Essential elements of delivering high-quality prehospital care include ‘efficient call handling, robust call prioritisation and intelligent tasking of resources’ (Thurgood and Boylan, 2013: 3). This demonstrates the critical role that dispatch provides in the chain of survival for critically ill or injured patients, and where the patient's journey begins. Historically, ambulance services have used their patient response times to determine the quality of the service they have delivered. This method, however, changed based on the findings of the Ambulance Response Programme (Turner and Jacques, 2018). The new model advocates responding to the sickest patient the quickest, while providing a more appropriate response to other patients (Turner and Jacques, 2018).

In the UK, ambulance services select the software they wish to use in control centres to triage and allocate emergency calls. While other packages are available, the Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System (AMPDS) is widely used in the UK (Bohm and Kurland, 2018).

The call triage process begins when the call is answered by an Emergency Medical Dispatcher (EMD) in the control room. A strict process is dictated by the software system, which supports the identification of life-threatening emergencies early in the call process. Based entirely on the responses provided by the caller to predefined questions asked by the EMD, the call is categorised in AMPDS, and an alpha-numeric code is generated. The code identifies the clinical severity of the patient's condition and dictates the immediacy of the response required or may suggest alternative options. The categorisations range from: a life-threatening emergency to a call identified as suitable for telephone triage by a clinician; or signposting to an alternative care provider. This categorisation process supports dispatchers in allocating resources appropriately and allows for life-threatening emergencies to be identified early in the call process.

Purpose

The aim of this study was to highlight the key differences between the triage and dispatch processes of specialist resources, to establish if the findings support the use of one model over another to manage these resources, and to therefore identify best practice in call triage and the dispatch of finite, specialist resources.

The resources identified in this study and further described below, could be required where the patient's clinical condition, the environment they have been found in, or both, necessitate additional interventions that are not within the remit of the attending clinicians.

One such specialist resource, the helicopter emergency medical service (HEMS), delivers advanced clinical interventions, such as prehospital anaesthesia, thoracotomy and blood transfusions (Wilmer et al, 2015). Another resource, the Hazardous Area Response Team (HART), is mandated by the Home Office to respond to incidents involving hazardous materials, search and rescue, inland water rescue and the delivery of tactical medicine, for example during a terrorist attack (National Ambulance Resilience Unit (NARU), 2016). Additionally, a rich supply of health professionals work voluntarily to provide clinical support to ambulance clinicians, and are governed by the British Association for Immediate Care (BASICS).

These valuable resources provide niche specialist skills; however, the dispatch of these resources varies throughout the UK. HEMS, for example, can be activated independently from a computer software system due to the autonomy a clinician in dispatch retains, and as further information regarding the incident is obtained from the caller. Other methods of activation include: the specialist resource being paged, either based on the code generated by the computer triage software system; by a dispatcher who recognises the potential need for the specialist resource; or at the request of an attending ambulance clinician. Identifying the incidents where specialist responders can be best used is essential, but also challenging (Thurgood and Boylan, 2013). While these resources could greatly assist in the care of ill and injured patients, a challenge exists in identifying the subset of patients who would benefit the most (Bohm and Kurland 2018). This challenge is potentially made even greater when the decision is not supported by the focused dispatch provided to many HEMS services, and therefore falls short of recommendations made by Turner and Jacques (2018) to respond to the sickest patients the quickest.

Method

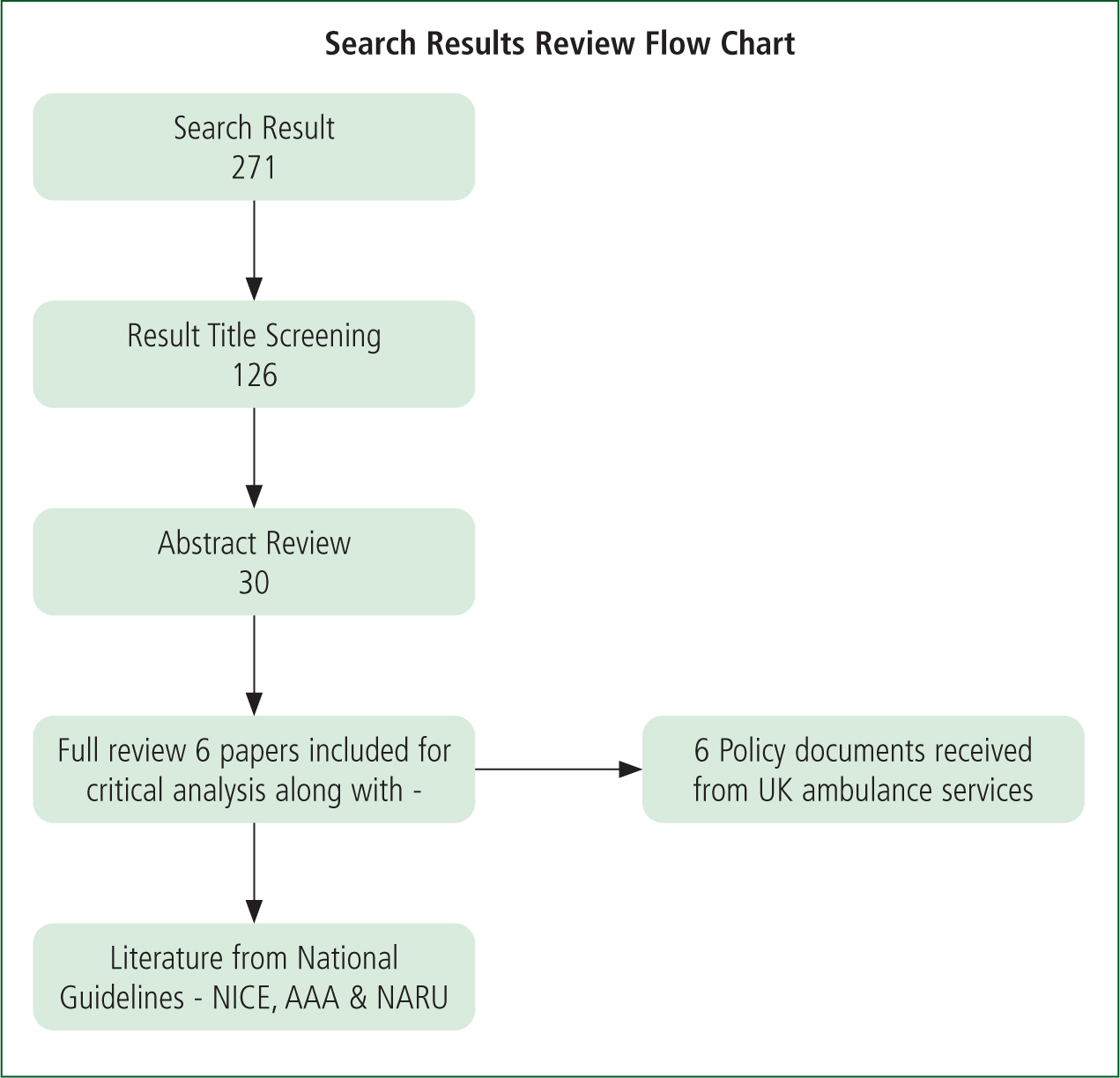

The authors undertook a literature review and analysis with the aim of establishing recommendations for best practices in improving patient outcomes through the delivery of specialist resource allocation at the point of injury. The literature review included a search of key terms in the medical databases, CINAHL Complete and Ovid MEDLINE. The key terms used were specific to roles within the ambulance service specialist dispatch. Term truncation and Boolean operators were used to assist in identifying the most appropriate literature for the study. The search was limited to the years, 2000–2020, and the literature types, ‘full text’, ‘English language’ and ‘academic journal’.

Results

The initial search produced a total of 271 records that were further screened by title to identify those most appropriate to the topic. The 126 records that met the title screening requirements were then narrowed down to 30, after having their abstracts reviewed, and a total of six papers consistent with the aims of the study were included for final review and critical analysis, along with literature from national guidelines. Figure 1 diagrammatically displays this process.

Literature review

While these sources provided some useful data, each paper had some limitations that were considered as part of this study. These findings are described below.

The Association of Air Ambulances (AAA) Best Practice Guidelines: HEMS Tasking (Chalk, 2016) provide a national document for air ambulance tasking. While air ambulance services provide a wealth of data on this topic, it should be noted that the author of the document was also involved in a research study produced by the London Air Ambulance (LAA) which addressed a clear question, comparing the efficacy of dispatch methods, through a retrospective review of data (Wilmer et al, 2015). The findings of that study reflect recommendations made in the AAA guidelines, highlighting a potential bias of the author. Additionally, as the AAA guidelines are a product of a single author, a somewhat eminence-based approach was taken.

Bohm and Kurland (2018) undertook a systematic review of the accuracy of medical dispatch. The study aim was clear, with robust and comprehensive search terms, and only examined papers that used primary data. Records selected for review were deemed appropriate based on their title. However, the authors felt that the study's timeframe of 5 years for published papers was limited, considering the paucity of studies, and that there was a risk of relevant papers being omitted. The level of evidence within this study was determined to be very low and therefore less relevant to the objectives of the authors' study. Further, due to the heterogeneity of the findings, meta-analysis was excluded.

A study by Sinclair et al (2018), examined the tasking to major trauma patients before and after the introduction of clinical dispatch. This was a retrospective review of data over a 2-year period, using national data from ambulance trauma registries. Parameters of the study were clearly set and unambiguous, which aided in reducing bias and confounders. While retrospective studies are considered a low-level source of evidence, the authors felt that there was strength in this study over Wilmer et al (2015), as the analysis of dispatch against Injury Severity Score (ISS) was outcomes-based, and calculated retrospectively. A limitation of this study was the lack of identification or analysis of the interventions at the scene.

The authors analysed a study conducted by Munro et al (2018) that reported on prospectively collated data from a pre-post study, comparing the paramedic-led dispatch process to non-clinical dispatchers (NCD) assisted by an algorithm, to guide decision-making. While the database used in this study has predefined fields for data entry, the data are entered by operational staff and there is no reported process of verifying the accuracy of the inputted data or ensuring biases are eliminated. The authors note that outcomes based on ISS were preferable, however these data were not available, nor were ambulance service data to assess the potential for missed trauma calls.

The Scottish Ambulance Service (SAS), published the Major Trauma Clinical Coordination Evaluation Report—a document that details a project supported by the Scottish government, whereby resources were introduced to assist the Scottish Ambulance Service with identifying instances of major trauma (Parker et al, 2015). This project highlighted the importance of the Trauma Desk within the Ambulance Control Centre (ACC) in Glasgow (Parker et al, 2015). The study was a retrospective review, and all data were cross-checked between the ACC and operational data. Non-conformant information was queried and corrected and missed calls were recorded; however, it is unclear how data were repaired and how missed calls were identified. The authors note that while it was evident if a team was unavailable or committed to a mission, it was not clear when a ‘clinician was busy with another call,’ and how this could be recognised (Parker et al, 2015).

The authors discovered a scarcity of literature in relation to both HART and BASICS; as such, letters and commentaries were included due to the lack of alternatives. Of particular note is a commentary made by Rawlinson (2012), stressing that the good will of volunteers should not be overshadowed by the introduction of specialist teams, and the commitment of a vast network of BASICS doctors throughout the UK continues to have a positive impact on patient outcomes. This evidence is of low-grade; however, it does display an enthusiasm for these roles, and the specialist care these clinicians deliver to patients. Greenhalgh (1999) highlights that there is both a science and an art to clinical proficiency. Therefore, dismissing these articles would lose the insights of these experienced clinicians. This is a view supported by Wieten (2018), who highlights that while expert opinion individually is categorised as low grade, when combined with external evidence and patient expectations, is nevertheless considered stronger.

Discussion

As the literature was reviewed, the authors used a thematic analysis to summarise the findings (Finlay and Ballinger, 2006). Key themes that resulted from the analysis include: over triaging, clinical and non-clinical dispatch, dispatch training, methods of identifying missions for primary dispatch and dispatching by AMPDS codes.

Over triaging

Over triaging occurs when trauma response teams are unnecessarily mobilised for patients without significant injuries (Cook et al, 2001). There are a number of concerns with over triaging such as financial impacts, increased risks of occupational injury and finite staff resources tasked less appropriately. The literature highlighted challenges involved with triaging these calls. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2016) highlights the financial impact of over triaging calls (e.g. fuel costs for aircraft, cost of additional clinical staff in dispatch centre), a view echoed by Sinclair et al (2018) and Wilmer et al (2015).

Bohm and Kurland (2018) suggest that over triaging increases the risk of occupational injury. Wilmer et al (2015) also emphasised the increased risk to responders in over triaging. Such risks may include travelling to the scene, both in relation to emergency response driving and the risk of flying, in particular the high risk associated with HEMS landings. Risks also exist to responders through the environment, as these scenes are often austere.

Another risk associated with over triaging is the inefficient use of staff resources. Over triaging deploys resources unnecessarily, rendering them unavailable for more appropriate tasking. While over triaging should be avoided where possible, Wilmer et al (2015) demonstrate the significant challenges in identifying appropriate missions for these finite resources by acknowledging that a certain degree of over triage is unavoidable and, to an extent, necessary to avoid under triage. Bohm and Kurland (2018) suggest that the system was designed to over triage to reduce the risk of missing critically ill or injured patients. NICE (2016) supports this by recognising the clinical benefit of over triage for patient safety.

While Bohm and Kurland's (2018) study suggests that by improving dispatcher accuracy, over triage could be reduced, it is important to note that many studies acknowledge that over triage is more acceptable than missing an appropriate call. Processes to reduce the over triage rate, however, did not seem to be a consideration, which may be due to the complexity of triaging calls.

Clinical and non-clinical dispatch

While the aim of dispatch is to deliver ‘the right treatment to the right patient at the right time’, challenges exist in identifying a small cohort of patients who require specialist care (Bohm and Kurland, 2018).

Clinical dispatch involves a registered clinician, such as a paramedic, monitoring and potentially interrogating incoming emergency calls to establish their suitability for specialist responders, whereas non-clinical dispatch is performed by non-clinically trained dispatchers who react to automated pager alerts, triage codes or algorithms to guide specialist dispatch decisions (Munro et al, 2018).

Wilmer et al (2014) encourage clinicians to cherry pick emergency calls where they believe a specialist resource could benefit the patient. This is achieved through a combination of predefined dispatch criteria and clinical gestalt, and is recognised as the most accurate method of dispatching this scarce commodity (Wilmer et al, 2014). While clinical dispatch is supported by many studies as the preferred method, one study casts doubt on this popular method and instead, supports the use of non-clinical dispatchers (NCD) using an algorithm to assist with triaging calls (Munro et al, 2018). The study conducted by Munro et al (2018) refutes arguments in favour of clinical dispatch, and instead highlights NCD as being as accurate as clinical dispatch, while accumulating more experience and expertise in a shorter time. The study also suggests that improving the training of EMDs/NCDs could provide a robust service of similar quality to that which is provided by a clinician (Munro et al, 2018).

Another consideration identified in the literature review involves the financial aspect of clinical dispatch. NICE (2016) raises concerns regarding the cost of clinical dispatch, while the study by Munro et al (2018) suggests a financial benefit to their model, while also providing greater service resilience.

Dispatch training

Bazyar et al (2020) promote triage as delivering the maximum benefit to the most casualties. However, deciding between patients at different incidents, often with incomplete information, creates an ethical dilemma regarding justice for each patient, and the potential moral injury for the dispatcher. This illustrates the importance of dispatch training. Coleman (1997) highlights how clinicians involved in telephone triage are supported by algorithms to guide their decisions. The literature reviewed, however, suggests that call interrogation by clinicians was unscripted and guided by the clinical acumen of the interrogator, thus exposing a risk, and questioning the ethics and governance of this system. Sinclair et al (2018) believe that the clinicians involved in delivering the care should also be involved in dispatching the team due to their intimate understanding of the care available. This view is supported by Wilmer et al (2015) who recognise that call ‘interrogation is often challenging and requires the paramedic to obtain a mental image of the incident’ which is only available with the benefit of experience. This is often not the case for an NCD as they have no first-hand experience of the prehospital environment, which suggests they are less suited to deliver this nuanced dispatch role.

Wilmer et al (2015) describe training in this area as supervised practice, while Munro et al (2018) describe a more involved process of induction, development and observation, prior to peer supervised practice, indicating a lack of uniformity in the training for this dispatch role.

Methods of identifying missions for primary dispatch

Primary dispatch occurs when the need for specialist resources is recognised from the outset of the call process, while secondary dispatch is when assistance is requested from clinicians on scene. Chalk (2016) and Wilmer et al (2015) advise that many services use three methods for identifying HEMS missions. These methods are: mechanism of injury (MOI); interrogating callers to gather more information and determine severity of injury; and request for support from a crew.

MOI for primary dispatch is a useful method for rapidly identifying potential missions. This approach, however, is generally unsupported and considered to be a weak method for identifying calls requiring specialist responders, possibly because it relies upon accurate details being provided by the caller. Interrogation of callers is an ambiguous process and one that can differ depending on the dispatcher. Interrogation is unregulated and poses a challenge in modelling and reproducing the process. Wilmer et al (2015) assert that a clinician's telephone interrogation is as accurate as that of the arriving ambulance clinician.

While a crew on the ground can request primary dispatch support, there are some challenges with this method. Waiting for a crew request delays the response of the specialist resource, possibly significantly, which undoubtedly has a negative impact on this cohort of patients (Sinclair et al, 2018). This method also relies upon the clinician at the scene identifying the need for additional specialist intervention, which has been acknowledged as unreliable (Wilmer et al, 2015).

There is no consensus regarding a standard best practice model for identifying missions requiring primary dispatch, as dispatch varies depending on geography and the skill set of the resource. Although Sinclair et al (2018) support a combination of methods to achieve appropriate dispatch decision, they continue to advocate that these decisions should be made by clinicians.

Dispatching by AMPDS codes

As discussed earlier, specialist resources can be dispatched through paging the resource. Limited evidence suggests that BASICS often respond to pager messages, based on the code generated through the call triage process. Price (2015) advises that HARTs are activated using a similar rudimentary method, which is an outdated approach for dispatching a specialist resource. The guidelines published by NICE (2016), Major trauma: service delivery, recognise the importance of triage and dispatching the correct personnel to major trauma. However, no further recommendations are made within these guidelines with respect to dispatching resources using AMPDS codes. Similarities to the NICE guidelines can be made with the resource by NARU's (2016), Service specification hazardous area response teams (HART), which identifies HARTs as responsible for coordinating interoperability capabilities in relation to high-risk incidents. This document lays out the role of the HART from an operational position; however, similarly to NICE (2016), they provide little contribution in relation to the dispatching of these resources. The lack of detail in relation to dispatch in these national documents, highlights a potential unawareness around this critical role.

Findings

This study explored the triage and dispatch of specialist resources through a literature review and thematic analysis, with the aim of establishing best practices in this complex field. The literature discourages the dispatch of specialist teams based solely on codes, generated through computer triage software systems, as these are sensitive but non-specific, could result in over triage, and therefore potentially cause inappropriate dispatches, which increases risk to responders and cost to the service.

While a common method used to identify potentially suitable missions for specialist resources is MOI, this method is considered weak and is generally unsupported. Crews can also request the dispatch of specialist resources; however, this method is also considered unreliable, and could cause significant delays, potentially leading to a negative impact on the patient. Furthermore, evidence shows that arriving crews may lack the knowledge that some specialist responders can offer, and therefore miss the opportunity to request specialist response.

The literature review confirmed that there is conflicting data regarding dispatch by a clinician versus dispatch by a non-clinician. The more widely accepted studies support clinical involvement, particularly from an ethical perspective, as clinicians can articulate the reasons for their decisions, which provides for greater oversight, accountability and governance. The literature analysed also supports clinicians further triaging calls beyond that of the computer software systems, as these specialist paramedics have the knowledge and understanding of the skills that specialist resource teams possess and can contribute to an incident.

The results of the present study indicate that a combination of MOI and caller interrogation is the strongest method of providing appropriate dispatch, when delivered by a clinician. It is recognised that clinicians provide a critical role in delivering intelligent tasking of specialist resources. Standard computer-based triage software cannot currently provide this level of specificity, nor recognise the multidisciplinary requirements.

Based on the evidence, it would be considered more appropriate to dispatch all specialist resources through a clinician, where calls can be selected and interrogated. The data from these calls can be used to compare and analyse the accuracy of the computer-generated triage code, and whether a specialist response would be of benefit to the patient and responding services. Further research in this area, particularly with the use of clinical dispatch for HART and BASICS responders, would add to the literature regarding this topic.

Furthermore, national guidelines on dispatch from NARU and NICE would support strategic decision-making for ambulance service leaders. Standardisation of titles and skill sets would support operational personnel in understanding the clinical support that is available, while standardisation of training and triage tools would support clinicians and the clinical governance concerning a role which is accepted as very challenging. Ambulance trust leaders must embrace clinical input within the emergency control room, a role which is critical for any service wishing to provide the most appropriate response to their patients. Paramedics are uniquely positioned to fulfil this role, combining operational experience and triage skills.

Limitations

There are several limitations to be noted with regards to this study. Data collected were based on the search terms selected, and after a review of titles and abstracts in the search results, the study focused on a small sample of six papers in addition to national guidelines from NICE and NARU.

Additionally, the study's focus was limited to the years 2000–2020 and the literature types ‘full text’, ‘English language’ and ‘academic’ journal.

Conclusion

The in-depth literature review and thematic analysis conducted supports the use of clinicians in dispatching specialist resources to best meet the needs of those who are critically ill or injured.

Given the unique experience of paramedics in prehospital care and patient triage, they are in a prime position to fulfil this specialist dispatch role, and further strengthen the chain of survival.