Police officers and paramedics often share constant challenges in real time situations relating to consent and capacity. Capacity is largely questioned only when a person refuses treatment which is believed to be required in their best interests. Typically this leads to police and ambulance staff questioning a person's capacity when they do not agree with the suggested care plan or treatment decision. If it is not felt suitable to make the decision by the attending staff, then ideally the person on scene will be able to call upon further assistance via telephone or radio, or by requesting the attendance of a more experienced colleague or one with a more senior position. However, mental capacity and assessment of capacity benefit from understanding of the guiding principles of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (c.9) (MCA) and it is proposed that when they are applied, they make decision making more robust and confidence prevails.

It is not the purpose or the intention of this article to quote and draw down large pieces of information from the MCA as it is recognised that many provider organisations will have provided a session or update on the law. What this article aims to do is to set out key questions and considerations for paramedics and police officers to apply in times of challenge and to be able to root decisions within a reasonable understanding of the law as it presently stands.

Wooltorton Case Law

In September 2009, a young adult Ms Wooltorton drank antifreeze, dialled 999 and presented the attending ambulance staff with a letter dated 14 September saying she wanted no lifesaving treatment but would appreciate medicines to help with her discomfort (Smith et al, 2009). In the letter she said she was ‘100% aware’ of the consequences of her actions and accepted responsibility for them (not a legally valid advance refusal of treatment as it was not witnessed but powerful evidence of her wishes). When questioned by doctors she simply said, ‘It's in the letter.’ The hospital doctors caring for her at the time noted the clarity of her communication and instructions (David et al, 2010). They were clear that she did not consent to any invasive treatment carried out with the intention of saving her life. The on-call doctor followed due process and consulted the medical director, took legal advice, and consulted colleagues who had been treating her. The doctor believed that she knew that she would die if she refused treatment and that dialysis would save her life. Summing up HM Coroner stated that ‘the opinion of all concerned was that she was refusing treatment that could have saved her life and she was doing so with capacity and there was no way in which her capacity was impaired’ (Armstrong, 2009).

The staff considered that it would have been an assault to over-ride her wishes and said that a deliberate decision to die may be regarded as perverse or repugnant but that that did not mean that anyone had the right to over-rule the decision when made by an adult with capacity. (Re, S St George's Healthcare NHS Trust v S, 1998)

This case serves to demonstrate that decision making for consent to treatment and mental capacity can present as intertwined and often complex, and keeping up-to-date remains challenging. It highlights that it is no easy task to make a defensible and lawful decision in a stressful situation where time is of the essence. The feelings of the person involved and the differing views of any friends or family, and what seems right ethically to the paramedic all appear to be in conflict. Unfortunately, after events have unfolded and the incident is examined without the emotional pressures and stresses which influenced the decision at the time, it is only the facts which are examined. The real challenge is to bring the evidence base into practice and in this case the evidence base is the MCA.

Mental Capacity Act

The statutory principles apply to any act done or decision made under the Act. When followed and applied to the Act's decision-making framework, they will help people take appropriate action in individual cases.

The interface between the Mental Health Act 2007 (c.12) and Mental Capacity Act can present a challenge. There are some lessons that have been learnt from case law and Coroners' Court rulings that bring about practical understanding from what initially presents as complex, but less so on closer examination.

An interesting comment made by the Judge in GJ v The Foundation Trust (2009) was to apply the ‘But for’ test. ‘But for’ the physical disorder would the patient have been detained under the MHA? When the MHA applies it has primacy over the MCA and professionals cannot pick and choose which legislation to apply. Therefore, an understanding of the MHA is required. However, in a more recent ruling Mr Justice Charles stated the decision maker must take a fact sensitive approach and adopt the least restricted regime (AM v (1) South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and (2) The Secretary of State for Health, 2013), so clearly an awareness of both the MHA and the MCA is a requirement for all front-line professionals.

Process considerations on mental health decision making

The Mental Health Act 2007 (c.12) legislated various changes to the MHA of 1983. Fundamentally, the amended MHA brought about a single broad definition of mental disorders which is now ‘any disorder or disability of the mind’. The only excluded groups are those with a sole problem of drug and or/alcohol dependence (but those with drug and alcohol issues may also have a form of mental disorder as a consequence of the dependence or masked by the misuse as in self-medicating). In order that someone can be considered for detention under the MHA they must also have one of the following factors to accompany the diagnosis of a ‘disorder or disability of the mind’: for the protection of other people, or in the interests of his or her own safety, or in the interest of his or her own health.

It is also important to emphasise it is not ‘just if the person poses a risk to self or others’ but can also be in the interest of their own mental health providing that we know their mental health will deteriorate without treatment; this means this part of the criteria can only apply to people already known to services.

There is one more consideration to take account of when considering the use of the MHA: that is when a person has a learning disability. The MHA can only be applied if that person's disability is also characterised by ‘abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible behaviour’.

Section 135/136 Mental Health Act

They are covered here as police officers and paramedics are often drawn together and both should be aware of each other's role and powers available to them.

Section 136 (MHA) is the police constable's power to remove someone who appears to be mentally disordered and in need of immediate care or control to a place of safely for a period not exceeding 72 hours. This power is available for use when the person is in a public place, but not in their own home.

Where the person is in their own home and refuses access then this can only be facilitated by execution of a Magistrate's warrant, unless there is immediate danger to life or limb or an offence is being committed such as a breach of the peace, whereby the police have powers under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (c.60) (PACE). It may therefore be more appropriate to transport the person to an emergency department (ED) as the place of safety in an ambulance accompanied by the police if that is more appropriate under this power. The Code of Practice to the MHA (Ministry of Justice, 2008) states the decision on how best to convey the person should be made following a risk assessment carried out on the basis of the best available information.

Mental Health Act versus Mental Capacity Act

The case of Sessay (on the application of) v South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and Anor (2011) has been much debated and, it is proposed, largely misunderstood. The case concerned a woman who had been removed by the police from her own home to an ED (via the police station) utilising powers under the MCA. On arrival there was a misunderstanding of her legal status with the ED staff believing she had been arrested under s.136. Due to various problems she was kept in ED until finally detained under s.2MHA some 15 hours later. This detention period was challenged in court and the judge criticised the professionals involved stating that the MCA cannot be used where the powers under the MHA are available. It appeared to some that this statement meant that the MCA was no longer available when the person was in their own home.

It is asserted that what the judgement actually means is that the MHA must be used where it applies. For example, to gain access and remove someone from their own home requires a Magistrate's warrant which must be executed by an approved mental health practitioner, a doctor and a police officer (s.135 (1)). If there is no time to apply for this due to the urgency of the situation because a physical disorder cannot be ruled out, then to wait for this process to be undertaken for a person who lacks capacity to refuse is unnecessary and there is nothing to stop paramedics using the MCA in these circumstances.

That is to take the patient to an ED by force if necessary (which must also be reasonable and proportionate) to allow the hospital staff to undertake an urgent assessment of their mental or physical health if it is believed that this is in the person's best interests, and is considered the least restrictive option. This can be with the support of the police to protect the safety of the paramedic, but the paramedic can apply the MCA accordingly.

This would only allow for a limited period of confinement whilst formal arrangements for care and treatment could be made, a longer time frame could mean that staff cross that fine line moving from what merely restricts a person's liberty in their best interests, to a deprivation of their liberty which can only be authorised by the provisions of the MHA or the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DOLS) (Ministry of Justice, 2008). Friends, relatives or carers also have a part to play, in order to meet the best interests test they must be involved in the decision making, the paramedic as the decision maker in this situation is not bound by the views of others but must take them into consideration when making their decisions and record the evidence appropriately.

Applying the Mental Capacity Act

Difficulties also arise for the police and ambulance staff when the patient presents as needing treatment (for either a physical or mental health problem), is in their own home, and refuses to cooperate with the treatment being offered. This then presents the dilemma of whether the person has the mental capacity to refuse medical treatment as the first principle of the MCA states that all adults are presumed capable of making their own decisions and the third principle allows adults to make irrational or unwise decisions. This of course is often not as straight forward as treating an unconscious person in an emergency in their best interests.

A few cases have brought such complexities into the public domain and also the professional eye. The Wooltorton case highlights the issues of mental capacity and decision making, whereby antifreeze was ingested in a suicide attempt. This case is easier to examine after the events, but serves as an example of the conflicts mentioned previously between the clinical team, the family, and of course Ms Wooltorton.

The MCA states that although it applies to all people aged 16 years or over, there are certain exceptions for 16 and 17-year-olds; for example, they cannot donate a Lasting Power of Attorney nor create an advanced refusal as those with parental responsibility could in certain cases provide that consent; however, their pre-espoused desires must have serious account taken of them and may be included in advance care planning.

Where difficult decisions about serious medical treatment are being considered for an incapacitated person that has no friends or family to assist in those decisions, there is now the requirement to also involve an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA), this is a statutory requirement before decisions are made. However, this does not apply to emergency treatment, as it would be unreasonable to delay treatment to wait for an IMCA.

Refresher on mental capacity

A person is deemed to lack the necessary capacity to make that particular decision at that particular time if they cannot

If the person cannot meet all or parts of the above criteria this may call into question the person's mental capacity, it is for ‘others’ to establish incapacity in the balance of probability and not for the person to prove that they have it or not. Treatment of someone without mental capacity must be deemed in the person's best interests and also the least restrictive way of providing that treatment. Capacity can fluctuate and even at the very same moment in time a person can have mental capacity to consent to one area, but lack it in another. This forwards the important concept that capacity is decision and time specific at the time the material decision is required.

Back to Wooltorton

A Coroner's inquest concluded Wooltorton was legally competent (had capacity) to make her own decisions at the material time; however, this case highlights several ethical and practical problems in responding to the situation and also in times of crisis and high expressed emotion. It is difficult for professionals to make such objective decisions as more often than not what professionals consider is best may not match the wishes of the patient. As previously stated, it is when the person says no and goes against practitioners treatment plans that capacity is drawn into the frame, the MCA is about the person's best interests and not what we would want if we were that person making the decision.

The Wooltorton case is complex and emotionally charged and at the same time very sad for all involved; however, in some cases other treating staff may have overridden the patient's refusal and treated regardless, which highlights treatment complexities. The law does not set a threshold for these abilities to understand, retain, use and communicate decisions, nor stipulate that any combination of them must be in doubt. There is a legal presumption of capacity and although she was able to communicate her refusal of treatment, her decision seemed on the surface to be unwise and made more difficult by her refusal to discuss her reasons. Therefore, impaired use and weighing of information is also seen when there is a more persistent distortion of values, but had she been judged to lack the necessary capacity on any these grounds, it could have been lawful to give her life saving treatment provided it was agreed that this was in her best interests and the choice of treatment regime considered being the least restrictive.

Where there is doubt about capacity and time allows then an emergency application to the Court of Protection should be made. It might be argued that the use of the MHA could have been an option as the amended Act emphasises that treatment should be appropriate rather than necessarily curative and can address ‘symptoms’ and ‘manifestations’ of the disorder but this argument is for another arena. However, individual practitioners should consider each case on its merits and though useful case law, it is not possible to provide definitive direction from this case.

Mental capacity and protection for staff making decisions on behalf of those they believed to be mentally incapacitated

When carrying out acts of care and treatment in the best interests of a person who lacks capacity, staff will be legally protected. This means that staff will be protected under Section 5 of the MCA against legal challenges (but not if they act negligently), provided they:

If staff undertake this process in good faith then they receive the protection under the Act, provided treatment is no more than is reasonably required in the best interests of the patient before they recover capacity, or is necessary to save life, ensure improvement or prevent deterioration in physical/mental health. Of course accurate documentation of situation and condition-specific determination of mental capacity is essential.

Duty of care within MHA or MCA

The Mental Health Act provides a legal framework that can place potentially lethal self-harming behaviour within the context of mental disorder that justifies involuntary assessment and treatment (sectioning). All the additional safeguards and agreements for the relevant section of the act would need to be put in place.

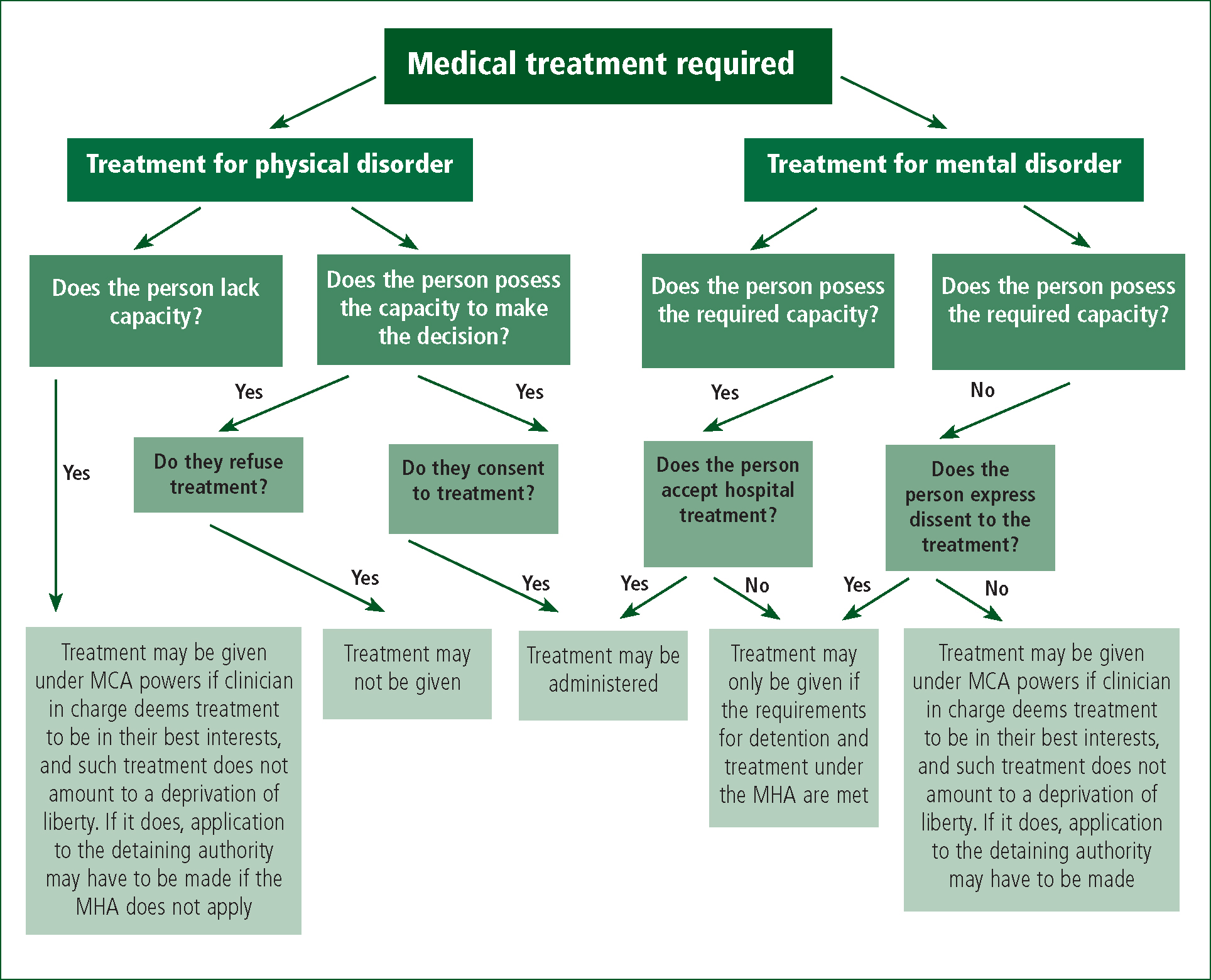

Use of the Mental Health Act might then permit the necessary lifesaving intervention depending on the meaning attributed to treatment for mental disorder. In cases heard before the recent amendments to the Act the Courts have been prepared to regard nasogastric feeding in cases of anorexia nervosa and borderline personality disorder as such treatment (B v Croydon, 1995), but more recently these types of decisions, where they relate to people deemed not to have decision-making capacity have been referred to the Court of Protection. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of capacity decision making and draws together the process and case law within this article.

Summary and conclusions

If you believe it is necessary to do something connected to a person's care or treatment, then you either need their consent, or if they lack capacity to consent, you can act in their best interests where there is no pre-espoused or documented wishes to the contrary.

If the person lacks the necessary capacity and is at risk of harm, then they can be restrained in their best interests providing the action is a proportionate response to the likelihood and seriousness of the harm. It should be noted that such restraint and deprivation of liberty is not limited to police officers, but paramedics and other clinicians too. The use of a police officer is to be considered after a risk assessment is made on the ambulance clinician's own ability to apply the level of restraint needed and in consideration of their own, and public safety. This intervention is never taken without other options being considered in the first instance and the reasons behind acting must be based within the guiding principles of the Acts.

If indefensible decisions to treat or deprive liberty are made, and the person has full capacity, then an assault charge or civil case maybe brought. It is important to emphasise the point again here that if the person has mental capacity and they fully understand the consequences of the act/action they are taking and they are an adult then it is their decision to make. ‘Reasonableness’ is considered when reviewing such decisions, in that if a clinician genuinely believed that they lacked capacity at that time and taken reasonable steps to assess capacity acting in the best interests of the person.

This case of Ms Wooltorton further highlights the provisions of the MCA and the need for continued training in capacity assessments, by adhering to the five guiding principles of the MCA assisted in the decision-making process, protected the rights of the person and staff. This was an influential Coroner's ruling who has considerable experience in mental capacity; however, with the benefit of hindsight and consideration of the MHA and MCA others may have acted differently. Although this is a lot easier to challenge when not involved in the case and all the circumstances we must fully acknowledge and respect clinical decisions made following correct processes.

Finally, the more complex the decision the more documentation is required and the aim of this piece has been to merge law practically and allow staff to question practice in times of challenge to inform decision making.