In healthcare, the general attitude towards error is the ‘person approach’ (St Pierre et al, 2008). The person approach attributes fault or blame with the healthcare provider if an error occurs. It is often believed that the error occurred due to a lack of knowledge, or that the clinician did not pay attention, or did not do their best. This viewpoint inevitably results in a culture of naming, blaming and shaming; the solution is often to try harder (St Pierre et al, 2008).

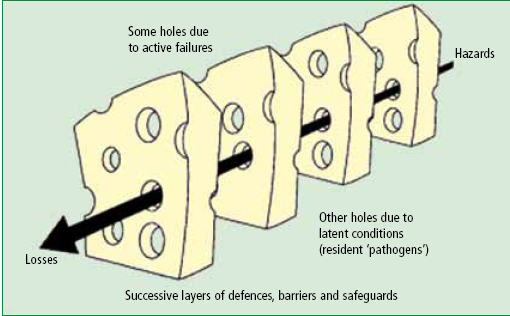

James Reason's famous Swiss cheese model (Reason, 2008) describe best how errors occur and emphasizes that both organizational and human factors have to be considered. Each layer of the cheese represents an organizational, personal or environmental defence, and each is imperfect as shown by the ‘holes’. For an accident to occur, latent conditions, active errors and local triggering events coincide (Figure 1).

On the other hand, a hazard may penetrate several layers of defence before it is stopped; in this instance, a near miss would have occurred. An example may be a clinician checking the contents of a vial to find the wrong drug had been selected prior to administering the drug.

What are non-technical skills?

Non-technical skills are one defence against error. Flin et al (2008) noted:

‘They are what allow the best practitioners to achieve consistently high performance and what the rest of us do on a good day’ (Flin et al, 2008).

According to Flin et al (2008), the non-technical skills found in most safety-critical occupations are:

Various studies to determine non-technical skills for particular professions have been conducted in high reliability industries such as nuclear power, the offshore oil industry, the military, and aviation (Kanki et al, 2010). More recently, research has been conducted by Aberdeen University psychologists’ working with clinicians into the non-technical skills of anaesthetists, surgeons and scrub practitioners (Industrial Psychology Research Centre, 2011a). Some of this type of work from the world of aviation is described in this article.

Lessons from aviation

In 1935, the US Army Air Corps held a competition for aircraft manufacturers to design a new modern bomber. The Boeing Corporation won the competition with its Model 299, nicknamed the Flying Fortress, and had produced an aircraft that could fly faster, further and carry 5 times more bombs than its rivals. On the 30 October 1935, a group of senior army officers and Boeing executives gathered to watch the aircraft taxi out on its test flight. The crowd watched as the aircraft took off and climbed to 300 feet before stalling; turning on its wing and crashing into the ground; killing two of the five crew, including the chief test pilot, Major Ployer Hill.

Following an investigation into the crash, pilot error was attributed as the cause of the crash. The aircraft was substantially more complicated to fly than any other aircraft of its time and required the pilot to carry out numerous simultaneous actions to keep the aircraft in the air. Due to the number of actions needed, the pilot had forgotten to unlock the rudder control, causing the crash. The aircraft was dubbed ‘too much aircraft for one man to fly’.

Despite the crash, the army ordered these aircraft and despite the army's chief test pilot not being able to handle the aircraft, the army did not require its pilots to carry out extra training. What they did was to create a checklist. The creation of a checklist acknowledged that to merely try harder was not a solution. In 1935, the US Army had realized that the weak part of the system was the human operator, the pilot (Gawande, 2009).

It was some years later before the aviation industry seriously began to address the human factors in safety. From the 1970s, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration conducted research that concluded that 70% of aviation accidents are caused by human error. This error rate is concurrent with the UK Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), who also report 70% of aviation incidents and accidents being attributed to human error (CAA, 2002). Parallels in safety between aviation and medicine have been made by the psychologist, Helmreich (2000) who wrote:

‘Pilots and doctors operate in complex environments where teams interact with technology. In both domains, risk varies from low to high with threats coming from a variety of sources in the environment’ (Helmreich, 2000: 781-5)

Summers et al (2011) described the concept of crew resource management (CRM), which is one of aviation's error avoidance measures. CRM training for pilots is a statutory requirement by both the CAA and the Federal Aviation Authority USA (FAA). The paper rightly reports that CRM training is not commonly received by paramedics. An exception to this may be paramedics who are employed on rotary or fixed wing aircraft, who may receive CRM training focusing on the flight aspect of their work. The CRM programme includes the checking of pilots’ CRM skills using a behavioural rating system, one of which is called non-technical skills (NOTECHS) (Flin et al, 2003).

According to the CAA (2006), there are four instances when a pilot would receive assessment of their non-technical skills: licence skill test, licence proficiency check, operators proficiency check, and line check. The non-technical skills of individual crew members are assessed with a behavioural rating system which provides a taxonomy of good and bad behaviours. The ratings made by an experienced examiner indicate the standard of the individual's non-technical skills.

Assessment of an individual's non-technical skills is made against a required standard with remedial training given to a crew member who falls below this standard. A crew member would not fail a licence test or proficiency check due to poor nontechnical skills alone, unless this was associated with a technical failure, such as a violation of standard operating procedures (SOPs) or failure to observe company policies (CAA, 2006).

Behavioural rating systems

Industrial psychologists have long been interested in the positive and negative behaviours that contribute to safety in a range of high stakes industries. Recently, the focus has been on medicine and patient safety. Among other specialties, one study involved anaesthetists—the anaesthetists non-technical skills (ANTS) used a number of task analysis techniques to develop a skills taxonomy and behavioural rating system (Appendix 2). One of the analysis techniques used was cognitive task analysis (CTA), applied to determine the positive and negative behaviours that contribute to safe anaesthesia in a theatre setting.

The CTA used specifically was a critical decision method (Fletcher et al, 2004). This method involves interviewing subject matter experts; in this case, consultant anaesthetists. The interviews were in three parts, semi-structured, and required the interviewee to freely recall a critical situation encountered. The interviewer then refines the interview by asking probe questions to specifically elicit information about the skills required for that situation. The second part of the interview centres on the expert describing the non-technical skills that are regarded as necessary to be a good anaesthetist. The third and final part of the interview process involved eliciting the anaesthetist's attitudes towards non-technical skills, and the link between them and their own technical tasks.

Interestingly, one of the questions asked was whether the non-technical skills were similar or different between normal or crisis situations. Of the 29 anaesthetists questioned, 20 felt that the nontechnical skills were basically the same; however, in the crisis situation, the skills would be exaggerated or extended.

The results from all the interviews, as well as observations, survey data and a literature review, were coded by the psychologists to identify a list of positive and negative behaviours related to safe and efficient delivery of anaesthesia. With a panel of consultant anaesthetists, a taxonomy of non-technical skills was developed, along with a rating scale to record them from observations. This was then tested in both experimental and usability studies. The preliminary and final taxonomy of behaviours were tested using ratings of behaviour from video simulations of anaesthetic procedures. Appendix 1 illustrates the common themes from the interviews.

PARAmedic NOn-Technical Skills (PARANOTS)

In addition to improved patient safety and error avoidance, an understanding of paramedic nontechnical skills could have a positive by-product for the clinical effectiveness of the profession. Non-technical skills should be a foundation to build on the current skill set of paramedics. Consider the recent article in JPP entitled ‘Rapid sequence airway not rapid sequence intubation’ (Sherlock, 2011). This describes the challenges to safe airway management by Tasmanian paramedics in the prehospital setting, using a range of airway adjuncts including paralysis, assisted insertion of supraglottic devices. The physical motor skills of airway insertion, laryngoscopy and intubation are relatively easy compared to the decision as to whether to carry the procedure out or not, or how to manage an instance of failure to ventilate. This sentiment is echoed in a quote from the article:

‘A paramedic rapid sequence induction (RSI) programme requires a supportive infrastructure…‥that includes cognitive and technical training’ (Sherlock, 2011)

Studies are underway to investigate the nontechnical skills that are applicable to paramedics working in the prehospital setting. Findings from this research will be used to develop a behavioural rating system similar to that of the ANTS system.

‘In addition to improved patient safety and error avoidance, an understanding of paramedic non-technical skills could have a positive by-product for the clinical effectiveness of the profession’

Non-technical skills in other aspects of the UK ambulance service

Although the interest of the author is the nontechnical skills used by paramedics on a day-to-day basis, the generic non-technical skills taxonomy, listed by Flin et al (2008), is equally applicable to other aspects of UK ambulance operations.

Conclusions

An understanding of non-technical skills in high risk settings such as aviation and anaesthesia has, and is contributing to, safe flight operations and anaesthetics. Although it is difficult to quantify safety errors ‘trapped’ by the use of positive behaviours in anaesthesia, aviation remains the safest form of transport. If the number of aircraft that ‘fell out of the sky’ was comparable to the number of NHS patients who were adversely affected during their treatment, airlines would have gone out of business long ago.

Despite being in a period of financial constraint, the safety of our patients should be at the pinnacle of paramedic prehospital care. The financial implications of error investigation, litigation costs, and lost staff hours could easily offset the cost of developing a non-technical skills training package that, if endorsed by the Health Professions Council and College of Paramedics, could be rolled out to all prehospital emergency care clinicians.

The training of non-technical skills, as well as primarily contributing to patient safety, would establish the foundations for future paramedic skill set development, and could be used as a positive mechanism to improve operations, EMDC, major incident management and clinical effectiveness.