge the degree to which they are making the correct clinical decisions in relation to a particular patient (Parsons and O'Brien, 2011).

Generally, clinicians need to improve their awareness of clinical decision making: using intuition might well have a role to play coupled with heuristics and bias, but it has its limitations and risks. However, hypothetico-deductive reasoning has a prominent place (Jensen et al, 2010) and should be embedded into education and everyday use.