An apprenticeship comprises a job with training to industry standards and is a protected title (Department for Education (DfE), 2022). Apprenticeships are key to ensuring that private and public employers can recruit and develop their workforces through the provision of technical knowledge and practical experience to secure a wide range of skills and behaviours (DfE, 2022). Multiple, interchangeable terms are used for apprenticeship offerings at universities. For this review, the term ‘degree apprenticeship’ (DA) will be used, and this study will appraise DAs exclusively through the paramedic lens.

Nawaz et al (2022) identified that DAs allow learners to study towards a degree while participating in real-world, on-the-job training through the combination of vocational work-integrated learning and part-time study.

DAs are created in collaboration with businesses, universities and, where appropriate, professional bodies with the goal of fostering the development of advanced skills necessary for the future. The Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) (2019) has created a statement of characteristics outlining the standards for DAs. The learners on a DA typically work for a minimum of 30 hours per week, and academic learning is integrated with off-the-job study to fit around full-time employment. The study curriculum runs academic learning and work-integrated learning side by side so apprentice learners earn while they learn.

Upon completion of an apprenticeship, the learners on a BSc (Hons) in paramedic science programme will be eligible to register as a paramedic with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), and practise under the protected title of paramedic (QAA, 2019). The College of Paramedics (CoP) 2024 Curriculum Guidance Framework, the QAA (2019) benchmark statements for paramedic science and the standards of proficiency for registered paramedics (HCPC, 2023) have been mapped against these standards to build the award's structure. A paramedic's comprehensive knowledge and skill set arise from their learning, which has a significant practice-based education (PBE) component aligned to the requirements of the role (Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education, 2023). PBE assesses knowledge, skills and behaviours (KSBs) through a variety of modules and practice placement workbooks. PBE and time at university contribute to off-the-job hours within the apprenticeship.

Basit et al (2015) suggest that PBE forms a key element of the DA, with great significance placed upon the tripartite relationship formed between the apprentice, the university and the practice educator (PEd). The term ‘educator’ is used over the common term ‘mentor’ as the CoP (2020) suggests that the responsibility of this role is far greater than just mentorship. The assigned PEd ensures a constructive link between theory and practice, and is responsible for the teaching, assessing and facilitation of learning for the apprentice in practice.

However, evidence suggests (Basit et al, 2015; Rowe, 2018; Bass, 2022) that there are several difficulties and barriers for all stakeholders involved regarding the implementation, collaboration and application of PBE within the DA.

Aim

The concept of apprenticeships within the ambulance service is comparatively new and under-researched. The existing knowledge base is drawn from undergraduate paramedic degrees and other apprenticeships, and this informs PBE. This UK-based scoping review aims to identify barriers and challenges around PBE linked specifically to paramedic DAs.

Methodology

Munn et al (2018) state scoping reviews clarify key concepts and definitions and identify gaps in knowledge. Scoping reviews report on the types of research that address and inform practice, and their general purpose is to identify and map available evidence (Mak and Thomas, 2022). As DAs within paramedicine are under-researched, this methodology was deemed appropriate over others to ensure a broader evidence base was examined.

This review applied Arksey and O'Malley's (2005) five-stage methodological framework with the intention of examining the literature on current DAs and the barriers and challenges to PBE.

Stage 1. Identifying the research question and key words

Before identifying the research question, an exploratory review of the literature on DAs helped refine the scope of the present evidence. Because multiple terms are associated with DAs and PBE, this background search identified key words for the search strategy (Table 1).

| Apprentice* | Paramedic* |

| “practice educator” | “Higher Apprenticeship” |

| Educator* | “Degree Apprenticeship” |

| Mentor* |

Based on the initial exploratory review, through the use of a population, concept and context framework (Pollock et al, 2023), the following research question was identified: ‘What are the challenges and barriers for PBE within UK paramedic DAs?’

Stage 2. Identifying relevant studies

In keeping with the Arksey and O'Malley (2005) framework, the search strategy was developed in May 2023 to include publications within the time frame applicable to the research question (2013–2023), relevant to the setting of interest (UK), and population of interest (paramedic DAs).

Although a scoping review is designed to cover a broad spectrum of literature, these criteria were used to guide the search and help filter for relevant sources. It is acknowledged that, as paramedic-specific research in the area of DAs is limited and because of the embryonic nature of apprenticeship programmes in paramedicine, other professions and academic levels were considered.

This review included primary studies retrieved from the CINAHL, EBSCOhost, Medline, and PubMed electronic databases. Secondary searches were completed using Google Scholar and the Trip database. Reference lists of reviews found through the electronic search were checked to ensure that relevant articles, including grey literature, were included in the scoping review.

As suggested by Levac et al, (2010) the team used an iterative process to identify key search terms. Initially, the following key words were used: ‘higher apprenticeship’, ‘apprenticeship’, ‘practice-based education’ and ‘paramedic’. The articles included further terms, which were then added into the search (Table 1). Based on the initial background research, the eligibility criteria (Table 2), were agreed.

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Language | English | All other languages |

| Date | 2013–2023 | More than 10 years ago |

| Refers to keywords in title or abstract | Majority present | Less than majority presen |

| Availability | Full text | Less than full text |

| Setting | Degree apprenticeship: any UK only | Further education Non-UK |

| Type of publication | Quantitative and qualitative primary studies Legislation and policy | Literature reviews Editorials Opinion pieces |

| Context | Employer/practice-based learning focus Subject relevant to research question | Granular mentorship focu Subject not relevant to research question |

Stage 3. Study selection

The third stage of the Arksey and O'Malley (2005) framework concerns the process of selecting studies for the scoping review.

A team review approach was carried out, with the lead researcher assigning studies for review. A two-stage screening process was conducted to identify relevant studies. A member of the team screened the titles and abstracts of the articles. Those that did not meet the eligibility criteria identified in the second stage of the protocol (Table 2) were excluded. For those fulfilling the eligibility criteria, the full article was retrieved.

A sample of the retrieved articles was then screened by another team member to ensure the application of the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the review was consistent. Titles and abstracts of the articles for which the first reviewer could not determine eligibility for inclusion were also reviewed. Discrepancies involving article selection were discussed with the lead researcher until consensus was achieved to include or exclude the article in the full text analysis.

The lead researcher then completed a second screening, which involved examining the full document to ascertain relevance to the research question. A total of six studies were deemed to contain significant data relating to the research question. These were Saraswat (2016), Mulkeen et al (2017), Roberts et al (2019), Smith et al (2020), Fabian et al (2021) and Quew-Jones (2022).

There were no studies specific to the challenges and barriers faced within the paramedic DA, so analysis and evaluation are drawn from other professions, and the studies selected contained themes of significance for this area of research.

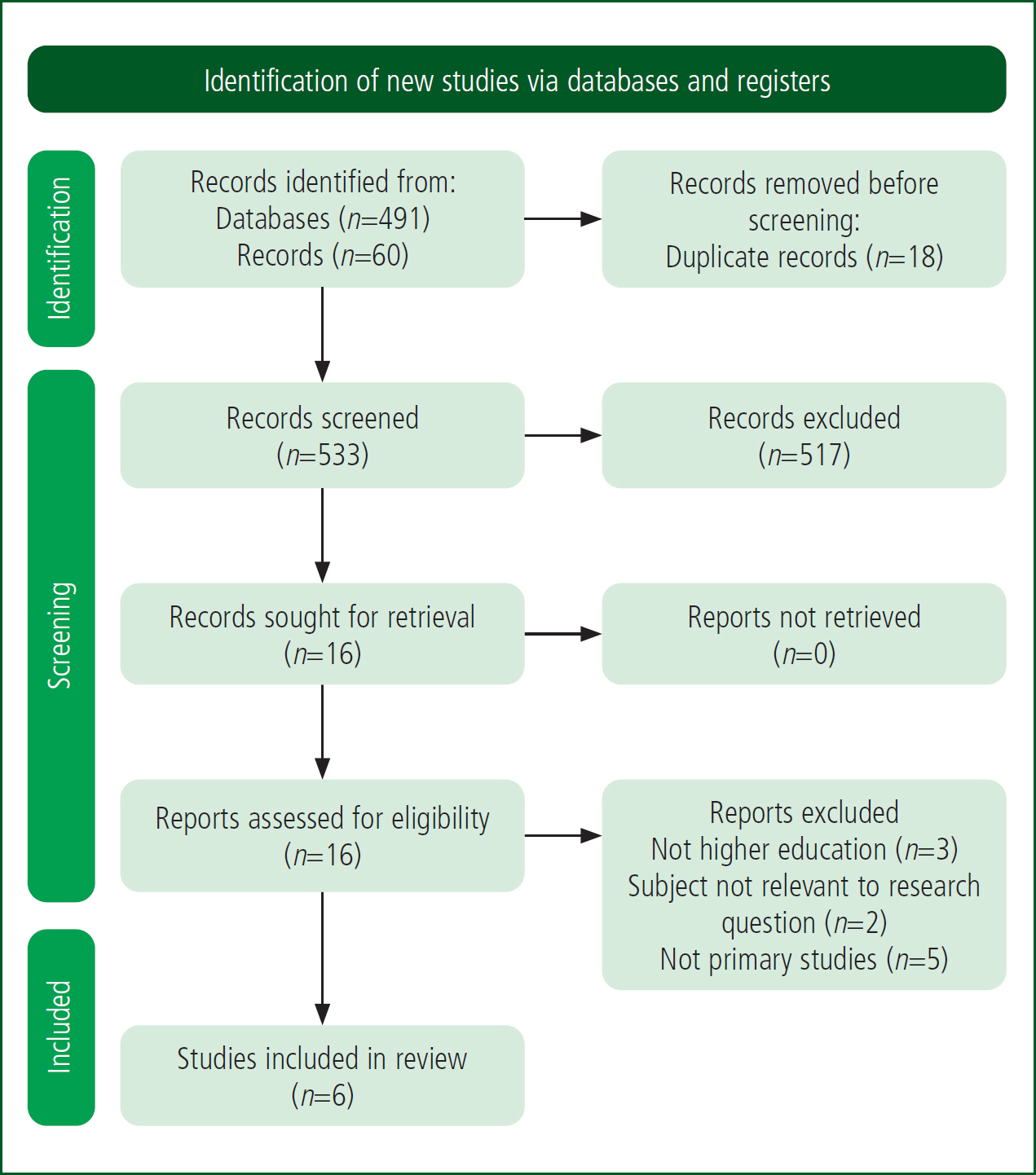

The search strategy and article selection process were reported using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flowchart (Figure 1) (Tricco et al, 2018).

Stage 4. Data charting and collation

The six selected studies were critically appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2024) qualitative review checklist. Although not formally required by the methodology of a scoping review, each article additionally underwent a full-text analysis, data extraction and data charting process by the lead author of this paper (Table 3).

| Author (date) | Methodology and data collection | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Saraswat (2016) | Prospective, semi-structured interviews | This study examined the provision of apprenticeships by English further education (FE) college and highlights some of the key drivers of delivery and possible challenges that can be faced b providers in any expansion of apprenticeships. Staff perceptions on the new apprenticeship standards are also presented. The data suggest several key issues regarding the development and barriers of apprenticeships within FE colleges: growth potential, government agendas, employer demand, integration and progression, cost-effectiveness, employer perception, college issues and evaluation/grading of assessment. The authors concluded that addressing these factors requires a strategic commitment to employer management, investment in recruitment and careful evaluation of costs and benefits. Assessments need to be refined to ensure effective measurement of achievement and recognition of competence. While this stud was based on FE apprenticeship programmes, the findings can be generalised to degree apprenticeships, with many findings applicable to paramedic-degree apprenticeships |

| Mulkeen et al (2017) | Prospective, semi-structured interviews | This study used semi-structured interviews to uncover stakeholders' perceptions, opinions and experiences of designing and delivering degree apprenticeships. The main topics included were programme design and delivery, mapping of accreditations and understanding the ownership of an apprenticeship. Main themes derived from data analysis were difficulties in engaging stakeholders, concerns from employers regarding adequate practice-based learning support and mentorship, development of competent mentors, challenges with teaching, learning and assessment strategies, and barriers surrounding complementing university-based and work-based learning. The study concluded that emphasis should be placed on the relationship forming between the university and other stakeholders and, while degree apprenticeship programmes will provide a new way to finance and deliver higher education, knowledge and skills, their success is dependent on collaboration, cooperation and co-creation between all stakeholders. One limitation of this study was that one stakeholder—the learner—was not included, so it lacked the student voice and perception within topics discussed. The study findings aligned with paramedic degree apprenticeships in terms of similar concerns surrounding mentorship, endpoint assessment challenges, assessment issues, barriers to co-creation and responsibility for learner progression |

| Roberts et al (2019) | Prospective, unstructured interviews | The aim of the study was to develop a deep understanding of the nature and impact of the workplace mentor role in degree apprenticeships and to investigate a theoretical model of degree apprenticeship workplace mentoring activity, with findings used to develop a set of principles to support the development of effective mentoring. Unstructured interviews were carried out, with the discussion guided by prepared prompts, to explore the experience of mentoring within a chartered manager degree apprenticeship programme. Three main themes arose: expectations of mentorship; mentoring impact; and barriers to effective mentorship practices. From this data, the authors developed a set of guiding principles for supporting effective mentoring practice in degree apprenticeships. The data gathered support the validity of the proposed model, with most mentoring activity focusing on actively facilitating learning and developing an appropriate professional identity. However, support for achieving the apprenticeship standard was constrained by mentors' lack of information, suggesting a need for mentor development. These principles can support the development of organisational and personal mentoring strategy and practice. However, this study used a small sample so a larger study is needed to establish whether any changes are required to the guiding principles and to research into the generalisability of these principles to other apprenticeships. Several key findings from this study are in line with paramedic degree apprenticeships as the key element of these is linking theory to practice. Other areas identified and aligned were mentor commitment, mentor knowledge surrounding the apprenticeship and learner progression, mentor education and support, stakeholder communication barriers and responsibilities for assessment and evaluation |

| Smith et al (2020) | Prospective, survey and interviews | This study aimed to analyse the expectations and experiences of apprentices following the introduction of a new model for apprenticeships in the UK, and to provide insights into the effectiveness of degree apprenticeships as a win-win model for both apprentices and employers. Two-pronged collection took place to gather the data for analysis. The themes identified included: apprenticeship policy aims being framed primarily as meeting the needs of employers to access skilled employees; the degree apprenticeship was presented as an opportunity for employer and apprentice to benefit from multi-stakeholder collaboration and skills development; and a win-win theme emerged from policy documents and materials designed to encourage participation from all stakeholders. The findings suggest that degree apprenticeships have potential to be a win-win model for both apprentices and employers, bu there are challenges to be addressed in terms of implementation and ensuring that all stakeholders benefit equally. This study was generalised to higher education apprenticeships, and the findings resonate with evaluation surrounding mentorship concerns, roles and responsibilities, end-point assessment challenges and difficulties around apprenticeship standards and requirements |

| Fabian et al (2021) | Prospective, survey based | The study aimed to identify apprentices' viewpoints of the degree apprenticeship by exploring aspects of belonging, support, challenges and views of the learning experience. Several themes arising from surveys included the value of communication, difficulties in achieving a work-life balance, lack of support, role identity, employer commitment issues and a sense of belonging within the workforce. The study concluded that having an understanding from the apprentice learner's perspective affects how apprenticeships progress, through adapting and aligning to stakeholders, such as employers and universities. While not paramedic-based, issues and barriers were similar so can be generalised. Limitations included a sample of only 35 participants, not all of whom answered each question, which leads to non-compliance bias in the results. Therefore, it is not possible to ascertain whether the viewpoints are generalisable to all apprentices on the course in this study. Likert scale questions with predetermined statement were used, which do not allow for student voice, expansion and clarification |

| Quew-Jones (2022) | Prospective, action research—focus group discussion/action learning (AL) sets | This study aimed to explore how collaboration between employers and FE/higher education (HE) colleges/universities providing apprenticeship courses can enhance the curriculum for workplace-based learning. The study used action learning sets/discussions to explore ways to enhance the apprenticeship curriculum through employer collaboration. The action learning sets were guided by a lead question and focused on how the apprenticeship ambassadors, who lead apprenticeships within their organisations, could influence curriculum content, design, delivery and evaluation. The emphasis was on employers and university providers working together to find potential solutions and models of best practice rather than academics teaching employers how to contribute. These discussions were integrated into an action research cycle, where emergent enquiries were combined with existing practical knowledge and applied to solve the shared problem of putting knowledge and skills gained during learning into practice. A common concern was that workplace-based learning lacked clarity, making it difficult for stakeholders to connect with the concept, and a lack of apprentice identity made it harder for apprentices to apply the knowledge they were gaining and contribute to the workplace. To address these, a definition of workplace-based learning was created and the author investigated ways to maximise apprentices' professional learning and workplace contribution. Overall, the study highlights the importance of engaging all stakeholders in workplace-based learning apprenticeships and clarifying the value proposition for each stakeholder to increase engagement and promote useful conversations between them. The article discusses the challenges in translating theoretical learning into practical workplace applications for apprentices at the higher education level. The main limitations of the study include its small, person-centred online collaborative set within a new working relationship. Although the potential political dimensions were acknowledged, no obvious power differences were observed between the stakeholders. The study did not have representation from apprenticeship employers at less advanced stages, which may limit its generalisability and it was limited by the facilitator and practitioner-provider having to remain objective, which may have influenced its outcomes. Several findings link to the paramedic degree apprenticeship, including stakeholder concerns and responsibilities, mentor-mentee concerns, barriers and challenges with assessment and role identity |

Stage 5. Collating, summarising and reporting the results

All studies used a qualitative approach to data collection, using unstructured or semi-structured interviews (n=3), a focus group discussion (n=1), a survey (n=1) or survey combined with semi-structured interviews (n=1).

Of the six studies, Mulkeen et al (2017) and Quew-Jones (2022) were most relevant to the research question. The remaining four studies contribute to the body of evidence.

Braun and Clarke's (2006) method of thematic analysis was used to identify and analyse patterns in the qualitative data. The qualitative data were independently sorted and coded by two members of the research team, with a third team member serving as a thematic auditor.

Preliminary themes were discussed with the research team then grouped within thematic maps. Findings from each theme were integrated and discussed within the context of trends, topics and implications for practice.

Three main themes were identified: the role of the mentor/PEd; stakeholder collaboration; and apprentice learner support, alongside subthemes (Table 4).

| Themes | Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: | Stakeholder collaboration | Saraswat (2016), Mulkeen et al (2017), Roberts et al (2019), Fabian et al (2021), Quew-Jones (2022) |

| Theme 2: | The role of the practice educator | Saraswat (2016), Mulkeen et al (2017), Roberts et al (2019), Smith et al (2020), Quew-Jones (2022) |

| Theme 3: | Apprentice responsibilities and work-life balance | Mulkeen et al (2017), Roberts et al (2019), Smith et al (2020), Fabian et al (2021), Quew-Jones (2022) |

Discussion

Stakeholder collaboration

Saraswat (2016) notes apprenticeships have been associated with manual trades and a lesser academic acumen. This has resulted in a status imbalance between DAs and traditional academic pathways, with apprenticeships often being viewed as a lesser qualification.

It could be argued that the current model of undergraduate education is not sufficient in its present design to address the shortage of skilled labour employers require, with the UK presently having lower levels of labour productivity than the majority of G7 countries (Office for National Statistics, 2023). The NHS long-term workforce plan (NHS England, 2024) highlights how undergraduate educational routes into healthcare roles, such as paramedicine and nursing, have higher attrition rates. DAs offer an opportunity to improve the recruitment and retention of skilled labour on a national scale and to improve shortfalls within underserved communities.

Since 2017, the funding for apprenticeships has been drawn through a levy. Saraswat (2016) notes that larger employers view the levy as favourable and it often produces a return on investment. However, many employers express confusion and alarm at the levy, seeing it as a burdensome ‘tax’ (Mulkeen et al, 2017).

Employers feel a proportion of funding should be redirected towards covering the costs of training PEds and resources required to deliver PBE effectively. Mulkeen et al (2017) highlighted how employers often felt a true representation of the associated costs of DAs were obscured. There is a lack of clarity around funding rules, as well as the cost of workplace education for these learners, which redirects resources from core business activities. The NHS long term workforce plan (NHS England, 2024) resolves this by creating a bespoke levy funding model that can provide greater scope for decision-makers to support employers more effectively according to their specific needs, although this financial forecast is not yet available.

Employers have a key role in the development of DA curricula. Trailblazer groups of employers, higher education institutions (HEIs) and governing bodies decide the KSBs that underpin constructive alignment and the end point assessment (EPA) objectives (Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education, 2023). This approach allows the curriculum to be shaped to meet the employer's needs (Quew-Jones, 2022).

However, many employers feel they may lack the specific understanding and skills to design academic programmes and, in some cases, are likely to defer to academics (Mulkeen et al, 2017). This raises concern regarding collaboration between HEIs and employers as guidance is limited (Quew-Jones, 2022). This is the main stakeholder barrier relating to DAs and their implementation.

Role of the practice educator

Within a DA, PBE is a key component and it includes processes to support apprentice learners in both academic and workplace learning. Each learner is provided with a workplace PEd and a university personal tutor and has an agreed tripartite learning plan (Basit et al, 2015). At the end of the DA, an EPA is completed by the PEd to assess whether the apprentice has gained full competence and ability (QAA, 2019). However, Saraswat (2016) identifies that the assessment strategy varies depending on mentors' expectations and interpretation of the standards. This is identified as one of the main barriers within DA PBE. The subjective interpretation of the ‘independent’ status in relation to KSB competency may be because PEds have experience of undergraduate competencies but this is compounded with a lack of understanding regarding DA requirements.

The focus of PBE is the translation of theory to practice. However, Quew-Jones (2022) and Fabian et al (2021) suggest that most difficulties lie within the PEd not having an understanding of the apprentice's current level of ability and knowledge, or their facilitation of learning not being strategically aligned to the apprentice's current level of academic education. If the PEd has a different interpretation of the KSBs to be attained, and the current standard of apprentice competency differs, this can lead to unrealistic expectations and a breakdown in the mentor-mentee relationship (Saraswat, 2016). To negate this miscommunication, Quew-Jones (2022) suggests devoting time for PEds and apprentices so they can have regular and relevant communication regarding progression through the DA. However, this can be problematic if an apprentice does not have a regular PEd, and instead is allocated to multiple mentors, negating opportunities for debriefing and open discussion. This results in mentor-mentee relationship breakdown, miscommunication and unrealistic or overcompensated expectations placed upon the learner.

Roberts et al (2019) suggested that the relationship between mentor and mentee is critical. An ideal alliance must demonstrate mutual respect, joint learning, and mentoring and teaching aligned with the mentee's academic level. Distributive mentorship, by way of a co-creation and facilitation of learning and problemsolving, would be more beneficial as the apprentice is well established within the organisation, with their own experiences and time served.

Both Roberts et al (2019) and Quew-Jones (2022) identify that it is important to consider motivation to mentor when determining who mentors an apprentice. Unless the PEd is motivated and engaged with the progression of the apprentice, a positive experience and facilitation of learning will not occur. This leads to poor learner experience, dissatisfaction and lack of engagement within the DA programme. To overcome this barrier within PBE, a PEd must be able to adapt their mentorship techniques to apprentice learners and have the motivation to continue this through the apprentice's journey on the programme.

Mulkeen et al (2017) suggested that education and support for PEds are essential if they are to support the new form of working within DAs. This is because PEds need to provide a higher level of academic input for adequate PBE and facilitation than before to ensure learners develop the knowledge and skills required.

This is especially important if PEds are not educated to the same level the apprentice will be when they finish the programme. Apprentices have baseline underpinning theoretical knowledge and, on completion of the DA, have acquired the necessary KSBs for their new role. These may be at a higher standard than those held by some PEds acting as mentors.

Nonetheless, apprentices must be provided with the skills required for constructing their own professional identity and responsibility for self-development. This responsibility is lifelong and is the fundamental philosophy of an apprenticeship (Quew-Jones, 2022).

Robert et al (2019) suggest that the co-creation of the apprentice's journey through their programme affects the development of not only the apprentice but also the mentor. Therefore, employers must provide the necessary education for PEds to support the facilitation of nontechnical skills. This can be done by providing education on the additional mentorship needs of apprentices to ensure the PEd understands their role and responsibility within the development of such skills.

Apprentice responsibilities and work-life balance

Fabian et al (2021) distinguished DAs from a part-time degree by highlighting that apprentices undertake a sizeable portion of their course in the workplace through PBE and are expected to engage in alternating periods of workplace employment and studying with an HEI. This results in the apprentice becoming the central piece for communication within the tripartite relationship.

Mulkeen et al (2017) outlined the how the responsibilities of the employer to monitor skills and competencies contrast with the HEI's responsibility for academic knowledge. The apprentices' responsibilities are studying, taking responsibility for their own self-development, progressing towards the professional standard, fulfilling requirements of the apprenticeship and meeting standards set by HEIs through time management and effective communication with both (Fabian et al, 2021; Quew-Jones, 2022). However, Roberts et al (2019) places the emphasis on the employer to develop emotional intelligence and identify issues requiring management intervention.

Collaboration within PBE can be difficult because of a lack of communication between tripartite group members. Valuable information regarding course requirements, employment demands and learner needs, such as those around specific learning differences and associated action plans, need to be made available to all parties. Constant employer engagement is necessary, alongside the apprentice's role in working with mentors, to ensure PBE is effective and ensures meaningful work-study integration (Smith et al, 2020). This puts the onus of communication between the PBE and HEI on the apprentice, which can challenge the tripartite relationship if not managed effectively.

Quew-Jones (2022) and Smith et al (2020) found that imposter syndrome is common among apprentices. These apprentices face a unique challenge because they are both employees and students at the same time. This dual role leads to a slower development process for them, partly because their employers emphasise the importance of including diverse perspectives and backgrounds, including those without traditional academic achievements. Following apprentices' gradual academic success, Fabian et al (2021) recognised their personal and professional identities evolve from a combination of enhanced self-confidence and deeper theoretical understanding.

Quew-Jones (2022) recommended HEIs support learners to develop their professional identity by encouraging responsibility for their own self-efficacy and increasing their awareness of their professional standards. Fabian et al (2021) and Smith et al (2020) argued that the employer, alongside the degree, enables career progress through demonstration of example career trajectories, opportunities for reflection and transferable skills which can be used outside the workplace.

According to Fabian et al (2021), apprentices are expected to undergo a professional change of identity which is likely to influence their personal identity. Smith et al (2020) discovered apprentices said their main challenge was balancing the simultaneous demands of work and study while also retaining a personal life. Learners may prioritise their academic studies over their personal life, potentially impacting their work-life balance (Mulkeen et al, 2017). However, Smith et al (2020) suggested most apprentices feel supported by employers so were able to find ways to manage the demands of work, study and personal life.

Furthermore, Fabian et al (2021) acknowledged apprentices already valued contributor status within their organisation so feel obliged to catch up with work missed through spending time at university. Smith et al (2020) found learners had no time within their working hours to study but most employers created strategies to help, including setting aside time during working hours. In theory, because of the nature of the demand from ambulance services and lack of formal deadlines, this should not be an issue as learners could be abstracted from shifts. However, learners are faced with operational and rostering limitations where they struggle to fulfil their minimum requirement of off-the-job hours because of staff and mentor shortages (Fabian et al, 2021).

An apprenticeship is not simply an accreditation of work experience or a qualification that can simply be completed during evenings and weekends, but must be a true partnership between apprentice, employer and university.

Limitations

Although the use of a structured methodology for literature searching adds strength and validity to this review, there are limitations to the breadth of the search completed. For example, this review used research covering other professions and academic levels, which could affect the generalisability of the results.

The paucity of research on paramedic DAs limits the ability to draw strong conclusions. However, the purpose of this scoping review allows for information to be drawn from other professions which could be applied to paramedic practice, informing the direction of this research.

Conclusion

The objective of this scoping review was to identify barriers and challenges in terms of PBE involved in paramedic DA. Several key issues were identified surrounding PBE from the different stakeholders' perspectives.

This review notes that employers have a key purpose in the collaborative design of DA, yet multiple issues in terms of collaboration exist. This extends not only from the design and structure of curricula, but also into the administration and funding rules, which permeate and underpin the apprenticeship model in all professional disciplines. Paramedic education is therefore not immune to these combined barriers, particularly when considering the multiple trailblazer groups, institutions and trusts that manage paramedic DA education and have their own often-competing needs and requirements.

Another key barrier identified was the interpretation of apprenticeship-specific terminology used to assess learners' competence and the subjective definition of expected standards. Without knowledge of DA and having only undergraduate programmes as a basis of understanding, PEds have the additional challenge of accurately assessing apprentices' competencies within the work environment. Emphasis must be placed on shared awareness of progression through the DA programme, with consistent communication within the mentor-mentee relationship. The PEd must be motivated to mentor the apprentice, and employers must provide the necessary education for PEds so they can support the facilitation of learning and assessment within the PBE environment adequately.

The final barrier discussed in this paper was learners achieving a healthy work-life-study balance and their developing sense of identity and responsibility throughout the DA. Responsibilities relating to apprentice success lie equally with the employer and the individual learner through effective communication, time management and recognition of any shortcomings. Imposter syndrome is prevalent among apprentices and employers need be aware their development will be gradual to ensure success and learner wellbeing. This can only be achieved through employers making arrangements to ensure learners have enough time to complete their studies and for leisure in addition to any work obligations. The apprentice's work-life balance must be considered appropriately to ensure adequate time is available to complete their programme requirements.

This scoping review goes some way to demonstrate that more research on each stakeholder barrier identified is needed, as well as clearer guidance for employers regarding funding and expectations and improved education and support for PEd's to facilitate their role within the apprentices' PBE.

Qualitative research surrounding apprentice feedback and suggestions for change are required, alongside PEds' critical viewpoints to enable change and adaptation to current practice for improved PBE for apprentice learners.