For many patients suffering from an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) within the pre-hospital setting, paramedics are the first contact within the scope of emergency healthcare. Patients suffering from an acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are cared for in the community by such healthcare workers on a frequent basis. Care pathways for these patients have evolved over the recent decade with the introduction of thrombolytic therapy; although this has now been superseded with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI). PPCI is now widely accepted as the reperfusion therapy of choice when placed next to thrombolysis for STEMI (Keeley et al, 2003).

As a result of research supporting the use of PPCI, the paradigm of care is ultimately moving to one of emergency ambulance transfer to a regional intervention centre. However, ambulance crews are now transporting these patients without a reperfusion strategy or indeed an adjunct for PPCI in place. Although such a venture is clearly plausible and empirically supported, it should be recognized that many ambulance services face challenges associated to the extended transfer times of rural locations. It would be unwise to accept that all STEMI patients are stable, at low risk of deterioration, and can tolerate excessive symptom and journey times. The early indications are that pre-hospital administration of a glycoprotein inhibitor (GPI) may well be the answer to improving the clinical outcome of the STEMI patient experiencing lengthened transfer time to hospital for target vessel re-canalisation (TVR). As a result, it is the purpose of this article to discuss and consider the possibility of the paramedic based community administering a glycoprotein inhibitor IIb/IIIa for STEMI within the out-of-hospital context.

The optimal care for the out-of-hospital STEMI patient now revolves around early diagnosis and timely ambulance transfer to the regional PPCI facility for reperfusion therapy. Once the patient has received TVR within the catheterisation laboratory, patients are administered a pharmacological agent in the form of a glycoprotein inhibitor IIb/IIIa (GPI IIb/IIIa) which typically is either Abciximab or Tirofban to prevent further platelet aggregation. The literature search found evidence that the use of a GPI, together with a loading dose of Clopidogrel during the pre-hospital phase for the STEMI patient led to improved clinical outcomes. Typically the primary endpoint within the research conducted around the use of GPI IIb/IIIa was quality of fow achieved within the occluded artery; with clinical endpoints defined as death, repeated re-vascularisation of the infarcted artery, non-fatal re-infarction, and major bleeding.

Glycoprotein inhibitors

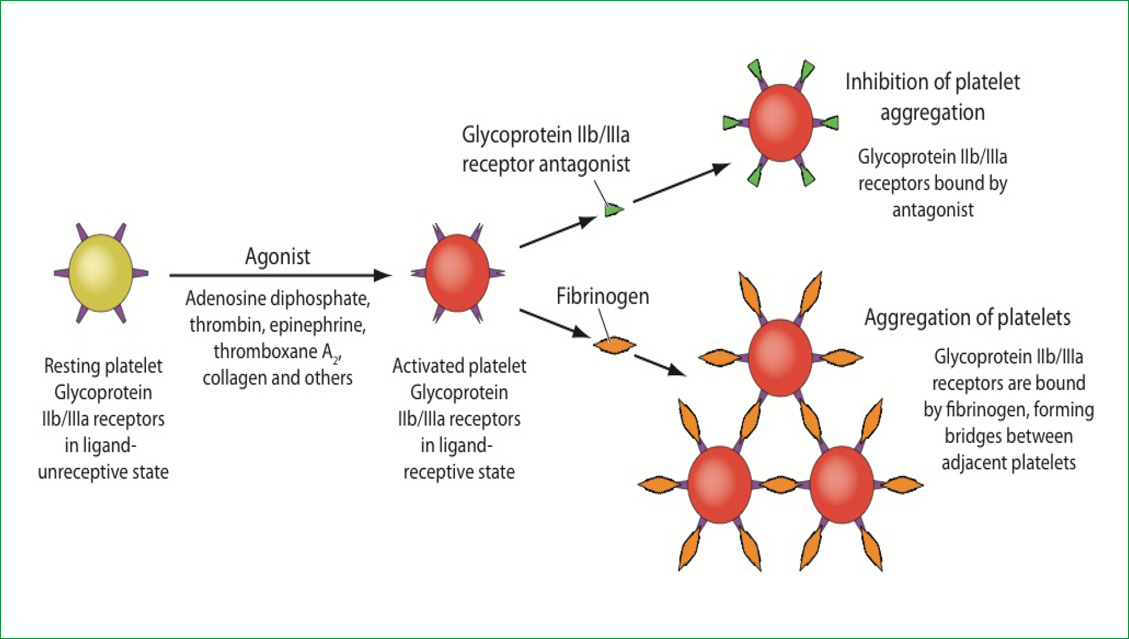

The mechanical action of GPI IIb/IIIa is inhibition of glycoprotein receptors IIb/IIIa (GPR IIb/IIIa) on the surface of platelets, preventing platelet aggregation (Figure 1). Activation causes changes in the shape of platelets and conformational changes in GPR IIb/IIIa. This causes the receptor to bind fibrinogen molecules which forms bridges between adjacent platelets thus facilitating aggregation. Inhibitors of glycoprotein's also bind to these receptors blocking the binding of fibrinogen and thus preventing platelet aggregation.

This mechanism is different to that of conventional anti-platelet therapy such as Aspirin which is supported within current ambulance practice guidelines (Joint Royal College and Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC), 2006). Typically, GPI IIb/IIIa are delivered within the catheterisation laboratory, thus preventing

further thrombus formation and prohibits post intervention debris becoming problematic. GPI IIb/IIIa are intravenous agents; Eptifbatide and Tirofiban are classed as small molecule inhibitors, while Abciximab is a humanised monoclonal antibody fragment (Jimenez and Tricoci, 2010).

Policy context

The role of PPCI and the use of GPI IIb/IIIa are well documented within health policy. The optimal treatment of acute myocardial infarction was clearly defined within the National Infarct Angioplasty Project (NIAP) which gave a clear message that PPCI was clearly beneficial in terms of clinical outcome and cost effectiveness, when delivered within a time window of 120 minutes (Department of Health (DH), 2008a). Lord Darzi (DH, 2008b) commented that there must be commitment to ensure that clinically cost effective innovation is adopted within health care services. What must be noted is that presently PPCI services are not available for all within the UK. For example, West Cumbria within the North West of England offers no PPCI services for its catchment area—for it is here that the STEMI patient will either experience a significant ambulance journey time to a PPCI facility and will receive the now considered suboptimal treatment of pre-hospital thrombolysis (DH, 2008a). The Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) (DH, 2008c) and the National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease (DH, 2008d) clearly identify that there is still a need to improve cardiac services and still advocates the use of pre-hospital thrombolysis for patients with extended transfer times. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2002) published its guidance on the use of GPI IIb/IIIa for acute coronary syndromes; it concluded that the role of GPI IIb/IIIa is advocated for patients who are at high risk of developing a significant infarction and should be administered a GPI IIb/IIIa whether or not PPCI is indicated early. This conclusion from NICE would seem to give the importance of GPI IIb/IIIa use further significance for the pre-hospital setting.

A review of the literature

It was identified that the research which had been conducted around the use of a GPI IIb/IIIa within the pre-hospital setting had been done outside of the UK using the GPI Tirofiban or Abciximab, although NICE does support the use of Eptifbatide (an alternative GPI). The literature was a collection of meta-analysis and randomized clinical trials; any research pre–2002 was not included in an attempt to catch the most contemporary up-to-date studies available. The search initially considered the role of GPI IIb/IIIa within the out-of-hospital environment, however this search was widened further to include the GPI IIb/IIIa Abciximab and Tirofiban. Studies that were based around the in-hospital context were also included, as the amount of out-of-hospital GPI IIb/IIIa studies was limited. The intention of the search was to identify what is currently known with regards to pre-hospital administration of GPI IIb/IIIa for the STEMI patient.

Relevant Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used to locate the appropriate literature (transportation of patients; emergency medical services; coronary vessel; percutaneous coronary intervention; angioplasty; balloon, coronary; myocardial infarction; platelet aggregation inhibitors; glycoprotein GPIIb-IIIa complex; Abciximab; Tirofiban; emergency health services; emergency care; emergency medicine; anti-thrombolytic agent). The databases explored were MEDLINE from inception to 2011, Cochrane Library, CINAHL 1939 to 2011 and EMBASE 1980 to 2011.

Administering GPI IIb/IIIa within the pre-hospital setting

To potentially augment pre-hospital coronary care, recent studies have highlighted a potential benefit of administering a GPI IIb/IIIa within the pre-hospital setting (Borentain et al, 2004; Montalescot et al, 2004; Berg et al, 2008; Berg et al, 2010). All these studies concluded that early administration of a GPI IIb/IIIa within the pre-hospital setting together with a loading dose of Clopidogrel (an additional anti platelet agent) improved clinical outcome and reduced mortality in patients presenting with an out-of-hospital STEMI. The research suggests that a GPI IIb/IIIa such as Abciximab, in conjunction with a loading dose of Clopidogrel, can equate to a desirable outcome; Larson et al (2010) identified in a recent study that a loading dose of Clopidogrel gave less ischaemic complications for STEMI patients receiving PPCI. Abciximab was also identified as advantageous due to an improved left ventricular function with a lower incidence of heart failure (Hassan et al, 2009).

Although the literature search uncovered research that supported the use of GPI IIb/IIIa within the pre-hospital setting, some research found little effect to condone its use. Mehilli et al (2008) conducted a randomized clinical trial and concluded that Abciximab together with a loading dose of Clopidogrel yielded little clinical benefit. However, the primary end point of infarct size differed to that of the studies which found Abciximab to be favourable. Mehilli et al (2008) wanted to know if the use of Abciximab actually reduced infarct size; other studies investigated if administration improved ST segment resolution time and improved infarct related artery flow.

The trial conducted by Berg et al (2008) stated that triple anti platelet therapy (high dose Tirofiban, Clopidogrel and Aspirin) was not associated with an increased risk of bleeding. Boersma et al (2003), while conducting a meta-analysis of all major randomised clinical trials, concluded that GPI IIb/ IIIa reduced the occurrence of death or myocardial infarction in patients with ACS who are not routinely scheduled for early revascularisation.

Tirofibran in myocardial infarction evaluation

Boer et al (2004) produced an analysis of the results of the ongoing Tirofiban in myocardial infarction evaluation (On-TIME) trial which was based in the pre-hospital setting. They hypothesised that early initiation of Tirofiban would improve the quality of flow to the infarct related vessel (IRV) at initial angiography prior to PPCI. They concluded that the hypothesis was proved to be null as Tirofiban did not improve the flow of the IRV to a sufficient level. However, the researchers openly conceded that the lack of positive findings of the use associated to the GPI IIb/IIIa was potentially due to under dosing of the drug. Other comparable studies such as that offered by Hof et al (2008) delivered 25 mcg/kg to the patient group receiving Tirofiban in comparison to 10 mcg/kg offered by Hof et al (2004). Interestingly, the study of Hof et al (2008) did not administer a loading dose of Clopidogrel in unison with GPI IIb/IIIa.

Khoury et al (2010) also concluded that the use of Tirofiban was of little benefit. It was announced within this study that other research had neglected the comparison of pre-hospital Tirofiban administration to hospital administered Tirofiban. Hof et al (2008) had compared the randomization of 491 patients who received the drug in comparison to 493 who received a placebo, there was no comparison to PPCI administered GPI IIb/IIIa within this study. Both these studies at frst glance have some similarities although some exclusion criteria and randomization sequences within the research were dissimilar. Although carried out pre Khoury et al (2010), Montalescot and Borentain (2004) conducted a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs and concluded that early administration of a GPI IIb/IIIa within the out-of-hospital arena appeared to improve coronary patency with favourable trends for clinical outcomes. De Luca et al (2005) found that Abciximab made a significant reduction in 30 day and long-term mortality in patients undergoing PPCI.

Lack of research

For us to gain a clearer vision of the out-of-hospital use of a GPI IIb/IIIa such as Abciximab or Tirofiban further experimental research would be required. What is evidently clear is the lack of pre-hospital research within this field; much has been done with regards to the in-hospital context. Antoniucci et al (2003) agreed that Abciximab is advantageous for the revascularisation of the IRV, though this was biased towards the hospital setting. This research was supported by Montalescot et al (2007), who also came to the conclusion that the use of Abciximab in the organization phase for PPCI has a strong impact on the clinical end points of re-infarction or death (59 deaths within the Abciximab group and 90 in the placebo group).

Rural STEMI patients

STEMI patients located within the rural context offers increasing challenges to UK paramedic services which may be causing unnecessary clinical risk. Widimsky et al (2002) during a randomized trial came to the conclusion that long distance transport for PPCI vs immediate thrombolysis was safe for acute myocardial infarction patients. However this study was an in-hospital based study concentrating on inter-hospital transfers and as such cannot be applied to the paramedic setting. There is a lack of pre-hospital original research regarding the transportation of the STEMI patient to the intervention centre. It is well known that injury to the myocardium due to ischaemia can be rapidly problematic, lead to arrhythmias and even death without the appropriate intervention. Research which supports PPCI as opposed to on scene thrombolysis appears to be irrefutable. However, what does appear to be apparent is the lack of evidence to support the notion that out-of-hospital STEMI patients can be safely transferred over a long distance without the appropriate pharmacological support.

According to Dieker and Liem (2010) pre-hospital diagnosis of STEMI with direct notification of the catheterization laboratory and subsequent transportation to the intervention centre is an attractive treatment strategy, although may be problematic. However, what Dieker et al (2010) does allude to is that efforts should be made to organize a large-scale implementation of an infrastructure of pre-hospital diagnosis and direct transport to the intervention centre. Arguably, some UK based ambulance services are doing this, though not all. A UK infrastructure of all regions embracing PPCI arguably is a utopian one. However, until all healthcare trusts can deploy these coronary care facilities for all suitable UK regions, in-ambulance GPI IIB/IIIA administration may prove to be a fundamental step forward.

Paramedics and pre-hospital thrombolysis

If paramedics have the clinical ability to identify the appropriate patients for pre-hospital thrombolysis (Johnston et al, 2005), then it is a reasonable argument that paramedics can administer GPI IIb/IIIa as indicated. Whitbread et al (2002) gave paramedics a myocardial infarction diagnostic accuracy of 95% in comparison to 93% presented by senior house officers within the ED. Given the conclusions within this research it is praiseworthy to assume paramedics can identify which patients would qualify for GPI IIb/IIIa administration.

The clinical examination, diagnosis and reperfusion strategies of STEMI patients until recently resided within the medical model of emergency care, typically within the emergency department. However, since the inception of pre-hospital thrombolysis in 2001, paramedics have played a key role at diagnosing and autonomously delivering role defining therapy for such patients (Johnston et al, 2005). The identified literature would seem to support the hypothesis that the inclusion of a GPI IIb/IIIa together with a loading dose of clopidogrel, leads to favourable clinical outcomes. Although evidence clearly identifies that PPCI is the gold standard for reperfusion, rural patients experiencing delayed intervention may be placed at significant clinical risk. Suggesting that this intervention would be appropriate for paramedic use is plausible given the research findings and the unique position that such healthcare workers currently adopt.

However actually making this a reality could potentially be problematic; the licensing of the drug for paramedic administration under a patient group directive would need exploration, as would the financial implications of such an intervention. It is also an assumption that the identified research has commonalities with the population of the UK and English based out-of-hospital and in-hospital care services. It would be a recommendation that the possibility of a UK based research study integrated within a UK regional ambulance service is explored.

Conclusion

This article has explored whether the role of GPI IIb/IIIa within the pre-hospital arena for STEMI would be a feasible endeavour. Care of these patients has until recently focused on the delivery of clot busting agents in an attempt to salvage threatened myocardium. Pre-hospital care of the STEMI patient has now shifted from thrombolysis, with scientific research favouring the role of PPCI. However, simply transferring such clinically compromised patients with little in the way of intervention may be a precarious strategy as ambulance services are continually placed under pressure to deliver high quality care within the shortest possible time.

As a result, UK ambulance services need to consider the geography they serve; a ‘one size fits all’ approach to dealing with the STEMI patient bound for the PPCI laboratory is arguably not practicable. Evidently inner city patients suffering from the ill effects of a STEMI can be within a catheterisation laboratory significantly quicker than patients within rurally challenging locations; such patients may face significant extended call to balloon times.

What clearly is uncertain is how the role of Clopidogrel features within the suggested administration process of GPI IIb/IIIa. It is apparent that although the JRCALC (2006) support the use of Clopidogrel, not all UK ambulance services have included its use within their cardiac care pathways. As most studies have indicated, the use and effectiveness of a GPI IIb/IIIa within the out-of-hospital environment seems to be further escalated with the inclusion of loading dose of Clopidogrel. National and local clinical guideline developers would do well to consider the role and potential effectiveness of Clopidogrel together with a GPI IIb/IIIa within today's pre-hospital coronary care. Paramedics administering such an intervention will once again be placed at the forefront of cutting edge practice. Such a professional has proved its worth with pre-hospital thrombolysis, now the use of a GPI IIb/IIIa in this context potentially may be the new chapter in out-of-hospital coronary care. As such, GPI IIb/IIIa administered by paramedics may well be the answer for STEMI patients subject to extended ambulance transfer times identified for PPCI. If such a pre-hospital healthcare worker has the appropriate skill base and behaviour to make autonomous clinical decisions, then serious consideration must be given to the paramedic delivering this intervention. Research supports the use of a GPI IIb/IIIa within this context and must be considered if the pre-hospital care for STEMI patient is to be further augmented.