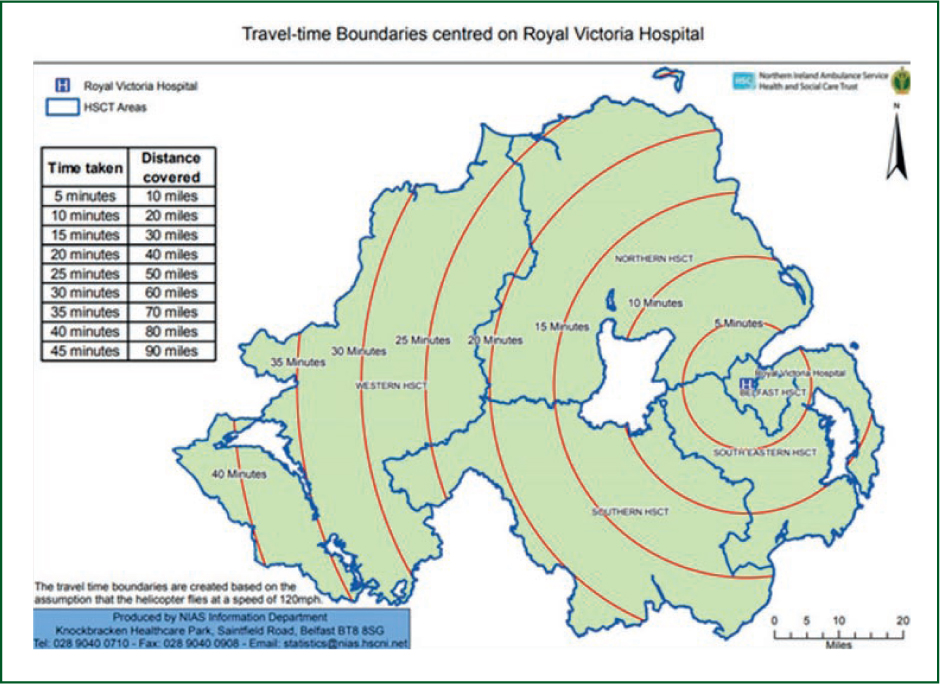

The Northern Ireland (NI) Ambulance Service began operating a helicopter emergency medical service (HEMS) in July 2017 and has provided the region with a single, helicopter-based prehospital care team since. The running of NI HEMS is supported by the work of publicly funded charity Air Ambulance Northern Ireland. NI HEMS operates in daylight hours, 7 days a week and responds to emergencies either by helicopter (Helimed 23) or via a ground-based rapid response vehicle (rapid response vehicle Delta-7) as appropriate. Care is delivered by a two-person team composed of a paramedic and a consultant physician. The service operates alongside ground-based ambulance crews and other emergency services covering the whole of NI, which has a population of approximately 1.9 million (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2021). Figure 1 shows approximate flight durations and distances across the region.

The delivery of patients via Helimed-23 to the regional major trauma centre at the Royal Victoria Hospital emergency department (RVH-ED) has changed since the NI HEMS became operational. Initially established as a trauma-focused service, it has now evolved into a prehospital emergency medical service.

Before 18 February 2022, patients being transported by helicopter were airlifted to the nearby Musgrave Park Hospital in Belfast then transported 4.4 km by ground ambulance to the RVH-ED. Since this date, the RVH-ED has had an operational helipad on the roof of the building allowing for direct transport and patient offload. Not all patients undergoing prehospital emergency anaesthesia (PHEA) are transported to the major trauma centre.

All NI HEMS physicians are at consultant level with an emergency medicine, anaesthetics or intensive care background, and have had additional training in the delivery of prehospital care. NI does not provide a prehospital emergency medical training programme so doctors below consultant grade are not part of the service. Paramedics undergo additional specific training when they are recruited to the service. This training is standardised to cover key competencies needed for the safe delivery of PHEA; both team members play a vital role in this.

Emergency calls are received and processed by emergency ambulance control, with the NI HEMS air desk paramedic selecting appropriate calls and dispatching the HEMS team. The NI HEMS team is tasked to attend both major trauma and medical emergencies, providing expertise in a range of interventions, including the delivery of PHEA in the form of rapid sequence intubation (RSI) and sedation.

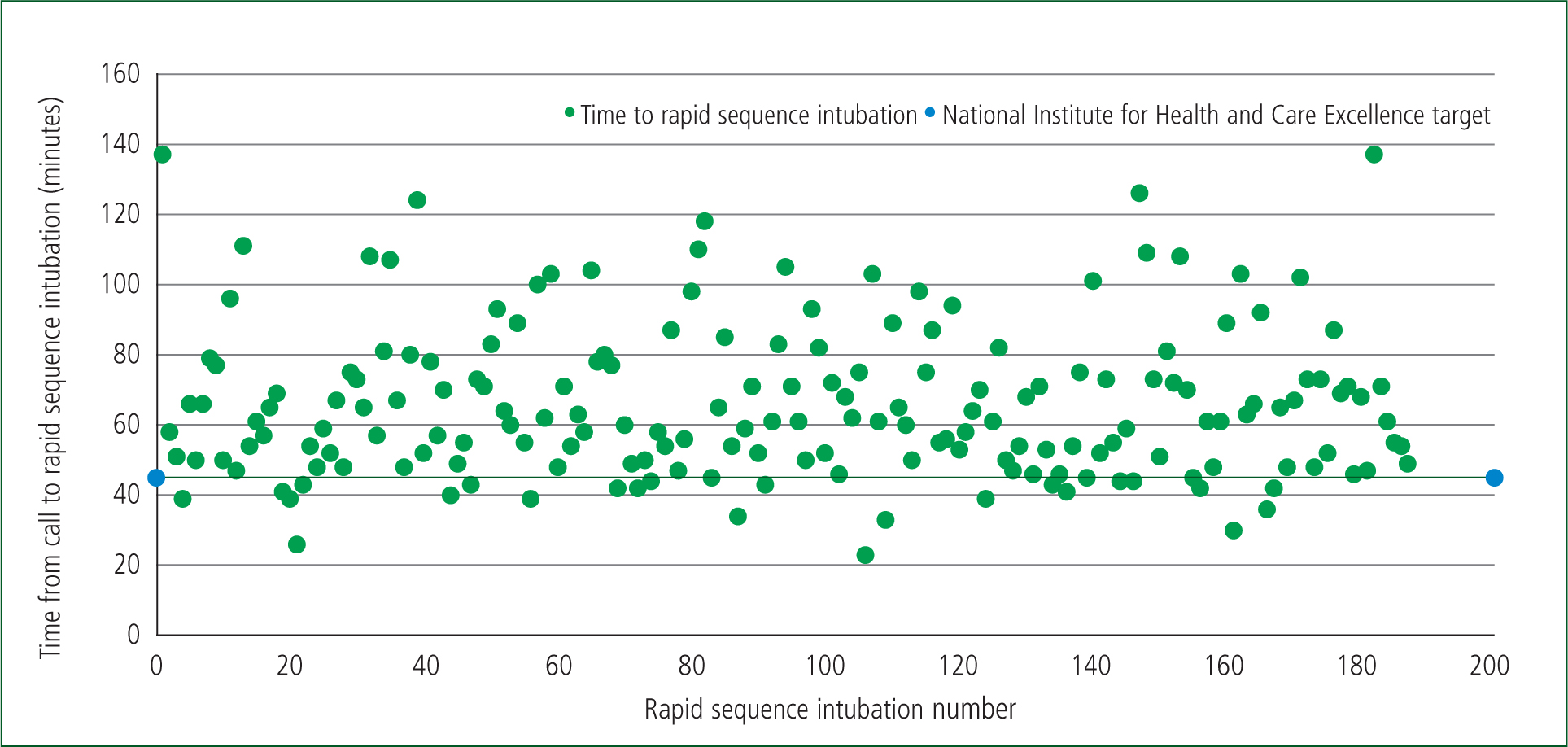

The delivery of PHEA, as with in-hospital anaesthesia, should be done in a safe and robust manner and, to that end, a standard operating procedure (SOP) was developed in line with best practice (Crewdson et al, 2019). This SOP, along with an intubation log, was to ensure PHEA delivery was appropriate as well as facilitate clinical governance regarding safety so all cases of PHEA could be reviewed and audited (Appendix 1, online). The target for delivery of PHEA is within 45 minutes of the incident call (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2016).

The SOP, developed in line with the London Air Ambulance Service, includes indications for performing PHEA but also states that this decision is taken on a case-by-case basis (Aziz et al, 2021). These indications are: actual or impending airway compromise; ventilatory failure; unconsciousness; humanitarian need; critically ill patients who are unmanageable or severely agitated; and anticipated clinical course. Choice of drugs for induction, checklist for intubation and guidelines for failed intubation are all included in the SOP.

The SOP and the intubation log have both been updated since their introduction. They now include more quantitative data, including blood pressure variations and oxygen saturations, along with a record of drugs used for the maintenance of anaesthesia (Appendix 1, online).

Methods

All intubations carried out by the HEMS team have been recorded contemporaneously in a dedicated RSI log since the service came into operation. They are documented on a paper pro forma before being uploaded to a single database (historically, this involved a spreadsheet but now a digital app is used to allow for real-time updates). The intubation log pro forma was reviewed and updated three times between July 2017 and February 2021. Data included in the log are in keeping with the international consensus on reporting prehospital advanced airway management (Sollid et al, 2009).

Measured data include: the location of the incident; dispatch method; patient demographics; RSI indication; drugs used for RSI; number of intubation attempts; grade of view; clinician initials; time to patient from call; time to RSI; times at scene; and any issues.

A retrospective review was conducted, which examined all instances of PHEA carried out between 29 July 2017 and 28 February 2021. Statistical software R version 4.2.0 was used for carrying out all statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics, frequencies and graphs were produced, and statistical significance was measured using the Wilcoxon test and Fisher's exact test. Differences were considered statistically significant at α=0.05 level.

Exclusion criteria

Cases of PHEA were excluded from analysis if they were not undertaken as a drug-assisted intubation or had an incomplete dataset in the database.

Results

A total of 200 episodes of intubations occurred between 29 July 2017 and 28 February 2021. Each of the records were reviewed; 13 records were missing data on grade of intubation and number of attempts at intubation.

For analysis, all 200 records were included except for analysis of grade of intubation or number of attempts at intubation, when the 187 completed records were used.

Patient demographics appear in Table 1. Of 200 cases, patients were predominantly male (145; 72.5%), a significant difference (P≤0.0001). The proportion of women was 27.5% (95% CI (21.6–34.3%)). Further analysis of demographics showed no statistical significance in the ages of men and women treated (P=0.5544). The largest cohort by age were those aged ≥70 years (20%). Most RSI cases occurred outside the Belfast city area (170 cases; 90.9%).

| Demographic | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||

| 0–4 | 1 | 0.5% |

| 5–9 | 3 | 1.5% |

| 10–17 | 11 | 5.5% |

| 18–29 | 33 | 16.5% |

| 30–39 | 31 | 15.5% |

| 40–49 | 21 | 10.5% |

| 50–59 | 33 | 16.5% |

| 60–69 | 27 | 13.5% |

| ≥70 | 40 | 20% |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 145 | 72.5% |

| Female | 55 | 27.5% |

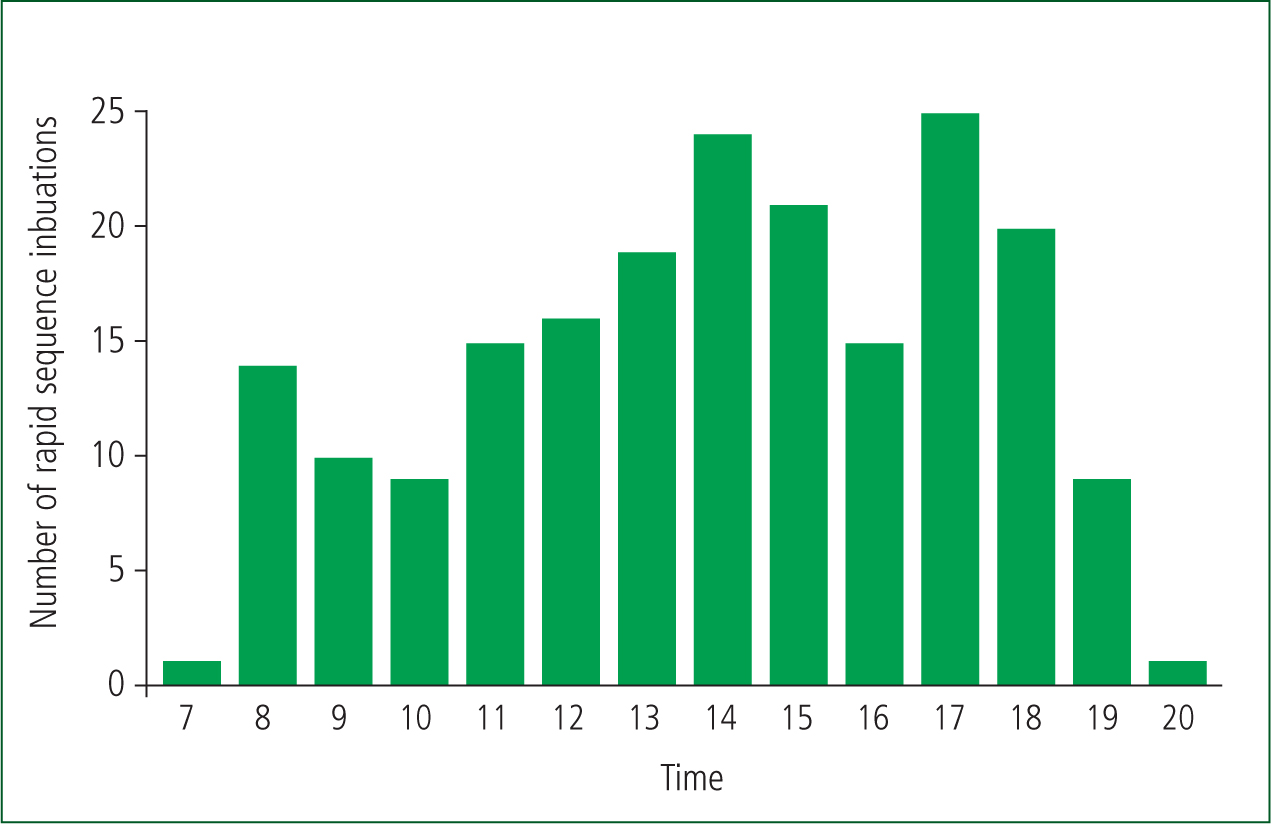

No associations were found between the number of call-outs involving RSI and month of the year (P=0.4466) or season (P=0.1808). However, there was an association between the number of RSI events and the time of the day they occurred, with more RSIs being carried out between 14:00 and 17:00 (P≤0.0001) (Figure 2).

Indications for intubation, which were developed in line with other UK HEMS, were reviewed for each case (Table 2). Unconsciousness, in the context of a critically ill or injured patient, is one of those indications and accounted for 53% of cases (n=106). The next most frequently documented indication was ‘injured patients who are unmanageable or severely agitated after head injury’, who accounted for 23% of all causes (n=46).

| Indication | Number of cases | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Airway compromise | 19 | 9.5% |

| Ventilation failure | 19 | 9.5% |

| Unconsciousness | 106 | 53% |

| Humanitarian need | 5 | 2.5% |

| Head injury | 46 | 23% |

| Anticipated course | 5 | 2.5% |

One intubation was carried out by a paramedic with a HEMS doctor supervising. The rest of the intubations where carried out by a HEMS doctor with the support of the paramedic. The laryngoscopy view was recorded using the Cormack-Lehane grading scale in 187 cases, with most operators recording a grade 1 view (n=117; 62.6%), followed by a grade 2 view (n=54; 28.9%) (Krage et al, 2010). The remaining intubations were spread across grade 3 (n=14; 7.5%), grade 3b (n=1; 0.5%) and grade 4 (n=1; 0.5%). The number of attempts at intubation was also recorded and a first pass rate of 89.3% (n=167) was achieved. Second pass success accounted for 9.1% (n=17) of cases and third pass success accounted for 1.6% (n=3). No association was found between view and number of attempts (P=0.001).

Within the 187 cases, there was one episode of inability to intubate via the mouth. This patient had sustained penetrating wounds with resulting distorted anatomy. This was converted to front-of-neck access with no incision required to successfully intubate the trachea. There were six episodes of endotracheal tube cuff failure, three cases of desaturation noted and three recorded cases of the end-tidal carbon dioxide monitor on the defibrillator failing.

The 999 call to RSI time ranged from 23 minutes to 137 minutes, with a mean time of 65.6 minutes (median=61 minutes) (Figure 3). The number of cases carried out in 45 minutes or less was 27 (14.4%), with the remaining 85.6% (n=160) being performed in over 45 minutes.

Discussion

This retrospective paper has described the delivery of PHEA by a regional air ambulance service. During the period that was reviewed, the service continued to develop and respond to many pressures including the need to deliver high-quality care during a pandemic.

The successful first pass oral intubation rate of 89.3% is similar to that in other established prehospital services, as was the second pass rate (Harris and Lockey, 2011). The results demonstrated an overall success rate for intubation orally at 99.5% and a 100% success rate for delivering PHEA with an advanced airway. These success rates are similar to those reported in a systematic review conducted by Crewdson et al (2017). When considering the single case of failed oral intubation, the team progressed rapidly to gain front-of-neck access because of the severity of injuries. This was successful at establishing a patent, secure airway. No patients needed to be managed with supraglottic airway devices for transfer to hospital. Overall, this reflects positively on the delivery of PHEA by the NI HEMS team and compares well with other published levels of performance by prehospital teams (Lossius et al, 2012; Sunde et al, 2015).

The patient intubated by a paramedic was included in the results; this case occurred early on in the service's existence. This case was discussed carefully at the subsequent clinical governance meeting, with the determination that delivery of PHEA with HEMS involvement should be carried out strictly in line with the established SOP. This was important to include as it demonstrates the care taken to review cases at NI HEMS as part of ongoing development and determination to maintain the highest standards of care. Intubations are carried out by the consultant physicians with the support of the paramedics.

Paramedic practice is changing in NI and will have an impact on the delivery of RSI. Working under the umbrella of NI HEMS, the first advanced paramedics in critical care (APCC) will be taking up post imminently and will play a bigger role in RSIs as part of the NI HEMS team.

The NICE target for delivery of PHEA in trauma patients within 45 minutes of the call was used as a target for all instances of PHEA (NICE, 2016). No national guidelines or target for delivery of PHEA in medical/non-trauma patients has yet been published for comparison. The results demonstrated a mean time from 999 call to RSI of 65.6 minutes (median=61 minutes), with 14.4% carried out within the target. A recent census report on the delivery of PHEA in Great Britain demonstrated a median time of 55 minutes across 22 HEMS organisations, with 25% delivered within the 45-minute target (Turner et al, 2020). This would suggest an area for ongoing development and improvement for the service, highlighting the need to further explore NI HEMS activation times and on-scene times before RSI.

The recorded rates of laryngeal views using the Cormack-Lehane grading scale were 62.6% and 28.9% for grades I and II respectively. This is comparable to other published rates of laryngeal views for consultants performing PHEA (Chesters et al, 2014).

Limitations

This review did not look at any effect on the laryngeal view grading or intubation success rate that may have been caused by the introduction of full personal protective equipment because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The NI HEMS team operates exclusively as solely a consultant-paramedic model, which is different from most other HEMS organisations, which also operate with junior doctor trainees in prehospital emergency medical care. This may limit direct comparisons.

Conclusion

The introduction of PHEA with the start of NI HEMS team operations has been successful in delivering a safe, robust service. This is demonstrated by the 100% successful delivery of drug-assisted RSI with no need for supraglottic airways for transfer. This was supported by a robust training, SOPs and a governance structure with all instances of PHEA collected and reviewed.