There are few instances within the realm of musculoskeletal trauma where paramedics can have such a profound impact on the care of their patients as in the case of the acutely dislocated knee. Although uncommon, the multiligament injured knee or dislocated knee has the potential to become a very serious limb threatening injury. These injuries are often subtle and require a meticulous and targeted history-taking and examination to detect. Failure to identify and appropriately treat these injuries in a timely fashion can have catastrophic results. In seeking pathology rather than assuming wellness, an occult, limb-threatening injury can be detected, and in the process, a limb saved.

Definition

Knee dislocation is a descriptive term that belies the complexity of the injured state that it represents. It is better understood as a complete disruption of the articulation of the tibia and the femur, significant enough to potentially injure the nervous, vascular, and ligamentous structures of the lower limb. Early classification schema for knee dislocations were based on the position of the tibia relative to the femur in the dislocated state (Kennedy, 1963). This system was not useful because a spontaneous reduction of the dislocation occurs in 50% of cases, thereby masking the true severity of the injury (Wascher et al, 1997).

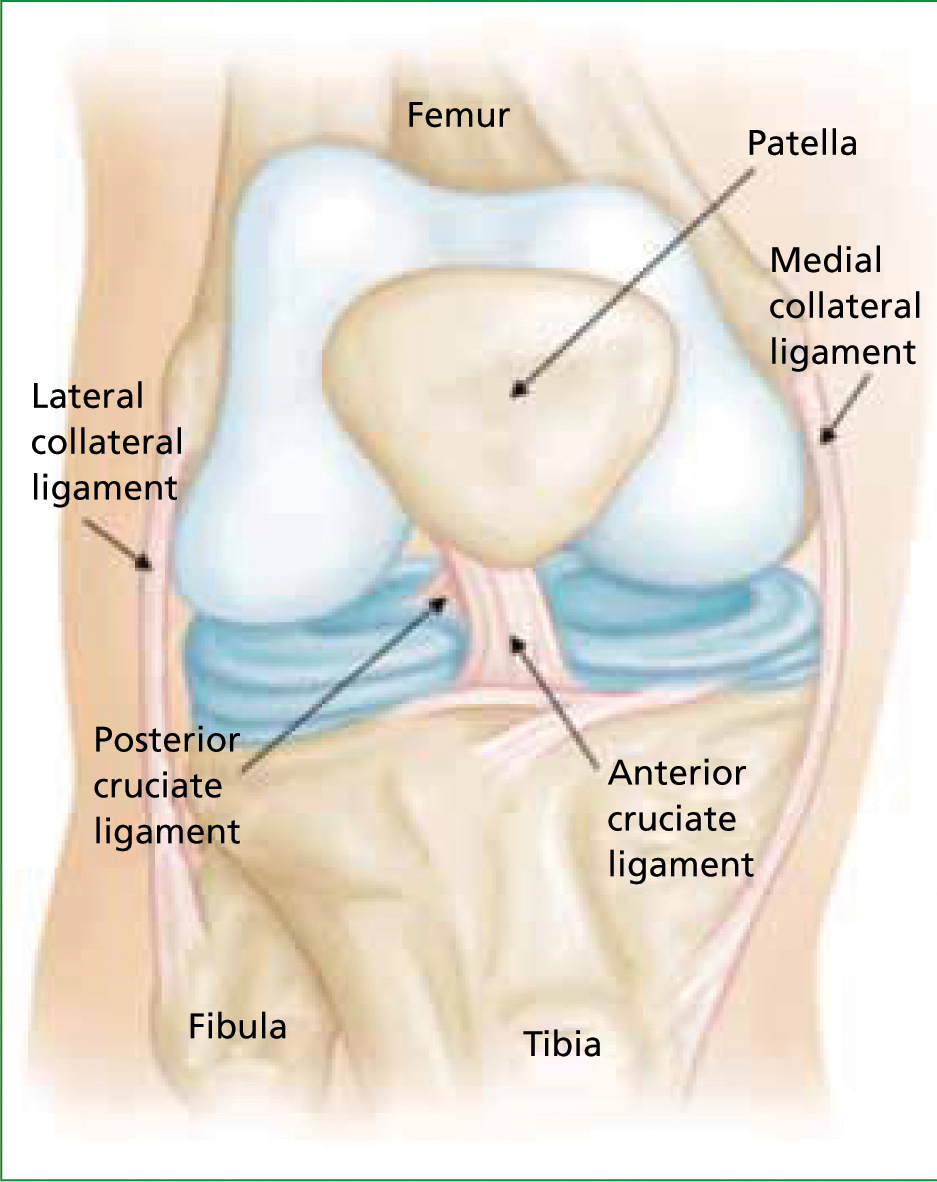

In considering this, others redefined knee dislocation with an anatomic classification system that relied on the pattern of ligamentous disruption to describe the injury, identifying the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL), and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) as the primary ligaments that stabilize the knee joint (Schenck, 2003). In this system, knee dislocations are classified in the following manner:

Although knee dislocations most commonly involve disruption of both the ACL and PCL (KD II, III, IV, V), dislocation can occur with only single cruciate disruption (KD I) (Meyers et al, 1975; Schenck, 2003). The association of potentially serious neurologic and vascular injuries with knee dislocation is well known. Its association with the multiligament disrupted knee is perhaps less well known but no less potentially catastrophic. For this reason, paramedics should view these injuries in a broader sense, with the aim of identifying those knees which have sustained serious injury so as to have potentially disrupted ligaments, vessels, and nerves, rather than focusing on whether or not the knee ever truly dislocated.

Anatomy

The ACL and the PCL are two knee ligaments that cross between the tibia and the femur within the joint at the center of the knee. These ligaments provide the majority of anterior and posterior stability to the knee. The collateral ligaments on the medial and lateral sides of the knee assist with side-to-side stability (Figure 1). The lateral and posterolateral aspect of the knee contain many ligaments and tendons that contribute to rotational stability of the knee. In a knee dislocation, any of these ligaments can be injured.

Major nerves and vessels pass in close proximity to the knee and can be injured during a knee dislocation. The popliteal artery is the single predominant inflow vessel for the lower leg in nearly all cases, dividing into three major branches only after passing behind the knee in 91% of cases (Kropman et al, 2011). Among US causalities in World War II, serious injury to the popliteal artery resulted in amputation in 72.5% of cases, the highest for any major vessel, a testament to its dominance in providing inflow to the lower leg (Debakey and Simeone, 1946).

In a recent review of the US National Trauma Databank from 2002 to 2006, injury to the popliteal artery was associated with the highest risk of limb amputation at 9.7% (Kauvar et al, 2011). The anatomy of popliteal artery as it crosses behind the knee plays a significant role in its vulnerability to injury during knee dislocation. The popliteal artery resides in close proximity to the posterior tibial cortex throughout it course, as close as 1.8 mm from the tibia with the knee in full extension according to one study in healthy male volunteers (Smith et al, 1999; Yoo and Chang, 2009). It is tethered proximally as it crosses through the adductor magnus muscle, and then again distally at the point of its division into branches. The unfortunate combination of its proximity to posterior tibial cortex and its relative immobility put the popliteal artery at risk during knee dislocation.

The most commonly injured nerve in knee dislocations is the common peroneal (fibular) nerve. This nerve is one of two major branches of the sciatic nerve which split from one another in the posterior aspect of the distal thigh, the other being the tibial nerve. The peroneal nerve travels around the lateral side of the knee in a subcutaneous location around the neck of the fibula, where it divides its two branches, the superficial and deep peroneal nerves. These nerves provide motor innervation to the anterior and lateral compartments of the lower leg. The peroneal nerve is at risk of injury both by direct trauma from impact owing to its superficial location and also by stretch injury during knee dislocation. Motor functions allowed by these nerves include ankle dorsiflexion, ankle eversion, and toe extension. Sensory innervation to the dorsum of the foot is provided by the superficial peroneal nerve, and to the dorsal web space between the first and second toes by the deep peroneal nerve.

Epidemiology

Knee dislocations represent less than 0.2% of orthopaedic injuries presenting to the emergency department (Hoover, 1961; Kennedy, 1963; Brautigan and Johnson, 2000; Robertson et al, 2006; Peltola et al, 2009). A high-energy mechanism is usually observed in these injuries, with motor vehicle collisions, pedestrian vs vehicle impacts, and falls from height being the most common (Kennedy, 1963; Hagino et al, 1998; Brautigan and Johnson, 2000).

Data from the authors’ institution, a single tertiary referral academic center in the US, includes 138 multiligament knee injuries, of which 81 (59%) were the result of a high-energy mechanism of injury, and 57 (41%) were the result of a low-energy mechanism, with 48 of those (84%) having been sustained during athletic activity (Merritt and Wahl, 2011b) (Figure 2). Some have suggested that the trend towards increasing strength and size of athletes in collision sports has increased the number of knee dislocations seen in association with athletic activities (McCoy et al, 1987; Brautigan and Johnson, 2000). Spontaneous knee dislocation has also been described in association with morbid (BMI > 35) and super morbid (BMI > 45) obesity and low energy mechanism of injury. Among reported cases, dislocation occurred due to ground level fall, ambulation on level ground, or when arising from a chair (Hagino et al, 1998; Seenath et al, 2003; Shetty et al, 2005; Peltola et al, 2009).

Field assessment

Visual exam

The first step towards ensuring appropriate care for the injured extremity is to identify it. This begins with a systematic and meticulous physical examination. Visual inspection of the limb can provide many clues to suggest a multiligament knee injury. Pallor or cyanosis of the limb can indicate a vascular injury, but these are typically late findings that may not be present at initial assessment. Large ecchymoses around the knee or of the lower leg can be a clue to a vascular injury or haemarthrosis, both indicators of a potentially serious limb injury. A limb that appears grossly deformed due to an unreduced knee dislocation should be readily identified and promptly reduced. An irreducible knee dislocation is a surgical emergency.

Open fractures and traumatic arthrotomies are evidence of violent trauma to the leg that could have resulted in multiligament disruption, nerve or major vessel injury. Although uncommon, open injuries demand more urgent attention because of higher risks of infection, neurologic and vascular injury, and the need for urgent surgical management. Open injuries occur in 19 to 35% of all multiligament knee injuries (Meyers et al, 1975; King et al, 2009). Vascular injuries occurred in 5 of 19 (26%) open knee dislocations, and neurologic injuries in 7 of 19 (37%) in one series (Wright et al, 1995).

Palpation

Palpation of the injured extremity is equally of value in the initial assessment. A tense, swollen knee joint may represent an acute haemarthrosis, which has a strong association with intraarticular fracture or cruciate ligament tear, both of which can occur in the setting of multiligament injury. If the knee is noted to be grossly unstable when handling or moving the leg, this can also be a strong indication of a serious ligamentous disruption or dislocation event.

Vascular exam

Palpation of the femoral, dorsalis pedis, popliteal and posterior tibialis artery pulses should be performed for every suspected knee dislocation. The femoral artery pulse can be palpated in the inguinal crease, at the midpoint between the anterior superior iliac spine and the midline of the body. The popliteal artery is challenging to palpate, but can be attempted by placing the examiner's fingers behind the knee and pressing deeply in the popliteal fossa while gently lifting the leg and allowing the knee to bend slightly. The dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses should be palpable in all individuals. The dorsalis pedis pulse can be felt at the dorsum of the foot, just lateral to the extensor hallucis longus (EHL) tendon, the main extensor tendon of the great toe. The posterior tibialis artery pulse is palpable by placing the examiner's finger in the depression just behind the medial malleolus and pressing firmly.

The inability to palpate a pulse in the foot should raise concern for a vascular injury proximal to this level. However, pulse palpation alone is an unreliable exam. Pulses may not be palpable for reasons other than vascular injury, such as soft tissue swelling in the area being palpated, large body habitus, or longstanding peripheral vascular disease. Perhaps more importantly, the opposite may be true, in that distal pulses may be palpable despite a complete occlusion of the artery more proximally in the leg. This can be possible because of collateral flow or because the vascular injury has not caused a complete occlusion.

These non-occlusive injuries do not initially cause complete disruption of the flow of blood through an artery, but leave the artery at risk of later occlusion. Multiple reports have identified cases of normal pedal pulses in the setting of such injuries that later evolved into limb-threatening vascular injuries (McCoy et al, 1987; Rose and Moore, 1988; McCutchan and Gillham, 1989; Lohmann et al, 1990; Gable et al, 1997; Barnes et al, 2002; Mills et al, 2004). It cannot be overemphasized that simply palpating extremity pulses alone should never be taken as evidence that a vascular injury does not exist. Pulse palpation alone is inadequate in the vascular assessment of a traumatized extremity (McCoy et al, 1987; Johansen et al, 1991; Lynch and Johansen, 1991; Gable et al, 1997; Barnes et al, 2002; Mills et al, 2004; Harb et al, 2010; Merritt and Wahl, 2011a).

Not all signs of vascular injury are subtle. The so-called ‘hard signs’ of vascular injury are clear indicators that a significant vascular injury has occurred (Stannard et al, 2004; Nicandri et al, 2009). To the examining surgeon at our institution, ‘hard signs’ of vascular injury will result in patients being taken directly to the operating room for arteriography, surgical exploration, and possibly revascularization. Evidence of distal ischemia in the traumatized limb, manifested as dark, mottled discoloration of the distal extremity is one such finding. A limb that is cool to the touch compared to the uninjured limb is another.

Brisk or pulsatile bleeding from the limb may also indicate disruption of a major arterial vessel, as does a pulsatile or expanding haematoma. Haemostasis should be attempted through direct pressure at the site of bleeding, with tourniquet application being reserved only for cases where pressure alone fails to halt exsanguination. When hard signs of vascular injury are detected, emergent transport to hospital is indicated.

A high-energy mechanism is not necessary for a vascular injury to have occurred. Rather surprisingly, lower energy mechanisms can be associated with a higher risk of vascular injury. This was shown in one series of seven cases involving 4 morbidly obese and 3 super morbidly obese patients where a 100% association with vascular injury was reported despite low energy mechanisms in all (Hagino et al, 1998). For comparison, arterial injury has been reported in 7.5 to 64% of all knee dislocations (Meyers et al, 1975; McCoy et al, 1987; Rios et al, 2003). This is important to remember, for although pulses may be more difficult to palpate in an obese patient, one must not assume the pulse is not palpable due to this alone, thereby missing a very serious vascular injury.

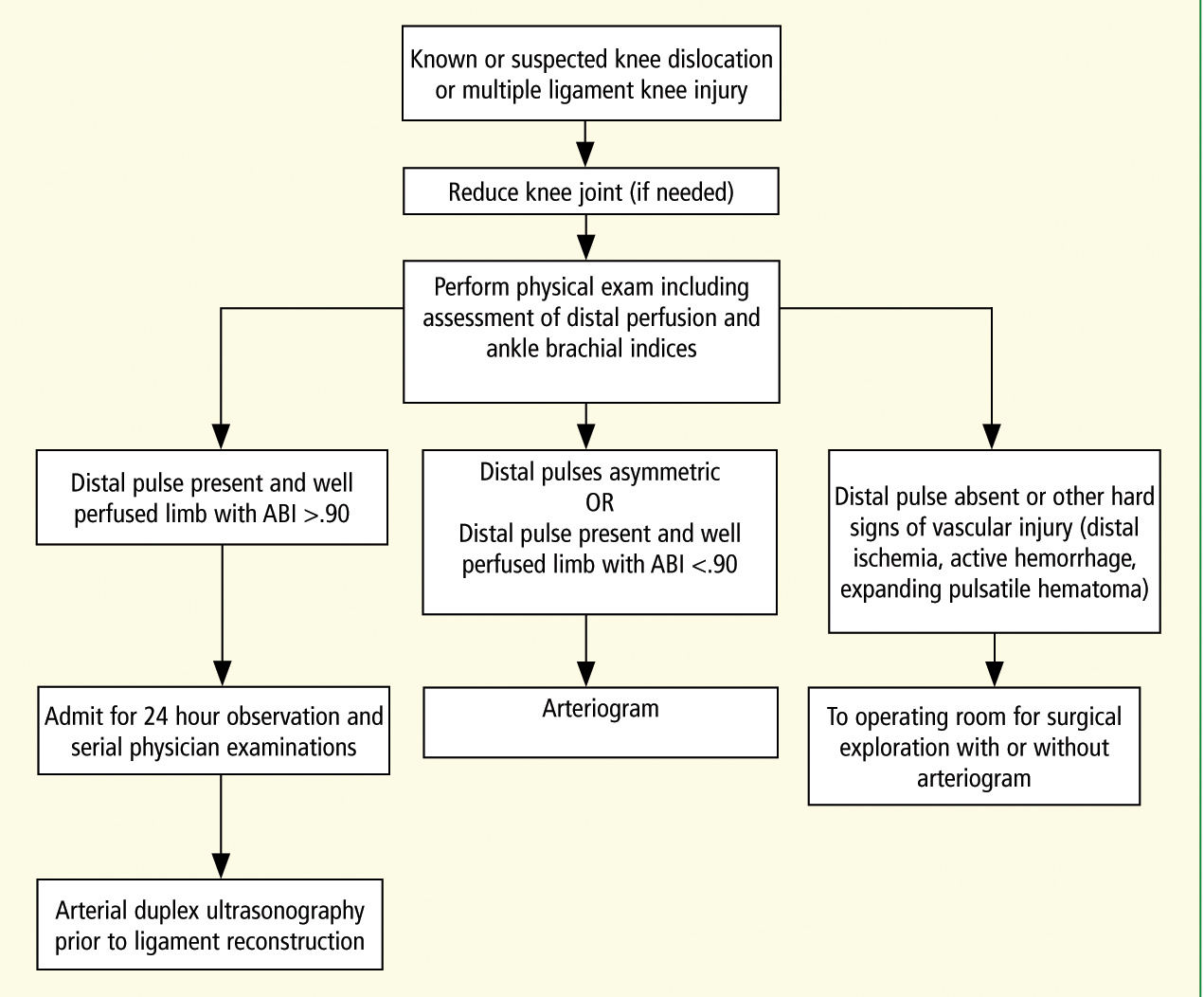

The strong association between knee dislocation and vascular injury makes a complete vascular assessment of the injured extremity a critical necessity. Any known or suspected knee dislocation or multiligament knee injury will require in-hospital assessment, possibly including serial examinations over a period of at least 24 hours, limb pulse pressure measurement, or advanced imaging studies (Figure 3). However, a paramedic's ability to recognize subtle signs of vascular injury can help assure the patient receives appropriate care. The potentially disastrous consequence of missing an occult vascular injury underscores the importance of detecting these injuries early.

Neurologic exam

Weakness or numbness in the traumatized limb should alert the examiner to a potential multiligament knee injury or vascular injury. The common peroneal nerve is the most commonly injured nerve in the setting of a knee dislocation, with a reported incidence of 14 to 25% (Rios et al, 2003; Twaddle et al, 2003; Niall et al, 2005; Lustig et al, 2009). We have found an incidence of common peroneal nerve palsy of 23% among 90 cases of knee dislocation over four years at our institution. Among those with a vascular injury, the incidence was 63% (Merritt and Wahl, 2011a) (Table 1).

| Neurologic status | Vascular status | Number | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| No deficit | No deficit | 65 | 72 |

| Common peroneal palsy | No deficit | 13 | 14 |

| No deficit | Intimal tear or low ABI (no intervention required) | 2 | 2 |

| No deficit | Complete popliteal artery injury | 2 | 2 |

| Common peroneal palsy | Intimal tear or low ABI (no intervention required) | 1 | 1 |

| Common peroneal palsy | Complete popliteal artery injury | 7 | 8 |

| No intervention required indicates that these vascular injuries were managed expectantly and did not require vascular surgery to maintain limb perfusion. | |||

Patients may report sharp, radiating pain in the leg, or numbness in the distribution of the peroneal nerves following such an injury. They may also be unable to extend their toes or their ankle due weakness of the muscles supplied by this nerve. A nerve does not need to be lacerated or torn to cease functioning, as stretch injury alone can result in neuropraxia that impairs the function of a nerve temporarily or permanently. The association of vascular and neurologic injuries is important to note because neurologic deficits may be more obvious during initial examination than the sometimes subtle signs of vascular injury.

Reduction

When identified in the field, a dislocated knee merits at least a single attempt at reduction prior to transfer to the hospital for definitive care. As stated in the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liason Committee (JRCALC) 2006 guidelines:

‘Any dislocation that threatens the neurovascular status of a limb must be treated with some urgency. Such dislocations require prompt reduction.’

Although the guidelines fail to specify by whom the reduction should be performed, in the case of displaced fractures, the recommendations are clear: ‘Consider realignment of grossly deformed fractures into a position that is as close to normal anatomic alignment as possible’ (JRCALC, 2006).

Reduction of the acutely dislocated knee ought to follow the same principles, given the attendant morbidity of delay and the relative ease with which most knee dislocations can be reduced. Reduction can usually be achieved through gentle longitudinal traction on the limb followed by manipulation of the tibia in the direction as to achieve alignment in the sagittal and coronal planes.

With anterior dislocation being most common, a posteriorly directed force on the tibia and an anteriorly directed force applied to the back of the femur may achieve reduction even without traction. Posterolateral knee dislocations can be more challenging to reduce, as in some rare cases, the medial femoral condyle may buttonhole through a rent in the medial knee capsule, thereby entrapping the capsule between the tibial plateau and the femoral condyle within the knee joint. This usually renders the dislocation irreducible by closed means. One may notice a dimple in the skin at the medial joint line on attempted reduction of the skin in such a setting (Figure 4).

If this ‘dimple sign’ is noted on attempted reduction, or if the knee cannot be easily reduced, the patient should be transported immediately to the hospital as an irreducible dislocation of the knee is a surgical emergency that will require reduction in the operating room (Clark 1942; Huang et al, 2000).

The extremity should be immobilized for transport. Advantages include patient comfort, protection of soft tissues from further injury, minimization of soft tissue swelling, and maintenance of reduction in cases where it has occurred. Immobilization should extend sufficiently proximal and distal from the knee to stably hold the extremity, which usually means from mid leg to mid thigh. The knee should placed into slight flexion of approximately 15° to maximize patient comfort and possibly also to allow optimal distal perfusion (Merritt and Wahl, 2011a). This can be easily done by placing a small bump of towels or a saline IV bag behind the thigh prior to application of the immobilizing device (Figure 5).

Patellar dislocation

Dislocation of the patella may be mistaken for dislocation of the knee joint. However, in patellar dislocation, the articulation of the tibia and femur is not disrupted. The average annual incidence of this injury is 5.8 per 100 000 according to one study. 61% of these occurred during sports activity (Fithian et al, 2004). It has been reported to spontaneously reduce in 53% of cases according to one study in Finnish male military conscripts. (Visuri and Maenpaa, 2002). Patients may report the sensation of the knee dislocating, when in fact it was the patella that subluxated over the femur, without any disruption to the tibiofemoral joint having occurred.

Patella dislocation nearly always occurs laterally. A dislocated patella can be easily recognized through palpation of the joint and recognition of the asymmetry to the uninjured leg, with the patella displaced laterally. Though the presence of this injury or any reduction of it must be communicated to caregivers on arrival to hospital, when seen in isolation, it lacks the association with vascular and neurologic injury seen in true knee dislocation as evidenced by a lack of reported cases in the literature. Reduction is achieved by extending the knee while applying a medially directed force to the lateral side of the dislocated patella, guiding it back into the trochlear groove. The knee should then be immobilized in extension for transport.

Importance of communication

It is of critical importance that paramedics who perform a reduction of a dislocated knee ensure that this fact is communicated to caregivers on arrival to hospital. While the severity of injury to the knee may be apparent in the dislocated state, reduction of the joint will obscure this, particularly in the acute setting where swelling and ecchymosis can be minimal despite significant trauma. Paramedics have a unique opportunity to gather important details on the nature of the patient's injuries from witnesses or the patient himself who may recall seeing the knee ‘bent backwards’ or in an otherwise distorted position. Given that some 50% of knee dislocations reduce spontaneously (Wascher et al, 1997), this history may be a significant clue to a serious injury that has otherwise left no obvious deformity. In cases where a patient arrives to hospital unable to give a detailed history of events, either due to the administration of narcotics, loss of consciousness, or otherwise, the details gathered by paramedics on scene are made all the more critical to the care of the patient.

Conclusion

Paramedics can play an important role in the management of multiligament knee injuries and knee dislocations. Prevention of patient morbidity depends on prompt identification and intervention. Because of the association with serious neurologic and vascular compromise, missed injuries pose a very real threat to limb function and viability. With the signs of trouble often being subtle, timely recognition requires that these injuries be specifically sought in every instance of lower extremity trauma.

Careful attention to the details of how the injury was sustained and meticulous physical examination are essential. When recognized, the dislocated knee must be reduced and properly immobilized for transport. The inability to achieve reduction in the field should prompt emergent transport to the hospital. Direct communication with hospital-based caregivers regarding reductions performed in the field or any information suggestive of a knee dislocation gathered on scene is critical in avoiding delays in treatment. Through improved awareness of the seriousness of these injuries, caregivers both in and out of hospital can take steps to ensure patients receive appropriate care.