In August 2019, there were 28 308 registered paramedics in the UK (Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), 2019). Retaining these professionals is an increasingly significant problem, with attrition rates rising rapidly (National Health Executive, 2015; Iliffe and Manthorpe, 2019). The broad skillset of paramedics means that those who are not satisfied with their employment are increasingly finding their professional contribution is in demand in other healthcare sectors. Indeed, Egan (2017) reports that fewer than 80% of registered paramedics are employed by NHS ambulance services.

Retention, attrition and associated concepts are complex, with many factors contributing to sickness and staff motivation. For example, the ambulance service is experiencing rising public demand: the National Audit Office (2017) reports a 5.2% increase in annual call-outs recorded since 2012, with ambulance services receiving 11.7 million 999 calls between April 2018 and March 2019 (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2019). This results in growing workloads and has a negative impact on meeting response targets.

A study of 1332 ambulance workers found causes of stress to be tight targets, long hours and physical demands (Unison, 2014). Similarly, Egan (2017) cited constant demands, lengthy and extended shifts, bullying or harassment, and a lack of development opportunities as factors responsible for staff decisions to leave the ambulance service.

A report by Mind (2016) has indicated that 91% of ambulance personnel have experienced low mood or poor mental health while working for the ambulance service. Stress and anxiety are the greatest cause for sickness absence across all staff groups in the NHS at 25.3% but attributed as the reason for absence in 28% of ambulance workers (NHS Digital, 2019). Ambulance staff have also been found to have the highest sickness absences of all NHS staff groups (NHS Digital, 2020).

Despite stress-related illness being a major reason for absence in the ambulance service, there is a paucity of research in this area (Hegg-Deloye et al, 2014). The research available shows paramedics are more likely to experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than other emergency service workers, and this can have a profoundly detrimental impact on personal and professional life (Drewitz-Chesney, 2012).

Much of the research around paramedics and PTSD argues that it is not always caused by major incidents but can arise from ‘smaller everyday events’ that trigger illness or symptoms (Lateef, 2005). Donnelly (2012) concurs, highlighting that ‘normal’ stress was shown to be damaging to staff wellbeing. However, 52% of clinicians have indicated that traumatic events trigger stress responses but other factors, such as an excessive workload (68%), pressure from management (60%) and changing shift patterns (56%), were rated much higher and left staff feeling fatigued and exhausted (Mind, 2016).

Fatigue is associated with burnout, sick leave, attrition, work disability, impaired performance and reduced physical and mental health (Courtney et al, 2013). Stress and fatigue have significant negative impacts on clinical performance, including increased incidents of drug and documentation errors (Leblanc et al, 2012). The Larrey Society (2015) identified managing injury, violence and death as the main contributors to stress in ambulance staff. However, there is a paucity of high-quality research explaining why staff are stressed (Mildenhall, 2012).

In recent years, investigations have begun into the concept of occupational burnout as a leading cause of poor employee mental health. In particular, this has been noted as contributing to absenteeism and poor staff retention in the ‘helping professions’ (Adams et al, 2017; Zeng et al, 2020). Burnout has frequently been reported at higher levels in the emergency services when compared with other helping professions (Adams et al, 2017; Thyer et al, 2018). According to Mind (2021), ambulance service staff reported poorer mental health than police and fire employees. Ambulance staff were also the most likely to say their mental health had deteriorated since the pandemic.

Burnout is a term that encompasses many negative effects of stress and is defined as a psychological syndrome involving burnout (emotional exhaustion), depersonalisation (cynicism) and a diminished sense of achievement (Maslach, 1982). Burnout is the term used to describe exhaustion and involves fatigue, trouble sleeping and physical problems that are caused by work alone. Depersonalisation refers to cynicism with a reduction in empathy and excessive detachment towards patients and colleagues. Low personal achievement concerns a sense of inefficacy and measuring the extent to which participants assess themselves negatively and feel their efforts bring about no positive change; this is seen as a consequence of burnout and depersonalisation (Maslach et al, 1997).

Methodology and design

A two-phase survey was designed explicitly to address the research aims (Cresswell, 2013). The validated Maslach Burnout Inventory and the Copenhagen self-assessment burnout tools informed part 1 (Maslach et al, 1997; Kirstensen et al, 2005; Molinero Ruiz et al, 2013). Part 2 of the survey used qualitative open questions informed by the literature review.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory was used in its entirety; questions from the Copenhagen burnout tool were selected according to their relevance to the literature review with respect to topics such as fatigue, work-life balance and the causes of stress. The questionnaire was piloted with a test group of 11, and changes suggested by pilot participants were discussed with the authors. Statistician input was received to inform the questionnaire design to ensure an effective data analysis strategy.

The study setting was a large ambulance trust in the north of England. Ethical approval and permission were gained from the trust and the authors' university. The electronic questionnaire was distributed to all frontline staff of any grade working on emergency response vehicles.

Nominal data were collected directly from SmartSurvey and exported into Microsoft Excel to retrieve quantitative information for descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. Data were collected using the Maslach burnout self-test scale (Maslach et al, 1997). Quantitative data were analysed as a whole and across demographic groups. Qualitative data involved phased coding, and a coding frame based upon key themes developed and displayed below.

Findings

Demographics

In total, 495 staff responded to the survey and 382 fully completed questionnaires were included in the analysis.

Table 1 presents the overall demographics of the 382 participants and data from part 1. Clinicians are defined as those in a qualified role such as paramedics (including those with specialisations), emergency care practitioners and qualified emergency medical technicians. Non-clinicians are those who are in assistant practitioner, emergency care assistant and emergency medical technician 1 roles, who are in a double-crewed ambulance and support the clinician as their crewmate.

| Demographic | Burnout | Depersonalisation | Personal achievement | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total respondents | % of total | High | Mod | Low | High | Mod | Low | High | Mod | Low | |

| All staff | 382 | 100% | 15% | 38% | 47% | 67% | 20% | 13% | 94% | 5% | 1% |

| Role | |||||||||||

| Non-clinicians | 80 | 21% | 10% | 46% | 44% | 55% | 21% | 24% | 93% | 3% | 4% |

| Clinicians | 302 | 79% | 17% | 36% | 47% | 71% | 20% | 9% | 95% | 0% | 5% |

| Sex | |||||||||||

| Female | 157 | 41% | 13% | 53% | 34% | 70% | 22% | 8% | 96% | 3% | 1% |

| Male | 225 | 59% | 17% | 42% | 41% | 65% | 19% | 16% | 93% | 6% | 1% |

| Age | |||||||||||

| 18-24 | 14 | 4% | 0% | 57% | 43% | 43% | 43% | 14% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| 25-34 | 90 | 24% | 9% | 42% | 49% | 56% | 27% | 17% | 98% | 2% | 0% |

| 35-44 | 135 | 35% | 15% | 50% | 35% | 73% | 17% | 10% | 90% | 9% | 1% |

| 45-54 | 119 | 31% | 24% | 45% | 31% | 74% | 17% | 9% | 97% | 2% | 1% |

| 55+ | 24 | 6% | 8% | 50% | 42% | 63% | 17% | 20% | 88% | 8% | 4% |

| Time in role | |||||||||||

| <5 years | 87 | 29% | 5% | 40% | 55% | 47% | 31% | 22% | 86% | 11% | 3% |

| 6–10 years | 99 | 26% | 18% | 48% | 34% | 70% | 22% | 8% | 96% | 4% | 0% |

| 11–15 years | 73 | 19% | 15% | 53% | 32% | 84% | 12% | 4% | 96% | 3% | 1% |

| 16–20 years | 56 | 15% | 23% | 56% | 21% | 82% | 11% | 7% | 98% | 2% | 0% |

| 21–30 years | 32 | 8% | 28% | 47% | 25% | 72% | 16% | 13% | 100% | 0% | 0% |

| ≥31 years | 12 | 3% | 33% | 25% | 42% | 75% | 25% | 0% | 92% | 8% | 0% |

| Place of work | |||||||||||

| Ambulance | 286 | 75% | 13% | 38% | 49% | 66% | 20% | 14% | 95% | 4% | 1% |

| Rapid response vehicle | 96 | 25% | 21% | 39% | 40% | 72% | 20% | 8% | 93% | 7% | 0% |

Mod: moderate

Participant demographics were compared with those of the overall trust workforce. The sample group were broadly comparative to the organisational population, although non-clinicians were slightly under-represented.

Place of work relates to the vehicle on which the respondent attends 999 calls for the majority of their shifts; this is either the rapid response vehicle or the double-crewed ambulance.

Part 1. Quantitative findings

Three categories of questioning covered burnout, depersonalisation and personal achievement.

Burnout

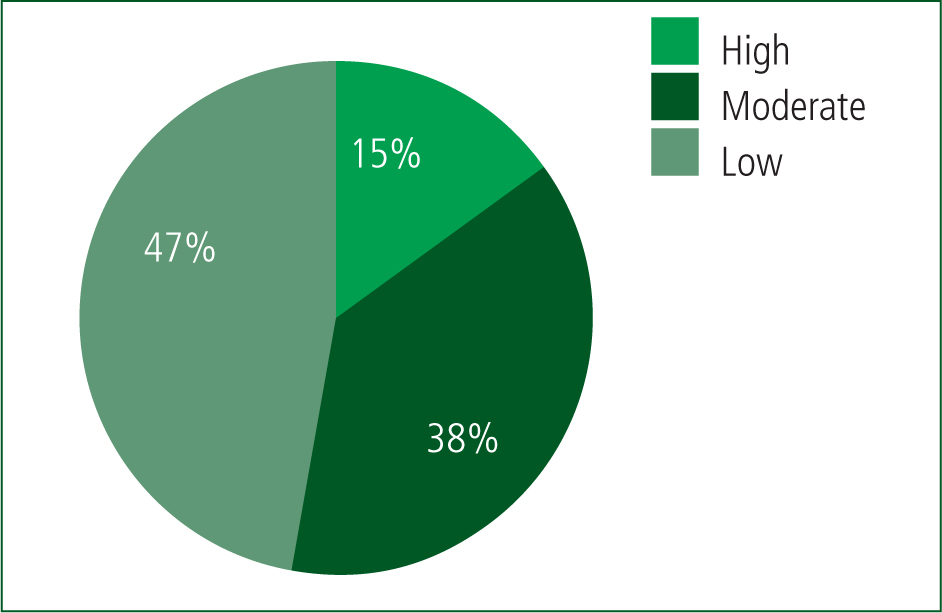

Of the 382 respondents, 47% (n=180) showed a low risk of burnout but, more concerningly, 15% (n=57) showed high levels of burnout and more than 38% (n=145) had moderate burnout (Figure 1). This translates to more than 50% of ambulance staff surveyed demonstrating symptoms of burnout including exhaustion and fatigue.

Depersonalisation

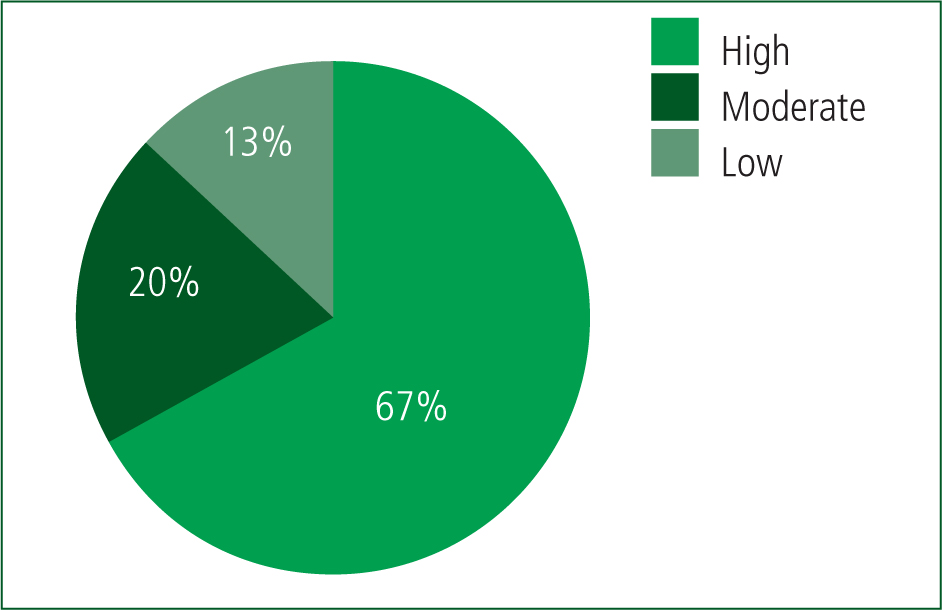

High levels of depersonalisation were found in 67% (n=256) of respondents. Moderate levels occurred in 20%, indicating that almost 90% of ambulance staff were displaying depersonalisation, i.e. cynicism, detachment and reduced levels of empathy and while at work (Figure 2).

The results as a whole show that burnout is associated with depersonalisation but not with personal achievement. Depersonalisation and burnout were then considered by comparing each individual's responses for both data sets. A Pearson correlation coefficient was used to analyse the data, and the coefficient was found to be 0.6026. This indicates that someone who feels burnout is likely to also feel depersonalised to an equal or greater level.

Personal achievement

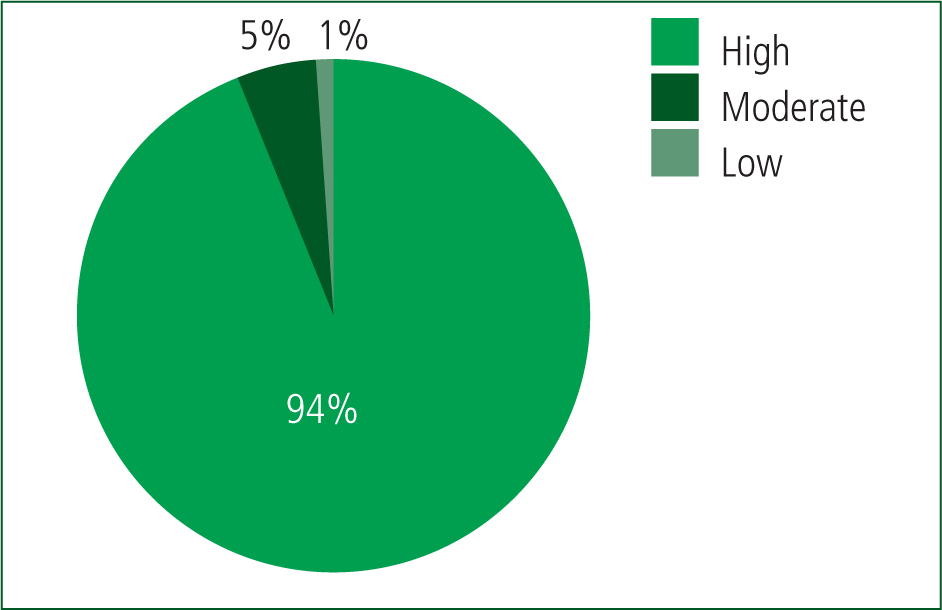

There were high levels of burnout and depersonalisation. However, despite this, 94% (n=359) of respondents showed high levels of personal achievement, with only 10% demonstrating low levels (Figure 3). These results clearly show that a significant majority of the participants felt they could still achieve positive change in their daily work. The 10% (n=38) of respondents showing low levels of personal achievement also had high levels of burnout and depersonalisation.

Key findings from demographics

Overall, key demographic findings were:

Part 2. Qualitative findings

Job enjoyment and satisfaction

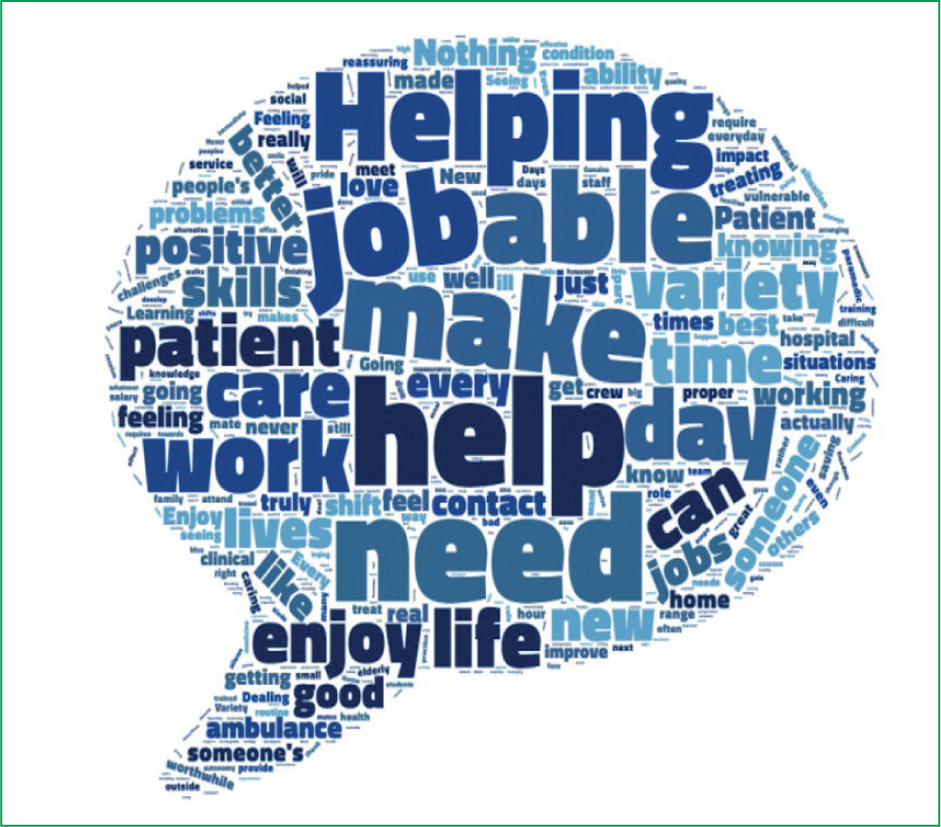

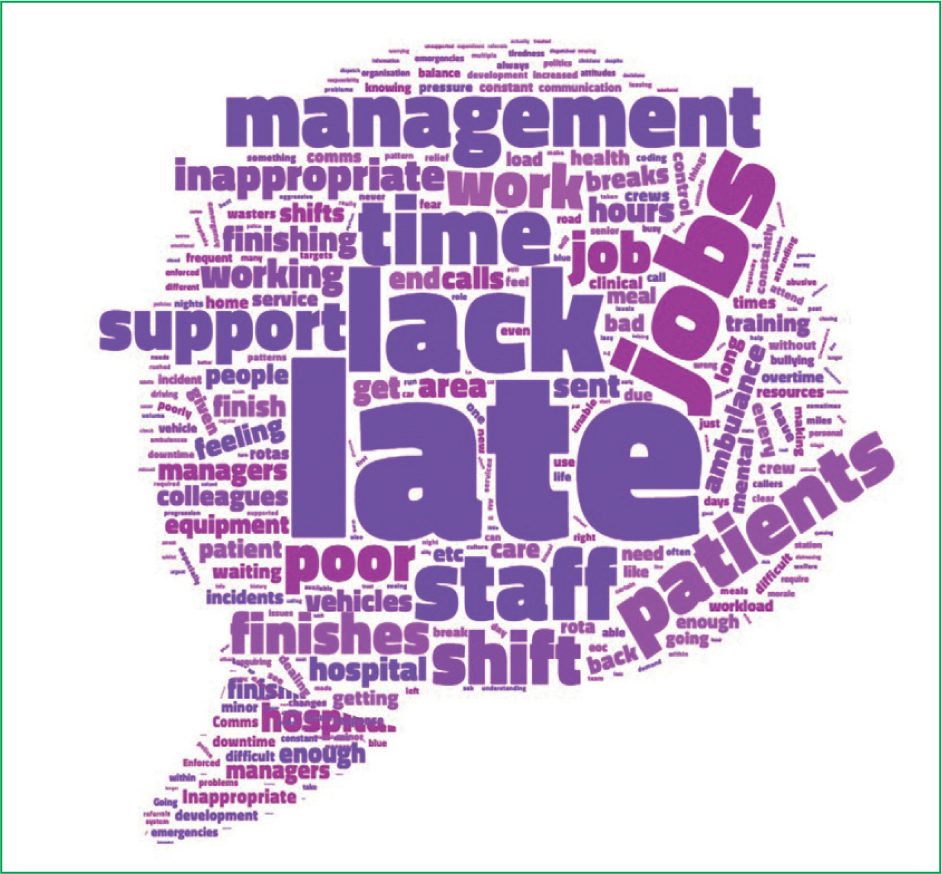

The data gained were transferred to word frequency graphs then copied into a word cloud programme to create a visual representation of the frequency of words used in comments (Figures 4and5).

One of the key themes to emerge was that ambulance staff clearly enjoy helping people and feel they pursued a career in the ambulance service to make a positive impact. ‘Making a difference’ seems to be one of the most rewarding aspects of the job and this phrase was used by 24% of respondents. This is a recurrent theme in the qualitative feedback. Indeed, job satisfaction appears to be highest when a participant's positive expectations of the role are fulfilled.

Many participants placed a great deal of value in the caring and supporting aspects of their role.

Clinical variation was recurrently cited as a reason why staff enjoyed their job. Many participants referred to ‘proper jobs’—i.e. jobs where their clinical skills and training could be used. This reflects a common frustration that a lot of time and energy is spent responding to non-emergencies.

Understanding the aspects of the job that people value and enjoy the most is key to discovering their motivation to join and remain working for the ambulance service. Similarly, the pain points and problems that cause stress and demoralise staff working on the frontline need to be identified.

Frustrations

Many of the frustrations raised in the qualitative feedback stemmed from shift planning, meal breaks and finishing shifts on time. The present study showed that some ambulance service staff felt they were thought of as ‘dots on a screen’ rather than people.

Finishing work late was highlighted as a problem by 34% of staff in the qualitative feedback, who felt it was a daily occurrence. When combined with a lack of proper meal breaks or rest periods between jobs (mentioned by 22% of respondents), late finishes contributed to feelings of depersonalisation and further alienated those who felt a work-life balance was not being achieved.

A high workload was also referred to by 27% of the participants; staff felt they were unable to spend time reflecting with colleagues, had no ‘down time’ or time to keep up to date with training. A perceived lack of support from managers and respondents feeling that misuse of the emergency services by the general public was apparent if they were not required to administer any medical interventions. Inappropriate coding of jobs was highlighted as frustrating to 24% of ambulance staff, causing unnecessary delays to seriously ill patients, ambulances being sent to patients by other health professionals where staff felt they did not require emergency medical help, and abuse from the general public. This was related to the finding that 23% of staff believed they were unsupported or put in danger on a regular basis.

Another source of frustration that came through in the qualitative data surrounded triaging by 111 services and dispatchers/communications. A major disconnect between NHS trust management and frontline staff was highlighted by 52% of respondents; specifically, there was a perceived lack of support or pastoral care. Feeling undervalued and a lack of positive feedback were among the main reasons cited for management-related stress.

Recommendations

Staff wanted to feel valued and receive positive praise, which they felt was lacking. Proactive health screening for physical and mental problems was suggested.

The word ‘late’ was mentioned 131 times (34%) and related to finishing work late on a regular basis. Work-life balance was also discussed, where staff felt improved, flexible rotas, along with being able to finish their shifts on time would have a positive influence on this.

Participants also wanted time to complete continuing professional development (CPD) while at work, with a clearer career framework for progression in place. Training and development was cited (n=30; 8%) as something staff would like to receive more frequently.

Some of the suggestions around how morale could be improved would be fairly simple and straightforward to implement. This research seems to suggest that small gestures could go a long way to improving wellbeing.

Discussion

Burnout and its causes are complex and a significant problem for ambulance services across the globe. The results of this study go some way to understanding the concept further.

The results found that more than 50% of the staff were experiencing signs of burnout; concerningly, 15% of these individuals reported they were experiencing high levels of burnout in connection with work. Moderate levels of burnout have not been distinctly defined; however, it would be reasonable to conclude that these staff have some of the symptoms of burnout and are negatively affected by work.

Staff experiencing burnout are not simply exhausted or overwhelmed by their workload but have lost their psychological connection, which has implications for their motivation and their identity, as well as service delivery as a whole (Leiter and Maslach, 2016).

A positive relationship was found between burnout and depersonalisation; staff who displayed high levels in one were more likely to show high levels in the other. The results revealed high levels of depersonalisation were much more common than high levels of burnout. High levels of depersonalisation were found in almost 70% of staff, and high or moderate levels in almost 90%, indicating a strong level of cynicism. This can have a negative impact on staff morale and service delivery as it can cause staff to connect negatively in patient care (Leiter and Maslach, 2016).

Reassuringly, personal achievement was high, with 94% of all respondents reporting high levels. It would therefore appear that ambulance staff, despite feeling burnout, can still have a high sense of efficacy.

Those at risk of burnout tend to show high scores for burnout and depersonalisation and low scores for personal achievement (Maslach et al, 1997). This was not the case for the majority of respondents in this study as only 38 scored low; however, these individuals scored highly for burnout and depersonalisation. Therefore, 38 respondents (10%) showed scores suggesting they may be particularly at risk of exhaustion, cynicism and inefficacy. Clinicians, men, those aged >35 years, people who had been in the same role for >6 years and staff working in the rapid response vehicle were found to be most at risk from burnout.

The high levels of personal achievement indicate that the participants in this study appeared to enjoy their jobs and thrived when helping others. A major frustration, however, was finishing late on a regular basis and resources not being used effectively, with a perception that the ambulance service was being misused.

Participants also wanted better resources and staffing levels. The current workload appeared to be overwhelming and negatively affected their mental health and work-life balance.

People also wanted a clear career pathway to follow and more training to aid career progression. Indeed, participants suggested they would benefit from more time with their clinical supervisors and regular training opportunities. Interdisciplinary support and professional education have been suggested as mechanisms for recruiting and retaining paramedics (Mulholland et al, 2009; The Larrey Society, 2015).

Intense and busy workloads, as well as rising staff exhaustion, result in few opportunities for discussion and reflection between calls, which are important to processing traumatic events. Debriefing is beneficial and can occur only in downtime, with time to allow reflection following difficult calls (Quaile, 2016).

Consideration of more person-centred shift patterns may also have a positive effect on staff. Overwhelmingly, participants struggled with feeling disengaged from management, not feeling valued and wanting more positive feedback and support. Regehr and Millar (2007) recommend reducing organisational stressors, which can be achieved by increasing support for staff and providing a sense that their skills and contribution are valued.

Considering the potential impact that burnout can have on ambulance service productivity and staff retention, the recommendations below for improved support may help to reduce these negative effects; addressing work-life balances and burnout of ambulance crews should be a priority (The Larrey Society, 2015).

To effectively support staff, there is a need to reduce the stigma around mental health problems. Mind (2016) found that 80% of ambulance staff thought that their employer did not encourage them to talk about mental health, suggesting a huge barrier in talking about this problem.

Respondents also appeared concerned about their physical health and felt it was deteriorating because of work demands. Promotion of wellbeing can improve commitment, job satisfaction and staff retention (Health and Safety Executive, 2008).

Limitations

This study was undertaken in one large ambulance trust but may not represent the workforce as a whole. However, many of the findings and themes will be transferable to other ambulance staff.

This study relied exclusively on participants self-reporting their own levels of burnout, which could raise issues of measurement error (Sharma and Cooper, 2017).

This research was conducted before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic so does not take into account the added pressures of frontline work during a health crisis.

Conclusion

Ambulance staff are passionate about their role. However, burnout is a significant and very real issue that decreases staff efficacy and reduces quality of patient care. Ambulance services need to address this issue.

Certain staff groups appear more vulnerable to burnout: male clinicians, lone responders, those aged >34 years and people who have been in the same job for >6 years.

Support from senior management needs to be increasingly apparent, including communication and efforts to improve employees' sense of wellbeing.

Further research is needed to gain more insight into this problem and create more effective solutions to combat burnout.