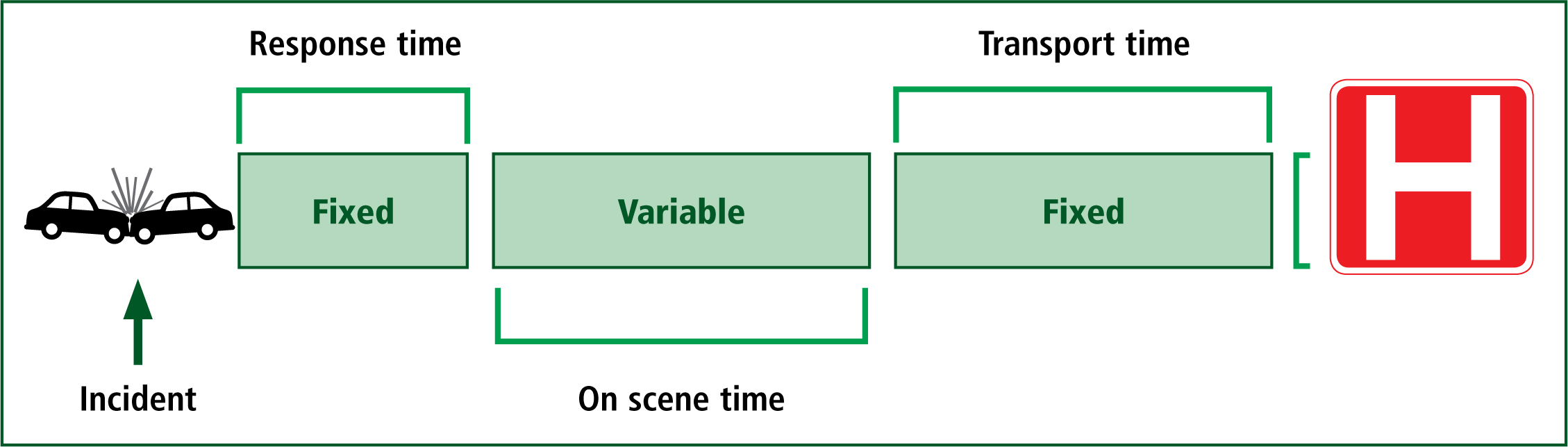

Motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) are the most common cause of major trauma in the UK (National Audit Office, 2010). Extrication of trapped patients following an MVC is reported to be required for 12% of patients (Wilmink et al, 1996), although international studies have found this number to be as high as 33% (Dias et al, 2011). The extrication period represents a key element of a patient's journey from the point of injury to arrival at a facility that can provide definitive care (Figure 1). For pre-hospital clinicians, their response time (from their location to the incident) and the total transport time (from the incident to the hospital) are essentially fixed time periods which cannot be changed for that patient, on that day, with the transport resources available at that time. Therefore, the total on-scene time represents the only truly variable element, of which the extrication plan and method make up a considerable percentage. The extrication plan and method can be adapted to meet the needs of individual patients, through multi-agency teamwork and appreciation of the priorities of care.

Extrication is challenging because of the rescuer's diametrically opposed objectives. The need for rapid access, thorough patient assessment and timely transfer to definitive care opposes the application of pragmatic principles, which endorse patient immobilisation and minimal movement for the care of presumed or suspected spinal injuries (Dixon et al, 2015).

The balance of risks and harms associated with rapid extrication compared to traditional extrication techniques is currently unknown, as this has not been studied with adequate scientific rigour.

The median time for extrication is 30 minutes for those patients who are both physically and medically trapped (Nutbeam et al, 2014). This represents a significant amount of the total pre-hospital time in a patient's journey following major trauma in the UK. International studies have demonstrated an association between prolonged extrication and worse patient outcomes; therefore strategies to reduce unnecessary delays potentially offer clinicians a significant opportunity to improve and positively impact patient care (Brown et al, 2016).

This article will report the incidence of medical and true physical entrapment in a cohort of UK patients following MVCs.

Methodology

This article reports data collected during a prospective, observational study carried out in the West Midland Fire Service's metropolitan area from October 2010–March 2012. All cases were patients who required extrication from an MVC. Data were collected consecutively. Initial publications aimed to examine extrication times and factors associated with delays (Nutbeam et al, 2014; 2015); however, this article specifically reports on the incidence of medical and physical entrapment in this cohort through a secondary analysis of the data.

Inclusion criteria were all requests for an extrication team or equipment where the patient had not self-extricated from the vehicle. Data were collected from vehicles designed principally for passenger transportation with a maximum capacity of seven people. Patients declared dead prior to extrication completion, those ejected and subsequently trapped, and where extrication equipment was not required were excluded.

Data were submitted by the attending fire crew via two-way radio and recorded on data collection forms for analysis. Crews reported the total number of patients involved in the incident and whether they were physically or medically trapped (Table 1). Examples are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

| Type of entrapment | Definition |

|---|---|

| Physical | Patients who required a vehicular intervention to create adequate space for extrication (could not be removed from the vehicle immediately, even if this was required). |

| Medical | Able to be immediately removed from the MVC if required; however patient required extrication for medical reasons (e.g. spinal immobilisation, pain, suspected injuries) |

Vehicles post-extrication

Figure 2 shows a vehicle post-extrication; findings were consistent with a physically trapped patient. The changes to the anatomy of the vehicle with significant intrusion means that the patient was likely trapped by:

Each of these entrapments requires a separate solution—door removal, dash roll (creating an exit space by pushing the dashboard forward using hydraulic rams) and pedal clearance.

Results

During the study period, there were a total of 245 MVCs where patients required extrication, all of which were suitable for inclusion; therefore, 296 patients were included in total.

There were 260 patients (87.9%) who were medically trapped and 36 (12.1%) who were physically trapped (Figure 4). Of the incidents, 229 MVCs involved solely medically trapped patients (33 involving more than on casualty) and 29 MVCs involved solely physically trapped patients (6 involving more than 1 casualty). Sixteen individual MVCs had a combination of both physically and medically trapped patients on-scene. A breakdown of the types of entrapment by MVC is shown in Table 2.

| Type of entrapment by MVC | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| MVCs involving solely medically trapped patients | 229 |

| MVCs involving solely physically trapped patients | 29 |

| MVCs involving a combination of medical and physical entrapment | 16 |

Discussion

This study compared the incidence of medical and physical entrapment in a cohort of patients requiring extrication following an MVC. In practice, it is evident that many patients are confined to the vehicle as a result of the current recommended extrication techniques; these are based on medical guidance, rather than true physical entrapment, which requires release and/or space creation. Examples of extrication methods are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Data have previously been published which demonstrate that the median time for extrication is 30 minutes using current ‘Plan A’ methods (such as roof removal and long spinal board (LSB)); this applies to those who are both physically and medically trapped (Nutbeam et al, 2014). In this study, the high percentage of patients who were medically trapped shows the potential to reduce the pre-hospital time and delays to definitive care, as the casualty could be freed immediately using strategies which focus on careful handling rather than immobilisation.

This time could be reduced in a number of ways, e.g. modifying extrication plan from a controlled access plan (Plan A) to a rapid access plan (Plan B) can reduce the total time of extrication by 7 minutes (Nutbeam et al, 2015). Additionally, self-extrication by the patient is intuitively quicker than either plan A or B, and has been demonstrated to produce less spinal movement than a traditional LSB extrication (Dixon et al, 2015).

Expert consensus opinion additionally supports this approach in the alert patient with no significant distracting injuries or overt evidence of intoxication (Connor et al, 2013). Effective communication between medical and rescue personnel is essential to ensure the immediate priorities for each patient are identified. Adequate dialogue and understanding of the patient's unique needs present an opportunity to provide variations to standard extrication techniques.

The concept that potential spinal injuries increase pre-hospital time is important, and should be balanced with evidence demonstrating that up to 15% of major trauma deaths could potentially be prevented by the early recognition and definitive management of life-threatening injuries and their sequelae (Kleber et al, 2013). Additionally, evidence demonstrating the overall low incidence of spinal cord injury following major trauma, the lack of proof of efficacy of spinal immobilisation practices, coupled with low numbers of true physical entrapment in this cohort should be considered by clinicians attending MVCs. Restrictions affecting patient examination and treatment in the confines of a vehicle offer a considerable challenge that can potentially be overcome by modifying current techniques to achieve earlier release of the patient. This should be considered on a case-by-case basis, as potentially preventable deaths continue to occur worldwide and earlier access to lifesaving interventions and definitive care may have the potential to improve patient outcomes.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study that should be considered. Primarily, it is a small study that may only be reflective of the geographical area in which the cases were collected. This has the potential to limit the generalisability of the findings, although the results appear to hold good face validity in the authors' experience. There is also the potential for reporting bias, as the attending fire crews may have over- or under-reported the occurrence of either form of entrapment. However, this is less likely as the observational nature of the study required simple reporting of the findings on scene, rather than any changes to current practice. Finally, the study did not collect data relating to patient injuries (either suspected or confirmed); therefore, the relationship between medical and physical entrapment in terms of overall mortality and morbidity is unclear.

Conclusion

This study documents the incidence of medical and physical entrapment following MVCs in a region of the UK. The low incidence of physical entrapment offers the opportunity to reduce the overall pre-hospital time for patients and provide earlier access to definitive care by the modification of ‘best practice’ extrication methods. This must be balanced with potential risks of unstable injuries and the analgesia requirements of the patient. Bespoke plans are likely to be required to optimise individual patient outcomes, although this requires further rigorous scientific study. Additionally, the earlier release of medically trapped patients has numerous other potential benefits, e.g. adequate space for thorough medical assessment and interventions, earlier release of committed emergency service resources and the prompt reopening of highways. Further examination of the optimum methods for patient extrication is urgently required to inform contemporary practice.