Universities play an integral role in shaping and preparing graduates for the future world of work. Work integrated learning (WIL) activities—sometimes termed student placements, practice-based learning, cooperative education activities, or workplace learning activities—are embedded into university course curricula to prepare students for future professional environments by allowing the integration of discipline-specific theory with the meaningful practice of work (World Association for Cooperative & Work-Integrated Education, 2010; Council of Ambulance Authorities (CAA) 2014; Universities Australia et al, 2015; Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), 2018; CAA, 2018; Silva et al, 2018).

WIL is capable of many varied forms, and is adaptable to different disciplines and organisational contexts (Jackson, 2013; Universities Australia, 2019). For example, a recent audit of WIL activities undertaken in Australian universities found that of the 555 403 WIL activities carried out in 2017, 43.0% were work placements, 23.3% industry projects, 9.7% fieldwork and 12.9% simulation (the remaining 11.2% were classed as ‘other’ WIL activities) (Universities Australia, 2019).

The current article examines a project where paramedic students were connected with outdoor recreation university students and with practitioners from emergency response agencies while they participated in 2 days of emergency simulations in austere environments. This novel, interdisciplinary and interprofessional WIL activity is described and then evaluated with reference to five themes of quality in WIL programmes.

Rationale for an interdisciplinary activity

Paramedic and outdoor recreation students have similar imperatives to practise first response skills in austere environments. Undergraduate paramedic students—traditionally embedded in the health sciences disciplines—are in preparation to work in domestic and international emergency and non-emergency paramedic settings across regional, remote and urban environments. Undergraduate outdoor recreation students, on the other hand, combine their practical experience in outdoor activities with knowledge of the natural environment, wilderness first aid, group leadership and planning, to work in the outdoor education and recreation sectors. Outdoor recreation practitioners undertake activities from leading young school groups on wilderness adventures, to facilitating outdoor-based adventures for tourists, and even providing corporate executives with teamwork and leadership training based in outdoor environments. Traditionally, both student cohorts have undertaken separate course-embedded WIL in the form of work placements, internships, and simulated high-fidelity emergency scenarios.

Although disparate disciplines, these students are connected by their roles as first responders, and also by the shared landscape of their future professional practice; both cohorts will work in uncontrolled environments that are demanding, challenging and dynamic.

Paramedic practice settings range from the uncontrolled and unpredictable (at the patient's side/out-of-hospital care), to location-based (events/industrial sites), community-based (home visits/clinics) and facility-based (in hospital/extended care) (Bowles et al, 2017). Outdoor recreation settings are similarly expansive, often encompassing diverse outdoor environments where there are limited resources, communications infrastructure and support. Outdoor recreation professionals are therefore often trained as first responders who provide first aid to casualties in remote locations, respond to emergency situations, and coordinate emergency responses.

The dynamic nature of paramedic and outdoor recreation practice settings necessitates autonomy, awareness, sense-making and resilience. This is particularly the case when considering that the daily work of these two cohorts will be inherently risky, traversing the interaction between humans and the dynamic environments of practice. The multifaceted nature of risk means that human judgement and decision making are critical components of its management (Slovic, 2010; Perona et al, 2019). The way these future professionals negotiate inherently risky, dynamic and complex environments will determine how successful they will be at achieving their patient care objectives.

Design of the WIL activity

The authors, who are practising paramedic and academic staff, designed and facilitated a weekend of emergency simulation activities in authentic outdoor learning contexts. Throughout the weekend, simulation activities were scaffolded with increasing degrees of difficulty until culmination in a large interdisciplinary and multiagency emergency scenario at the conclusion of the weekend. The scenarios were intended to immerse students in cognitively and physically challenging situations, while providing both students and emergency responders with an authentic learning experience.

The weekend of activities was conducted across beach and bushland settings in a national park, 40 kilometres from the university campus on the Mid-North Coast of New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Student participants were first-year undergraduate paramedic students and second-year undergraduate outdoor recreation students. This disparity in year level of cohorts was required as Wilderness and Remote First Aid qualifications are only completed by Outdoor Recreation students in their second year of study. Practising paramedics, surf lifesaving staff and land search and rescue staff from relevant emergency response agencies participated in the multiagency scenario.

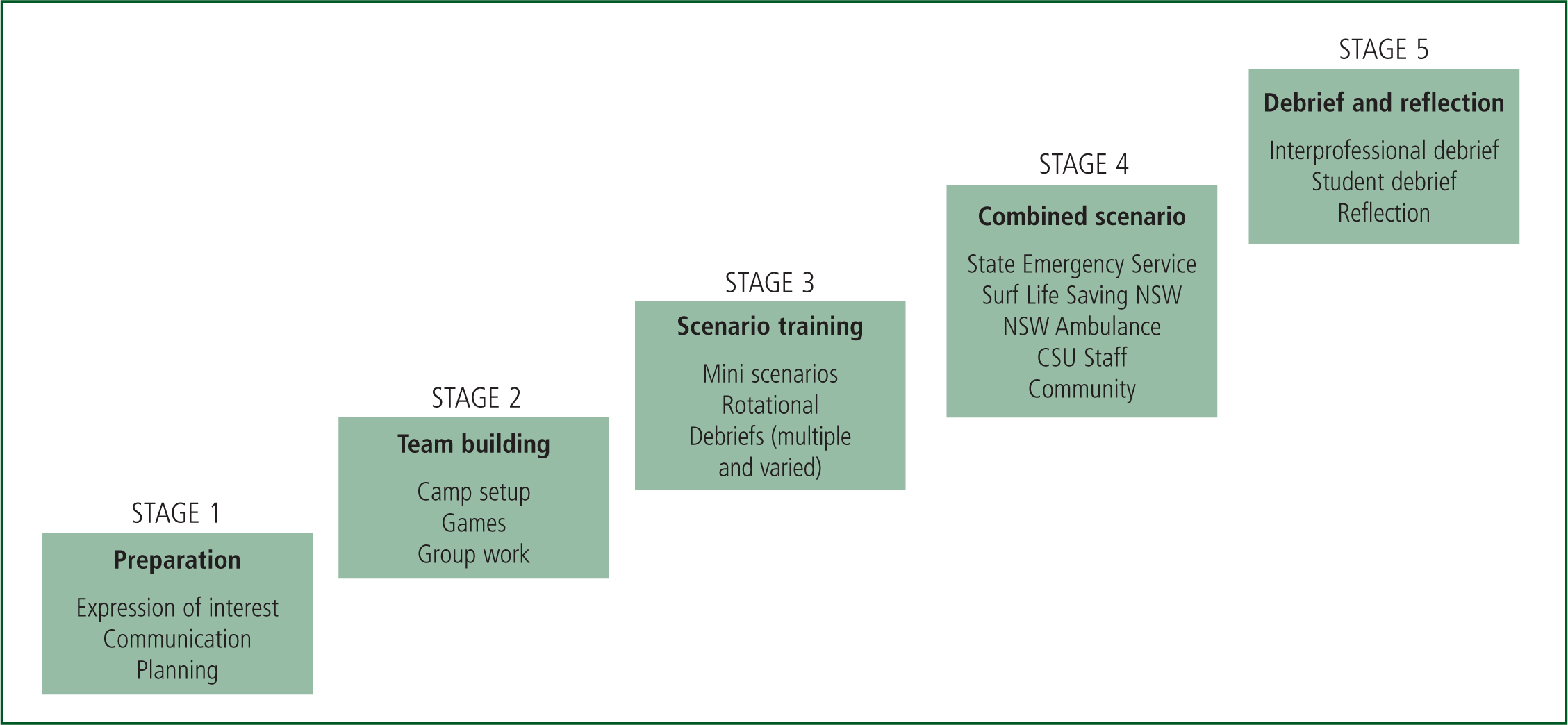

The WIL activity comprised five stages (Figure 1); the first three stages were designed to prepare students to operate effectively with one another and emergency agency staff within the multiagency scenario, while the final two stages were concerned with delivery of the scenario and fostering associated opportunities for learning.

Stage 1: preparation

Engaging students in the process of planning and preparation from the beginning was believed to be imperative to building social cohesion between the discrete cohorts, encouraging a sense of agency and level of ownership for the weekend's activities. The weekend was promoted via internal online communication to students, requiring the submission of an expression of interest in order for students to be allocated to one of the available places. Successful applicants were then provided with weekly online communication in the lead up to the weekend, providing information and instructions, and building a sense of community among participants.

Stage 2: Team building

The weekend of activities began with team-building exercises designed to bring the two disparate cohorts together. Mixed teams competed in problem-solving activities and physical challenges before coming together to organise camp setup and meal arrangements. Group work consisted of students instructing each other and becoming familiar with the use of equipment and their emergency response kits (Figure 2). Collegiality was essential in order to foster an environment where students felt supported in the activities, safe to make mistakes, and comfortable to share and learn from each other (Pearson and McLafferty, 2011; Marchioro et al, 2014).

Stage 3: Scenario training

Mini scenarios were developed by academic staff in consultation with practising paramedics and drawn from real cases (similar to Ford et al, 2014). Stage 3 consisted of rotations between three authentic scenarios situated in outdoor settings:

Interdisciplinary teams comprising up to six students were tasked to access, assess, treat and extricate the simulated patient. A debrief at the conclusion of each scenario—guided by academic and practising paramedic staff—allowed for adaptive learning and praxis. Each interdisciplinary student team then rotated to the next scenario, and so on, until all three were completed. Students were provided with minimal instruction from staff during each scenario, requiring them to use their skills in communication, problem solving and team work alongside their clinical skills to complete each activity. A final debrief was held at the conclusion of all rotations in order to facilitate whole-group reflection, sharing and learning.

Stage 4: Combined multiagency scenario

A multiagency and interdisciplinary emergency scenario was developed and facilitated by academic staff and industry partners the following morning. This large, complex multiagency scenario took place at a local public beach and involved a simulated helicopter crash, multiple physically dispersed casualties on land and sea, potential missing persons, and the need for in situ emergency treatment, as well as transport of patients to safe ground (Figure 3). Students were divided into two interdisciplinary groups and sent out to the emergency scene in two waves:

Students worked with emergency services staff to negotiate the complex and challenging scenario over a 90-minute period. Academic staff and industry partners also provided support and supervision throughout the scenario where needed. Purposefully situating the simulated activities in authentic outdoor learning contexts allowed the realities of the workplace to link clearly to the student learning experience (Flowers and Gamble, 2012).

Stage 5: Debrief and reflection

At the conclusion of the large multiagency scenario, a hot debrief was undertaken by each agency group separately, including the interdisciplinary student group. Students were asked to identify two areas of strength within their performance throughout the scenario, and one area for improvement. These three components were then taken to the multiagency debrief.

The multiagency debrief—attended by academic and supervisory staff, emergency response staff and university student participants—was undertaken in a manner consistent with the types of operational debriefs or after-action reviews carried out in similar professional environments. The structured debrief involved a walk-through of the emergency response scenario, identifying key decision points and actions taken (Figure 4). Following this, each professional group discussed two things that went well in the scenario, and one improvement they would like to see. By allowing them to participate, share and learn within the multiagency debrief, students were provided with authentic professional learning experiences within a community of practice that included all emergency agency staff and support staff who participated in this multiagency scenario.

Methods

A questionnaire consisting of 24 items (Likert scale, ranked response, and free-text-answer questions) was constructed to evaluate this WIL activity. The questionnaire sought to evaluate the WIL activity against five themes of quality which had been identified in similar paramedic WIL research (Delisle and Ebbs, 2018; 2019) and related studies (Williams et al, 2010; Willis et al, 2010; Siggins Miller Consultants, 2012; O'Meara et al, 2014; Sachs et al, 2016; Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, 2017). In these earlier studies (Williams et al, 2010; Willis et al, 2010; Siggins Miller Consultants, 2012; O'Meara et al, 2014; Sachs et al, 2016; Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, 2017; Delisle and Ebbs, 2018; 2019), it was noted that a quality WIL activity was one that:

For convenience, these five themes of quality have been named the WARDeR themes within this study (Table 1). While it is not proposed that the WARDeR themes are exhaustive or necessarily complete, they do provide a perspective to assist quality evaluation of paramedicine WIL programmes based on recent studies in this field.

| Theme | Description |

|---|---|

| W | Well organised: the WIL activity is well organised by the university and industry partners/professional partners |

| A | Accessible: the WIL activity is accessible to the student in terms of location, reasonable cost, and ability to participate in activities |

| R | Relevant: the WIL activity is clearly relevant to the student's course of study or chosen profession |

| De | Diverse experiences: The WIL activity exposes the student to diverse places, people and circumstances |

| R | Relationships: The WIL activity allows the student to build relationships with peers, preceptor(s), and professional staff |

The 24-item questionnaire was delivered to all student participants following completion of the WIL activity. This questionnaire was named the post-WIL survey. While the post-WIL survey sought to evaluate the WIL activity in relation to the above five themes of quality, it is noted that the post-WIL survey—having been recently developed for this study—can only claim internal validity. To further strengthen the study, a six-item questionnaire was also developed and delivered to student participants prior to commencement of the WIL activity. Within this pre-WIL survey, participants were asked to rank which of the five WARDeR themes they believed contributed the most to a quality WIL activity, and to quality learning within a WIL activity. Additionally, one free-text-answer question in the pre-WIL survey, and two free-text-answer questions in the post-WIL survey, invited participants to share further thoughts on the notion of quality within their WIL activities.

Descriptive statistics were used to analyse and compare ordinal and ranked-response data while deductive thematic analysis was used to identify alignment of WARDeR themes within free-text data. Further statistical analysis was not considered for ordinal and ranked data as low data volumes were expected (a maximum of 15 respondents were expected in each survey).

The Charles Sturt University Human Research Ethics Committee provided ethics approval for this study (Protocol Number: H18178).

Results

Fifteen students who were registered to participate in the WIL activity were invited to complete the pre-WIL survey and the post-WIL survey. Fourteen students completed the pre-WIL survey within 24 hours prior to commencement of the WIL activity, and fourteen students completed the post-WIL survey within 72 hours following conclusion of the WIL activity. In each survey, eight (of eight) Bachelor of Paramedicine students and six (of seven) Bachelor of Applied Science (Outdoor Recreation & Ecotourism) students participated in the survey. All respondents completed the survey in full.

Pre-WIL survey

In the pre-WIL survey, paramedic and outdoor recreation students were provided with a description of each WARDeR theme. Individual participants were asked to rank the WARDeR themes from one to five, where a rank of one indicated the theme was believed to contribute most to a high-quality WIL activity, and a rank of five indicated the theme contributed least to a high-quality WIL activity. Participants then repeated this ranking process, although this time were asked to rank the WARDeR themes in terms of their perceived contribution to high-quality learning during a WIL activity. These aspects of the pre-WIL survey helped to establish awareness of student expectations prior to the WIL activity.

Results from these ranked-response questions indicated that, prior to undertaking the WIL activity, participants believed that professional and academic ‘Relevance’ was the item that contributed most to a high-quality WIL activity (median rank=2, mode=2), and which contributed most to high-quality learning during a WIL activity (median rank=2, mode=2) when compared with the other WARDeR themes. The theme of ‘Accessibility’ (‘accessible … location, cost and ease of participation’) was ranked as the item contributing least to a high-quality WIL activity (median rank=4.5, mode=5) and least to high-quality learning during a WIL activity (median rank=4, mode=5). Low data volume and otherwise inconsistent results did not allow further meaningful analysis of these ranked-response data.

Within the free-text answers of the pre-WIL survey, the WARDeR themes of ‘Relevance’ and ‘Relationships’ strongly featured when participants were asked to describe what they believed contributes most to high-quality learning during a WIL activity. In Table 2, each of the free-text answers in the pre-WIL survey are provided, together with notation regarding thematic alignment of each statement within the WARDeR themes.

| Respondent number | Free-text response | Alignment with WARDeR theme/s |

|---|---|---|

| Pre1 a | Hands-on experiences that [are] interactive and fun to learn | Relevance |

| Pre2 a | Building relationships with people in the profession relevant to the students' course | Relationships |

| Pre3 a | Support from your peers, to make mistakes, learn and try things | Relationships |

| Pre4 a | Experiencing the different cultures, attitudes and range of individuals in the healthcare setting | Diverse experiences |

| Pre5 a | Hands-on learning | Relevance |

| Pre6 a | Communicating effectively and ensuring an understanding | Relationships |

| Pre7 a | Good communication between the student and staff on what to do. However, in saying that, allowing the student to ‘venture’ out on their own and learn to seek advice from staff for improvement | Relationships |

| Pre8 a | Group work with professionals and peers to gain valuable skills | Relationships |

| Pre9 b | Interaction between both courses | Relationships |

| Pre10 b | Fun times and first aid | Relevance |

| Pre11 b | Putting [our] learning into practice | Relevance |

| Pre12 b | Good working relationships with all students and staff involved | Relationships |

| Pre13 b | Practical involvement and knowledgeable instructors | Relevance |

| Pre14 b | Learning through peers | Relationships |

Bachelor of Paramedicine student;

Bachelor of Applied Science (Outdoor Recreation & Ecotourism) student

These ranked-response and free-text results indicate that, in the pre-WIL survey, participants viewed a quality WIL activity as one that was relevant to their course of study and chosen profession, and one that promoted student-to-peer and student-to-practitioner relationships.

Post-WIL survey

Within the post-WIL survey, participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with statements relating directly to each WARDeR theme. Three statements were generated for each theme, except for the ‘Diverse experiences’ theme, for which four statements were generated owing to the complex nature of this item. Participants were able to rank their level of agreement with each statement by using a five-point Likert scale, allowing participants to agree with a statement ‘to a very large extent’ (TaVL); ‘to a large extent’ (TaL); ‘somewhat’ (S); ‘to a small extent’ (TaS); and ‘to a very small extent’ (TaVS) (Table 3).

| WARDeR Theme | Survey question | Respondents' level of agreement with each statement (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaVL | TaL | S | TaS | TaVS | ||

| Well organised | The pre-placement administration (such as enrolment in the placement, information about the placement) was satisfactory | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| The placement was well organised by the University | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Industry champions or liaison staff from the profession(s) helped the placement run smoothly | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Accessible | It was relatively easy for me to get to the placement location | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I was able to meaningfully participate in placement activities | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| If I needed to, I was always able to contact someone for help | 11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Relevant | I was able to make clear connections between this placement and the learning in my current University course | 8 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| I was able to make clear connections between this placement and the activities likely to be required in my future professional career | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| This placement helped me acquire knowledge and skills that will help me to succeed in life outside of work and study | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Diverse experience | This placement occurred in a physical setting that I had NOT previously worked in | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| During this placement, I was able to interact with communities and cultures that I had NOT previously interacted with | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| This placement brought me into contact with professions or professional specialisations that I had NOT previously interacted with | 9 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| This placement brought me into contact with peers (such as other students) that I had NOT previously interacted with | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Relationships | During this placement, I was able to build a professional relationship with my assigned preceptor(s) | 10 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| During this placement, I was able to build professional relationships with peers (such as other students) | 11 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| During this placement, I was able to build professional relationships with other professional staff (NOT including peers or assigned preceptors) | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | |

| Totals | 138 | 56 | 22 | 6 | 2 | |

TaVL=To a very large extent; TaL=To a large extent; S=Somewhat; TaS=To a small extent; TaVS=To a very small extent

It is noted that the responses to each of these 16 statements which relate to the WARDeR themes are generally positive; for example, there were 194 occasions where participants provided a positive response to a statement (as defined by a participant selecting a response of ‘to a very large extent’ or ‘to a large extent’ on the Likert scale) compared with only eight occasions where participants provided a negative response (as defined by a participant selecting ‘to a very small extent’ or ‘to a small extent’).

When considering the emphasis that participants placed on themes of ‘Relevance’ and ‘Relationships’ in the pre-WIL survey, Table 3 shows that the WIL activity appears to have met these student expectations overall.

The one notable exception to this, however, was the final ‘Relationships’ statement found at the bottom of Table 3: The statement ‘During this [WIL activity], I was able to build professional relationships with other professional staff (NOT including peers or assigned preceptors)’ received only six positive responses (the lowest of all statements); five neutral responses (the highest of all statements); and three negative responses (the highest of all statements).

The authors believe that these results reflect a situation which occurred on the second day of simulations, where insufficient time was spent building relationships between student participants and a small number of staff from one agency. This contributed to disjointed execution of a task toward the end of the multiagency simulation.

Free-text-response questions at the conclusion of the post-WIL survey asked participants to specifically identify positive aspects of the WIL activity. Within these responses, participants recounted and partnered the themes of ‘Relevance’ and ‘Relationships’ (evident within the pre-WIL survey) with references to the theme of ‘Diverse experiences’:

Q: Upon reflection, what about this placement did you find most helpful in your learning?

‘Mixing paramedic skills and outdoor recreation skills to overall participate in a massive simulation. This was a great way to learn from each other.’

Respondent (R): Post2a [Themes: Relationships, Diverse experiences]

‘Practicing skills learnt in a practical setting whilst interacting with other services’

R: Post5a [Themes: Relevance, Relationships]

‘The ability to work in varying environments with professionals I have not previously interacted with.’

R: Post7a [Themes: Diverse experiences, Relationships]

‘The small scenarios we did on the first day. I felt we learned a lot about the paramedic side of things and how they operate. These also allow us to work in small groups where we could ask question[s] and making mistakes was a good thing [as it helped] us as outdoor recs who haven't practiced their first aid in a while to get confident again before the big scenario.”

R: Post10b [Themes: Relevance, Relationships]

‘Working with the paramedic students and getting an insight into how they deal [with] different situations’

R: Post13b [Themes: Relationships, Diverse experiences].

The final question of the survey specifically asked participants to discuss less helpful experiences within the WIL activity. In these responses, circumstances where ‘Relevance’ and ‘Relationships’ did not go as planned featured among other issues such as where ‘Accessibility’ and full participation in WIL activities was perceived to be compromised:

Q: Upon reflection, what about this placement did you find least helpful in your learning?

‘The last scenario for me didn't help much in my learning of skills as I wasn't involved much at all, I transported one patient and that was it. Would have liked to be more involved but [agency staff members] would not let me’

R: Post4a [Themes: Accessibility, Relevance]

‘People sticking to [their] own group and excluding me at times’

R: Post8a [Themes: Relationships]

‘It was not … ‘wilderness’ focused. There was little chance for us to practice key wilderness first aid skills such as improvising shelters and requirements and monitoring the patient for long periods of time.’

R: Post10b [Themes: Relevance]

‘… next time it would be best to involve different style scenarios. e.g. outdoor rec students are hiking or abseiling and someone gets injured, we begin initial first aid and then we hand over to paramedic students and they do their part …’

R: Post13b [Themes: Relevance].

Discussion

A key byproduct of interdisciplinary learning is the mutual appreciation and better understanding of different disciplines (Marchioro et al, 2014). Within this WIL activity, students were required to articulate and share their views with a new audience who may be unaware of the specific discipline language, skills and practices (Marchioro et al, 2014). Students mentioned the importance of gaining insight into a different discipline, learning skills and interacting with professional agencies. The strengths of this WIL activity appear evident within the interdisciplinary peer-to-peer learning which occurred within a new ‘community of practice’ involving paramedic and outdoor recreation students. The findings from this study emphasise the role that WIL activities can play in developing joint enterprise, mutuality and shared repertoire (Wenger, 2000).

The authors note that a comprehensive evaluation instrument for WIL activities in undergraduate paramedic programmes would require a much larger study, thoroughly investigating the necessary dimensions of quality within such WIL activities. Therefore, the pilot instrument presented here is intended as a guide, and the authors do not suggest that the pilot instrument is necessarily exhaustive.

A limitation of the present study relates to the small volume of data (especially the volume of free-text data) received, even though 14 of 15 participants completed the survey instrument in full. The survey instrument is not validated and hence can only claim internal validity at this stage, thereby representing another limitation of this study.

The WARDeR themes which have been used as a guide for evaluation appear to be appropriate when applied to novel paramedic WIL activities, such as the WIL activity described herein. While the WARDeR themes have been drawn from relevant literature, and further developed through two earlier research studies (as described in the Methods section), this is the first time these five themes have served as the basis for development of an evaluation instrument in paramedicine WIL.

In the present study, the evaluation instrument—which can be delivered as a questionnaire upon completion of a WIL activity—has been able to effectively evaluate a range of complex items which are central to the delivery of high-quality WIL.

Conclusion

Few would argue that the delivery of high-quality WIL is a simple endeavour. Therefore, evaluation of WIL ought not to be overly simplistic—such as to evaluate a WIL activity solely on the basis of ‘number of cases attended’ or ‘interventions performed’. These items are often relevant, yet quality WIL is a mixture of these and other elements, such as the development of sociocultural capabilities as well as psychomotor skills (Lazarsfeld-Jensen, 2010; Willis et al, 2010; Carver 2016: 17), professional socialisation, and relational competence (Michau et al, 2009; Williams et al, 2010; Ford et al, 2014).

To enable this complex learning, WIL programmes need to be well organised in partnership with host organisations who mentor the student throughout the WIL activity. The location of WIL activities, and the planned activities themselves, need to be accessible to the student and suitably diverse (Siggins Miller Consultants, 2012; O'Meara et al, 2014; Sachs et al, 2016; Winchester-Seeto, 2019) in order to prepare students for the diverse environments of future paramedic practice.

This pilot evaluation instrument, based on the WARDeR themes, may be suitable for wider consideration by those wishing to evaluate novel paramedic and interdisciplinary WIL activities. This is because, the authors believe, the WARDeR themes strike a balance between the complex elements of high-quality paramedicine WIL, while the pilot evaluation instrument provides academics and their universities an insight into how well these important elements of quality have been addressed within novel paramedicine WIL activities. To this end, the authors have included a pilot evaluation instrument that paramedic academics may wish to consider when evaluating novel WIL activities in undergraduate paramedic programmes (Table 4).

| Section | Question (and supporting notes) |

|---|---|

| Demographic questions | 1. Demographic questions can be posed at the beginning of the survey to address the needs of the evaluation |

| General experience questions | (Likert scale response: To a very large extent; To a large extent; Somewhat; To a small extent; To a very small extent) |

| Organisational and administrative questions | (Likert scale response: To a very large extent; To a large extent; Somewhat; To a small extent; To a very small extent) |

| Accessibility questions | (Likert scale responses, as above) |

| Relevance questions | (Likert scale responses, as above) |

| Diverse experiences questions | (Likert scale responses, as above) |

| Relationships questions | (Likert scale responses, as above) |

| Open comments section | (Free-text response question) |

For example, students may be more familiar with the term field trip, placement, or simulation, depending on the circumstances