Approximately 110 000 first strokes and a further 46 000 first transient ischaemic attacks occur in the UK every year (British Heart Foundation and Stroke Association, 2009) (Figure 1). Stroke accounts for 53 000 deaths per year in the UK (British Heart Foundation and Stroke Association, 2009) and in England, 300 000 people live with moderate to severe disability as a result of stroke (National Audit Office, 2005).

Stroke outcomes can be improved by timely care, it is therefore vitally important that the emergency medical services (EMS) are able to recognize the symptoms of suspected stroke and initiate a rapid response. People with suspected stroke should be taken immediately to hospital. Early presentation at hospital provides greater opportunity for time-dependent treatments, such as thrombolysis (European Stroke Organization, 2008).

Up to 70% of all stroke patients obtain first medical contact from the EMS (Kidwell et al, 2000). Studies have shown that activation of the EMS is the single most important factor in the rapid triage and treatment of acute stroke patients (Jones et al, 2009; Hong et al. 2010).

The RESPONSE (rapid emergency stroke pathways: organized systems and education) course was developed to improve the knowledge of ambulance personnel in the identification and treatment of patients with acute stroke. The course is accessed via the internet, completed and evaluated online. Online delivery allows flexibility of access by allowing participants to collapse time and space (Cole, 2000). However, online materials must be appropriately designed to promote learning and engage the learner (Anderson, 2008).

Methods

Search strategy

A literature search was undertaken to inform the development of the course. A search strategy was developed to search Medline from 1966 to 2005, and adapted to search EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, and Cochrane. The titles and abstracts of the articles identified by this search were then reviewed. Additional articles were found by screening journals, citation tracking and hand searching.

Any articles that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria were read in full. Other national guidelines were also reviewed, including the Recognition and Emergency Management of Suspected Stroke and TIA Guidelines (National Pre-hospital Guidelines Group, 2006) and the National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke (ICWPS, 2004).

Included studies related to stroke and positioning, oxygen therapy, blood pressure, body temperature and blood glucose. Studies that were only published as abstracts were excluded because of the limited data that could be extracted.

Data extraction

Two proformas were constructed. One proforma was used to record summary data for each article, including: period of study, participants, country, topic, and methodology of data capture; the second proforma recorded participants’ knowledge on each topic. Subsequently, the course content was developed and pilot tested by the multi-disciplinary steering group for the RESPONSE project. The course content includes:

The course also includes useful web links, animations, a multiple-choice test and an online evaluation. The results of an online evaluation of the RESPONSE course are presented later in this article. The course was advertised through training managers and stroke leads at ambulance trusts across the UK, flyers were distributed at national conferences and the course was also advertised on websites and in magazines. Fifty participants could complete the course at any one time.

Research has suggested that online questionnaires should consist of between 10–15 questions (Harris, 1997). Longer questionnaires are directly and negatively correlated with poor completion (Harris 1997). The online evaluation was made up of twelve questions in total.

The final evaluation questionnaire consisted of five closed questions that asked participants about how they would rate their satisfaction with: the course overall, the method of assessment, the animations, usability and level of content. A further three closed questions asked if the course had: increased the participant's knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of stroke, increased knowledge of the acute management of stroke and that stroke should be treated as a medical emergency.

Four open-ended questions asked participants if there were any topics in relation to acute stroke management that they did not feel had been covered or that they did not find useful. Participants were also asked to identify the most useful features of the course. Finally, participants were asked to suggest changes to the course.

Results

Between February 2006 and July 2009, 1446 emergency health professionals completed the RESPONSE course, 570 (39%) completed the course evaluation and these are the results that will now be presented.

Further information about participants’ job role is available in Table 1. There are twelve ambulance service trusts in England and uptake of the course across these varied significantly (Table 2). Thirty-three (5.6%) participants were from outside England but included Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and abroad. A further seven (1.2%) were from search and rescue services and three (0.5%) from St. John's Ambulance.

The first question within the evaluation was ‘How satisfied were you with the course? 555 (97.3%) participants were either very satisfied or satisfied with the course.

‘I thought the course overall was easy to use, interesting and I felt like I had learned something. Do you have courses that cover any other topics?’

‘It was good to have the opportunity to learn more about acute stroke and the certificate of completion can be used towards my continuing professional development.’

Fifteen (2.7%) participants were not satisfied with the course, mainly due to technical problems and not being able to download the course content.

Completion of the course was assessed with a twenty question multi-choice test, 547 (95.7%) were also either very satisfied or satisfied with the multi-choice test as the method of assessment.

‘I enjoyed the multiple-choice test, it was interesting to see how I scored!’

‘Getting your score straight away on the multi-choice was a bonus, you don’t have to wait for your results and you can see what questions you got wrong.’

‘I passed the multiple-choice test and received my certificate for completing the course. This will go into my continuing professional development folder.’

Twenty-three (4.3%) were not satisfied with the method of assessment. Reasons for this included a dislike of multiple-choice tests, ambiguous questions and a need for further learning resources.

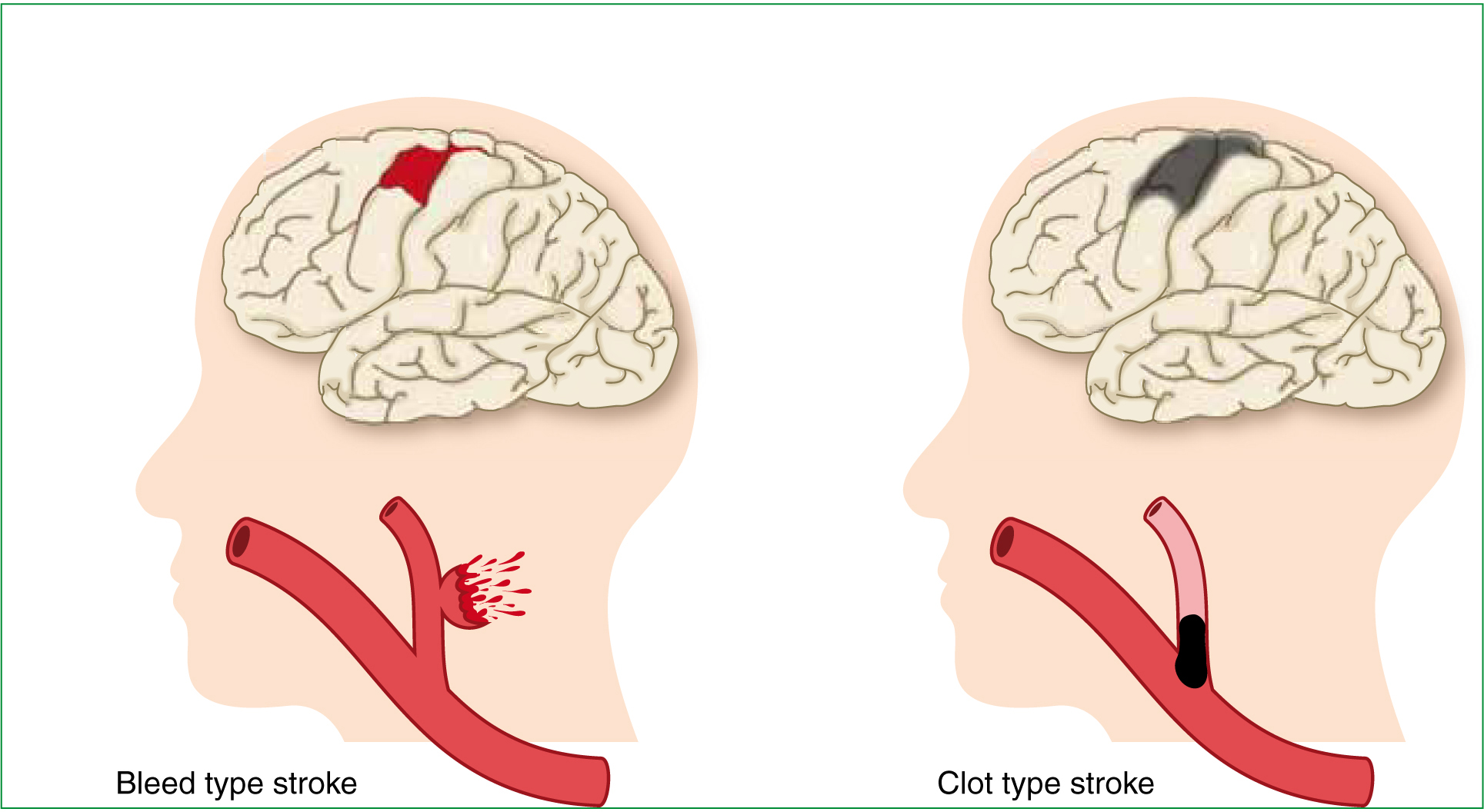

The course contains interactive animations which demonstrate the relationship between the cerebral arteries affected by stroke and the physical symptoms that patients present with. Within the animations, physiological parameters can be altered, enabling the student to see the effects on the post-stroke brain. The animations were found to be one of the best features of the course and 495 (86.6%) of participants were either very satisfied or satisfied with the content and usability of the animations.

‘The animations were particularly good as it made you realize the importance of oxygen saturation that you do not always think about when reading a text book.’

‘The animations were very helpful in visualising the damage that occurs in someone's brain.’

541 (94.7%) were either very satisfied or satisfied with the usability of the course.

‘The ease of online learning was very good. A pleasant experience.’

‘The ease at which I could work through the course at my own pace.’

Twenty-nine (5.3%) participants were unable to access the animations for technical reasons, often as a result of different web browser settings on ambulance trust computers that could only be adjusted by senior managers.

As the course was aimed at all ambulance personnel, the level of the course may have been an issue as the course has been completed by a range of ambulance and emergency from students and trainees to managers and clinical leads. 544 (95.2%) were either very satisfied or satisfied with the level of the course.

‘I was pleased that the course was not set at too high a level. I have come away feeling that I have learnt a lot without being overwhelmed with facts.’

‘I found that the module was pitched at exactly the right level. The more complicated areas were explained clearly and the whole layout of the subject matter was excellent.’

During the development of the course, it was decided by the project steering group that the course content should include information that may be of interest to ambulance staff but may have been more in-depth than required by some participants.

546 (95.6%) reported an increased knowledge in the management of acute stroke and 550 (96.3%) reported an increase in their awareness of stroke as a medical emergency. Twenty-four (4.4%) participants did not report an increase in knowledge and twenty (3.7%) did not report an increase in awareness of stroke as a medical emergency. These participants reported that their previous levels of acute stroke knowledge exceeded the information contained within the course materials. The best features of the course were found to be the presentation of the course content and the animations.

Presentation of the course content

‘The user friendly way in which the content was broken down into smaller sections. Also there was not too much information given on any one page to overwhelm the reader.’

‘Short, sharp, clear and concise slides. Not confusing or overloaded with too much additional information.’

‘The fact that the information was explained simply and without too much medical jargon really helped me to follow the content a lot better.’

Animations

‘The animations assisted in the understanding of anatomy and physiology involved.’

‘The animations helped me to visualise what goes on inside someone's brain when they have a stroke.’

‘It was interesting to see what happened to the brain when oxygen levels were altered.’

Specific aspects of the course content

‘The range of information, especially about different types of stroke and how they present in patients’

‘The different types of stroke and stroke mimics.’

‘The references provided some valuable research material.’

‘The management section is very helpful as we do not get enough training on this. I didn’t realise how important patient positioning is in a stroke patient.’

Within the evaluation, all participants were asked to suggest areas of information that they felt should be included but were not. We also asked participants to identify areas of the course that needed to be improved. Some participants had difficulty in using the animations. This was mainly due to the configuration of computers or older computers that resulted in delays when loading the animations.

‘Advise students that the animations do not display properly in some Internet browsers, they worked fine though when I used Internet Explorer.’

‘Loading the animations took too long, I don’t know if this was a problem with the course or my computer. Some guidelines on this may be useful.’

Students are given a two week time limit in which to access and complete the course. This time limit can be extended on request however, some students felt that a longer period of access would be more appropriate.

‘I would have liked longer access to the course based on the demands of work and limited access to a computer.’

‘With shift patterns, work and other commitments, access to the course for longer would have been useful.’

‘I asked for an extension to the course which was fine but maybe more time could be granted to access the course initially.’

Discussion

The positive aspects of this web-based course have been identified as its usability, interactive nature, and flexibility. This online acute stroke course has also been shown to increase knowledge among emergency health professionals and provides a flexible approach to learning.

Although the evaluation was only completed by 571 (39%) of participants, this response rate is higher than those reported for online questionnaires, who commonly report response rates of 10% or lower (Witmer et al. 1999).

Although the evaluation was completed by a much smaller number of participants than those who undertook the course, previous research has suggested that the responses from those who do or do not complete evaluations does not differ (Witmer et al. 1999). However, alternative methods of evaluation or follow up of the evaluation, to ensure completion may be required.

Within the twelve ambulance service trusts in the UK, uptake of the course varied significantly. One trust is not represented at all in the evaluations and only three had more than fifty participants.

It is unknown, at this time, why uptake of the course within some ambulance trusts was poor. However, in the future, better uptake could potentially be facilitated by more direct input with training managers and stroke leads.

Within the evaluation, no suggestions or comments were made specifically about the evaluation questionnaire. Although a large proportion of participants did not complete the evaluation, there were not the resources to follow up people by email or other means.

A large proportion of participants reported an increased knowledge in the management of acute stroke and stroke as a medical emergency (95.6% and 96.3%, respectively). However, we did not test knowledge before the course was completed and so this is a subjective measurement.

In healthcare, there have been recent advances towards the use of technology as a tool for facilitating student learning, particularly for those accessing courses from the practice setting (Blake, 2009). There is also a demand for continuing professional development and updating of knowledge and skills (Blake, 2009).

Although the uptake of the course has been encouraging, e-learning is an approach that does not suit everybody's learning style or technological abilities. Other barriers to the use of e-learning may also include a lack of personal discipline (Blake, 2009) and out-of-date computer equipment that may not facilitate elements of an e-learning course such as the use of interactive animations.

As in previous studies (Dames and Handscombe, 2002), this evaluation has highlighted a demand for e-learning resources from both the UK and abroad. The course takes only two hours to complete and is free to access, both features known to facilitate the uptake of e-learning opportunities (Dames and Handscombe, 2002).

Conclusion

As a result of the evaluation, a number of recommendations have been made. The project team will work to identify training leads in trusts where uptake was poor. It is hoped that they will facilitate completion of the course by staff in these areas. A further recommendation is that technical support should be available to participants who may experience difficulties in accessing the course or its content.

Due to the positive feedback about the contribution of this course towards continuing professional development, additional courses and training resources will be made available in the future.