Most clinicians are familiar with the concept of the placebo effect and its common employment in medicine and healthcare. Placebo effects are usually advantageous and derive from a patient's conscious or subconscious anticipation that a medication, procedure or other therapeutic intervention will prove beneficial, as suggested by a trusted health professional (Niemi, 2009).

Positive effects can, therefore, be brought about through the use of specific words and language structure choices, causing what have been described as ‘expectation effects’ (Beecher, 1955; Massachusetts General Hospital, 2024). These result from complex psychoneurobiological actions and involve predictive processing (Blasini et al, 2017).

The placebo effect has a less well-known inverse relative or dark side, sometimes referred to as its ‘evil twin’ (Glick, 2016), which is known as the nocebo effect, derived from the Latin ‘I will harm’. Simply put, there are specific words, language structures and expressions, sometimes described as ‘nocebic terminology’ (Häuser et al, 2012), which are essentially negative verbal suggestions that can create anticipatory anxiety and induce hyperalgesia.

The psychoneurological mechanisms are similar to those underpinning the placebo effect and involve a range of neurotransmitters. However, how patients consciously or, more often, subconsciously appraise the nature and perceived meaning of comments can result in a pessimistic interpretation. This results in increased (and often avoidable) pain and anxiety, potentially together with other detrimental consequences which may affect patient outcome. De Soir (2020) claims that failure to take full account of language choice can increase the risk of patients developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). For this reason, De Soir advocates use of language to achieve ‘psychological stabilisation’.

At the very least, the use of nocebic language has negative implications for patient experience and satisfaction. The care provider's approach, specifically the presence of ‘subtle negative cues’ including non-verbal communication and attitude, is important (Benson, 1996), with a positive mental attitude adopted by the paramedic being a good foundation to work from. Responders should, therefore, be conscious of the impact of their demeanour and of specific words and language formats that should be avoided in clinical discourse (Enck et al, 2008; Kashyap and Nand Sharma, 2023).

The power of negative suggestibility is relevant to clinicians and this has been recognised for decades (Straus and von Ammon Cavanaugh, 1996; Spiegel, 1997). This has profound implications for the clinical practice of paramedics and other emergency responders, but these are often under-appreciated. If a patient is more likely to perceive pain with greater intensity when nocebic language is used (Lang et al, 2005; Faasse and Petrie, 2013), it would be, at the least, inappropriate, uncaring, unwise and, potentially, ethically questionable to proceed in such a way and may even be regarded as negligent.

The best advice might reasonably be to give thoughtful and conscious consideration to the selection of language used in a clinical encounter in the same manner that medication and treatment options are weighed up before they are implemented, with more positive and empowering language being used where indicated, to mitigate nocebic effects (Bishop et al, 2017).

Methodology

The working assumption of this pilot study was that emergency responders would display a high level of clinically appropriate communication, largely devoid of nocebic words and inappropriate language structures. In that sense, the objective was no more complex than to identify whether nocebic effect-inducing language was present. Examples of nocebic effect-inducing words are given in the discussion section.

This study is a pilot in that is was designed as a prototyping proof-of-concept exercise, forming part of the preparatory process for a possible larger-scale future study.

Five open-access examples of previously publicly, commercially televised broadcast excerpts of prehospital care were reviewed. Words and language patterns that are commonly associated with the nocebo effect were identified, tracked and recorded using a template.

Results

In each of the cases reviewed, words that are strongly associated with nocebic effects and inappropriate language syntax were commonly employed (Table 1).

| Incident | Clinician/responder | Nocebo communication by the clinician | Nocebo meaning | Appropriate alternative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stabbing victim | The lead clinician, speaking to camera and a police officer while standing at the head of the patient. | ‘I'm very concerned that the knife may have damaged the pericardium, which can be immediately life-threatening, so we need to get him to hospital quickly’(The police officer then immediately sends a radio message saying: ‘We've got a probably fatal…’) | Implies serious injury and likely fatal outcome | ‘The worst is over; you are in safe hands. We are taking you to hospital… Let your heart, your blood vessels, everything, bring themselves into a state of preserving your life. Everything is being made ready – the worst is over’ (Wright, 1990) |

| Road traffic collision | Attempting to reduce a suspected fractured tibia and fibula | ‘This is going to hurt a lot.’ (Fails to mention that pain medication has been administered) | Implies that the sensation of severe pain is imminent | ‘In a moment, you will feel the effect of the strong pain medication you have been given and this will greatly help you feel much more relaxed as we gently move the leg into a more comfortable position, so that it can start the healing process’ |

| Industrial accident | Emergency services and helicopter emergency medical services | ‘He [the patient] is not going to make it’ | Self-evident | Avoid statements of impending mortality in the patient's presence |

| Workman who appears to have struck a power line while excavating | Burns patient | ‘I'm sorry’ (before attempting to gain intravenous access); and: ‘Sorry, sharp scratch’ | Apologising before a procedure implies a lack of confidence and/or competence and suggests that a negative experience will follow, as do statements such as ‘sharp scratch’ (made worse, in this case, because the vein was missed) | ‘As we wipe the arm with some cold antiseptic solution you may feel the skin go quite numb… we are just finishing up now.’ |

| Road traffic collision | Distressed child | ‘You have lots of cuts on your face… and are very cold, so I am going to give you a blanket’ | Reinforces that the patient is injured and suggests that patient is cold | ‘In a moment [while placing blanket on the patient], you will start to feel nice and warm and comfortable, as the paramedics transfer you into their warm ambulance’ |

There were also examples of inappropriate humour and flippancy, as well as instances of patronising comments and other occurrences of poor communication. These were noted but are not included in the results as they are outside the terms of reference of this preliminary review.

The patterns of speech tended to be clinician-centric instead of demonstrating inclusivity, with phrases such as ‘I am going to do this’ rather than being patient-centred.

In general, the overall impression was of a rather directive approach, somewhat deficient in sensitivity and with seemingly no awareness of the concept of nocebic communication.

Discussion

Patients who sustain serious trauma or acute illness often develop a modified state of awareness (Bierman, 1989), amplified because of anxiety and fear—conditions that are known to increase susceptibility to suggestion (Dabney, 1999).

This increased or ‘heightened state of perception’ (Brown, 2011) has been linked to the type of focused attention that has been noted to occur during hypnosis (Woody and Sadler, 2008). Retreating into this ‘trance equivalent state’, which does not necessarily involve any objective loss of consciousness, may be a reaction with an evolutionary basis (Jacobs, 1991) and possibly acts as something of a refuge from the predicament.

The circumstances of a traumatic incident are usually unexpected, confusing and unpleasant. All of these factors increase patient susceptibility to literal interpretation (Erickson, 1964a; 1964b). Provider directions, comments or instructions can, therefore, be over-, erroneously or pessimistically interpreted (Erickson and Haley, 1967). For these reasons, it is important for providers to be aware that negative words, language structures and suggestions can engender a nocebic effect. This can result in a patient experiencing greater pain and anxiety (Benedetti et al, 2003) or worse clinical outcomes than would have been the case had adequate care and attention to communication been exercised by the provider.

Examples of sabotage words that are typically defined as nocebic, and which were specifically searched out in this study are:

- Needle

- Pain (rather than saying discomfort)

- Painful

- Hurts

- Sharp

- Scratch

- Sharp prick

- Sorry

- Try (implying failure).

The type, language formats, phrases, directions and syntax that should be avoided include:

- ‘Keep still’

- ‘Don't move, or you will make things more difficult’

- ‘I don't want to hurt you’

- ‘Your veins are really poor/difficult’

- ‘I'm not sure this is going to be successful’

- ‘This is going to hurt’

- ‘Sorry’

- ‘Is your pain medicine working? Oh, not yet then?’

- ‘You feel very cold’

- ‘I don't think he's going to make it’

- ‘You have bad burns to your face and your airway might close up’

- Within earshot (immediately by the patient's head): ‘I'm very concerned that the knife may have damaged the pericardium, which can be immediately life threatening, so we need to get him to hospital quickly.’

Beyond critical or serious trauma cases and medical emergencies, which are rare in paramedic practice as the workload takes on an ever more urgent care complexion (Newton, 2012; Brewis and Godfrey, 2019), there are many opportunities in more routine patient care encounters to avoid nocebic language. Allaying patients' concerns and modifying language in a manner that can shape a patient's subjective experience is good practice and enhances the quality of care. Such occasions include the placement of a blood pressure cuff around an arm, replacing words such as tight, crush or strangle with ‘the blood pressure cuff will start to inflate gently/snugly round your arm providing useful information’.

Equally, when inserting an intravenous cannula, suggesting that ‘the arm’ (thereby distancing the patient from ‘their arm’) may respond to the ‘cold antiseptic by feeling numb or heavy’, while also directing the patient's attention (by perhaps asking them to wiggle their toes, or look upwards at a fixed point), can be helpful in reducing the patient's awareness of their arm. In this way, modifying ‘procedural disclosure’ can engender positive effects (Krauss, 2015).

These effects have been tested using a multicentre randomised trial confirming the value of hypnoidal language (Fusco et al, 2020). As a result of such research and the increasing number of clinical studies demonstrating the nocebo effect, and citing an approach that can be applied in mitigation, a consensus is gradually emerging regarding the need to publish guidance. An international expert group (Evers et al, 2018) has said that health professionals should be trained to maximise placebo effects and minimise nocebo effects.

Mechanisms

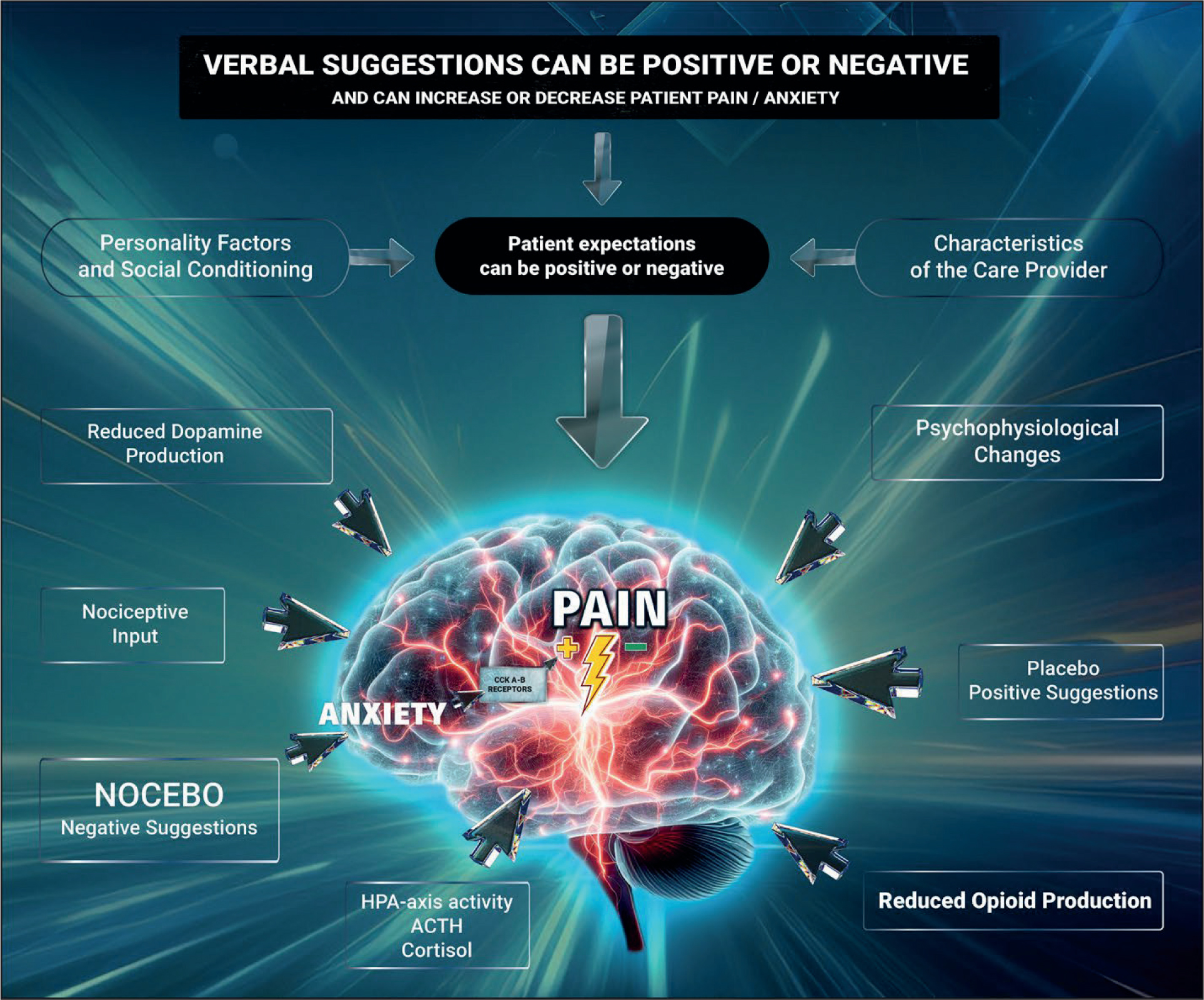

The mechanisms through which nocebic language is translated into psychological effects are complex and involve multiple pathways, both neurological and neuroendocrine. Various neurotransmitters, including cholecystokinin, dopamine and endogenous opioids (Arrow et al, 2022), have been identified. These systems have been described by researchers (Benedetti, 2014a; 2014b) and involve multiple interactions that may be expressed differently by individual patients (Benedetti, 2014a; Corsi et al, 2016). These mechanisms can involve conditioned responses and social learning (Vögtle et al, 2013), and illustrate how the power of thought is translated into psychophysiological effects.

When activated, this neurological process can promote analgesic effects and reduce anxiety through the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (Benedetti et al, 2006). The cholecystokinin system is also significantly involved, as is the opioid system (Benson, 1997). The anterior cingulate cortex (Freeman et al, 2015), a structure frequently implicated in hypnotic effects, has also been identified as potentially playing an important role.

Blasini et al (2017) developed a diagrammatic model to show the process visually; Figure 1 shows a simplified version.

Evidence

In this preparatory review, previously televised excerpts were chosen largely because they are readily available. Increasingly, ambulance services and other emergency care organisations tend to welcome media coverage to emphasise their role and contribution to the community. As such, large amounts of previously transmitted open-access digital material is available for review.

This is something of a paradox because the importance of a language has widely and long been recognised in literature by researchers such as Benedetti (2002). There has also been some interest among the prehospital care research community, for example, Cheek (1969) and Dick (2010) in the United States; however, it has received less attention in the UK.

If the standard of nocebic effect-inducing communication discovered in this study is representative of the routine discourse in clinician–patient interaction, it could be regarded as a largely unrecognised patient safety concern. This begs the question as to what extent the prevalence of nocebic communication has been addressed in the UK and abroad, and what strategies might be available to improve provider performance in this area.

Strategies for improvement

Some methodologies already exist to counteract potentially harmful communication. Cyna, a senior Australian anaesthetist, has written extensively about how clinicians can avoid nocebic effect-inducing communication, particularly in children (Cyna, 2020), and has also worked on a textbook on the subject (Cyna et al, 2010). In Hungary, Varga has reported on a successful approach that trains health workers in positive suggestion techniques (Varga, 2013) while, in the United States, Bierman, an emergency medicine consultant, has introduced a similar approach, including the use of hypnotic inductions (Bierman, 1989). The United States' National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians (NAEMT) has developed a short course, ‘Psychological trauma in EMS patients’, which – while stopping short of training in the use of hypnoidal language to avoid nocebic effect-inducing language – encourages paramedics to adopt an approach that, in some ways, parallels the aforementioned techniques, emphasising social support to assist the patient through a time of crisis, seeking to reduce ‘fear, stress and pain’ (NAEMT, 2024).

Jacobs, an author with a paramedic background, has gone somewhat further, advocating for the use of hypnotic communication in emergency care, especially in paramedic practice, and recently published a book with a co-author, Duffee, who is a practising paramedic (Jacobs and Duffee, 2023). Duffee (2023) also recently produced an article that helps to raise awareness of communication failures in paramedic practice and of existing opportunities to improve patient care.

Acosta and Prager (2014) published a short text with the general public in mind, essentially providing advice on verbal first aid. Lang and Laser (2009), noted researchers in this area, developed a short programme geared to the needs of radiographers and nurses to assist them in applying clinically helpful ‘comfort talk’ language structures in primarily radiological hospital settings.

These enterprising developments appear to represent positive progress and have the significant advantage that they do not require the much more extensive training needed to function as a hypnotist. Full hypnosis training and accreditation is a level of skill more difficult to acquire but, nonetheless, well established in the NHS within the medical and dental professions. For more than 70 years, organisations such as the British Society of Clinical and Academic Hypnosis (BSCAH) has offered training, education and support primarily for the medical profession (British Medical Journal, 1957), but more recently for allied health professionals too (BSCAH, 2023).

At a College of Paramedics conference, the use of emergency hypnoidal communication was proposed as a possible means of aiding paramedics to improve their performance in this area (Newton et al, 2023). A Position Statement has been developed covering the potential use of hypnoidal language and hypnosis by paramedics. This is under consideration by the College for possible future publication. At least one university that offers a paramedic degree programme (Oxford Brookes) has expressed interest in these developments. It is therefore likely that training may be forthcoming soon for paramedics.

It must be recognised that while hypnosis and hypnotic techniques have a long history, this is a new area for paramedic practice. Research into the use of emergency hypnoidal communication, designed to reduce the use of nocebic language and increase the practice of employing positive suggestion by paramedics is therefore limited.

Nonetheless, one study stands out as of particular interest. In the mid-1970s, Wright (1990), a psychiatrist, trained a group of paramedics in the use of hypnoidal techniques. The approach employed a short script, which was used by the paramedics when attending to patients experiencing major trauma (as advocated in Table 1). While the text recommended in Table 1 and below is not an exact replica (but rather an approximation) of the passage used by Wright, it is indicative of the language that was employed with seriously injured patients:

‘The worst is over; you are in safe hands. We are taking you to hospital…. Let your heart, your blood vessels, everything, bring themselves into a state of preserving your life. Everything is being made ready, the worst is over.’

The word choice was carefully crafted, and paramedics were encouraged to remove patients rapidly to the ambulance and avoid extraneous communication. The results were reported by Wright at an American Society for Clinical Hypnosis conference in 1977 but were only published later (Wright, 1990) as part of a wider text of hypnotic suggestions and metaphors.

Although it is an old study that would benefit from replication, the findings were positive, with a reported higher survivability and shorter hospital stays for the intervention group (Wright, 1990). If validated, it would suggest that paramedics equipped with the necessary training could expect to achieve superior patient care and may also be able to reinforce a patient's psychophysiological survival mechanisms.

Issues for practice, research and discussion

The neuropsychological processes that underpin nocebic effects have been elucidated by research efforts, particularly during the last two decades, but the work on this is not yet complete (Faasse and Petrie, 2013).

Questions remain regarding what sort of provider characteristics and attributes are well suited to delivering effective hypnoidal communication that eschews nocebic language and emphasises positive suggestion. These are likely to be correlated with provider personality characteristics that emphasise sincerity and avoid an overbearing approach. Demonstrating empathy has also been found to enhance and reassure, and reduce the nocebo effect (Meijers et al, 2022).

Care providers' appearance (dress and grooming, etc) (Kanzler and Gorsulowsky, 2002; Willis and Mellor, 2014), perceived trustworthiness (Ashton-James and Nicholas, 2016), believability (Jacobs, 1991), competency (Korsh and Negrete, 1972), and other interpersonal factors (Duffee, 2002), are also relevant. It is therefore likely that, in this aspect, the debate forms part of a well-established dialogue on clinical interpersonal communication, which has long and frequently been recognised as an area of weakness in medical and healthcare training and performance (Hall et al, 1988; American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2014; Campbell et al, 2018; SQW, 2021).

Nocebic effect-inducing communication is a much broader issue affecting a spectrum of settings in which consultations and clinical interactions take place. Opportunities for improvement in this area are correspondingly extensive.

Limitations

This project had a small sample and was designed as a prototyping proof-of-concept exercise, ahead of a potential larger study in the future. The excerpts selected for viewing were historical and may not reflect current practice.

Conclusion

Based on a small sample of recorded historic emergency responses involving seriously injured patients and, notwithstanding the other limitations to this pilot review, it would seem reasonable to conclude that nocebic communication is likely to be a common phenomenon in prehospital and out-of-hospital care practice.

It is clear that detrimental, nocebic effects are shaped by the use of specific words, phrases and other linguistic syntax, and have a well-recognised ability to worsen patient experience and increase discomfort. It is also possible that longer-term patient outcomes could be negatively influenced. Considering the language used by paramedics and other practitioners, and guarding against the nocebo effect, might prevent the increased risk of PTSD or other psychological sequelae.

Nocebic language can reasonably be regarded as a patient safety issue that can be easily avoided. It is a subject that invites further research efforts, coupled with the employment of strategies to obviate and ameliorate potentially harmful consequences. Exploring and encouraging the use of positive suggestion by paramedics and other emergency care providers therefore offers a path towards improved patient care.

Beyond these, further opportunities can be envisaged, including providing paramedics with comprehensive postgraduate training and education in the use of more advanced hypnotic techniques. Perhaps the era of the hypno-paramedic may become a reality in the near future.

Key Points

- Word choice should be considered alongside medication or treatment choices

- Some words can engender negative psycho-physiological responses, increasing pain and anxiety and possibly worsening patient outcome

- Some words can have positive psycho-physiological results, including reducing pain and anxiety and possibly improving patient outcome

- Potentially harmful words are termed nocebic—from the Latin for ‘I do harm’—and should be avoided wherever possible

- Adopting positive word choices—using hypnoidal communication—can improve patient care

CPD Reflection Questions

- Review the failure words and nocebic phrases in this paper and ask yourself whether or not you use them in practice.

- Write down 5–10 alternatives to nocebic words. How could you work consciously to substitute these words and phrases in your practice and encourage your colleagues to do the same?

- After reading this paper, reflect upon (by means of listing) three of the basic communication skills that you do well and also a further three that you would like to improve upon.