Lifestyle, modern living and suffering through health and disease have come to influence our ife expectancy, understanding human processes and pathophysiology are fundamental to improving life experiences and ensuring continuing health. Respiratory conditions in particular are at the centre of healthcare currently as a result of COVID-19.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a debilitating disease of the lower airways of the respiratory system and is a leading cause of death (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2020). Most experiencing a breathing problem will invariably use verbal communication to describe their experiences. COPD affects all aspects of day-to-day life and an exacerbation inevitably involves breathlessness. In 1908, Hill and Flack stated the following:

‘There is no more frightening and unpleasant feeling than that of feeling breathlessness and the sense of impending death’.

Over a century later, this statement still stands. So what exactly is ‘breathlessness’ and can service users in prehospital care accurately convey the meaning of such? Do health professionals realise the implications of the verbal descriptors used, and can such words be used to facilitate best practice?

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this module, the paramedic will be able to:

Background

Breathlessness is a term used along with a variety of other descriptions such as dyspnoea, shortness of breath, chest tightness, difficulty catching breath and what most would interpret as simply not breathing in sufficient oxygen. Therefore, the most obvious reaction is to provide supplementary oxygen to resolve the issue. As Campbell and Howell (1963) reported, the afferent/efferent mismatch gives rise to shortness of breath and therefore deviation of this causes or intensifies the sensation. The afferent/efferent mismatch is the difference between the need for oxygen as received by the receptors and the ventilation and intake of oxygen by the lungs. This two-dimensional model can be used to illustrate a perceived mismatch between the ventilation demand and perfusion giving a progressive feeling of inadequate breath.

‘This does not consider emotional and behavioural changes which are known to influence not only the cardiac, but also respiratory systems’.

An often-cited definition of dyspnoea was first advocated by Comroe (1966) as that ‘which includes not only the subjective perception of laboured breathing but also the patient's reaction to the sensation’. This three-dimensional model then suggests that dyspnoea is a complex indicator with various mechanisms and feedback systems, in addition to behavioural and emotional situations, resulting in persistent symptoms. So does the impact of the stimulus to breath and resulting breathlessness give rise to verbal descriptors which could differentiate and aid the understanding of symptoms? Comprehending the meaning of these descriptors used aids the understanding of how language and disease are linked.

Descriptors in cardiac assessments are used to assist the evaluation of the pain experienced, (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2010). During a heart attack, generally the first sensation to be felt is pain (Association for Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2006). The unpleasant sensation causes the adaptive mechanism of the patient regaining homeostasis but the pain leads to them to seek further treatment or investigation. Verbal descriptors used during such an episode include heavy, squeezing and crushing.

This pain can be felt in many different dimensions throughout the body. As pain has several dimensions, breathlessness can be shown to arise for many different reasons as well (Harver et al, 2000). Words such as ‘rapid’ suggest increased ventilation and raise oxygen intake in addition to reducing carbon dioxide within cells. Using these descriptors as a basis to interpret the cause of breathlessness can lead to an improved perception of the sensations felt and thus aid therapy.

Verbal descriptors are spoken language, and so this language forms part of patients' communication of the ‘problem’ they are trying to describe. Language is ‘a system of sounds and words to communicate’ (Turnbull, 2010) and communication is the sharing of ideas or conveying a sense of emotion that can give anxiety relief.

The interpretation of breathlessness directs prehospital therapeutic treatment towards a resolution of the ‘problem’. Therefore, understanding the language of breathlessness enables enhanced awareness of the principal cause for the ‘problem’ experienced (Yorke et al, 2009). In the same way, descriptors of shortness of breath could be used to evaluate an exacerbation in COPD. Patients with COPD generally find breathing challenging on a day-to-day basis, hence talking becomes a struggle and can lead to depression in the long run (Maurer et al, 2008). It is in times of stress and helplessness that these exacerbations tend to occur. Understanding the cause of the breathlessness can enhance patient care (Leupoldt et al, 2007) as the ‘prevention, early detection, and prompt treatment of exacerbations may impact clinical progression’ (Wilkinson et al, 2004).

The current Joint Royal College Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) guidelines for dyspnoea make use of the visual analogue scale (VAS) to assess the severity of breathlessness experienced (AACE, 2006). This scale is not easily understood, and can be misinterpreted if people misunderstand what is being measured. According to the American Thoracic Society (ATS) (1998), ‘problems encountered in administering the VAS are difficulty seeing the line and anchors as well as forgetting how the scale is oriented.’ Subsequently, the present guidelines use a two-dimensional tool in order to quantify a three-dimensional problem.

This review seeks to consider research in this field in order to evaluate the effectiveness of these words as an assessment tool for COPD.

Method

This review of literature takes account of research gathered in the field of respiratory medicine, specifically targeted at the individual with COPD and the communication used when breathless.

The evidence gathered from this review will result in more informed practice for the service user and the health professional in the prehospital field. The key words and searches used in this literature review appear in Box 1.

| Key words | Searches |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Evidence-based medicine involves answering a question. In order to formulate an analysis into the use of verbal descriptors, the PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome) method was used to facilitate a well structured question.

The PICO method was used to grade and filter the available literature. Six studies relevant to this topic, which used the keywords within the search, were included. Furthermore, in order to keep within time restraints, only publications between 2002 and 2012 were included in the review (as this review was originally published in 2012). Despite the search criteria, including any assumed variations on the term ‘pre-hospital’, only studies pertaining to the in-hospital setting were obtained. Limitations were used to select papers relevant to only breathlessness/dyspnoea and COPD, and papers including heart failure and asthma were excluded.

The information sourced was selected using research carried out by specialist respiratory knowledge bases (i.e. GOLD and CHEST) and a majority of the studies were conducted in England or Germany, with verbal descriptors from the research translated. One study was Australian but all were carried out in English.

Discussion of findings

The size of studies varied between 10–358 participants, consisting of healthy individuals and those diagnosed with COPD. This then gave a broad range from 18–65 years of mixed male and female groups.

Although the larger studies were carried out on volunteers experiencing respiratory problems, results carried out on ‘healthy’ individuals gave a retrospective view of data produced. The collective data in these studies were reviewed using hierarchal techniques rather than separating sufferers and non-sufferers. This method is one used in statistics, which divides the descriptors into clusters of similar words. On reviewing the literature published, this yielded several common themes, including:

This review will demonstrate the significance of words in relation to these themes used by service users to the health professional in the prehospital arena when assessing and managing the issues behind the breathlessness sensations experienced.

All studies gathered statistics, using hierarchal and RASH (Self-adaptive Random Search Method) techniques (Yorke et al, 2009), from healthy and respiratory participants (i.e. varying conditions, not just COPD subjects) using either synthesised words or reproduced descriptors from preceding breathless analysis.

Leupoldt and Dahme (2005) used the VAS, as referred to in the JRCALC dyspnoea guideline, and asked participants to score intensity and unpleasantness. The information drawn from all papers suggests there are clusters of between five to twelve words which were common to all research.

Verbal descriptors

The words used to describe the sensations of feeling breathless have been termed, ‘associated descriptors’. Harver et al (2000) interpreted ten associated descriptors which replicated three definite dimensions independent of the pathophysiology or disease condition. Leupoldt and Dahme (2005) demonstrated that the perceived ‘unpleasantness’ increased more than the level of perceived intensity of breathlessness using the VAS rather than descriptors. This supports the understanding that descriptors being used in the first instance are those for the ‘unpleasantness’ of breathlessness/affective pathway and that these can be differentiated from sensory or intensity inputs.

Leupoldt et al (2006) conferred that verbal descriptors obtained were related to clusters which formulated four sub-dimensions derived from two higher dimensions namely ‘work’ and ‘air hunger’.

Leupoldt et al (2007) (Table 1) proposed that the verbal descriptors used revealed ‘a distinct pattern depending on the intensity level and not influenced by age, gender or lung function’. The descriptors which had been provided in this study were translated, so had a cross-language relationship.

| Unpleasantness | Cluster | Verbal descriptor given |

|---|---|---|

| Physical (Affective) | Effort | Breathing is heavy |

| Speed | Breathing is rapid |

|

| Intensity Sensory Effective | Obstruction | Gasping for breath |

| Suffocation | Cannot get enough air |

Although these data were consistent with others, potential translation analysis would leave this research open to criticism. Yorke et al (2009) noted that the distress or difficulty encountered suggests different words for different diseases and also words for the physical and affective components of dyspnoea. An identical conclusion was presented by Williams et al (2008) although the non-COPD descriptors were specifically targeting physical descriptions of breathlessness.

Dimensions of ‘breathlessness

In order to understand the different perspectives of breathlessness, differing paradigms can be applied. Harver et al (2000) support three dimensions to dyspnoea: ventilation, perceived intensity and difficulty in the mechanics of breathing. Leupoldt and Dahme (2005) showed that differentiation could be made between affective and dyspnoea intensity, i.e. two dimensions using a very small study sample. The perceived unpleasantness (sensory impression) of dyspnoea escalated more rapidly than the intensity (potency). The depth of breathing or ‘ventilatory appropriateness’ gave words describing the mechanics of breathing, moreover, relating to the inspiratory volume, i.e. breathing more. This infers that both sensory and affective elements of breathlessness can be separated, thus providing an opportunity for the development of further assessment tools (Leupoldt and Dahme, 2005).

Leupoldt et al (2006) offered four dimensional clusters for dyspnoea: namely, effort (work); speed; obstruction; and suffocation (air hunger). Again, the correlations of the study, though small, produced four dimensions to breathlessness using verbal descriptors provided by the participants. In a later study, Leupoldt et al (2007) presented a further cluster to previous studies in that shallow breathing also gave noticeable descriptors in varying levels of dyspnoea expressed by COPD participants. A further programme using COPD volunteers and age-matched adults carried out by Williams et al (2008) advocated that descriptors have the potential to distinguish older individuals with and without COPD, and that shortness of breath is not a true characteristic of ‘old age’ or ‘unfitness’. These descriptors used by an older person could be employed to instigate a further medical assessment.

Although some were predetermined descriptors, some were the volunteers' own words and some scored using the VAS. The final study drew all of these methods together and demonstrated that using quantative scales already in use (e.g. Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale, BORG intensity and distress scale, hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), such instruments can standardise the dyspnoea experience to facilitate the understanding of the cause.

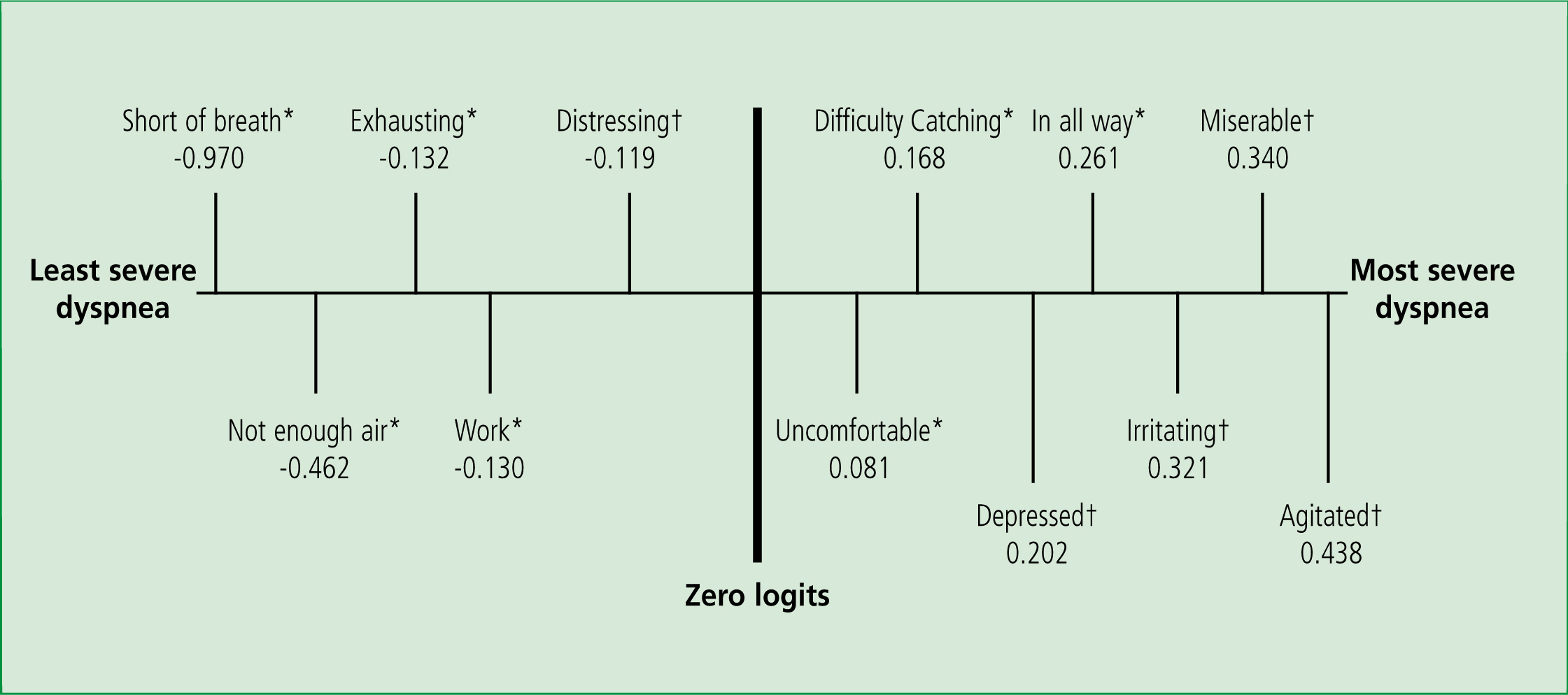

Use of the ‘Dyspnoea–12’ (Table 1) supported the use of descriptors as a method of quantifying breathlessness. A verbal descriptor scale could provide the quality of the breathlessness experienced progressively rather than conveying time-specific determinants.

Dyspnoea has an analogy to pain, as it is an unpleasant and frightening experience which induces the sufferer to seek its origin. Banzett and Moosavi (2001) state:

‘One of the most important contributions to the development of standardised instruments that can convey meaningful information about pain sensations has been the recognition of the multidimensionality of pain.’

Verbal descriptors support the recognition of the various dimensions resulting in dyspnoea.

Conclusion

The many different concepts of breathlessness within the evidence suggest there are four interacting attributes which collaborate to the final sensation within the body. From these studies, a compilation of descriptor words which when used, could incorporate the dimensions advocated (Table 2). JRCALC practice guidelines for breathlessness refer to the dyspnoea guideline; this determines the degree of dyspnoea using the VAS, which is poorly understood. However, the information suggests that employing service users' own verbal descriptors, which are easy understood by both user and caregiver, may provide a more meaningful comprehension of the dyspnoea experienced.

| Dimension | Verbal descriptor |

|---|---|

| Physical Work Mechanics | My breathing requires work |

| Affective Intensity | My chest feels tight |

| Ventilation | I feel I am suffocating |

It is acknowledged that the capacity of the respiratory muscles is reduced in COPD and inspiration and expiration are affected even in normal breathing. Furthermore, ‘the neural respiratory drive is increased’ and a key quantity of ventilation feedback is expected to keep homeostatic control (Jolley and Moxham, 2009). This ventilation–perfusion mismatch causes adaptive behaviour and a corrective pathway is prompted to regain homeostasis within the body systems. These adaptive mechanisms elevate the situation to seek further treatment or investigation.

It is apparent from these studies that there are around twelve words recurring during periods of breathlessness. These expressions were directed towards four different dimensions of breathlessness. Certain phrases were directed to purely physical descriptors and the path of the sensation led to very definite words. Studies also gave clusters of descriptors which suggested different diseases directed participants to certain descriptions (Williams et al, 2008).

These findings are comparable with pain descriptors (i.e. crushing chest pain in myocardial infarction) and, although the descriptors in isolation cannot separate the reasons for the breathlessness, it can highlight a more holistic view of a very misunderstood sensation. The same results were seen using words that had been translated, although all studies were carried out in the English language, inferring that there could be some further study for cross-cultural use of language.

At present, the VAS is sufficient for general levels of dyspnoea. However, to gain a better understanding of the breathlessness encountered, a more detailed scale is required to enhance care and deliver a clearer management plan. The best person to describe how breathlessness is affecting them is the individual themselves and it is this that can be used to best effect. If this language is ignored, then just like pain, it can intensify or obscure the true suffering of the individual.

In GOLD conferences and reviews, respiratory exacerbation has being likened to myocardial infarction (i.e. the attack being a precursor to something bigger). Therefore, if enhanced evaluation of these attacks was achieved using further technique such as the use of verbal descriptors of breathlessness, as in pain, this process can only prove to enhance the management of the patient and highlight the need for further review.

The emotional response and affective descriptors to breathlessness have a significant relationship to severity of COPD, as the words volunteered demonstrate. Affective descriptors may reflect the degree of threat imposed by the sensation and predict the likelihood of long-term behavioural changes. In order to manage breathing in an episode of breathlessness, understanding the cause of the problem variable will facilitate the response.

Recommendation

In order to act as autonomous practitioners at the forefront of definitive care, paramedics are bound to their standards of proficiency to provide the best and most up-to-date practice to their service users (Health and Care Professions Council, 2014).

It is this ‘language of problems’ that instigates care-seeking and provides verbal descriptors which highlight the aspects requiring support. The precipitant factors are complex and a deeper understanding using descriptors provided could aid both care provision and care planning. A large number of assessment tools used for the evaluation of breathlessness rely on the individual reporting what they cannot do rather than what they can. A tool such as the Dyspnoea-12 (Figure 1) or one such as asking to describe the breathlessness could have an impact on the outcome. It is suggested that in the interpretation of language in prehospital care where patients require effective methods of assessment in a timely manner, the simple use of verbal descriptors can enhance therapeutic care.