Clinical leadership within the ambulance service has been under the spotlight since the publication of Taking Healthcare to the Patient (Department of Health (DH), 2005), which noted the importance of this key function within ambulance trusts. Recommendation 62 stated:

‘…there should be opportunity for career progression, with scope for ambulance professionals to become clinical leaders. While ambulance trusts will always need clinical direction from a variety of specialities, they should develop the potential of their own staff to influence clinical developments and improve and assure quality of care’

In 2008, the North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust introduced a new model of clinical leadership into the trust. The organisation adopted the concept of Skills for Health, career framework and set about implementing a variety of leadership roles, including consultant, advanced, senior and specialist paramedics. In 2007, the first consultant paramedic post was appointed, and this was followed in early 2008 with the appointment of 36 advanced paramedics. These clinicians operate 24 hours a day and respond to a variety of calls when senior clinical support may be required such as serious trauma and cardiac arrest. Fundamentally, however, these advanced practitioners are not part of the core operational response model. This allows them the appropriate time to provide the supervision and leadership required to fulfil their role. Part of their responsibilities includes providing remote telephone clinical advice to frontline clinicians.

Background

Telephone communication for consultation purposes is widely used in medicine (Thomas et al, 2001). This can range from nurses triaging patients, to the reporting of imaging or laboratory results. Training and education in communication for healthcare professionals including ambulance clinicians, is primarily focused on the interface with the patient and little attention is paid to the interface between healthcare professionals. Cohen (1998) recognised that the single most important component of successful consultation in any setting is effective communication. Communication failures have been estimated to be a major factor in 60–70 % of serious incidents and they been implicated as a cause of medical error and a threat to patient safety, (Lester and Tritter, 2001; Lingard et al, 2004; Greenberg et al, 2007). Improved healthcare professional communication has been shown to lead to improved patient outcomes (Braggs et al, 1999). Therefore when introducing systems such as remote telephone advice and consultation it is important to ensure they are safe and effective systems.

Requests for advice from frontline clinicians can be sought for a variety of reasons and these requests normally need to be dealt with urgently. It is recognised some of these calls can be challenging and complex, which may induce an element of pressure on clinicians. Wadhwa and Lingard (2006) identified five sources of tension with telephone consultations between doctors. These tensions included patient responsibility and reason for calling.

A number of studies have reported on the lack of clinical information being communicated as part of the telephone consultation process as a key issue and a risk to patient safety (Kuo et al, 1998; Cartmell et al, 2001; Greenberg et al, 2007; Marshall et al, 2009). This study sets out to explore some of the issues and challenges of providing remote clinical advice.

Method

A mixed method approach with an emphasis on exploratory qualitative orientation was employed to explore the issues, benefits and challenges of providing dynamic remote clinical advice to frontline clinicians by advanced paramedics. Many qualitative approaches use an inductive strategy, which is derived from the phenomenon where data is systematically collected and used to generate ideas. A mixed method approach can be defined as research that collects both qualitative and quantitative data in the one study and integrates this data at some stage of the research process (Andrew and Halcomb, 2009).

Sample

A purposive sample of 11 advanced paramedics and 70 frontline clinicians working across the North-West of England was selected to participate in the study. The ultimate goal of purposive sampling is to select information–rich cases from which researchers can obtain in-depth information needed for their studies (Morse, 2007).

Data collection

Two data-collection methods were employed: the use of two focus groups consisting of advanced paramedics and the distribution of 70 questionnaires to frontline clinicians who had experience of receiving remote clinical advice. In total, 56 questionnaires were completed representing a response rate of 80 %.

Data analysis

The data collected from the focus groups was digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. The data was analysed using descriptive, substantive coding and key emergent themes. The emergent themes were revised and refined throughout the analysis process.

Open, and subsequently selective coding was used in a deduction approach to refine the themes.

Results

The demographic details of the advanced paramedics who participated in the focus groups are identified in Table 1, and the details of the frontline clinicians who responded to the questionnaire are identified in Figure 1. It should be noted that the demographics are presented for background information and the details have not formed any part of the data analysis.

| Advanced paramedic participant | Age | Number |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | 20 |

| 2 | 49 | 23 |

| 3 | 40 | 18 |

| 4 | 40 | 17 |

| 5 | 39 | 12 |

| 6 | 33 | 15 |

| 7 | 49 | 30 |

| 8 | 35 | 14 |

| 9 | 39 | 14 |

| 10 | 42 | 16 |

| 11 | 38 | 14 |

Analysis of the data from the focus groups resulted in the emergence of five main themes; function, responsibility, barriers, education and support.

Function

All of the participants felt that providing remote clinical advice accounted for the majority of their working shift. The amount of calls varied from four to 14 per shift. Comments included:

‘I would say more of the job is advice calls than anything else, even responding. I am doing more advice than responding to incidents’ ‘I personally think it is the best part of my job because it gives you a direct way to support crews in difficult situations and we all learn from the experience’ ‘Previously, clinicians were given advice from a manager or control room operator who potentially was not a clinician and of those that were many had not been practising for some years’

Participants reported that they felt the introduction of their role had significantly improved patient safety and given clinicians support when they needed it. It was reported that on occasions, clinical advice was still being given to frontline staff from inappropriate sources, usually due to the unavailability of an advanced paramedic at the time. The questionnaire confirmed that remote clinical advice was still being provided from inappropriate sources, with six of the 56 participants reporting that they had received remote clinical advice from a person other than an advanced paramedic.

Responsibility

There was much discussion among all participants regarding the range of advice sought from frontline clinicians and where responsibility lies with regard to the decisions made. In the early days of providing this service, it was felt many calls were seeking confirmation on decisions already made:

‘It was not uncommon to receive calls from clinicians once they had cleared from an incident and to seek advice about a decision they had already made’

It was recognised by the majority of participants that this behaviour has virtually ceased altogether and the calls being received now were appropriate:

‘The majority of clinicians understand that the responsibility for the care provided to the patient rests with them and we are here to provide remote advice and support. We are not here to tell them how to do their job or take responsibility for the patient unless we are on-scene with them’

Focus group participants were clear in their belief that responsibility for the patient rests with the senior clinician on-scene and the role of the advanced paramedic was to support the decision making process by offering remote advice and to ensure the clinician had considered all of the appropriate options:

‘We are there to provide advice and support to the senior clinician you can be likened to the ‘phone a friend’ option on ‘Who wants to be a millionaire?’. The clinician does not have to take our advice but at least the support is there to discuss possible options to improve patient safety

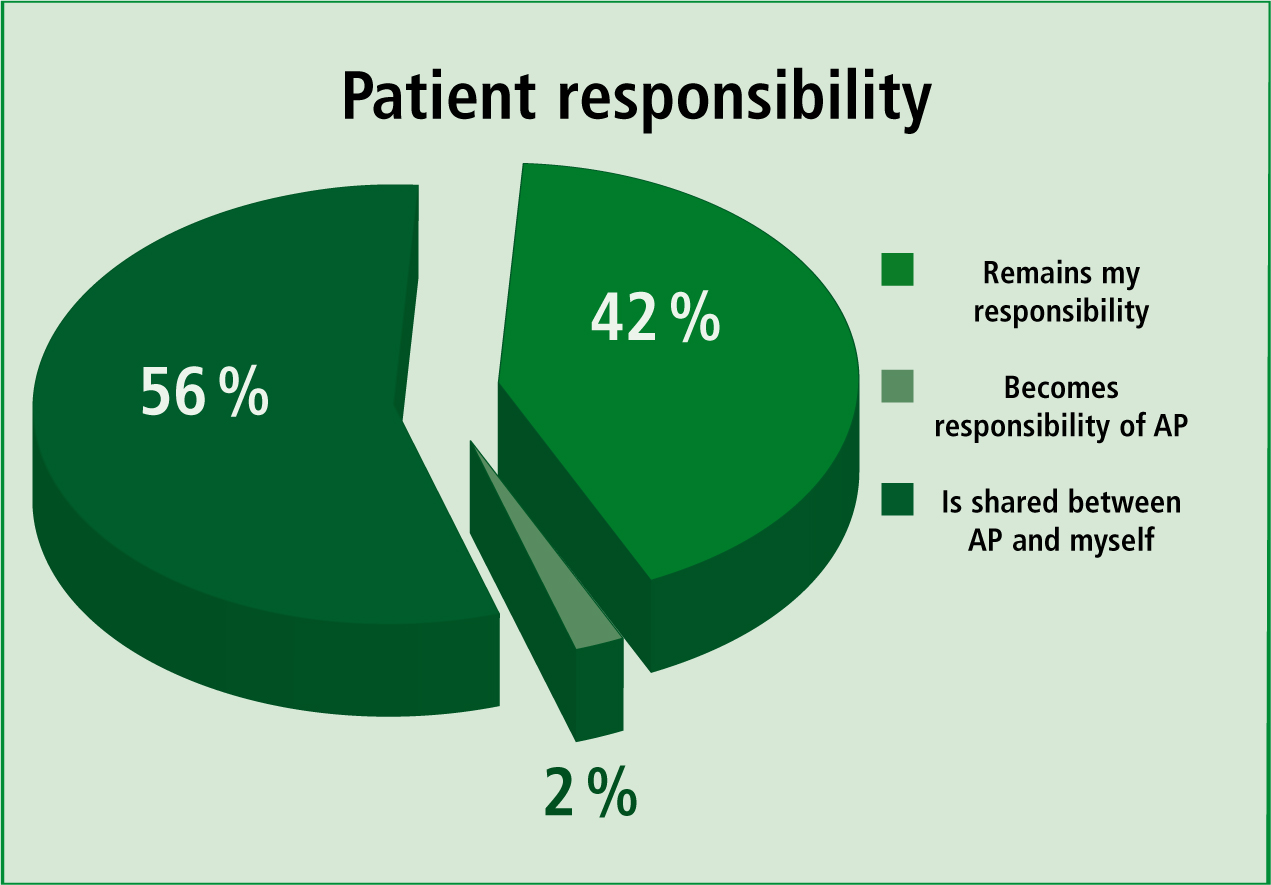

In comparison, although close to 100 % of questionnaire respondents believed that by following remote advice the patient did not become the sole responsibility of the advanced paramedic,56% believed that following receipt of such advicethe responsibility was then shared between thefrontline clinician and the advanced paramedic(Figure 2).

In addition, 46 % of the frontline clinicians reported that they always had to follow the advice of the advanced paramedic, with 54 % reporting they only have to consider the advice.

When asked about whether or not the advice given had confirmed, changed or had no effect on their decision making, 90 % of respondents said that it had confirmed their decision making with 7 % reporting it had changed it.

Focus group participants reported that the vast majority of calls received by the advanced paramedics relate to capacity to consent and drug administration:

‘80 % of the calls I receive are asking about capacity to consent. There is sometimes a view that if someone lacks capacity then they must be transported to hospital’.

When asked why they had turned to the service, 57% of respondents stated their main reason forseeking advice was after a patient had refused toattend hospital, with the second most commonlyrequested reason being capacity to consent.

Barriers and concerns

Participants in the focus group agreed there were common barriers that prevented clinicians from seeking advice. These included the feeling that an experienced clinician may be viewed as incompetent or lacking knowledge if they sought advice. It was reported that the majority of calls requesting advice came from clinicians with an academic background. It was felt this group of clinicians were encouraged to seek support and advice during their initial education compared to those who may have undergone education and training a number of years ago prior to the creation of the advanced paramedic role.

It was also recognised that a previous bad experience of receiving advice may also deter clinicians seeking advice in the future.

‘The majority of my calls come from lesser experienced staff who are mainly graduates from university’

The demographics of the frontline staff identified that 32 % of those who had requested advice were university paramedic graduates. When compared against the overall percentage of frontline staff who have acquired their paramedic education through the university route (13 %), this figure is proportionately higher than would be expected and would support the statements made in the focus group:

‘On occasions I have to ask the member of staff to obtain further information or observations from the patient’

It was reported in the focus groups that on occasions frontline clinicians did not have all the information to hand before they made contact with the advanced paramedic and had to return to the patient to ask more questions or obtain more test results.

Although a high proportion (98 %) of frontline staff reported that they had all the relevant information before they spoke to the advanced paramedic, 50 % were unaware of any structured model or tool to use when communicating information over the telephone and 59 % would like to see a model introduced. Advanced paramedics had concerns about the timeliness of their response to a request for advice,. especially when they were already engaged on a face-to-face or an advice call:

‘Quite often I have three or four advice calls to make, which causes frustration with clinicians who are waiting the call back’.

However, 90% of frontline clinicians were satisfied with the timeliness of call back by the advanced paramedic (Figure 3).

Education

It was recognised by both those seeking advice and those giving advice that this service provided a platform for sharing and improving knowledge and education:

‘Providing this advice to frontline staff gives great opportunity for learning. I had a member of staff who used to phone on a regular basis about capacity but his calls have reduced as he developed his knowledge base through the service we provide’.

All focus participants and 98% of the frontline clinicians believe the service provided is improving the education and knowledge of staff:

‘We need to be on the top of our game when providing clinical advice to our staff’

It was recognised that advance paramedics need to ensure their own knowledge and education are at the level expected of a senior clinician in a leadership role in order to provide the support and advice needed in a timely and efficient manner.

Support

It was recognised by all participants that there were a number of occasions when they were asked questions or advice on topics outside their own knowledge base or scope of practice. Overall, 70 % of frontline clinicians reported the advanced paramedic was able to provide the advice without the need to refer to a higher level clinician such as a consultant paramedic or one of the North West Ambulance Service (NWAS) employed doctors. However 30 % indicated the advanced paramedic needed to make contact with a more senior clinician.

‘There are times when things are outside my own scope of practice and I need to seek further advice, but on occasions have not been able to speak to one of the senior medical team’

This was a common theme throughout the focus groups. At present there is no formal system of on-call for the senior medical team, and advanced paramedics are reliant on attempting to contact one of six individuals at all times.

Discussion

Although providing clinical advice is only one part of the role of the advanced paramedic as a clinical leader, it amounts to a significant portion of the time spent during the shift.

The results of this study do show some similarities to that of other studies—responsibility played a key part in the focus group discussions and words such as abdication often came up, especially in the early days of the service being provided.

This concurs with Wadhwa and Lingard (2006), who recognised that responsibility was a tension between doctors during the telephone consultation process. Both focus groups recognised that with many of the calls they receive the decision about care and treatment had already been made and it was felt clinicians were seeking confirmation on their decisions, further supporting Wadhwa and Lingard (2006) who reported that consultants felt people are looking for you to bless or affirm their actions rather than seeking a true opinion, Hollins et al (2000), reported that referring doctors were looking for acknowledgment or agreement of their decision.

The results from the questionnaire would indicate this may be true, as 90 % indicated that the advice provided confirmed their thinking or decision. The duty of care also needs to be considered by both parties, and in particular, who owns the duty of care if advice is followed or not followed. Cartmill and White (2001) identified this as a key issue during the referral of head-injured patients to a neurosurgical unit. They discovered that most referring doctors assumed the duty of care transferred to the neurosurgical unit once the advice and referral had been made. However, in comparison, most doctors would only assume responsibility for providing competent advice on the issue they had been asked to advise on. However the paper concluded that in law, if advice was not followed and damage ensues then the referring doctor would be negligent.

Unlike Wadhwa and Lingard (2006) and Cartmill and White (2001), there were no concerns raised about medico-legal issues by the advanced paramedics during the focus group, as they always made it clear when giving advice that the lead clinician at scene has responsibility for the patient and the paramedic was there at the end of the phone to offer support, advice and guidance and to ensure all options had been considered. However, advanced paramedics will need to refect on their responsibilities, especially when their advice is followed, as 67 % of frontline clinicians who sought advice reported that when they followed that advice, the patient became a shared responsibility between the advanced paramedic and themselves.

Advanced paramedics also reported that on occasion, clinicians did not have all the relevant clinical information to hand when seeking advice. Most focus group participants had experienced an occasion when the clinician had not completed a full set of observations or had not gained a comprehensive case history before making contact with an advanced paramedic about leaving someone at home. Wadhwa and Lingard (2006) recognised this in their study and describe it as a fragmented clinical process, while Manian and Janssen (1996) stated:

‘The major pitfall with telephone consultations is that the recommendations of the consulting physician may be based on an incomplete, inaccurate or biased history or physical examination findings which may in turn result in incorrect or inadequate advice.’

With being remote from the incident means certain, less tangible aspects of assessment are missing, such as visual clues or ‘gut feeling’, and the advanced paramedic is therefore reliant on the clinician providing accurate information. Hollins et al (2000) found that one of the most problematic aspects of telephone consultation for specialists is having to rely on general practitioners’ experience and interpretation of signs. Kuo et al (1998), Walters (1992) and Cartmill and White (2001) all reported that insufficient communication of information during a telephone consultation was a risk to patient safety. The results of the questionnaire suggest that the majority of frontline clinicians did have the necessary information to hand when speaking to an advanced paramedic, however, over 75 % reported that they were not aware of any formal structure to present the information and over 75 % would welcome the introduction of tool to assist in this process.

Hollins et al (2000) found that the more experienced the referring doctor was, the better the communication was, with experienced doctors using effective ways of presenting information to the consultant, and concluded that junior clinicians would benefit from training in telephone consultation or guidelines to make the process less haphazard. Marshall et al (2009) explored the use of the tool identification, situation, background, assessment and recommendation (ISBAR) developed by the US navy for improving urgent communication aboard nuclear submarines (Box 1).

| I |

|

S |

|

If urgent say so. | Eg. This is urgent because the patient is unstable with a BP of 90 systolic... | ||

| B |

|

|

|

||||

| A |

|

Eg ‘So the patient is febrile and I can’t find a source of infection’. | Urgent, eg. ‘The patient seems to be deteriorating’/’I think they may be bleeding’. | ||||

| R | Recommendation State request. | ||||||

| Eg. I’d like your opinion on the most appropriate treatment plan. | Eg. I need help urgently—are you able to attend. | ||||||

The tool, recommended by the Institute of Health Improvement (US) was used as the model for healthcare practitioners to follow when communicating clinical information. Marshal et al (2009) undertook a study to test the use of this tool in telephone referrals. The study concluded that training in the use of ISBAR is feasible, effective and likely to result in improved communication in the clinical environment when making telephone referrals. The authors recommends, exploring an appropriate tool for use by ambulance clinicians.

Frontline clinicians agreed with advanced paramedics that the service they provide creates the opportunity for additional learning. This was recognised by Manian and Janssen (1996), who reported that consultations had an educational value especially when consulting physicians had to search for an answer to the query and that it engendered a sense of professional satisfaction from educating another physician and improving patient care. Wadhwa (2005) also reported in a qualitative study exploring telephone consultation and extending the opinion leader theory. They concluded that obtaining advice from an opinion leader through telephone consultation is perceived to trigger a change in practice and therefore may be an effective knowledge translation tool. The study also reported that using telephone consultation was an effective way of disseminating new information in an informal context and provides an element of reassurance to the clinician initiating the call. The study also highlighted the challenge expressed by consultants of the need to stay on top of issues which was a theme also expressed by the cohort of advanced paramedics. Over a quarter of frontline clinicians indicated the advanced paramedic needed to consult with a more senior clinician before providing advice and the authors suggests the advanced paramedics would benefit from introduction of a formal on-call rota for them to access further support or advice.

Limitations of the study

Findings from the study are limited as this was a relatively small-scale qualitative study. One particular limitation was that questionnaires were only distributed to frontline staff who had requested remote clinical advice in the past. No questionnaires were distributed to frontline staff who had never requested advice to identify if any barriers existed as to why this might be the case. Nevertheless the study has identified some important issues for practice, education and further research.

Conclusion

The study concludes that the introduction of remote clinical advice by advanced paramedics is proving successful and is appreciated by frontline clinicians, with a very high satisfaction rating. Furthermore, the data also suggests that requests for advice for appropriate challenging and complex incidents have increased while inappropriate calls have decreased.

Overall, the vast majority of frontline clinicians reported the introduction of remote clinical advice has improved patient safety, improved support for frontline clinicians and created additional opportunities for additional learning.

The study also identifies that clarity is required on duty of care and responsibilities. In addition, frontline clinicians would welcome a structured tool or model to communicate information when consulting with advanced paramedics and the authors suggest that further research is required to determine the most appropriate model to adopt.

Finally the study also identified that a formal on-call system was required to allow advanced paramedics to access advice when dealing with issues outside of their scope of practice.