Prolonged field care (PFC) is a concept born and developed in the military. It was initially developed by special forces, where extraction and evacuation may be significantly delayed because of operational pressures.

The standard military definition is:

‘Field medical care applied beyond doctrinal planning timelines to decrease patient mortality and morbidity. Prolonged field care uses limited resources and is sustained until the patient arrives at the next appropriate level of care.’

The situation in UK civilian practice is far removed from that of special forces deploying in hostile areas. However, with patients now spending longer and longer in the backs of ambulances waiting to disembark at hospitals running over capacity, it may be time to embrace the principles of PFC.

While the transition from initial care to prolonged care is along a blurred line of ongoing care, some would argue that PFC commences once a primary assessment has been completed (Smith et al, 2021), after the golden hour (Keenan and Riesberg, 2017) or at any time when onward transit of a patient to the next appropriate level of care is delayed (Remley et al, 2021) (Table 1).

| Level | Descriptor | Component features |

|---|---|---|

| Ward-based care |

|

|

| Level 1 | Enhanced care |

|

| Level 2 | Critical care |

|

| Level 3 | Critical care |

|

With ambulance crews in the UK increasingly waiting for more than an hour outside hospitals (O'Dowd, 2022), it could be argued that PFC—alternatively named austere emergency care (AEC) in civilian practice—is now within the core remit of UK ambulance clinicians.

Concept of prolonged field care

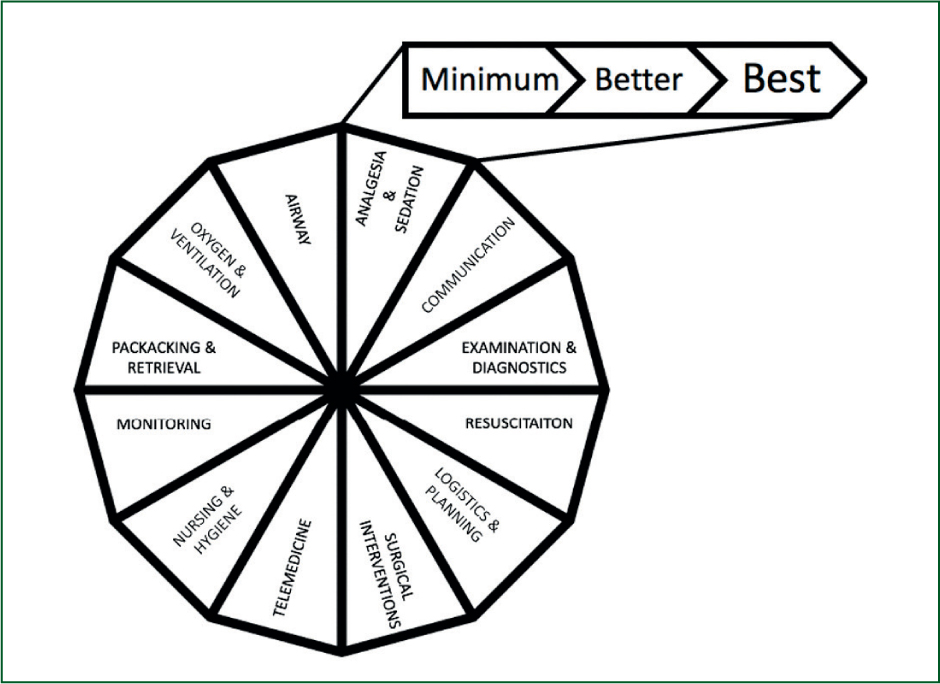

Within the overarching concept of PFC and AEC is the minimum, better, best framework, which considers the level of care you should be providing to your patient (Figure 1). The specific contents of each level can be debated and adjusted depending on operational context and best evidence.

This is often divided into 10 core capabilities (Table 2). These were developed based on the work and experiences of special forces medics; however, when this was transferred to the civilian setting, it was realised the military already focused heavily on planning, logistics and communication networks but these issues were sometimes overlooked in civilian practice (Specialised Medical Standards (SMS), 2020). Therefore, two additional capabilities were added for civilian practice (Table 3) and form the basis of AEC education (SMS, 2020).

| Monitoring | Resuscitation | Oxygenation and ventilation | Airway | Analgesia and sedation | Physical examination and diagnostics | Nursing and hygiene | Surgical interventions | Telemedicine | Packaging and retrieval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Manual sphygmo-manometer, manual pulse check | Crystalloid, tranexamic acid | Pocket mask | Manual manoeuvres, simple airway adjuncts | Non-opioids (paracetamol, ibuprofen, penthrox, etc) | Physical examination | Patient is kept clean, warm and dry, with head elevated | Needle chest decompression, needle crico-thyroidotomy, | Audio contact with senior clinician (e.g. by telephone or radio) | Understanding of the physiological stressors during transport |

| Better | Capnography, pulse oximetry, 3-lead ECG | Freeze-dried plasma | Bag-valve mask, oxygen concentrator | Supraglottic airway | Opioids (morphine), conscious/procedural sedation | Point-of-care ultrasound and blood testing | Full adoption of SHEEP VOMIT assessments and interventions | Surgical airway, thoracostomy, chest drain insertion | Audiovisual contact with senior clinician, non-live transmission of diagnostic results (e.g. ECG, ultrasound images) | Trained in critical care transport on land |

| Best | 12-lead ECG, ideally with telemetry (telemedicine) | Access to all blood products | Portable ventilator, cylinder or piped oxygen | Intubation and surgical airway, general anaesthesia | Enhanced analgesia (e.g. ketamine), regional anaesthesia, general anaesthesia | Laboratory testing | Full nursing care | Lateral canthotomy, resuscitative hysterotomy, thoracotomy | Audiovisual contact with senior clinician with live telemetry of diagnostic imaging (ECG, ultrasound, etc) | Experienced in transport of level 2 and level 3 critical care patients by land and air |

ECG: electrocardiogram

| Logistics and planning: evacuation chain, possible patient destinations, environmental challenges | Communication: within and outwith on-site team in relation to operational and clinical issues | |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Have a planned chain of care and evacuation |

Voice communication with at least one back-up system in case of failure (e.g. text messaging) |

| Better | Have practised patient evacuation with clear routes of referral |

Plans in place for voice and data communications. Ideally aligning to a PACE (primary, alternative, contingency and emergency) communication methodology |

| Best | Regular practice and current operational experience of working in the environment in question | Multiple systems, including backup systems, to allow data, video and voice communication |

HITMAN

HITMAN (head-to-toe examination, infections, tubes (and tidy), medicines, administration, nursing care) provides a core structure for PFC (O'Kelly, 2012) and is used worldwide as a prompt for providing comprehensive PFC assessments and interventions (Smith et al, 2021). Each element can be considered in terms of minimum, better, best, but all should be addressed for patients who are in your care for a prolonged period of time.

Head-to-toe examination

While a head-to-toe examination is part of a standard secondary survey during the acute prehospital phase, it is perhaps not as thorough as it might be when there are short transport times.

When managing a casualty for longer periods of time, a complete head-to-toe examination is required. This more thorough assessment may find hidden injuries and clinical signs that would not be found until the patients has been transferred to the emergency department. It is important for the remote practitioner to find all indications of injury so they can assess and manage them before they become a larger problem. All injuries and clinical signs found or suspected should be clearly documented.

Infection

Infections can start causing problems within hours of an injury. If a medical professional manages a casualty for a prolonged time, these wounds should be cleaned and any significant wound should be irrigated with at least 2 litres of potable water (Luck, 2016).

Ambulance dressings will likely require reassessment and changing to a more suitable dressing as soon as possible. A more nuanced approach to wound dressing would likely benefit patients and maximise wound healing; at a simple level, this involves using non-adherent dressings to avoid further trauma.

When the dressing is changed at a more complex level, a thoughtful choice of dressing or dressings to match the wound type is required. Wounds will likely need to be reviewed every 12 hours.

Clinicians providing enhanced care might consider debriding devitalised tissue from wounds covered with a wet-to-dry dressing or closed with sutures.

Tubes (and tidy)

In prehospital care, there is always the risk of creating a disorganised mess of wires, tubes and other equipment or devices. This is often inevitable during the acute phase of patient care, when monitoring or other intervention is prioritised over tidiness. This should, however, be remedied at the earliest opportunity.

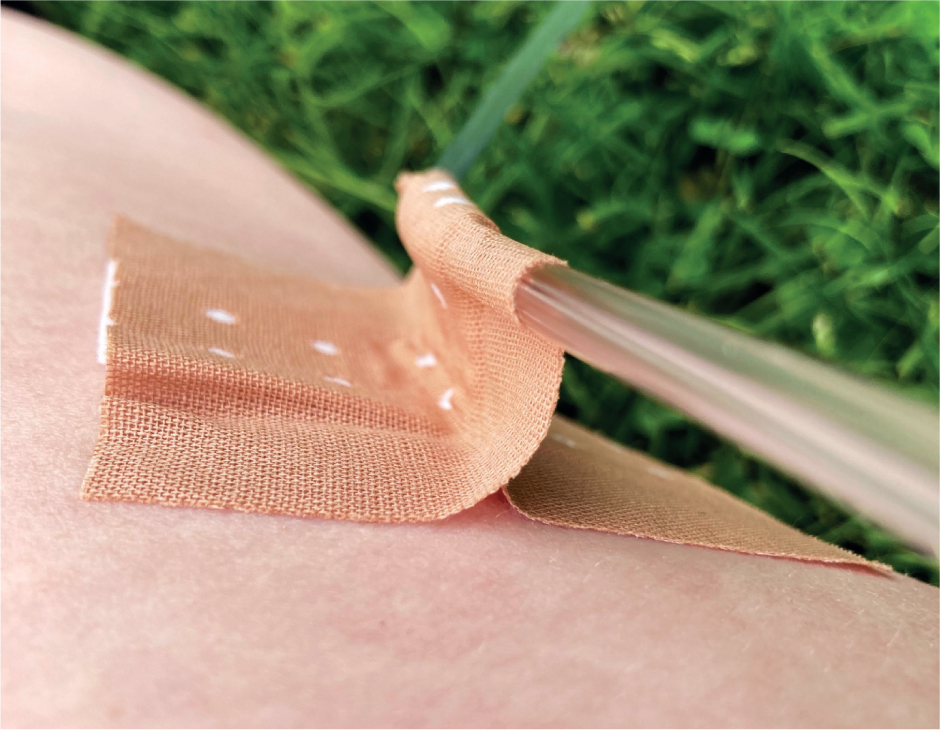

Tubes and wires should be secured. The most appropriate measure to secure these is by taping them to the patient's skin. In these cases, omental taping is far more appropriate than simply taping the tube onto the patient's skin, which risks slipping and pressure damage (Figure 2). Additionally, clingfilm can be used to secure intravenous (IV) catheters and allows the practitioner to continue visualising the IV site to monitor for problems. The clingfilm also prevents dirt and bacteria from landing on the IV site, which increases infection risk.

Endotracheal cuff pressures should be reviewed using manometry. According to Adi et al (2023), the endotracheal cuff should be inflated to 20–30 cm water. When a patient requires aeromedical evacuation at altitude, the transfer service may advise replacing the air in cuffs with sterile water. Liquids do not change volume with atmospheric pressure changes to the same extent as air, making them a more suitable choice to maintain cuff pressure.

Cannula sites should be reviewed daily using the visual infusion phlebitis (VIP) score (Bayoumi et al, 2022). Cannulas can be resited as required; they should not be re-sited purely based on the number of days or hours since they were placed, as this exposes patients to unnecessary pain and risk.

Medicines

This provides a prompt to ensure the administration of medications beyond any initial or immediate treatment has been undertaken. The practitioner will ensure that an efficacious dose of each drug has been provided.

This may include provision of long-lasting analgesia. For example, oral analgesia may be required to provide a degree of analgesia over the next 6–12 hours. Patients receiving prolonged care from an ambulance clinician may require second dosing of newly started medications. For example, a dose of cefotaxime may need to be repeated every 6–12 hours.

In addition, the patient may be due regular medication, which should not be omitted. This is especially important for drugs such as anti-epileptics or anti-parkinsonian medications, which have strict requirements around the timings of administration.

Administration

This is a prompt to ensure vital administrative tasks have been undertaken. These range from those directly related to the patient, such as completing the documentation of the assessment and treatments administered, writing referral paperwork or documenting serial vital signs.

The administration phase is also the time to replace and replenish stock. This may be possible while waiting to offload outside a hospital or awaiting retrieval at a prearranged location.

The administration phase may also involve preparation for onward transfer. A patient may require an urgent aeromedical transfer, and the prehospital clinician is waiting for the aircraft. In such cases, there may be additional tasks to facilitate a smooth transfer, such as the administration of motion sickness prophylaxis or the application of eye or ear protection.

Nursing care and SHEEP VOMIT

The acronym SHEEP VOMIT is an aide-memoire for the nursing care elements of PFC (Jarvis and O'Kelly, 2016; O'Kelly, 2018). While paramedics often refer to these tasks as nursing care, this is outdated as patient care is the responsibility of every health professional.

Skin protection

This involves consideration of skin integrity and risk from external factors, such as sunburn or insect bites. Management of skin protection would include considering the need for shade or sunscreen, protecting from biting insects using netting, applying insect repellent and covering exposed skin.

Hypo- and hyperthermia management

The minimum level of nursing care (Table 1) is to keep the patient warm and dry (SMS, 2020). While this sounds simple, maintaining normothermia in the back of an ambulance in the middle of winter is a challenge. Exposing patients to low environmental temperatures can negatively affect their clinical examination findings, worsens their experience of pain and is unpleasant (Aléx et al, 2013).

Equally, patients may risk developing classical heatstroke during a heatwave or in hotter climates (Winser et al, 2023). This is especially pertinent for those in hot, unventilated spaces, such as the back of an ambulance, for prolonged periods of time. Infants, elderly people, those with underlying conditions or polypharmacy are at increased risk, with several medications placing patients at specific increased risk (Table 4).

| Alcohol |

| Amphetamines |

| Anticholinergics |

| Antihistamines |

| Antipsychotics |

| Beta-blockers |

| Calcium-channel blockers |

| Desmopressin |

| Diuretics |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| Theophylline |

| Tricyclic antidepressants |

Elevate head

Elevating the patient's head—ideally the head of the bed—by at least 30° is beneficial for a number of reasons.

Head elevation is considered a valuable intervention for critically ill patients with head injuries (Ter Avest et al, 2021), to maximise oxygenation (Morton et al, 2022) and, possibly, in cardiac arrest (Tan et al, 2022).

In less acute patients, spontaneous ventilation when semi-recumbent (compared to supine) increases functional residual capacity and oxygenation while reducing the work of breathing (Mezidi and Guérin, 2018); it also reduces the risk of aspiration when swallowing.

There is also a psychological benefit to the patient, as it allows them to interact with the people nearby more easily. No patient should be lying supine unless absolutely clinically necessary.

Exercises

At a minimum, patients should undertake a full range of motion exercises every 8 hours. These should include the ankles, knees, hips, wrists, fingers, elbows and shoulders, as injuries allow (Ostberg et al, 2018).

Pressure relief

A pressure injury can occur in as little as 30 minutes in susceptible individuals or from extreme pressure areas, for example, when a person is lying on a sharp ridge or misplaced object.

Pressure damage can be iatrogenic; for example, a poorly sized nasopharyngeal airway causing blanching to the nare can lead to significant pressure damage to the nostril, and rigid cervical collars can cause horrendous pressure damage to the scalp, chin, neck and skin overlying the clavicle (Wang et al, 2020).

Patients should be repositioned and pressure areas checked at least every 2 hours (Ostberg et al, 2018). Any areas of non-blanching erythema should be outlined with a marker and clearly documented in the patient's notes (Ostberg et al, 2018). The patient must then be repositioned to avoid causing further pressure damage to this area, and extra padding placed in high-risk areas.

Vital signs

Regular monitoring and recording of vital signs (Ostberg et al, 2018) must be carried out, ideally using an automated monitor to maintain an up-to-date digital record and live, hands-free, physiological values (SMS, 2020).

This should also act as a prompt to start formal charting of vital signs and perhaps use the National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS2) track and trigger tool (Royal College of Physicians, 2017). Although not yet validated for prolonged field care, the tool provides a common language in relation to onward care and referral and acts as a useful marker of physiologic improvement or deterioration in a patient to whom you are providing care for a number of hours. Children will necessitate the use of the Paediatric Early Warning System (PEWS).

These tools can aid clinical decision-making about the frequency of ongoing vital sign measurements. Monitoring trends in vital signs is one of the most important skills in prolonged field care. The provider can quickly see a drop in vital signs if they have an easily viewable chart showing trends.

Oral hygiene

Oral hygiene is important for all patients but particularly so for those who are critically ill. Oral hygiene measures can be as simple as toothbrushing twice a day and can also include mouthwashes or oral gels (Ostberg et al, 2018; Zhao et al, 2020).

The bacteria that cause pneumonia are found in the mouth and can be minimised mechanically by brushing the patient's teeth twice daily.

The use of lip moisturiser is also included in oral hygiene, and is especially important for dehydrated patients or when working in hot, dry conditions (Ostberg et al, 2018).

Unconscious patients may require more regular interventions, including suctioning.

Massage

Calf massage and ankle plantarflexion and dorsiflexion are effective mechanical prophylactic interventions for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (Kumazaki et al, 2022). Conscious patients can be encouraged to complete DVT prophylaxis exercises every hour (Table 5). Unconscious patients should receive calf massage, ankle plantarflexion, and dorsiflexion every 2 hours (Ostberg et al, 2018).

| Foot pumps | The patient alternates between pointing their toes and stretching them up and back. Each position is held for a few seconds |

| Ankle circles | The patient raises both feet and traces a circle or each letter of the alphabet with their toes |

| Leg raises | Either straight leg raises or flexing alternate legs at the knee and hip, bringing the knee up to the chest |

| Thigh stretches | A straight leg raise; once the leg is brought to 90° the patient gently pulls the thigh towards their chest and holds it for 30 seconds. |

| Shoulder rolls | The patient raises their shoulders and circles them backwards and forwards five times in each direction |

Such techniques should not, however, be applied where there is a suspected or confirmed DVT already in situ (Behera et al, 2018). Compression stockings can be applied to unconscious patients (Ostberg et al, 2018).

Ins and outs

Patients need to be kept adequately hydrated and nourished. In most cases, this can be achieved through oral rehydration.

Maintenance fluid given intravenously should be an appropriate balance of electrolytes and glucose. As a sole agent, 0.9% sodium chloride is not appropriate as a maintenance fluid. Patients require the following over a 24-hour period: 25–30 ml/kg/24 hr of water, 1 mmol/kg/24 hr of potassium, sodium and chloride, and approximately 50–100 g/24 hr of glucose (this is just enough to avoid ketosis but does not meet full metabolic demands). The traditional approach to this was to prescribe ‘one salty and two sweet’: 1 litre of 0.9% saline with 20 mmol of potassium (given over 8 hours) followed by two litres of dextrose 5% with 20 mmol of potassium per litre (given as 1 litre over 8 hours).

Urine output should be measured and tracked (SMS, 2020). This should be undertaken through catheterisation but, if this isn't possible, simply keeping a record of the frequency and volume of urine passed naturally is vital. Normal urine output should be in the range of 0.5–1 ml/kg/hr (30–50 ml/hr), but aiming for the higher end of this range is preferable. In patients with suspected rhabdomyolysis, an output of 100–200 ml/hr might be more appropriate (Ostberg et al, 2018).

Clinicians must also be mindful of patients developing urinary retention during a prolonged prehospital phase. Many patients the authors see are at risk, and a number of commonly used prehospital medications can cause urinary retention (Table 6).

| Anticholinergics (atropine, antihistamines, ipratropium) |

| Benzodiazepines (midazolam, diazepam) |

| Opioids (morphine, fentanyl) |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen) |

Turn/cough/deep breath

Practitioners should remind the patient to regularly cough and take deep breaths to avoid atelectasis and consequent pneumonia. These manoeuvres should be completed 10 times every hour (Ostberg et al, 2018).

The reminder to turn or roll the patient is an intervention to prevent the development of pressure sores, as it allows practitioners to reposition a patient. In addition, it is a reminder that patients at some point may need assistance to clean themselves. This is essential for patients experiencing a code brown (an unintentional bowel movement with associated soiling) (Ostberg et al, 2018). While undertaking a bed bath in an ambulance is far from ideal, it may be required for patients waiting many hours to gain access to a hospital.

Implementing prolonged field care into an ambulance system

With the extended periods of time that UK paramedics are treating their patients in ambulances while awaiting hospital admission (O'Dowd, 2022), these PFC principles can be implemented to enhance the patient's comfort during these delays.

The use of SHEEP VOMIT can make a patient more comfortable, with a diminished likelihood of pressure sores, a better hydration status, ongoing effective therapeutic administration of regular or newly commenced medications and appropriate ongoing physiologic monitoring.

While the majority of the HITMAN and SHEEP VOMIT approach can be undertaken while working within established clinical practice guidelines and with available equipment, there are likely to be some areas of conflict between best practice in prolonged field care and policy, guidelines or available equipment.

Current ambulance equipment procurement may need to be modified so ambulances are supplied with the materials to meet patient care needs over a prolonged time frame. Items such as urinals, bedpans and materials for cleaning patients (for example toothbrushes and toothpaste) would be required additions.

In terms of policy and procedure, clinical practice guidelines need to be extended to include repeat administration of medication (e.g. second dose of antibiotics or antipyretics) and, from a training and education perspective, prehospital clinicians would benefit from gaining core nursing skills as well as developing their knowledge around issues such as the provision of maintenance fluid for patients unable to eat or drink.

The concepts of PFC are not grounded on the availability of equipment. They illustrate, however, a paradigm shift in providing high quality care to patients who should be managed in hospital, but are instead still in an ambulance, awaiting admission. While changes to policy, education and equipment provision can support PFC, these changes must be driven by frontline clinicians advocating for their patients.

Into the unknown

By definition, PFC occurs when a patient remains under a certain level of care for longer than anticipated or planned (for example in an ambulance for a number of hours). This pushes the patient and clinician into an area where traditionally there was a vacuum of guidance and best practice. By definition, prolonged field care is occurring without anticipated clinic timelines.

Traditionally, practising in this no-man's land has been discussed in terms of clinical courage (Wootton, 2011), which is the act of stepping up to or beyond the boundaries of one's guidelines and training. Its corollary, clinical caution, is where the practitioner steps back, takes no action and defers decisions and interventions to another team, individual or setting. However, light is being shone on this under-discussed area of practice, and there is now some meaningful clinical guidance in the darkness.

Leaders in the field, having drawn on their experiences in the military and through analysis of large patient cohorts, are now making progress in providing best practice guidelines for managing these patients for longer than practitioners would like to. These guidelines take the form of clinical practice guidelines available from the American military (Joint Trauma System, 2023) and in the form of the austere emergency care course (College of Remote and Offshore Medicine, 2023), which works from these guidelines and was developed by one of their authors.

While these are American guidelines developed for military use, they do provide validated guidance in the area of PFC for the generalist.

Conclusion

PFC or AEC in the civilian setting provides a mindset and collection of guiding principles for the care of a patient for a prolonged period of time. While they originate from military special forces, the core principles are directly applicable to civilian prehospital care practitioners. Further research is needed to investigate how these concepts can be applied in civilian emergency medical services.