Occupational stress is a significant health issue affecting UK ambulance workers and a central theme identified in the Employee Mental Health Strategy from the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE) (2018). By its very nature, the paramedic role lends itself to an unscheduled and often chaotic environment where individuals are expected to make rapid clinical decisions in the face of increasing public scrutiny (Mildenhall, 2012).

According to the Health and Safety Executive (2010), occupational stress concerns the adverse or detrimental reactions that staff experience in response to disproportionate levels of pressure placed upon them at work. In prehospital care, exposure to traumatic events, driving at speed and working long or unsociable hours significantly increase the risk of burnout, leading to reduced job satisfaction, increased absenteeism and a diminished quality of care (Thyer et al, 2018). With 91% of ambulance staff having experienced stress, low mood or anxiety related to their working environment, sickness rates among ambulance services now exceed those of all other NHS organisations (NHS Digital, 2017). A greater emphasis should be placed on developing health and wellbeing models to support the holistic welfare of staff.

Mindfulness, put simply, is a form of meditative practice defined by an ability to foster clear thinking and open-heartedness through the psychological quality of bringing one's complete attention to the experience of the present moment in a non-judgmental way (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Requiring no specific cultural or belief system, the practice is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2009) because it has an array of positive effects on human functioning including relaxing the body and calming the mind.

In the first government initiative of its kind globally, the UK Mindfulness All Party Parliamentary Group (MAPPG) (2015) commissioned a year-long inquiry report analysing the evidence associated with mindfulness in four areas of national interest: health; education; the workplace; and the criminal justice system. Subsequently, the MAPPG endorsed the concept as a preventive and cost-effective method of tackling growing levels of occupational stress within the NHS.

Though the methods for mindfulness training have long been associated with the contemplative traditions of Asia, there has been a rapid increase in academic literature on the subject between 2005 and 2015, with more than 500 peer-reviewed scientific papers being published each year (MAPPG, 2015).

However, despite the recent surge in research, limited evidence exists to inform the potential benefits of mindfulness in prehospital care. This study sets out to explore whether mindfulness activity can improve the occupational health of paramedic clinicians.

Literature review

Evidence supporting the effectiveness of mindfulness for health professionals is broad and covers a variety of clinical domains including nursing (Kang et al, 2009; Foureur et al, 2013; Zeller and Levin, 2013; Botha et al, 2015; dos Santos et al, 2016; Van der Riet, 2018), general practice (Hamilton-West et al, 2018) and primary care (Fortney et al, 2013).

The most robust evidence comes from a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Goyal et al, 2014; Burton et al, 2016; Lomas et al, 2018), in which the authors equally conclude that mindfulness has the potential to lower levels of stress and neuroticism, while improving both wellbeing and job performance in healthcare workers.

With more than 20 published studies investigating alterations in brain morphometry related to mindfulness practice, the literature shows the emergence of a stream of research developments in neuroscientific exploration (Fox et al, 2014; Tang et al, 2015).

A study by Brefczynski-Lewis et al (2007) established that mindfulness activity was associated with activation in multiple brain regions implicated in monitoring (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), engaging attention (visual cortex) and attentional orienting (superior frontal sulcus, supplementary motor area and intraparietal sulcus).

A review on the effects of mindfulness meditation by Ngô (2013) found that regular practice seemed to improve immune function, diminish the reactivity of the autonomic nervous system, increase telomerase activity and lead to higher levels of plasmatic melatonin and serotonin. Although there are questions over the methodological validity of many mindfulness studies, the body of literature provides consistent parallels between the cultivation of more mindful ways of being and a tendency to experience less emotional and psychological distress (Greeson, 2009).

Aims and objectives

The aims and objectives of this study were to:

Methods

Since the philosophical roots of pragmatism endorse strong and practical empiricism as the path to determine efficacy, a mixed-methods approach was used. The justification of using this design was linked to an ability to draw strengths, while minimising the weaknesses of both methods within a single study (Johnson, 2007).

Phase 1 of the study involved drawing up and distributing an anonymous email survey using the online survey administrator, AllCounted. This was sent to 300 paramedics across an unnamed NHS ambulance trust in the UK. The survey asked participants to identify the extent to which seven work-related factors affected their occupational health levels, as well as to answer questions to establish their knowledge and experience of trust health and wellbeing policy and mindfulness practice. Included was a participant information sheet, which described the study's purpose and successful completion was taken as a means of establishing implied consent.

Phase 2 centred on the delivery of a structured 30-day mindfulness activity programme using NHS-approved interactive mindfulness application, Headspace. Participants were encouraged to undertake 10 minutes of guided mindfulness activity daily and record their views. A purposeful sample was taken from five participants who had highlighted an interest in progressing from phase 1. This strategy made effective use of limited resources and was further reinforced by factors related to participant willingness and availability.

An introductory workshop was held to familiarise participants with the mindfulness concept and a focus group was undertaken as a method of establishing research credibility via the qualitative process of member checking (Guba and Lincoln, 1981).

Formal ethical approval for the study was gained from the trust research development team, as well as the ethics committee of Liverpool John Moores University. A commitment to responsible data collection strategies ensured that the themes of beneficence, non-maleficence and respect were observed. All data were collected during September 2018 and stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act (1998) and the General Data Protection Regulation.

Data analysis

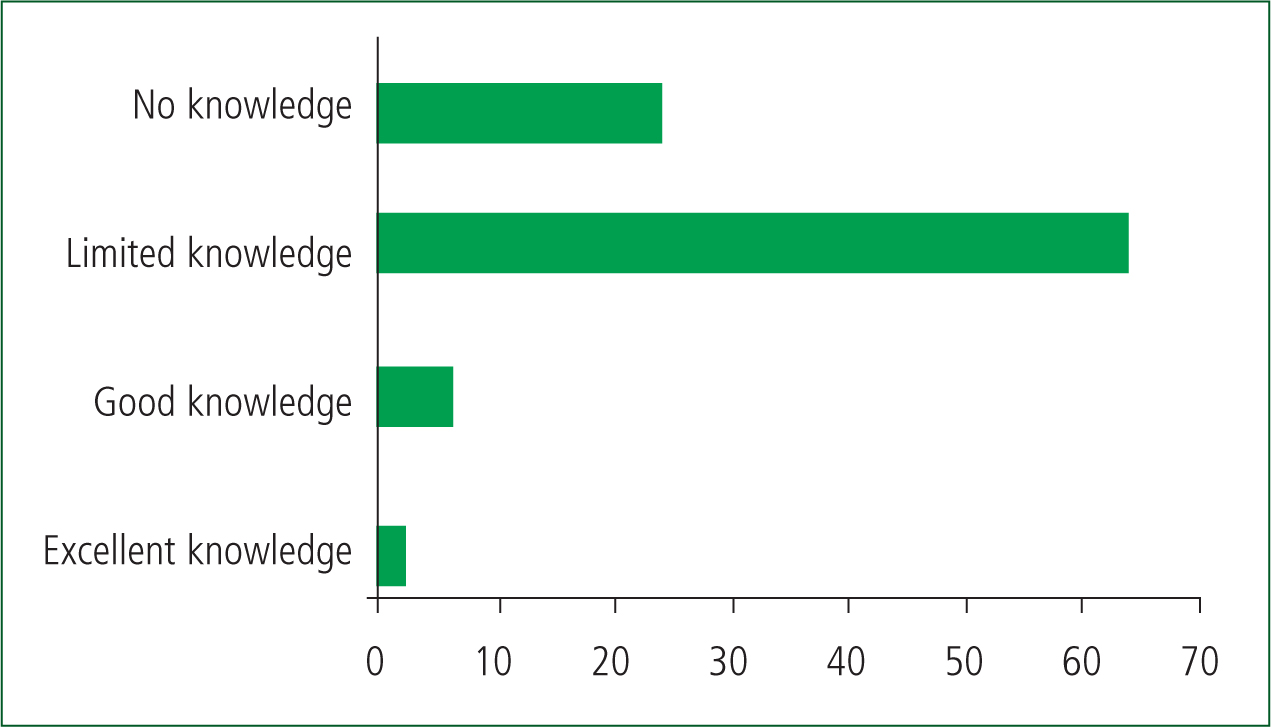

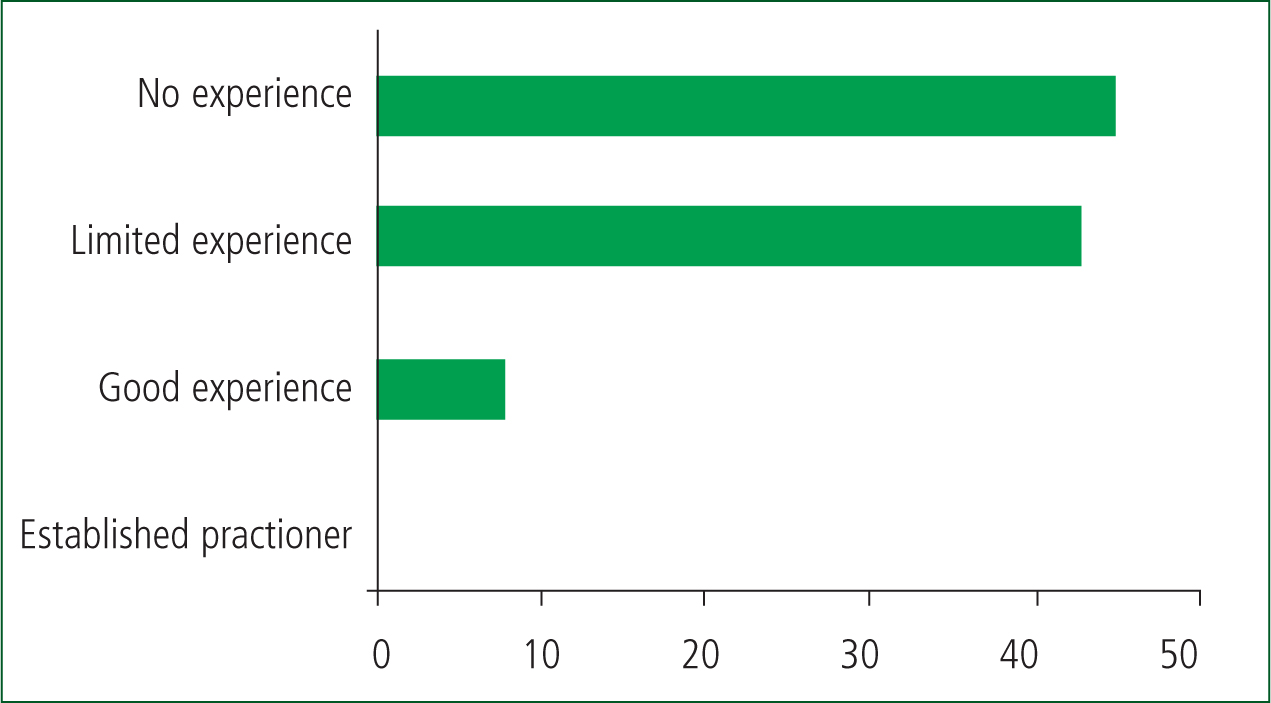

Survey information from phase 1 was analysed using the statistical analysis tool in AllCounted. The seven occupational health factors were quantified using an impact severity scale (Table 1). Knowledge and experience of trust health and wellbeing policy and mindfulness practice were further quantified via a Likert-style scale of values that ranged from no knowledge/experience to excellent knowledge/experience (Figures 1 and 2).

| Impact severity | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Role unpredictability | None | 33 | 34.7% |

| Moderate | 45 | 47.3% | |

| Considerable | 13 | 13.2% | |

| Significant | 4 | 4.2% | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.9% | |

| Shift working | None | 2 | 2.0% |

| Moderate | 34 | 35.4% | |

| Considerable | 36 | 37.5% | |

| Significant | 24 | 25.0% | |

| Blue light driving | None | 36 | 37.8% |

| Moderate | 40 | 42.1% | |

| Considerable | 16 | 16.8% | |

| Significant | 3 | 3.1% | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.9% | |

| Demands of emergency work | None | 6 | 6.2% |

| Moderate | 48 | 50% | |

| Considerable | 32 | 33.3% | |

| Significant | 10 | 10.4% | |

| Work/life balance | None | 9 | 9.6% |

| Moderate | 31 | 33.3% | |

| Considerable | 46 | 49.4% | |

| Significant | 7 | 7.5% | |

| Missing | 3 | 2.3% | |

| Work-related rumination | None | 2 | 2.0% |

| Moderate | 60 | 62.5% | |

| Considerable | 31 | 32.2% | |

| Significant | 3 | 3.1% | |

| Political/trust Issues | None | 8 | 8.6% |

| Moderate | 43 | 46.7% | |

| Considerable | 32 | 34.7% | |

| Significant | 9 | 9.7% | |

| Missing | 4 | 3.6% |

Participant experiences in phase 2 were recorded using a voice-to-text dictation application and sent to the researcher at 10-day intervals for thematic investigation using qualitative data analysis tool, NVivo 12. To ensure anonymity, the names of participants were replaced with identification codes.

Results

In all, 96 responses were received within phase 1, with an overall survey return rate of 32%. Of the factors affecting occupational health, ‘moderate impact’ was the commonest response by participants in the five areas of role unpredictability (n=45; 47%), blue light driving (n=40; 42%), workplace demands (n=48; 50%), rumination (n=60; 62%) and political/trust issues (n=43; 47%). A ‘considerable impact’ was the dominant factor in the remaining two areas of shift working (n=36; 37%) and work/life balance (n=46; 62%). Quantitative significance in relation to both health and wellbeing policy and mindfulness activity identified that participants had either no knowledge (n=24; 25%) or limited knowledge (n=64; 66%) of health and wellbeing policy, coupled with no experience (n=45; 47%) or limited experience (n=43; 48%) of mindfulness activity. When asked if they would consider taking part in the practical phase of the study, 66% (n=63) of respondents indicated they were willing.

Of the five participants within phase 2, four completed all elements of the 30-day mindfulness schedule; one completed 26 daily sessions but did engage fully with the researcher throughout. All participant transcripts were documented verbatim and analysis of the combined records produced three prominent themes.

Theme 1. Psychological robustness

Though individual accounts varied, a general agreement was established among participants that daily exposure to mindfulness practice strengthened a sense of metacognitive awareness and supported a heightened amount of emotional stability in relation to the various stressors experienced at work.

Describing how the sessions provided them with a psychological platform to better contextualise their understanding of thought process, participants emphasised greater degrees of self-efficacy, composure and associated cognitive flexibility:

‘There is no doubt that paramedic work can put you in an emotionally vulnerable state; there are so many things that can knock you off balance. For me, cultivating mindfulness has given me a new perspective in that I feel stress is not necessarily something that happens to you but is rather a consequence of your reaction to what happens.’ (Participant 3)

Similarly, clinicians reported how gaining a gentle appreciation for the meditative process of simply observing thoughts without judging, labelling or becoming attached to them meant that they were more likely to recognise and avoid neurotic thought patterns associated with the prehospital environment.

‘No matter how busy we are as a service, we can only deal with one incident at a time. Becoming more aware of my experiences in the present moment has enabled me to focus more on what is happening with my patient in the here and now, rather than worrying about things that I cannot control, like how many jobs are waiting.’ (Participant 2)

Theme 2. Physical resilience

Paramedics described emergency working as emotionally and physically exhausting, which they said contributed to an array of neuroendocrine-related changes in the body, leading to increased levels of fatigue and restlessness, and a heightened risk of musculoskeletal injury.

One account described how the body scan/body awareness meditations, which were recommended following a shift, facilitated an increased sense of physical relaxation by promoting a physiological return to the body's natural homeostatic state.

‘Nights shifts leave me physically exhausted, particularly the dreaded 60-hour block. The release of stress hormones like cortisol during work inhibit my ability to relax following shift. Since adopting the techniques in the Headspace app, I have experienced a noticeable improvement to my sleeping patterns, which I feel has helped a lot.’ (Participant 1)

In addition, paramedics reported how their shifting work/life balance meant that they were less likely to make informed food choices when it came to support their physical health. Describing how mindfulness could help to ensure nutritional requirements were met, one practitioner said their daily practice inspired them to be more conscious about food choices; they said this resulted in their having more sustainable energy levels over the course of a shift, leading to better levels of concentration, memory and overall performance.

‘There's an education to be had when it comes to mindfulness; it can literally be applied to anything. Being more mindful of my eating habits means that I am less likely to act spontaneously when it comes to making food choices at work’. (Participant 5)

Theme 3. Interpersonal relationships

Participants reported low levels of motivation and self-care linked to the excessive demands placed on them at work. This was highlighted as a key factor affecting their ability to form effective working relationships with control staff and managers.

Additionally, participants indicated how the nature of emergency work required a specific, task-focused mindset, which they say led to an amplified sense of psychological depersonalisation with patients and their families. Although widely considered a precursor to the development of post-traumatic stress, most participants described depersonalisation as a protective mechanism against the threat of ruminating thoughts associated with traumatic exposure.

Despite the professed barriers, collective accounts indicated that self-acceptance and compassion-orientated sessions increasingly empowered paramedics to reconnect with both patients and colleagues in more expressive and meaningful ways, resulting in enriched satisfaction with relationships:

‘Behind the facade of the tough guy stereotype, it is important to acknowledge the psychological susceptibility faced by paramedics. Implementing a humanistic approach to mindfulness has enabled me to embrace the principles of compassionate self-care, providing a heightened degree of confidence and gratitude for the privileged position of supporting patients during their time of need.’ (Participant 1)

Focus group

Though participants reported some minor technical complexities related to the voice-to-text dictation application, the group predominantly described a holistic, positive experience of their time spent on the programme, coupled with a collective desire to build on their understanding of mindfulness after the study.

Since trustworthiness of results is regarded as the bedrock of high-quality qualitative research (Birt et al, 2016), use of member checking for participant validation enabled the researcher to establish consistency between the study findings and the reflective views of the participants.

Discussion and conclusion

The principle findings were:

Analysis of the findings, which link occupational stress to prehospital care, are consistent with the body of academic literature, a notion wholly plausible given the unpredictable and traumatic nature of paramedic working (Mildenhall, 2012).

Although the limited appreciation of the health and wellbeing policy should naturally raise concern among managers, the evidence indicates that paramedics prefer to adopt less formal coping strategies when combating the detrimental effect of occupational stress (Regehr and Millar, 2007).

Interestingly, despite most paramedics reporting a limited knowledge of mindfulness as a health-promoting concept, given that two-thirds of those surveyed expressed an interest in the experimental phase of the study signifies a readiness to embrace new therapeutic approaches to occupational health.

Therefore, in view of the paucity of published literature linking mindfulness to prehospital care, a substantial opportunity exists to bridge the current gap in existing research.

Strengths and limitations

Though the investigatory phenomena of simply observing thoughts while remaining vigilant about self-bias naturally lends itself to the interpretative principles of qualitative methodology, evidence suggests that many of the empirically derived methods to inform mindfulness have not been formally validated (Burton et al, 2017; Guendelman et al, 2017).

Furthermore, while the adoption of member checking should be viewed as a genuine attempt to emphasise the key qualitative themes of neutrality, confirmability, consistency, dependability and transferability (Golafshani, 2003), the small sample size, threat of sampling bias, individual review of thematic content/coding and the singular focus on one region of the UK paramedic population collectively limit the study's generalisability.

Consequently, although the findings of this study appear encouraging, it is apparent that more longitudinal studies, involving rigorous recruitment techniques and active control measures are required to reliably inform this population group.

Implications for practice

Growing evidence suggests that mindfulness practice could revolutionise the health sector, preventing costly, long-term problems by providing staff with the mental health tools to cope with increasing levels of occupational stress (Collins, 2016). In the face of rising operational pressures, stringent budgeting restraints and the threat of political uncertainty, sustained integration of health improvement models within prehospital care appears logical.

Research findings advocate that the benefits of mindfulness extend beyond the individual. The Health, Safety and Wellbeing Partnership Group (NHS Employers, 2018) identifies that supportive manager behaviour, acknowledging positive contributions and constructive team culture as the organisational factors that influence employee health and wellbeing most. Since mindfulness has the potential to be combined with other models such as resilience training or leadership development, structured facilitation of mindfulness strategies may also benefit trusts through greater performance, lower performance variability and lower rates of absenteeism, resulting in a more focused and motivated workforce (Good et al, 2016).

Schemes such as the East Midlands Ambulance Service's My Resilience Matters programme (AACE, 2020) and the North West Ambulance Service's (2020) Invest in Yourself’ (2020) strategy are examples of good practice modelling that demonstrate the innovative ways in which NHS ambulance trusts are actively supporting the holistic wellness of their employees. In the same fashion, the award-winning, 8-week Staff Mindfulness Project by Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation Trust (2020) is further evidence of the ways in which trusts are reshaping organisational culture through health-promoting concepts designed to enhance personal wellness.

Although it is acknowledged that low levels of self-care could hinder paramedics, research suggest that interventions aimed at cultivating mindfulness have strong potential in the area of interpersonal functioning and may enrich feelings of empathy and compassion for oneself and others (Kingsbury, 2009). Moreover, with evidence reinforcing the notion that greater levels of self-care intrinsically correlate to better patient care (Burton et al, 2017), policymakers should take note of the substantial potential within the mindfulness concept.

Ultimately, the complex nature of prehospital working underlines the need for sustained implementation of health and wellbeing strategies. Proactively supporting the ways in which paramedics manage their occupational health will no doubt benefit them and their families through a greater quality of life, and also has the potential to make a considerable impact on the health outcomes of the patients they serve. JPP