A number of articles have recently been published regarding the use of social media by paramedics (College of Paramedics, 2015; Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), 2017; Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2019; College of Paramedics, 2019; Cotton et al, 2019; Mallinson, 2019; Smith et al, 2019); however, none have included a comprehensive analysis of the legalities of social media use by health professionals.

The present article therefore will seek to explicate the legal position of ambulance service social media use and its potential to impinge on the fundamental human rights of ambulance service users, which in its essence may diminish the eons-old ethic of confidentiality and trust associated with the ‘doctor-patient relationship’ and thus cause real harm to individual patients, paramedics and the paramedic profession.

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Article 10, which came into UK law in the Human Rights Act 1998, gives us all the right to express ourselves and our views in our own way:

‘Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers.’

Thus, freedom of expression, as a human right, extends to all paramedics and health professionals and their use of social media to express their thoughts and ideas without interference from the state. The state includes any public authority, which all NHS ambulance trusts, and private organisations performing NHS functions undoubtedly are (House of Lords, 2003).

However, this right is not absolute or without limits; for example, the Public Order Act 1986, 18 (1) criminalises speech, written material or other communications that may insight racial hatred. This provision thereby allows the state to lawfully limit a racist thinker's freedom to express such ideas publicly. Therefore, although we have rights, there is a legal obligation for us to use those rights responsibly.

An example of the way in which those who use social media are held to account for their publications is the case McAlpine v Bercow [2013]. In this case, Sally Bercow, the wife of the House of Commons Speaker, John Bercow, tweeted:

‘Why is Lord McAlpine trending? *Innocent face’

At the time, Lord McAlpine had been wrongly and maliciously implicated as a paedophile (Greenslade, 2014). Upon discovering Mrs Bercow's tweet, Lord McAlpine commenced legal action against her for defamation. In a defamation matter, the claimant must prove that the defendant [Mrs Bercow], ‘(1) refer[s] to that claimant and (2) they substantially affect in an adverse manner the attitude of other people towards the claimant, or have a tendency so to do.’ (McApline v Bercow [2013] para 36).

From this single seven-word tweet expressed by Mrs Bercow, the Judge, Mr Justice Tugendhat, found that ‘…the Tweet meant, in its natural and ordinary defamatory meaning, that the Claimant was a paedophile who was guilty of sexually abusing boys living in care.’ (McApline v Bercow [2013] para 90). Mrs Bercow settled with a payment of damages reported at £15 000 (Dutta, 2013). It is important to note that in human rights law, there are often competing interests and rights that must be considered. In the case of the use of social media, the right that competes with ‘freedom of expression’ is the ‘right of privacy.’

The implications for paramedics utilising social media as part of their role, or indeed anyone using social media, is that they must be extremely careful to ensure their actions are responsible and lawful. As noted, the ‘right to privacy’ (found in Article 8 of the Human Rights Act 1998) is a right that must be upheld by all social media users. This applies particularly to paramedics because respecting the patient's privacy is essential to gaining the patient's trust in order to perform the job. Although paramedics, as individuals, have the right to express themselves publicly, when using social media on behalf of their public organisations, the ‘corporate tweeter’, as they have become known (AACE, 2019), must not interfere with the human rights of their service user; in this case, the service user's right to a private and family life which is protected by law.

The human right to privacy law states:

‘1 Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and his correspondence. 2 There shall be no interference by a public authority with the exercise of this right except such as is in accordance with the law and is necessary in a democratic society…’

Cotton et al (2019) contend that promoting the work of their various ambulance services is a ‘compelling reason’ for corporate tweeting and that they have a ‘statutory duty to engage with the public.’ Cotton et al (2019) provide no reference for the legislation, and it should be noted that no legislation can be enacted that unlawfully allows an infringement of an individual's human rights. Thus, any social media use which potentially infringes article 8 would be unlawful; however, even if there were a ‘statutory duty to engage the public’, there are numerous ways in which the ambulance services can do this without breaching the privacy or confidence of their patients.

Cotton et al (2019) do acknowledge that the confidentiality of patients must not be broken; however, they go on to suggest that live tweeting from a scene attended by paramedics is ‘acceptable’ because the HCPC has told the authors that ‘as long as staff had completed their clinical care, they had no issue with them tweeting’ (Cotton et al, 2019). This privately made statement only draws inference from the regulator and cannot be taken as a form of approval, notwithstanding the guidance on social media use published by the HCPC that says that paramedics should ‘keep on posting’ (HCPC, 2017).

The HCPC (2018) Standards of Conduct Performance and Ethics begin with ‘Promote and protect the interests of service users and carers’ and ‘You must treat service users and carers as individuals, respecting their privacy and dignity’. Therefore, in instances where social media use breaches those standards, the HCPC has a statutory duty to investigate (Health Professions Order, 2001). In fact, they have done so on several occasions (Health Care Professions Tribunal Service (HCPTS) v Blight [2017]; HCPTS v Weinbren [2019]), with a reported 1200 disciplinary actions against healthcare staff between 2013 and 2018—62 of those cases arising from Yorkshire Ambulance Service alone (Lay, 2018).

What constitutes privacy and where duties of confidence arise, was discussed in the case Campbell v Mirror Group Newspapers (MGN) Ltd [2004]. In this case, supermodel, Naomi Campbell, was pictured leaving a Narcotics Anonymous meeting after having denied she was suffering from drug addiction. Baroness Hale, now President of the UK Supreme Court, stated:

‘It has always been accepted that information about a person's health and treatment for ill-health is both private and confidential. This stems not only from the confidentiality of the doctor-patient relationship but from the nature of the information itself.’

Baroness Hale goes on to quote a judgment from the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) case Z v Finland [1997]:

‘Respecting the confidentiality of health data is a vital principle in the legal systems of all the Contracting Parties to the Convention. It is crucial not only to respect the sense of privacy of a patient but also to preserve his or her confidence in the medical profession and in the health services in general. Without such protection, those in need of medical assistance may be deterred from revealing such information of a personal and intimate nature as may be necessary in order to receive appropriate treatment and, even, from seeking such assistance, thereby endangering their own health and, in the case of transmissible diseases, that of the community.’

Hale's decision incorporates into law the eons-old ethical principle of doctor-patient (or paramedic-patient) confidentiality, which was first espoused in the Hippocratic Oath ‘to maintain confidentiality and never to gossip’ and applied today as ‘what [a health professional] may see or hear in the course of treatment or even outside of the treatment in regard to the life of [patients]… [they] will keep to [themselves].’

In another case involving the publication of medical information about the serial child killer Ian Brady, the then Master of the Rolls, Lord Phillips MR, stated:

‘… in my view when a patient enters a hospital for treatment, whether he be a model citizen or murderer, he is entitled to be confident that details about his condition and treatment remain between himself and those who treat him. Furthermore, there must be a subjective element as to what any one patient would consider so personal that he would not wish it to be divulged.’

In other words, every person, regardless of the view of that person's character or circumstance by another, is protected by the law. It is not a matter for anyone but the patient to share their private information with anyone. The patient may consent to paramedics or ambulance services using this private information for the paramedic or ambulance services' benefit, but it is only with the patient's consent that this sharing of patient information is lawful. ‘Storytelling’ as Cotton et al (2019) call it, is not an acceptable use of patient data when it is not their story to tell, but their patient's.

In Smith's (2019) article, he highlights his concerns about the negativity of responses to tweets which he classifies as ‘positive work-related posts.’ Smith is suggesting is that there have been occasions when tweets he has determined to be ‘positive’ have been challenged by conscientious and professional paramedics or others, who have deemed them ‘negative’ and that this disagreement is simply a difference of opinion. However, this attempt to relativise the problem, that is, to suggest that your opinion is no more ‘right’ than mine, is to suggest that there is no fact in the matter (Townsend and Luck, 2019). There are standards, policies and indeed laws that establish what is acceptable information for paramedics to share with others. It is not merely a matter of opinion—these standards are matters of law and, therefore, fact.

Baron and Townsend (2017) highlighted issues with corporate tweeting in this very journal arguing that some corporate tweeting was crossing the line into a breach of professional standards by actions such as tweeting photos from scene, tweeting demographic patient data such as the age of the patient and location of the incident, and even tweeting from scene while the incident was ongoing—all activities which could constitute a breach of the privacy laws.

Conversely, not every minor breach of confidentiality will lead to direct harm and Baroness Hale in Campbell also noted that:

‘Not every statement about a person's health will carry the badge of confidentiality or risk doing harm to that person's physical or moral integrity. The privacy interest in the fact that a public figure has a cold or a broken leg is unlikely to be strong enough to justify restricting the press's freedom to report it. What harm could it possibly do?’

A free press is also a fundamental right in a free and democratic society (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2016); nevertheless, Cotton et al (2019) and Smith (2019) are not representing the free press, which has its own code of practice and ethical guidelines (Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO), 2019). They are representatives of ambulance services and NHS organisations that have no duty to report news and are held to different—and arguably more stringent—legal and ethical standards. Notwithstanding this, it appears that some trusts have conflated their duties with a news reporting role; for example, West Midlands Ambulance Service (WMAS) have a dedicated page for news, complete with various pictures on their website and headlines including ‘Fatal Crash’ and ‘Damage left over 150 yards’ (WMAS, 2019).

Smith (2019) believes that ambulance services ‘don't have the option of holding information or issuing statements hours after an incident has occurred: news nowadays is instant, and so must be our response to the media.’ It may be the case that news is instant, but news still reports public interest stories and Smith's (2019) opinion does not justify the tweeting of non-public interest cases. There have been occasions where Twitter use by health services has been shown to be helpful to inform the public, such as during major emergencies like terrorism (Baron and Townsend, 2017; Cotton et al, 2019); however, these are uncommon and extreme examples and by no means imply that everyday incidents need to be reported by health services. Tweeting of these events might be considered appropriate ‘engagement with the public.’ Providing health information of a patient or patients would not (Baron and Townsend, 2017).

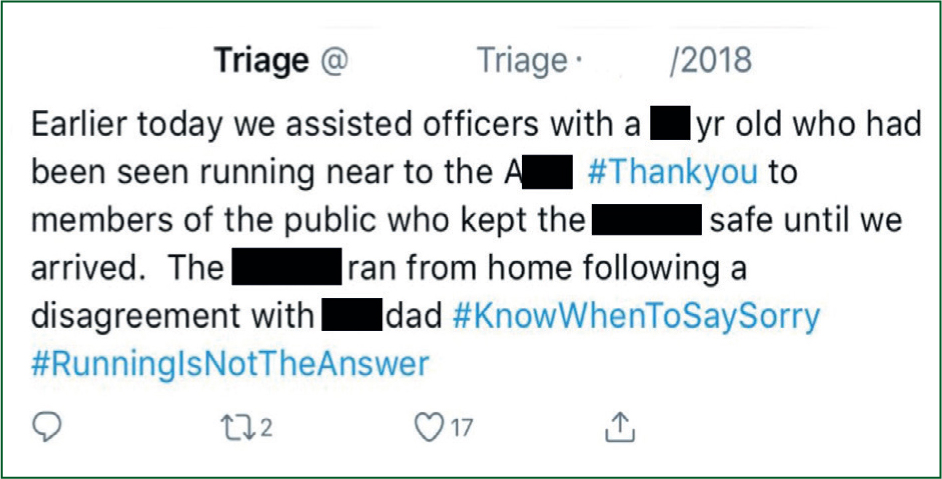

The HCPC supports the use of social media and highlights a number of benefits of social media use (HCPC, 2017); but Baron and Townsend (2017) argue that ‘benefits’ such as public education or promoting the profession only have a legitimate foundation if they do not exploit patients as a means to an end. Indeed, the author has encountered several tweets, such as the example in Figure 1, which breaches professional standards and the ‘Intention to Tweet Matrix’ advised by Baron and Townsend (2017) that proposes a basis for safe tweeting by health professionals. The tweet in Figure 1 is deeply concerning for several reasons.

The tweet contains sufficient data for the child and their family to identify themselves. It is tweeted the same day, with the location, age and sex of the child. It is also wholly judgemental, with hashtags making this a public shaming and cyber bullying by a public body of a child due to the significant power imbalance (Smith, 2016)—activities which a recent House of Commons report has shown to have a significant impact on children's mental health and wellbeing (House of Commons, 2019). The author submits that this is not only a breach of professional standards, but also a potential breach of a child's Article 8 right to a private and family life by a public organisation that not only has an statutory duty to uphold their human rights, but also protect and safeguard a child's wellbeing as they are one of society's most vulnerable groups.

Other kinds of tweets may appear to be perfectly innocent and harmless but could have an insidious potential to cause harm. The tweet in Figure 2 is, on the face of it, an innocent celebration of new life and a happy occasion; however, by showing the face of mother and child and giving the baby's name, the family in this picture are fully identifiable. The Baron and Townsend (2017) Decision to Tweet Matrix suggests that tweets posted for promotion of one's account or their employers are exploitative and, furthermore, those containing pictures from scene or the exact dates and times of incidents should not be tweeted. Tweeting such pictures from scene or incidents involving patients also raises issues for health professionals, particularly in the areas of power and consent. The tweeter in Figure 2 may argue that the tweet was acceptable as they obtained consent from the mother for the photo; however, consent is a more profound concept than gaining a nod of the head. Herring (2008) explains that consent has three elements which must be proved for it to be considered valid:

Bester et al (2016) argue that cognitive overload and emotions can contribute to reductions in the capacity to consent and can thereby lead to ‘cognitive overwhelm’ for patients. It could therefore be argued that the emotional burden of birth may alter the patient's ability to consent due to her emotional state. Also, what do the tweeters classify as sufficient information to inform? What information was given to the mother before the photo was taken to ensure the consent was informed? Does she fully understand the nature of Twitter? Does she know she has the right to ask for the removal of the photo? What is the procedure for the removal of tweets at the patient's request down the line?

Furthermore, the vulnerability of the patient in this tweet could potentially invalidate the ‘consent’. Nimmon and Stenfors-Hayes (2016) expound the nature of power and argue that any interaction between patients and health professionals is subject to a power dynamic. The tweeter was already in a position of power over the patient, and it could be therefore argued that by requesting the photo, the paramedic was exerting undue influence over the mother—especially as the mother may feel grateful or otherwise indebted to the health professional who assisted with the birth of her child.

The ECtHR has also found that the release of images can be a grossly disproportionate breach of privacy. In Peck v United Kingdom [2003], a man suffering from a mental illness was captured on CCTV in public carrying a large knife with intent to commit suicide. The CCTV images were then shown on a TV show with the man's facial image blurred. The court found that:

‘…the relevant moment was viewed to an extent which far exceeded any exposure to a passer-by or to security observation and to a degree surpassing that which the applicant could possibly have foreseen when he walked along the High Street. Accordingly, the disclosure constituted a serious interference with the applicant's right to respect for his private life.’

In conclusion, everyone has the freedom of expression and there may be occasions where corporate tweeting is appropriate and safe; however, it has been demonstrated that the courts take breaches of privacy very seriously and, occasionally, these have constituted an interference with the patient's Article 8 human rights to a private and family life. First and foremost, a health professional's duty involves acting in their patient's best interests and this includes protecting their right to privacy. Ambulance services have been shown to have a legal duty to protect the privacy and confidentiality of their patients, which has been a fundamental tenet of good medical practice since 500 BC.

The consequences of breaches by public organisations could be expensive litigation; however, more worryingly, inappropriately tweeting about patients can put them at risk of harm. Tweets have on occasions amounted to the public shaming or cyber bullying of children, while the tweeting of images of patients or scenes of incidents is fraught with legal and ethical risks.

Even if ambulance services have ‘a duty to inform,’ there is no legal exception that allows them to breach the provisions of the Human Rights Act 1998. Paramedics looking for guidance on what their professional responsibilities are with regard to the lawful and ethical use of social media should read the HCPC guidelines and consider using the Baron-Townsend Decision to Tweet Matrix.