Ambulance services across the UK are enduring increasing, unsustainable demand on emergency medical services (EMS) (Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015). much of this rising demand involves mental health calls (Irving et al, 2016; Sands et al, 2016; Emond et al, 2019), and issues can range from a relapse of a serious mental illness through to self-harm or a crisis related to social issues or relationship breakdown.

It has been reported that community mental health teams are overloaded and unable to cope with the demand, especially when a person is having a mental health crisis (Ford-Jones and Chaufan, 2017; Rees et al, 2018; Emond et al, 2019). With such overstretched community mental health teams, it has been suggested that, in many cases, EMS are providing a safety net for people in crisis (Knowlton et al, 2013).

In the context of rising demand across the system, it is therefore important to explore how mental health calls are managed and understand how EMS can improve outcomes for people.

The aim of this service evaluation is to explore the thoughts, feelings and educational requirements of generalist paramedics and nurses (i.e. those without a mental health background) working on the EMS clinical desk, focusing on calls related to mental health and the triage tools used.

Background

This service evaluation sought to uncover paramedic and nurse perceptions of mental health 999 calls, and to understand how they are triaged by the Welsh Ambulance Service Trust's (WAST) clinical support desks.

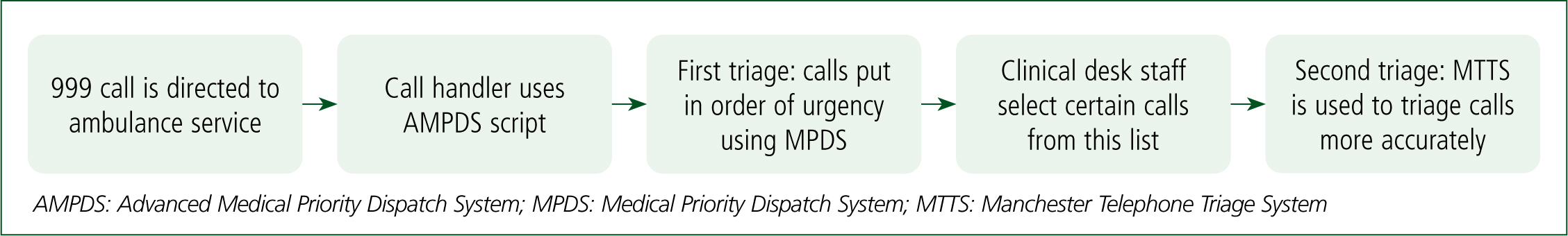

The word ‘triage’ is derived from the French word trier and means ‘to sort’ and ‘to select’ (Williams, 1996). In this context, triaging is a method of prioritising calls that need the most urgent attention. Initially, calls are triaged by a 999 call handler who follows a structured system called the Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System version 13.1. Next, calls are selected by the clinical support desk (made up of experienced paramedics and nurses); based on clinical experience, they essentially select the calls they feel most able to triage effectively. Their aim is to more accurately triage calls, offer alternatives to ambulance response (such as primary care) and alter disposition to a more appropriate response (e.g. escalation or alternative transport). This process is shown in Figure 1.

Professionals working on the clinical desk use the Manchester Telephone Triage System version 4.2 (MTTS) (Mackway-Jones et al, 2014). This has specific sections (called cards) related to mental health calls: card 33 is for mental illness; card 35 is for overdose and poisoning; and card 40 is for self-harm (Mackway-Jones et al, 2014). One of the objectives of this service evaluation focuses on these mental health-related MTTS cards.

A major component of triaging mental health calls is the assessment of risk. This risk is the likelihood of an adverse outcome happening in the context of mental health alone (Tate and Feeny, 2012), and there are many domains of risk to consider, including risk to the self (e.g. self-harm, suicide and neglect), to others (e.g. violence and aggression) or from others (e.g. physical or psychological abuse). Accurate assessment of these risks is key to good mental healthcare. A quarter of patients who die by suicide attended hospital as a result of self-harm in the preceding year (Cooper et al, 2008) and the risk of suicide is 30- to 100-fold higher in the year following an episode of self-harm (Chan et al, 2016). However, most people who self-harm do not go on to suicide.

On the face of it, recognising and assessing these risks in a comprehensive manner requires the identification of modifiable risk factors that allows staff to stratify people into low, medium and high-risk groups, so suicide prevention methods can be initiated and unnecessary service provision for low-risk patients avoided (Velupillai et al, 2019).

However, the science of risk assessment is still relatively immature. Quinlivan et al (2017) found that actuarial scales used to determine risk following an episode of self-harm performed no better and sometimes worse than clinicians' or patients' ratings of risk. They were deemed to be of limited help in clinical settings and risk wasting valuable resources (Quinlivan et al, 2017).

Aim and objectives

The main aim of this service evaluation was to explore clinicians' thoughts and feelings around the management of mental health calls.

The objectives were:

Ethical approval

The Health Research Authority decision tool was used and, as this study was identified as a service evaluation, ethical approval was not required (Medical Research Council and NHS Research Authority, 2021).

Methods

To gain an initial understanding of how the clinical contact centre operates, clinical desk processes and routines were observed for 1 week. This was followed by a review of the literature on the triaging of mental health emergency calls and paramedic experience with mental health calls.

Following this, four key themes were established: perceptions of mental health calls; triage and risk assessment tools; referral options; and additional training. These domains were then used to develop a questionnaire, which was piloted with clinicians to establish construct validity. The questionnaire can be found in Appendix 1 (online). This questionnaire was distributed to all clinicians working on the clinical desks at the three WAST clinical control centres. A covering letter explained the purpose of the questionnaire and stated that participants would be anonymous. Of a total of 41 practitioners, 26 completed the questionnaire.

Data were inputted into Microsoft Excel 2016 and analysed using the following descriptive statistics: mean; standard deviation; median; and percentage. A main conclusion was established for each key theme (Table 1). Qualitative data were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2008). Of the qualitative data, 90% were double coded blindly to determine codes. Once discussed and decided upon, all data were coded using line-by-line thematic analysis.

| Questions | Median | Mean | Disagree/strongly disagree | Neutral | Agree/strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I feel confident in handling mental health (MH)-related calls | 3 | 2.62 | 35% | 54% | 12% |

| I have had sufficient training in how to handle MH-related calls | 2 | 1.88 | 73% | 27% | 0% |

| Most of my knowledge around how to handle MH calls comes from my previous experience working face to face with MH patients | 4 | 3.81 | 12% | 15% | 73% |

| Calls for physical health problems are resolved more quickly than those for MH problems | 4 | 4.12 | 8% | 8% | 85% |

| Part of my role as a clinician on the clinical desk is to support those in an MH crisis | 4 | 4.04 | 8% | 12% | 81% |

| My previous face-to-face encounters with MH patients makes me more likely to take an MH-related call from the stack | 3 | 2.96 | 42% | 23% | 35% |

| My previous telephone triage encounters with MH patients from working on the clinical desk make me more likely to take a MH-related call from the stack | 3 | 3.08 | 31% | 35% | 35% |

| The current call stack being busy makes me more likely to take a MH-related call from it | 2 | 2.42 | 62% | 23% | 15% |

| I feel confident in managing someone who is currently self-harming | 3 | 2.73 | 50% | 23% | 27% |

| I feel confident in managing someone who is currently feeling suicidal | 3 | 2.77 | 35% | 38% | 27% |

| I believe that the current provisions provided by community mental health services result in more MH related calls. | 5 | 4.50 | 4% | 0% | 96% |

| They* are thorough and in sufficient detail | 2 | 2.35 | 58% | 31% | 12% |

| By sticking closely to them*, I feel safe from any litigation in case of an adverse outcome | 2 | 2.31 | 54% | 35% | 12% |

| They* accurately assess the level of risk from the patient | 2 | 2.12 | 62% | 35% | 4% |

| They* accurately assess the level of risk to the patient | 2 | 2.19 | 58% | 35% | 8% |

| They* direct me towards the outcome that is best suited to the patient | 2 | 2.04 | 73% | 27% | 0% |

| At times I refer MH patients to A&E due to lack of other referral pathways | 5 | 4.38 | 0% | 13% | 88% |

| It is easier to manage patients who are already known to MH services | 4 | 3.33 | 33% | 17% | 50% |

| I feel frustrated with the lack of referral options for MH patients | 5 | 4.58 | 0% | 8% | 92% |

| I am confident that referring a MH patient for a GP review ensures the patient receives the most appropriate management | 2 | 2.42 | 58% | 29% | 13% |

| I am confident that referring a MH patient to accident and emergency ensures the patient receives the most appropriate management | 2 | 2.25 | 71% | 17% | 13% |

| I am confident that referring a MH patient to the crisis team ensures the patient receives the most appropriate management | 3 | 3.35 | 26% | 30% | 43% |

| Clinical placement in MH would help support me to manage MH calls | 4 | 4.19 | 4% | 19% | 77% |

| MH training would help support me to manage MH calls | 5 | 4.46 | 0% | 8% | 92% |

| Working more closely with MH call services (e.g. Samaritans) would help support me to manage MH calls | 4 | 3.96 | 12% | 12% | 77% |

Codes were organised in order of frequency per question: the three most frequent codes per question can be seen in Table 3. Quotes from open text boxes are used to contextualise data.

| Nurses | Paramedics | Unidentified |

|---|---|---|

| 13 | 12 | 1 |

| Total n=26 | ||

| Questions | Three most common codes and their frequency |

|---|---|

| How much mental health training have you had in your career? | Minimal: 14 |

| Clinical placement: 6 | |

| Mental health first aid day: 6 | |

| Have you been on any mental health training days through Welsh Ambulance Service Trust? If so, what? | None: 11 |

| Applied suicide intervention skills training (ASIST): 9 | |

| Awaiting ASIST: 3 | |

| Are there any other factors that make you more likely to take a mental health-related call from the stack? If so, what are they? | Overdose: 6 |

| Patient safety at risk: 2 | |

| Self-harm: 2 | |

| Police present: 2 | |

| Should mental health calls be dealt with by emergency services? | Yes, if immediate threat to life: 9 |

| Yes: 6 | |

| Sometimes, depends on reason: 5 | |

| What is your opinion on having a mental health trained nurse on the clinical desk dedicated to mental health calls? | Beneficial: 25 |

| 24-hour cover needed: 3 | |

| Helpful reference for other staff: 2 | |

| How could the mental health-related Manchester Telephone Triage System cards be improved? | More detail: 6 |

| Mental health professional input: 3 | |

| Develop referral pathways: 2 |

Findings

Almost two-thirds (63%) of potential participants returned the questionnaire, which exceeded expectations by a significant margin. This group is a convenience sample in one service and there were no power sample calculations. The group comprised 13 nurses and 12 paramedics, with one person's role unidentified (Table 1). Results from the quantitative part of the questionnaire can be found in Table 2.

All results were put into the categories of: staff confidence; triage and risk assessment; referral options; and future training and support.

The results from the qualitative feedback can be found in Table 3 and are throughout the categories to contextualise, reinforce and triangulate results. Conclusions from each category can be found in Table 4.

| Staff confidence and perceptions | Triage and risk assessment tools | Referral options | Future training and support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinicians' low levels of confidence in managing mental health calls reflects the reported lack of training | The Manchester Telephone Triage System mental health cards lack enough detail and do not accurately assess risk | There is a lack of referral options causing staff to refer patients to accident and emergency although they have little confidence that patient will receive the most appropriate management. Staff have the most confidence in crisis resolution teams | Mental health training and placement would be valuable in aiding mental health call management. A mental health trained nurse on the clinical desk would also be beneficial |

Staff confidence and perceptions

One-third of staff reported very low levels of confidence and the majority (88%) were not confident in managing mental health calls. This perhaps reflects the fact that almost three-quarters of the respondents (73%) felt they had not had enough training in how to handle calls related to mental health.

The majority (85%) found physical health calls were resolved more quickly and therefore, on busier days, mental health calls were less likely to be chosen for further triage (62%).

Nearly all staff (96%) agreed that the lack of provision by community mental health teams resulted in more mental health-related calls to the 999 system.

Triage and risk assessment tools

Only 12% of participants found the MTTS mental health cards were sufficiently detailed and no respondent agreed they directed clinicians to the best outcome for the patient:

‘I feel the cards are vague in nature and the discriminators rarely help to assess the patient.’

Most felt the MTTS mental health-related cards did not provide an accurate assessment of risks to (62%) or from (58%) the patient. In the open text boxes, three staff suggested that improving the mental health elements of the MTTS required input from a mental health professional.

Referral options

Most (92%) staff said they felt frustrated with the lack of referral options. Out of the three referral options in the questionnaire—GP review, accident and emergency (A&E) and the crisis resolution team—staff had the most confidence in the crisis resolution team for providing the most appropriate management for the patient. However, they could not always be accessed:

‘It is rare that we can directly refer to crisis teams.’

Only 13% felt confident that GPs and A&E would provide the most appropriate care, with the least confidence in A&E—71% disagreed that they were confident in the outcome of referring to A&E, compared to 58% for GP review. The majority (88%) of staff agreed that at times they referred mental health patients to A&E because of a lack of other referral options:

‘[We need] better mental health care pathways—patients end up in [the emergency department, which is] not the best place for the patient.’

Future training and support

Nearly all (92%) of staff agreed that mental health training would help them to manage mental health calls and 77% thought clinical placement in mental health settings would do the same. A response to the space for further comments echoed this:

‘Further training is an absolute necessity for us.’

Almost all (90%) believed having a nurse trained in mental health on the clinical desk would be beneficial:

‘[This is] desperately needed.’

Two staff added that nurses trained in mental health would provide a helpful reference for other staff, hence improving their practice:

‘They have more knowledge and contacts than are known to myself.’

However, three staff suggested that 24-hour cover would be needed for it to be fully effective.

Discussion

Staff confidence and training

One of the main findings of this service evaluation was the participants' low level of confidence in handling mental health presentations, something that Rees et al (2018) found paramedics also experienced during face-to-face consultations. This perhaps has its origins in the reported low levels of training for clinical support desk professionals.

Practitioners also thought clinical placements to provide them with experience of working with patients during a mental health crisis would be beneficial.

Given on the results of this evaluation, WAST is co-designing a programme of learning, development, placements and evaluation with clinical support desk professionals.

A new risk assessment tool?

Overall, staff felt the MTTS was limited in its utility as a triage tool for mental health calls. Once physical health discriminators have been cleared, the remaining discriminators ask for an assessment of risk of self-harm or harm to others but offer no support to clinicians in how to undertake these critical assessments.

A wide range of risk assessment tools are used in clinical practice across the UK (e.g. SAD PERSONS Scale (Patterson et al, 1983), the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al, 1961) and the Threshold Assessment Grid (Slade et al, 2000); however, a study of 32 hospitals in England found locally developed proformas were used most commonly instead (Quinlivan et al, 2014). The Royal College of Psychiatrists recommend that locally developed risk assessment methods should not be used as tools should be ‘evidence based and widely validated’ (Alderdice et al, 2010). Risk assessment tools are helpful because they are easy to administer and require less experience than assessing through clinical judgment but research suggests their effectiveness is limited (Large et al, 2016; Quinlivan et al, 2017). The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence recommends that risk assessment tools should not be used to predict the risk of suicide or self-harm (NICE, 2019).

Risk assessment tools are mostly designed for use in mental health rather than unscheduled care settings. In 2011, 11% of calls attended by the Scottish Ambulance service were mental health or self-harm coded patients (Duncan et al, 2019). This is a significant proportion of paramedic's workload but, despite this, minimal research has been carried out into paramedic's decision-making during face-to-face assessments in this area (Shaban, 2006).

Risk assessment over the telephone comes with an additional set of challenges: clinicians cannot pick up on non-verbal cues (a key part of the examination of a patient's mental state) nor see what the patient is doing, which is particularly important in the contexts of self-harm and suicide. With an estimated 800 000 people dying from suicide globally each year, it is imperative that those at risk can be identified (World Health Organization, 2019).

Some detailed thinking is required on how a specific risk assessment tool can be developed that guides good assessment practice while steering practitioners away from attempting to predict risk levels.

Lack of referral options

A common theme in the literature surrounding mental health management by emergency services is the lack of referral options (Irving et al, 2016; Rees et al, 2018; Duncan et al, 2019; Emond et al, 2019); this theme was reflected strongly in the findings of this service evaluation.

Emond et al (2019) found that paramedics reported difficulty in contacting mental health services. One clinician echoed this, reporting that difficulty in referring patients directly to crisis resolution teams was common. Working more closely with community mental health teams and crisis resolution teams could help bridge this gap. However, ambulance staff may not be aware of the original (and in some cases the current) remit of crisis teams, which is to support people who already have a mental illness diagnosis and are in receipt of specialist mental health services. The assumption that mental health crisis teams have the remit and capacity to take on unknown clients can lead to expectations that will often not be met.

Regardless, there is a degree of consensus that people often refer mental health patients to A&E because other referral options are lacking, a theme well documented in the literature (Irving et al, 2016; Rees et al, 2018; Duncan et al, 2019; Emond et al 2019). Duncan et al (2019) reported that in Scotland more than half of mental health call patients went to A&E and were discharged or left at home (likely because of refusal). In addition to this, one-fifth of those who went to A&E self-discharged and were 25% more likely to call again than those who remained and completed treatment (Duncan et al, 2019). This shows that, although A&E is often the only option, it may not be the most appropriate one.

Although not considered in this study, alcohol is likely to be a significant factor in many calls to emergency services (mental health calls in particular).

Effects of overburdened community mental health teams

Most staff felt that under-resourcing in community mental health teams resulted in more calls related to mental health.

This fits with literature reporting overloaded community mental health teams (Ford-Jones and Chaufan, 2015; Rees et al, 2018; Emond et al, 2019) and the knock-on effect of more 999 calls as a result (Ford-Jones and Chaufan, 2017; Rees et al, 2018; Duncan et al, 2019).

In a qualitative study by Rees et al (2018), paramedics suggested certain mental health crises were worsened by patients having been unable to access services sooner. Emond et al (2019) suggest restructuring services to create a closer working relationship between community and emergency services and allow a more effective response to the large volumes of calls

A new role for mental health nurses?

The suggestion of a mental health-trained nurse working on the clinical desk was well received. A pilot project involving mental health-trained staff working in the emergency operations centre of Yorkshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust found this reduced the number of ambulances dispatched and the number of A&E admissions for mental health calls (Irving et al, 2016). However, it is still unclear whether this is the most cost-effective means of triaging mental health calls.

Strengths and limitations

While useful, this service evaluation has some significant limitations, including the sample size: 26 of 41 potential participants completed the questionnaire. The time scale was short so the questionnaire was live for only 10 days, which meant not all staff may have had the opportunity to complete it.

There were no established survey instruments, so the questionnaire was designed independently for this service evaluation, limiting its reliability, validity and standardisation.

The small sample size limits the conclusions that can be drawn beyond this group and generalised to other services. Further research is needed with a larger sample size over multiple ambulance services.

Strengths of this study included the qualitative data, which add a deeper layer of understanding and prompted clinicians to propose ideas on how to improve the service.

Bias was reduced by blindly double coding 90% of qualitative data. Although 26 is a small sample size, this was out of a total of 41 clinicians so the response rate was high at 66%. Ensuring anonymity reduced bias and may have boosted the response rate.

Finally, having input from multiple supervisors in the development of the questionnaire as well as piloting it before use improved its validity.

Conclusion

With the growing number of mental health calls to 999 services, systems, processes and education are still trying to keep up with this demand.

This survey found low levels of confidence in handling mental health calls, a lack of training, frustration with the lack of alternatives to A&E admission, and risk assessment tools and processes that are not up to the job. These issues are now a high priority for leaders in WAST but, clearly, more can and should be done if they are to keep pace with the changing nature of their work and meet the needs of the populations they serve.

Many ambulance trusts are developing services to improve their responses to mental health calls, some of which focus on recruiting mental health professionals into the emergency services environment. This study suggests there is considerable scope to build upon and improve the service as it stands through improving the skills and confidence of nurses and paramedics working in it now.

Work is required to establish the volume of calls to emergency services where alcohol is an exacerbating factor.

WAST is undertaking a programme of work to improve the mental health skills and confidence of clinicians working in telephone triage settings, and the trust (and other ambulance services) should encourage triage software suppliers to take mental health telephone triage more seriously and build robust risk assessment tools into their systems.

WAST and local mental health providers continue to look for ways to collaborate on developing crisis care systems that support better outcomes for the populations they serve. In its recent 3-year delivery plan for mental health, the Welsh Government (2019) has signalled its intent to develop a standardised model of crisis care across the country. This opens up opportunities to develop more integrated, innovative and evidence-based approaches to crisis care, with WAST, the police and other blue light services at the table from the outset.