While injury affects all ages, two demographic groups are traditionally at increased risk for unintentional trauma: children and the elderly (Xu et al, 2010). Unintentional trauma remains the leading cause of death for children in the US (Xu et al, 2010). In 2007, injuries accounted for over 35% of deaths in children aged 1-14 years (Xu et al, 2010). In 2009, over 7.6 million children under 18, and over 3.4 million persons above 65 years, were treated in hospital emergency departments (ED) for nonfatal unintentional injuries (Centre for Disease Control, National Centre for Injury Control for Prevention (CDC NCICP), 2008). Unintentional falls, specifically, were a leading cause of nonfatal injuries requiring ED visits for both age groups (CDC NCICP, 2008).

In 2003, more than 1.8 million people over age 65 were treated in ED for fall-related injuries, leading to 421 000 hospitalizations (Centre for Disease Control, National Centre for Injury Control for Prevention, 2008).

Up to 20% of these elderly persons experienced hip fractures or head injury leading to increased morbidity and mortality, along with tremendous health care costs (CDC NCICP, 2008; Roudsari et al, 2005).

Store-related traumatic injuries are often associated with modes of conveyance through inappropriate use of shopping carts, elevators, stairs, and escalators. Other aspects for increased store environment injury risk may be due to unsafe design or malfunctions of mechanical equipment. For children, hazardous behaviour and lack of parental supervision are factors that contribute to injury risks (Ridenour, 2001). For elderly persons, injuries can be a result of trip hazards due to underlying medical conditions, sedating medications, or the use of assistive devices for ambulation (Bateni and Maki, 2005).

In the US, over 1.5 million individuals use assistive walking devices which, although might increase mobility, may also get caught or impair recovery when one stumbles (Ridenour, 2001).

The purpose of this study is to identify the incidence and outcomes of retail store injuries in paediatric and elderly populations as a first step to create EMS provider curriculums and injury prevention strategies. Information regarding injury mechanism could lead to the development of safer design of store environments and prevention initiatives, including education of consumers.

Methods

The authors sought to review the literature for incidence and outcomes of EMS response to retail store injuries. English language articles were found by searching MEDLINE and PubMed (1990-May 2011) specifically for key words ‘consumer injury’, ‘store’, ‘commercial property’, ‘shopping cart’, ‘escalator’, and ‘elevator’. Articles were chosen based on EMS response and emergency department visits for age ranges younger than 18 and older than 65. References of these articles were reviewed for additional sources.

Alcohol and assault related injuries were excluded from this search. Many articles reviewed were descriptive analysis of epidemiologic data reported through the national electronic injury surveillance system (NEISS). The NEISS was established in 1972 by the US Consumer Product Safety Commission as a stratified probability sample of US hospital EDs that provides data on consumer product-related injuries (US Consumer Product Safety Commission, 1997). The NEISS obtains data from a representative probability sample of hospitals (n=98), selected from all hospitals with EDs in the US. As NEISS is a sample from these hospitals, statistical weights are applied to the data collected to generate national estimates (US Consumer Product Safety Commission, 1997). Table 1 summarizes NEISS injury publications for paediatric and elderly populations by mechanism.

| Authors | Dates of Review | Mechanism | Age studied (years) | Total number studied (estimated) | Leading injuries resulting in hospitalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wright et al | 2002–2006 | Shopping cart | <14 | 114684 | Fractures, internal organ injuries |

| O'Brien | 2003–2008 | Shopping cart | <6 | 121989 | Fractures, internal organ injuries |

| Smith et al | 1990–1992 | Shopping cart | <15 | 24 200 | Fractures |

| McGeehan et al | 1990–2002 | Escalator | <20 | 26 000 | Avulsion, amputation |

| O'Neil et al | 1991–2005 | Escalator | >65 | 39 850 | Fractures, soft tissue injuries, closed head injuries |

| Steel et al | 1990–2006 | Elevator | >65 | 44 870 | Fractures |

| O'Neil et al | 1990–2004 | Elevator | <18 | 29 030 | Closed head injuries, hand injury. |

Results

There were 22 articles collected from 5 different countries but the majority (77%) were US specific. These articles included 12 descriptive national surveillance database reviews, 3 retrospective record reviews, 4 randomized trials, a survey based study, and the remainder were case reports.

Shopping cart-related injury

In 2009, almost 19 000 children were estimated to receive treatment in ED for shopping cart injuries, with over 650 children a year requiring hospital admission (Wright et al, 2008). Between 2002–2006, the estimated overall shopping cart-related injury rates for children less than 15 years in the US was 37.8 per 100 000 population per year (PPY). Of these injured children, 51% were female (Wright et al, 2008).

The frequency of injuries was inversely proportional to age, with most injuries occurring in those less than 5 years of age (97.8 per 100 000 per person year (PPY) (Wright et al, 2008). Several studies have looked at shopping cart injuries in efforts to identify injury patterns, disposition, and prevention strategies (Smith et al, 1995; Vilke et al, 2004; Wright et al, 2008; Jensen et al, 2008; O'Brien, 2009). Injuries may occur within the store or in parking lots serving the establishment (Jensen et al, 2008). Stroller injuries in store settings are also noted in the literature with similar injury patterns (Ridenour, 2001; Vilke et al, 2004).

Risk of serious injury was increased when these were associated with stairs or escalators (O'Brien, 2009). Falls from shopping carts (>60% of cases) were reported to be the most common cause of injury, followed by entrapment or tipping over (Vilke et al, 2004; Jensen et al, 2008).

Other injury mechanisms included being struck or run over by a cart and falling off the outside of a cart (Vilke et al, 2004; Jensen et al, 2008). Children younger than 5 years account for 93% of admissions from shopping cart-related injuries with hospital diagnoses such as fractures (50%) and internal organ injuries (27%) (O'Brien, 2009).

Escalator-related injuries

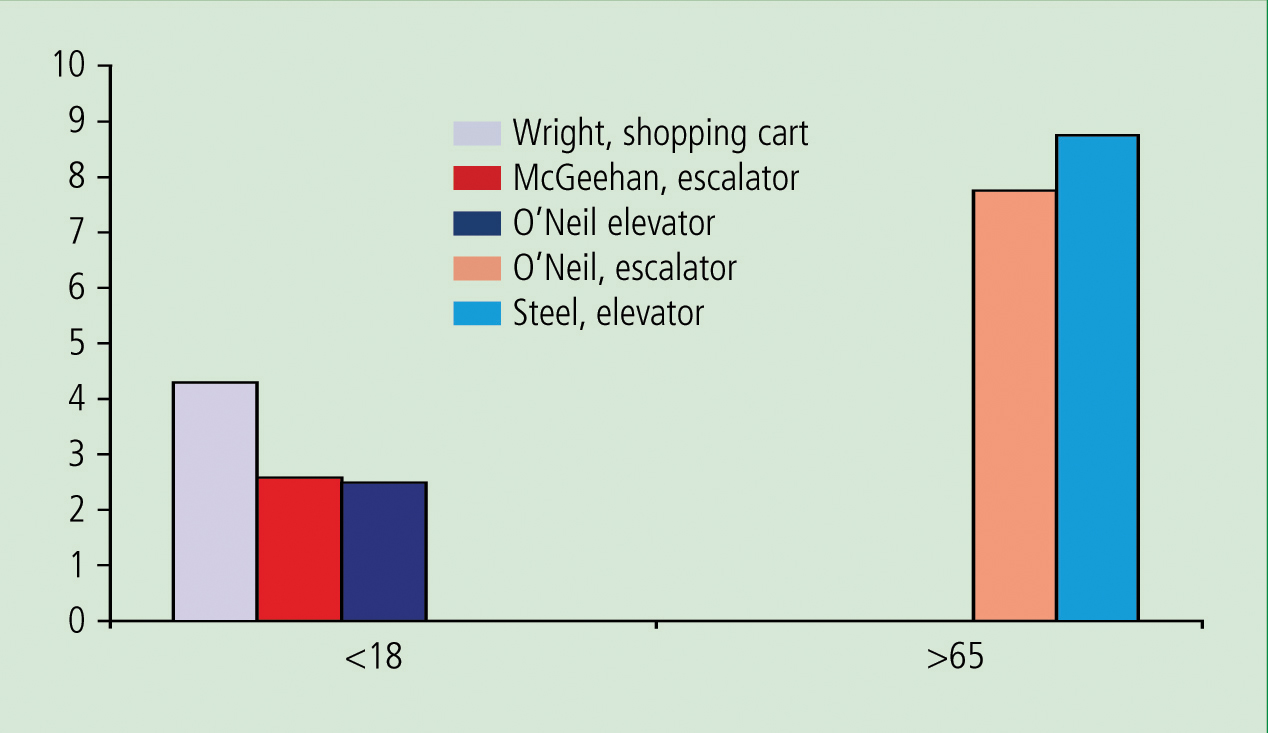

There are 35 000 escalators operating in the US with over three million persons carried per escalator per year (National Elevator Industry, Inc (EII), 2011). From 1990–2002, approximately 26 000 escalator-related injuries occurred among children less than 20 years of age for an estimated 2000 injuries occuring annually (2.6 per 100 000 PPY) (McGeehan et al, 2006). From 1991–2005, 38 500 escalator-related injuries were noted in the NEISS database among persons over 65 years with 2660 estimated per year (7.8 per 100 000 PPY) (O'Neil et al, 2008).

Over half of escalator injuries in the paediatric population occur in males with the mean age of 6.5 years. Those under 5 years of age had the highest estimated number of injuries (12 000), as well as the highest annual escalator-related injury rate (4.8 per 100 000 PPY). Falls accounted for the most common injury mechanism, in 13 000 (51.0%). Over 29% of escalator injuries were due to entrapment. The most common injury location was the leg (27.7%), while lacerations were the most common type of injury (47.4%). Amputations and avulsions were the most common admitting diagnosis and children under 5 were noted to be at higher risk for these injuries. This age group also presented with more hand injuries with most occurring as a result of entrapment (72.4%) (McGheehan et al, 2006).

The mean age of elderly persons sustaining escalator-related injuries was 80, with 73% of injuries occurring in females. Eighty-five percent of injuries were due to slips, tripping, or falls. The lower extremities (26%) and head (25%) were the most frequent injured body locations, followed by the torso (18%) and upper extremities (16%). Head injuries increased in persons over age 85, presumably due to decreased reaction time and not breaking fall with outstretched arms. Patient diagnoses on admission to hospital consisted of fractures (60%), soft tissue injuries and lacerations (20%), and closed head injuries (CHI) (20%) (O'Neil et al, 2008).

Injuries are sustained while riding the escalator when passengers were performing other tasks, not holding the hand rail, lost balance, or were struck by other riders (Platt et al, 1997). Platt et al (2007) found that 31% of children older than 4 years who were injured on escalators were using the escalator improperly or engaged in hazardous behavior such as running, playing, or sitting on the escalator. Specific footwear was implicated in some cases of severe lower extremity injuries due to entrapment (Lim et al, 2010). Strollers were implicated in 6% of all escalator-related injuries, with most due to falling out of the stroller while on the escalator (O'Neil et al, 2007).

Elevator-related injury

900 000 elevators are in operation in the US with 20 000 passengers per elevator per year (NEII, 2011). In their study, Steele et al (2010) noted that elevators are one of the safest forms of conveyance, causing only 0.015 injuries per elevator unit, when compared to 0.221 injuries per escalator unit (Steele et al, 2010). Injury and deaths still occur with significant frequency due to number of elevators and volume of use, with an average 2074 and 2640 elevator-related injuries reported respectively in paediatric and elderly persons annually (O'Neil et al, 2007; Steele et al, 2010).

The mean age of reported paediatric elevator related injuries use was 8.1 years, with over 53% of injuries occurring among boys (O'Neil et al, 2007). The overall injury rate was 2.5 injuries per 100 000 PPY. The injury rate for children aged 0–4 years was 4.2 per 100 000 PPY, and for children aged 5–19 years, the injury rate was 1.9 per 100 000 PPY (O'Neil et al, 2007). The most frequent injury mechanism resulted from an elevator door closing on a body part, with the most common reason for admission due to CHI or hand injury (O'Neil et al, 2007). Infants were noted to be at the highest risk for CHI while soft-tissue injuries were the most frequent type of injury with the upper extremity as the most injured body region (O'Neil et al, 2007).

Elevator malfunction was reported to be the cause in only a minority of incidents (Kohr, 1992). Case reports illustrate hazardous behaviours leading to significant elevator related injuries or deaths. ‘Elevator surfing’ (riding on top of or jumping between elevators) has been reported as a mechanism for crush injury or hanging (Kohr, 1992).

From 1990–2006, the total US elevator-related injury rate for adults over age 65 was almost 9 per 100 000 PPY. The mean age of the population was 79.5 years (standard deviation=8.4 years; range, 65–104 years). Injury rates increased with age (3.4 to 21.7 per 100 000 PPY) when comparing 65–69 years to those 85 years and older, with the majority (75.2%) of elevator-related injuries among women. More than half (51.4%) of the elevator related injuries in older adults were the result of a slip, trip, or fall, and almost one-third (30.6%) were the result of the elevator door closing on the person. Approximately 1440 injuries (over 3.2%) nationally were due to a walker wedged in the elevator door opening.

The most frequently injured body regions were the upper extremities and the head (26.2% and 22.5%, respectively). The remaining injured body regions were the lower extremities (17.6%), hip (11.2%), torso (10.5%), shoulder (8.6%), and other (3.8%). Hospitalizations were commonly due to hip fractures sustained as a result of falls (Steele et al, 2010).

Limitations

The majority of data in this review are from retrospective sources that must be assumed to be accurate. Limitations of using the NEISS database include possible under-reporting of injuries upon arrival to EDs, incomplete documentation, and grouping errors of injury classification. The NEISS database contains only records of injuries that are treated in EDs. This review might not be representative of injuries that do not receive medical attention or are treated in other health care facilities.

Persons injured in store environments often self triage and have several options to address their level of injury. Out-of-hospital decisions by bystanders or injured persons may result in activation of EMS, self-transport to a medical facility, or not seek medical attention at all.

Some injuries patterns may also be underestimated because documentation is reported for only one body region and one injury type per case in the NEISS data set (Centre for Disease Control, National Centre for Injury Prevention and Control, 2008). Alcohol and assault related injuries were excluded from this search. This search restriction will likely exclude a portion of injuries in this setting, due to associated hazardous behaviour increasing injury risk.

Opportunities for store-related injury prevention

Although acute management and transport of injured persons has been the traditional forte of EMS, educational interventions for preventing unintentional trauma are equally important. EMS may play a tremendous role of real-time community education interventions addressing high-risk behaviours, need for adequate parental supervision, and being community advocates to institute safe equipment designs in store settings.

Most injuries occur to children when they are unobserved and when engaging in high-risk behaviours. EMS personnel can offer education for caregivers on the risks associated with strollers on escalators or stairs, suggesting alternative access methods such as ramps or elevators.

There are many methods that can be employed to reduce injuries in commercial establishments, including restraint devices for shopping carts, tip-resistant carts, warning placards identifying trip or slippery area risks, employee monitoring of hazardous behavior, and parental/caregiver supervision. Incorporating injury prevention strategies in structural design for store environments and monitoring of potential hazardous behaviour or activities will reduce injuries. An example of injury preventive design is the use of barriers for entry to escalators or stairs which may be used to prevent access to strollers or shopping carts.

Unfortunately, safety measures are not universal and methods that are currently used have variable effectiveness. Store owners should make safety devices available to shoppers and employee encouragement increases use of safety device systems by shoppers (Smith et al, 1995).

Child restraint systems in shopping carts have limitations with currently available systems that are dependent on an active rather than passive design. This requires the shopper to initially secure the child correctly in the restraint and to remain vigilant to ensure that the child stays in the restraint (Kohr, 1992). Restraint devices may also provide a false sense of security because the child may be able to disconnect them. Unfortunately, providing information to consumers and storeowners on best safety restraints is limited.

There are no published standards for seatbelts as a safety device for strollers or shopping carts (Smith et al, 1995). Until standardized child-resistant safety restraints are developed, caregivers should maintain visual monitoring while these devices are used.

Conclusion

Retail stores are common settings responded to by paramedics for paediatric and elderly traumatic injuries. Injury patterns vary by mechanism and age group in these high-risk populations. Based on the incidence and outcomes found from this review, initial strategies for EMS curriculum development, community education and injury prevention modalities can be generated. Additional research is needed to determine the relationships among preventive injury engineering designs for modes of conveyance, consumer behaviour modification through education, and consumer-related injuries.