A terrorist attack (TA) is a violent threat designed to intimidate the public, creating feelings of fear and vulnerability (HM Government, 2000). In the past decade, North America and Europe have seen a growing number of violent TAs associated with racial or ethnically motivated extremism targeting police and civilians (Global Terrorism Trends and Analysis Centre, 2021). These attacks present unique challenges to the emergency services, from managing an ongoing threat to navigating the numbers and types of casualties (Wesemann et al, 2022).

Global learning from previous TAs has influenced the evolution of organisational preparedness and operational procedures (Gates et al, 2014; Rathore, 2016; Kerslake, 2019; Lucraft, 2019). This includes the introduction of the Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Programme (JESIP) and hazardous area response teams (HARTs) (Price, 2016; HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services, 2024). These changes are intended to enhance the capabilities of ambulance services to provide life-saving treatment at the site of a TA. However, there is criticism that this learning and development fall short regarding the psychological impact of these events on first responders (Thompson et al, 2014; Wilson, 2015; Moran et al, 2017).

Responders are ‘any individual, regardless of organisation, role or rank, who responds to or supports the response to an incident’ (JESIP, 2021: 6). Man-made disasters, such as a TA, have a more significant psychological impact on responders than natural disasters (Norris et al, 2002; Bromet et al, 2017). Responders have been found to develop some of the highest rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), second to the survivors, following an act of terrorism (Benedek et al 2007; Berger et al, 2012).

PTSD is defined as a mental health condition that is caused by exposure to a traumatic event. Unlike anxiety or stress, symptoms will continue for a month after the event, interfere with daily life and cause extreme distress (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2021).

The impact goes beyond PTSD; recent studies have found responders develop sleep disorders, cognitive issues, emotional and physical health problems as well as substance and alcohol misuse (Thompson et al, 2014; Litcher-Kelly et al, 2014; Aubert, 2017; Danker-Hopfe et al, 2017). It is becoming apparent that the biggest threat from a TA to responders is to their psychological wellbeing not from the physical hazards at the incident (Thompson et al, 2014; Wilson, 2015).

The prevalence of PTSD in first responders varies between occupational groups, with high rates found among ambulance personnel (Berger et al, 2012); Wilson, 2015; Wesemann, 2022). The cause of this is hypothesised to be variation in duties or training (DiMaggio and Galea, 2006). Recent studies have found that paramedics reported shortcomings in preparations to manage the personal stressors associated with TAs (Hugelius et al, 2021). Paramedics felt unprepared as emergency practitioners to attend a TA (Day et al, 2021). Furthermore, paramedics reported expectations to continue as normal after a TA (Moran et al, 2017).

While these issues profoundly impact individuals, they also affect organisations with increased sick leave, retention issues and early retirement (Berger et al, 2012). Despite this, the psychological impact of these events on responders is often poorly incorporated into operational policy (Moran et al, 2017). The wider literature calls for consideration of this ‘hidden risk’ when planning for future responses with improved individual emergency preparedness (Thompson et al, 2014; Wilson, 2015; Moran et al, 2017; Day et al, 2021; Skryabina et al, 2021).

The author (JT) acknowledges that these events are rare and few paramedics may be exposed to them during their careers. However, the role of the ambulance service within the emergency response to a TA is increasing. New roles such as HART and other specialist assets such as tactical response units within the London Ambulance Service require paramedics to respond to a marauding terror attack from within the attack site (National Ambulance Resilience Unit (NARU), 2024).

Much of our understanding of how TAs impact first responders psychologically comes from studies focused on police and firefighters (Berger et al, 2012; Wilson, 2015; Wesemann et al, 2022). To adequately prepare paramedics and manage the psychological burden, first this burden needs to be understood (Wilson, 2015).

Aims

This literature review aims to critically analyse contemporary research that explores the psychological impact of real-life TAs on paramedics within the prehospital environment to answer the question: ‘How does responding to a terror attack impact the mental wellbeing of paramedics?’

Methods

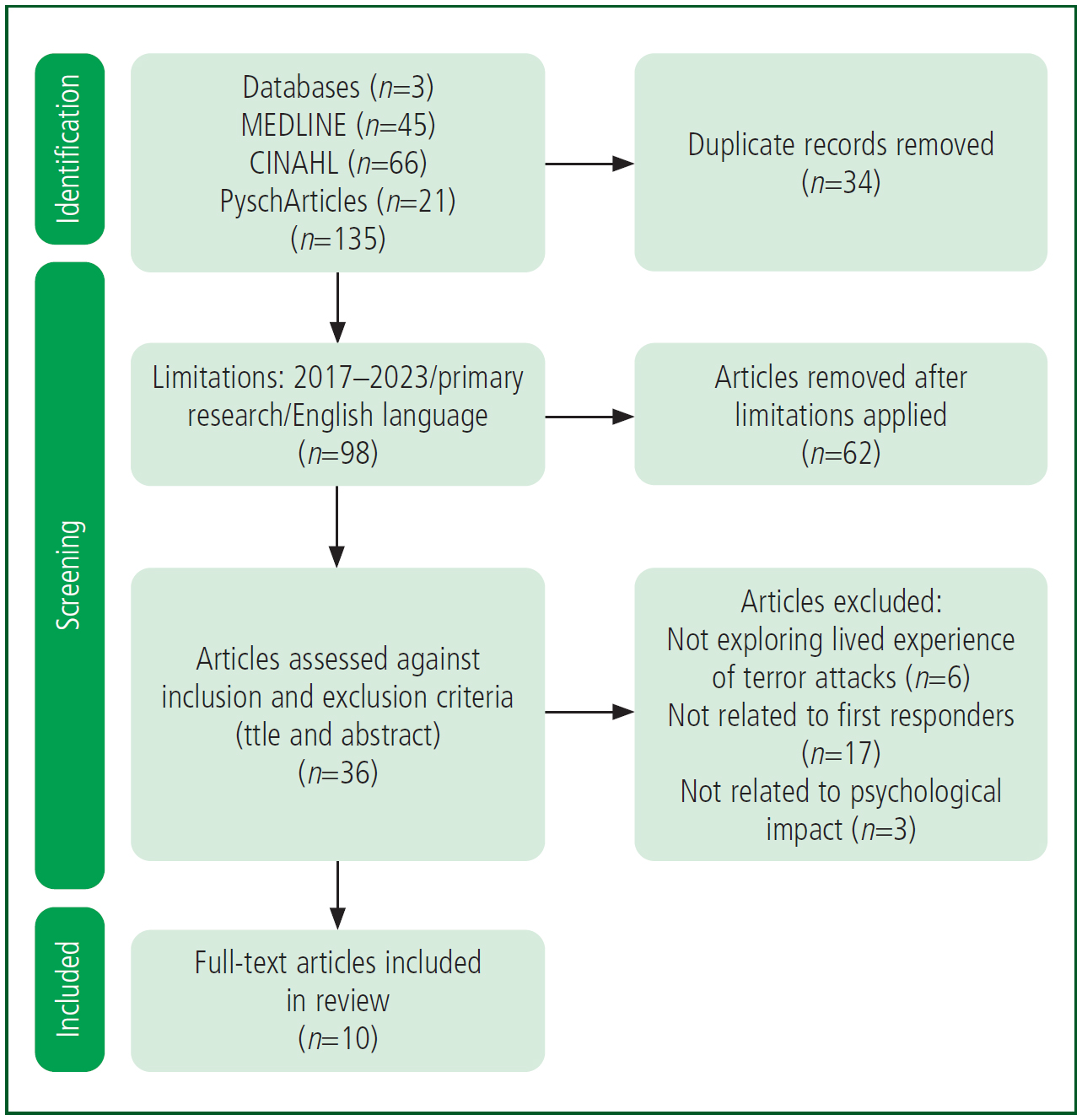

A narrative literature review was carried out using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) strategy (PRISMA, 2020).

The CINAHL, MEDLINE and PsycArticles databases were searched up to 6 September 2023 because of time restraints and over the previous 5 years to identify recent research and as there was a single researcher (JT). Boolean searches were conducted using the key terms: (“terror attack” OR “Terrorist Attacks”) AND (“paramedic*” OR “healthcare” OR “First Responder” OR “emergency medical services” OR “EMT”) AND (“PTSD” OR “wellbeing” OR “anxiety” OR “depression” OR ‘”mental health” OR “psychological impact”). Search results were limited to peer-reviewed journals and articles published within the past 5 years written in the English language. The titles and abstracts were assessed against inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1).

The critical appraisal of the literature was undertaken using different tools corresponding to the methodology of each paper (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP), 2018a; 2018b; Joanna Briggs Institute; 2020).

Simple thematic analysis was used to synthesise the data and summarise the relevant findings (Table 1) (Aveyard, 2019; Coughlan and Cronin, 2021). Synthesis was undertaken by the principal researcher, which created limitations to this review. Another limitation is that the author's personal experience of attending a TA while employed with an inner-city ambulance trust could lead to synthesising themes that fit with the author's own experiences creating a research bias (Aveyard, 2019). The thematic analysis was discussed with a third party to minimise these limitations.

| Author | Aim | Methodology | Participants and time after incident | Findings/recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith and Burkle (2019) | Explore paramedic and EMT reflections of long-term impact of responding to 9/11 | Qualitative |

18 paramedics |

Psychological effects include survivors’ guilt, recollections, anxiety, depression and PTSD. |

| De Stefano et al (2018) | Estimate the effect of direct participation in the rescue on PTSD symptoms |

Quantitative |

91 rescue workers |

Participants had 28% more PTSD symptoms than non-participants. Female sex and basic training were associated with increased PTSD symptoms |

| Vandentorren et al (2018) | Assess mental health impact and access to psychological medical care of people exposed to attack (civilians and FRs) | Quantitative |

232 First Responders (19% professional medical rescue workers, 26% firefighters, 24% police officers, 31% volunteers) |

3% rescue workers diagnosed with PTSD; 18% civilians diagnosed with PTSD |

| Wesemann et al (2018) | To assess sex- and occupation-specific effects of a terrorist attack, particularly on emergency responders | Quantitative (pilot study) |

16 firefighters |

Difference between occupational groups may be attributed to difference in tasks that responders perform during acute incidents |

| Smith et al (2019a) | Explore preferred self-care practices of paramedics and EMTs | Qualitative |

18 paramedics |

Explored useful physical and psychological self-care practices adopted by paramedics and EMTs who responded to 9/11 |

| Motreff et al (2020) | Measure psychological impact on FRs using PTSD and partial PTSD symptoms |

Quantitative |

229 health professionals |

4.4% of health professionals and 3.4% of firefighters had PTSD |

| Bentz et al (2021) | Describe mental health impact among hospital staff |

Mixed-methods |

804 participants |

Despite a support system being set up by Nice hospitals administrations, few staff sought support, especially those in the professional exposure group who were experiencing the most symptoms |

| Motreff et al, (2022) | Identify factors associated with receiving immediate support, post-immediate support and engagement in mental healthcare | Quantitative |

226 health professionals |

10% health professionals had PTSD |

| Skryabina et al (2021) | Understand more about FRs’ perceptions of responding to a terrorist incident, with the aim of improving preparedness | Qualitative |

7 medical consultants |

Recommended future research on how best to support/prepare trauma-exposed staff |

EMT: emergency medical technician; FR: first responder; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder

Results

Nine articles were included in this review, which explored terror attacks in London and Manchester in 2017 (Skryabina et al, 2021), Paris in 2015 (De Stefano et al, 2018; Vandentorren et al, 2018, Motreff et al, 2020; 2022), Nice in 2016 (Bentz et al, 2021), Berlin in 2016 (Wesemann et al, 2018) and New York in 2001 (Smith and Burkle, 2019; Smith et al, 2019a). While most explored the psychological impact 2-14 months after the attack, two explored the impact 5-15 years later.

Thematic analysis drew out multiple themes; this review focuses on two of them: level of exposure; and level of preparedness.

Level of exposure

Six papers explored responders’ degree of exposure within a TA with prevalence of PTSD and other psychopathology (De Stefano et al, 2018; Vandentorren et al, 2018; Motreff et al, 2020; Bentz et al, 2021; Skryabina et al, 2021; Motreff et al, 2022).

Two papers highlighted that first responders who had directly participated in rescuing victims from the attack site had higher prevalence of PTSD symptoms compared to those who did ‘not participate’ and treated victims away from the attack site (De Stefano et al, 2018; Bentz et al, 2021). In addition, the closer responders were to the threat within the site of a terror attack, the higher their prevalence of PTSD (Vandentorren et al, 2018; Motreff et al, 2021). Exposure to unsecured crime scenes and witnessing violence also increased the risk of PTSD (Motreff et al, 2022).

However, the degree of exposure did not have an impact on symptoms of hypervigilance and re-experiencing the event (De Stefano et al, 2018).

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were equally as high in first responders who did not participate at the attack site as in those who treated victims within hospitals (Bentz et al, 2021).

Further emotions such as unmanageable guilt and fear were found in responders who treated victims away from the site of the attack (Skryabina et al, 2021).

Level of preparedness

All nine papers addressed how responders’ degree of preparation directly impacted the development of PTSD and other psychopathological outcomes.

Two quantitative studies addressed the association of ‘previous training’ (Motreff et al, 2020) and ‘unfamiliar tasks’ or ‘working outside scope of practice’ (Bentz et al, 2021) with the prevalence of PTSD. Being confronted with an unfamiliar task was positively associated with a higher risk of developing PTSD, although this finding lacked statistical significance (Bentz et al, 2021). An absence of training on the psychological consequences of responding to a TA correlated with the development of PTSD (Motreff et al, 2020).

The qualitative papers within this review drew out themes from responders of ‘preparedness’ (Skryabina et al, 2021), ‘failings’ (Smith and Burkle, 2019) and ‘being ill-equipped’ (Smith et al, 2019a) to respond and recover from a TA. Overall, the findings suggest that the amount of psychological preparation, education and training responders receive before attending a TA directly affects their psychological wellbeing.

Discussion

It is known that exposure to TAs increases the risk to responders’ mental wellbeing and places them at greater risk of PTSD (Berger et al, 2012; Williamson et al, 2018; Smith et al, 2019b). However, the findings imply that paramedics’ level of exposure within attack sites poses varying risk to mental wellbeing.

Within the UK, the operational response to a TA is controlled with zones: hot; warm; and cold (JESIP, 2021; NARU, 2024). The hot zone is an area of continuing imminent threat, the warm zone contains moderate risk and the cold zone is a safe working area away from the threat (NARU, 2024).

When responding to a TA in the UK, paramedics typically work within the cold zone, and specialist-trained paramedics such as those in HART and tactical response units enter the warm zone to triage and extricate patients (NARU, 2024). These zones are established from an ongoing assessment of the risk posed to responders by the attack methodology and environmental hazards (JESIP, 2021). The findings suggest that paramedics who work in the warm zones of a terror attack are at greater risk of developing PTSD and other psychopathology (De Stefano et al, 2018; Vandentorren et al, 2018; Motreff et al, 2020; 2022; Bentz et al, 2021; Skryabina et al, 2021).

Ambulance services’ response to TAs is evolving; incident commanders must now accept some level of risk and rapidly deploy responders based on local trust policy and attack methodology (NARU, 2024). An inner-city trust now permits all paramedics to work in the warm zone of a marauding terror attack alongside specialist paramedics (Emmerson, 2020). These adaptations have arisen following the inquest into the London Bridge attacks in 2017, as paramedics were delayed in providing life-saving treatment to patients as they could not enter the warm zone (Lucraft, 2019). The ambulance service was criticised for being ‘overly cautious’ of risk and was requested to find a better balance between treatment and safety (Lucraft, 2019). Similar conclusions were drawn from the Manchester arena inquiry as commanders were criticised for not sending all paramedics into the warm zone of the incident (Saunders, 2022). Permission to move into a warm zone of a TA is at the discretion of the incident commanders and depends on personal protective equipment and attack methodology (NARU, 2024).

While the physical risk may be controlled, organisations must understand the additional dangers to mental wellbeing that this policy change may present to paramedics (Thompson et al, 2014). It is essential to consider how this risk could be further managed.

In addition, findings imply that those not directly exposed developed symptoms of psychopathology (De Stefano et al, 2018; Skryabina et al, 2021). A small amount of qualitative research found responders expressed guilt over not being there to support their colleagues at the attack site (Skryabina et al, 2021). This implies paramedics who are not dispatched to a TA, such as those who wait at a rendezvous point, are also at risk of developing adverse psychological outcomes so should be included in any post-incident screening and support.

Alongside the level of exposure, the findings suggest that the amount of psychological preparation, education and training affects responders’ psychological wellbeing after attending a TA. Wider studies have shown that medical emergency preparedness for TAs is low (Gulland, 2017; Chauhan et al, 2018). The findings suggest that a lack of education on the psychological risk of attending traumatic events puts responders at a greater risk of developing PTSD (Skryabina et al, 2021; Motreff et al, 2022). Furthermore, the lack of control experienced by responders to TAs correlates with their development of PTSD (Raz et al, 2018; Smith and Burkle, 2019; Skryabina et al, 2021).

A large number of responders within the studies were from hospitals not ambulance services, which limits how generalisable the findings are to the paramedic population because of differences in training and scope of practice. Some argue that paramedics may be more psychologically prepared because of what they are routinely exposed to at work, and the unpredictable nature of their job encourages high resilience (Vandentorren et al, 2018).

However, a recent study found paramedics reported that training prepared them for operational procedures but this fell short when it came to preparing them for the complex personal stressors and human factors seen in a real-life TA (Hugelius et al, 2021). Training responsibility lies with local trusts to ensure major incident procedures and JESIP protocols are understood, through undertaking annual e-learning, for example (NARU, 2024). The training has been criticised for focusing more on organisational preparedness than the individual, which limits psychological preparedness (Day et al, 2021).

The types of injuries that may occur from a TA, such as blast injuries from explosive devices, or multiple patients with polytrauma are not regularly seen by paramedics (Craigie et al, 2020). Many study participants’ papers reported using skills for the first time or working outside their scope of practice (Bentz et al, 2021).

Undertaking unfamiliar tasks or being unable to perform led to perceptions of failure and guilt among study participants (Smith and Burkle, 2019; Bentz et al, 2021; Skryabina et al, 2021). This is reflected in the wider literature; a large study of the 9/11 TA in America in 2001 found responders to be at an increased risk of PTSD if they undertook roles outside their usual remit (Perrin, 2007). This unfamiliarity that leads to guilt is well established within the literature, and PTSD can develop as guilt prevents the processing of fear and promotes avoidance coping strategies (Wilson et al, 2006; Pugh et al, 2015).

Preparing staff for the lack of control associated with TAs may decrease symptoms of guilt that can lead to PTSD (Raz et al, 2018; Day et al, 2021). This will further support recent changes to standards of practice requiring paramedics to manage the emotional burden that comes with their working environment (Health and Care Professionals Council, 2023).

It is evident that working at the site of a TA increases paramedics’ risk of PTSD. While it is argued that no amount of training can adequately prepare paramedics to respond to the unpredictable nature of a TA, promoting psychological resilience among staff should be a crucial component of major incident training (Williams and Drury, 2009; Skryabina et al, 2021). The papers highlight aspects that, if incorporated in pre-event training, may reduce the risk of PTSD. These include: preparation to work with a loss of control; education on a range of emotional reactions that staff may experience; and training in psychological support for victims.

The broader literature argues that there is a lack of focus on preparing paramedics for the psychological aspects of their role in responding to a TA (Day et al, 2021). A similar lack of preparedness has been addressed in the literature surrounding aid responders to humanitarian disasters (Williams and Drury, 2009; Allen et al, 2010; Brooks et al, 2015; Harris et al, 2018). Organisations have been criticised for dispatching volunteers without psychologically preparing them for the trauma they will encounter (Berger et al, 2012; Macpherson and Burkle, 2021).

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2011) recommends psychological first aid for responders deployed to humanitarian disaster zones in place of psychological debriefing. This is evidenced to increase psychological resilience in a crisis response (Sijbrandij et al, 2020; Corey et al, 2021).

Psychological training is perceived as a critical protective factor for responders to traumatic events (Brooks et al, 2018). Addressing these aspects may reduce the psychological impact on paramedics who respond to TAs.

Incorporating changes into paramedic training will, however, require further research to ensure it improves individual physiological preparedness and be implemented under clear guidance (Skryabina et al, 2021). The exploration of how this may be implemented is outside the remit of this review.

Key Points

Conclusion

Paramedics in the UK are an integral part of the emergency response to TAs and are encouraged to work closer to the threat level. While this increases the emergency services’ ability to save more lives, if not mitigated, it poses a more significant risk to paramedics of developing PTSD. Further research is required specifically with the paramedic population to better understand this risk and how it could be managed.

Paramedics also need to be both psychologically prepared and supported in their response to a TA; an absence of these may increase the burden on their mental wellbeing. Training and education should be adapted to include education for paramedics so they can understand and normalise the extreme emotions they may experience.

Furthermore, individual stress management could be incorporated into major incident training to improve paramedics’ resilience in dealing with unfamiliar or unsettling tasks (Day et al, 2021). As organisations increase the capabilities of paramedics to work in these hazardous environments, the psychological impact needs to be understood and reflected in policy. However, for this to be effective, further research is needed specifically within the paramedic population. JPP