The term paramedic often evokes visions of the dramatic, fast–paced and even heroic misconceptions perpetuated, disseminated and sometimes engineered by modern media coverage, and which were, up until only recently, mirrored in paramedic training. In the UK, Australia, the US, Africa and all across the world this largely under-represented and misunderstood profession is undergoing a dramatic change in professional identity, responsibility and education.

Rogers and Reynolds (2003) portray such change as the very fabric of social care, while being an unpredictable, disruptive yet continual process of which the notion alone causes alarm. An inevitable aspect of both personal and professional life, change can have multiple impetuses, affect many people, encounter much resistance and is increasingly commonplace in the emergency and unscheduled care arena. Pinnock and Dimmock (2003) argue that without realistic definitions of objectives and outcomes, success cannot be measured and failure can often be rewarded. They further suggest that a service that is clear about its purpose is more likely to be effective than a service that is not, supporting Reynolds’ (2003) argument that an organisation’s primary task can be used as a benchmark to any proposed change. This is a rather disconcerting hypothesis for paramedicine, at a time of mixed attitudes towards the relevance of sociology, psychology, holistic care and conflicting ideologies of its true professional purpose. There has been a recent shift in focus in healthcare management from maintaining the status quo to deliberately stimulating change and encouraging innovation in order to make continual improvements (Martin and Henderson, 2001). With healthcare practitioners (HCP) now being expected to care for their service users (SU) holistically, by taking account of their physical, social and psychological care needs, any stagnant attitudes within this profession need to be challenged and changed, in order to deliver effective biopsychosocial care.

Purpose and objectives of changing attitudes

Department of Health (DH) (2005) and Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (2011) statistics state that the majority of a paramedic’s workload consists of psychosocial care; however this is perhaps not refected in the attitudes of their staff, leading to a potential discrepancy in the care being provided. With what the author sees as an obvious preference for physical and biomedical pre-hospital care among its staff, the purpose of the proposed change in attitudes is to promote discussion and question what it means to be a paramedic. The objectives are to advertise the relevance of psychosocial and holistic care to paramedicine, highlight any challenges to changing attitudes, explore ways in which to comprehend and overcome them and evaluate a method by which potential changes in attitudes can be measured. By highlighting clear and concise objectives, aims and goals, one is able to organise, implement and measure change systematically and arguably more effectively.

History of paramedicine

By analysing a professions’ history and making links between the past and present, professionals are better able to comprehend the rationale behind change, future developments, mistakes, successes and failures (Ralph et al, 2003).

Since its inception during the world wars, pre-hospital care in Britain has associated itself heavily with an emergency, traumatic and life-threatening workload, with its education mirroring this. During the 1960s this labour–intensive, poorly educated occupation saw a change in both its training and equipment resulting from the Millar Report (Taylor, 2010), which called for updated methods of staff recruitment and development (Millar, 1966). Similarly in Belfast and North America at around the same time, steps were being taken to dramatically improve out–of–hospital cardiac care and trauma management (Garmel and Mahadevan, 2007).

These calls for more in-depth knowledge of anatomy and physiology with increased training in trauma and resuscitation continued to form the British Institute for Healthcare Development (IHCD) technician and paramedic course, taught up until quite recently and representative of courses taught internationally. This training according to Kilner (2004), focused disproportionately on skills that were not representative of a paramedic’s true workload of frequently non-life threatening calls, and has now been all but replaced by university courses. Brady and Haddow (2011) argue that IHCD training was inherently an adaptation of a 44-year-old protocol driven training regime that did not mirror the demographic needs facing emergency and unscheduled care in Britain.

This view was supported by the (2005) Bradley report, which highlighted that the majority of 999 calls were psychological and sociological in origin, leaving as little as 10 % seen as emergency life threatening. University education for paramedics now focuses on anatomy, physiology, pathophysiology and arguably just as importantly psychology and sociology, to produce practitioners versed in all aspects of the holistic needs. The author questions if practitioners from this now hybrid of educational structures agree with this shift from a biomedical model of care to a biopsychosocial, and what relevance practitioners place on the psychological and sociological care needs of patients as part of their workload.

Review of current literature

A search was conducted of the emergency nursing and paramedic practice journals, alongside Pubmed, Cochrane, and Science-Direct databases, from 1990 to current date. The following key words were entered, both individually and in combination; pre-hospital, out of hospital, paramedic, community nursing, sociology, psychology, psychosociology, biopsychosocial and social-determinants-of-health. It is suggested by campeau (2008)that paramedic science lacks the history of a professional presence such as medicine and the occupational research base of nursing. It is therefore often thought of as a hybrid of knowledge and skills taken from other pre-established occupations, a stance that is clearly refected in the current literature. It is evident throughout the literature reviewed, which produced results predominantly from developed nations such as the United Kingdom, the US, Sweden, Australia and New Zealand, with a smaller amount originating from less developed nations, such as India and Ghana, that the majority of the literature focuses overwhelmingly on education, behaviour and staff wellbeing; with smaller parallels being identified between community nursing and psychosocial determinants of health.

‘The majority of 999 calls were Psychological and sociological in Origin, leaving as little as 10%seen As emergency life threatening’

Education

The paramedic profession, much like nursing, has transitioned globally into higher education (Baumann, 2008), and certain similarities between these two changing structures can be seen. Kilner (2004) as mentioned earlier suggestsin-line-with the DH (2005) Bradley report, that the paramedic curriculum needs to mirror demographic changes. This stance was recognised early on in nursing literature; Balsamo and Martin (1994) for example, attempt to review the content of sociology in the nursing curriculum, coupled with the most effective ways of teaching it. The professionalisation of paramedicine came many years later, and higher education literature now boasts courses balanced in both biomedical and psychosocial underpinning knowledge (Tanner et al, 2010; Taylor, 2010; Brady and Haddow, 2011). The need for psychosociology in paramedic education to progress professionalisation features heavily in a string of published papers and texts. Authors such as Spencer and Archer, 2006; Blaber, 2008; Donaghy, 2008; Stevenson, 2008; Mc Donell, 2009;Tanner et al, 2010;Brady and Haddow, 2011), all state why psychosociology is integral to a progressing profession. However there is little qualitative or quantitative research into what difference its inclusion in curricula has actually made or indeed the perceptions of its relevance among staff.

Edgley et al (2009) published their qualitative findings into the perceptions of student nurses confronted by a requirement to learn sociology within their curriculum. The paper highlights that few student nurses could remember specific material, however many had some understanding that an awareness of cultural differences was helpful for shaping their perceptions of the care offered to patients—one of many societal awareness’s that developed as their practice placement progressed. It became evident that there was a hierarchy of knowledge, leading students to apply more importance to a biomedical model of health, as opposed to a biopsychosocial.

‘it became evident that there was a hierarchy of knowledge, leding students to apply more importanc to a biomedical model of health, as opposed to a biopsychosocial’

This hierarchy of knowledge was also present in results from a paper by Jones et al (2010), investigating the experiences of first year student paramedics. This mixed method research study that used semi-structured interviews and attitude scales, sheds some light on students’ perception of psychosociology. Students felt it had ‘little relevance’ and that they ‘couldn’t relate it to the job at all’. Jones et al (2010) highlight that this preference for practical learning and strong dislike for psychosociology amongst other subjects is somewhat at odds with the profession’s own view of what should constitute the nature of modern paramedic practice. Both papers are unique and shed some light, predominantly on the perceptions of sociology from a relatively small group of students from two respective geographical locations. Jones et al (2010) include some demographic information about their participants where Edgley et al (2009) do not.

However the most striking limitation to these two papers is that they focus solely on students, whose experience of practice compares little to that of qualified experienced practitioners, highlighting a gap in the literature as applied to psychosocial education.

Staff wellbeing and behaviour

There are various published pieces linking psychology to paramedicine. However, almost all of them predominantly focus on the professionals as opposed to those who use their services— the latest of which, by Williams (2012) although discussing implications for nurse educators, investigates emotional labour and coping mechanisms for paramedics. This is a subject mirrored in a plethora of works, by authors such as Mitmansgruber et al (2008);Courtney (2010) and Halpern et al (2010), whose theses, all investigate fatigue, stress and emotional labour of paramedic shift workers. Academic textbooks such as Blaber (2008); Caroline (2008) and Barkway (2009), do focus heavily on the necessity of psychosociology, as applied to both patients and staff. However, these texts are arguably being bought predominantly, if not exclusively, by undergraduate students, whose attitudes towards the subject have already been alluded to in this article, highlighting the potential for investigation and educational intervention to equalise focus from staff to patients.

Coupled with staff wellbeing, the focus of much of the psychological literature focuses on the study of paramedic behaviour; again perhaps to the detriment of focus on our service users. The majority of the literature could be grouped into what Summers and Willis (2010) denote as ‘The Human Factor’; discussing factors that can affect individual psychological behaviour; the ability to care, (Wahlin et al, 1995), and the termination of resuscitation, (Hall et al, 2004).

Interestingly, we begin to see slightly more focus on understanding of public health and sociology, with literature surrounding the changing use of emergency services (Martin and Cole, 2002), and the medical decisions influenced by practitioner social values (Nurok and Henckes, 2009). There is also a larger amount of literature focusing on the need for appropriate and improved assessment of mental health patients from Shaban (2005); Roberts and Henderson (2009); Hawley et al (2011); Palmer (2011); Parsons and O’Brien (2011), all of whom discuss how paramedics regularly deal with patients needing psychosocial care. However, only one of whom discusses perceptions of paramedics regarding their role, education and training, organisational culture and interaction with allied professionals when attending suspected or known cases of mental illness. Roberts and Henderson (2009) using a mixed method research study of (n=74) staff, highlighted that the paramedic educators strongly advocated the need for psychological education, however participants thought their main role was that of transport and the treatment of immediately life-threatening conditions. This study, while showing us a glimpse similar to that of small British studies, used only a small sample size and itself calls for further research into the subject area; again showing a potential discrepancy in the dissemination of paramedic theory into practice. It highlights further literature based on paramedics themselves and not won those they serve.

Community nursing and social determinants of health

The author is able to draw parallels between community nursing and paramedicine more than other professions. There is a growing amount of literature professing the important positions nurses hold within the community, much like paramedics, as well as highlighting potential psychosocial issues and referring appropriately to Keady (2005) and Macleod et al (2011). The emphasis on community is such that US police are now being offered crisis intervention team training for officers responding to mental disturbance calls (Teller et al 2006). Although social determinants of health are on the majority of university curriculums for paramedicine, there is little literature highlighting its importance.

Fundamentally, Ashtekar and Mankad (2007) advertise the ability for paramedics as community workers to recognise social determinants of health, not only in the developed nations but also within the likes of India and Ghana; where they deliver dietary, sexual and general social health advice. Reeve et al (2008) portray expanded paramedic roles in northern Queensland to include public health provision and Edlin et al (2010) puts forward a strong argument for pre-hospital providers’ recognition of intimate partner violence.

Rhodes and Pollock (2006) show that emergency medicine is well positioned to bridge biomedical and public health approaches for preventing disease and injury and promoting health through population-based strategies targeted at the community. However, this appears to be one of very few examples of literature surrounding paramedics’ role in public health promotion and recognition of psychosocial determinants of health.

The relevance of pre-hospital psychosocial care

The term paramedicine is a relatively new phrase which has not been widely adopted. Sook (2001) argues that all major definitions of good general practice refer to the need to consider the physical, psychological, and social wellbeing of patients; perhaps contrary to the biophysical preference and focus of most paramedics, promoted by previously prescribed training. Hence the introduction of such a term perhaps exemplifies changes in a profession becoming parallel to medicine.

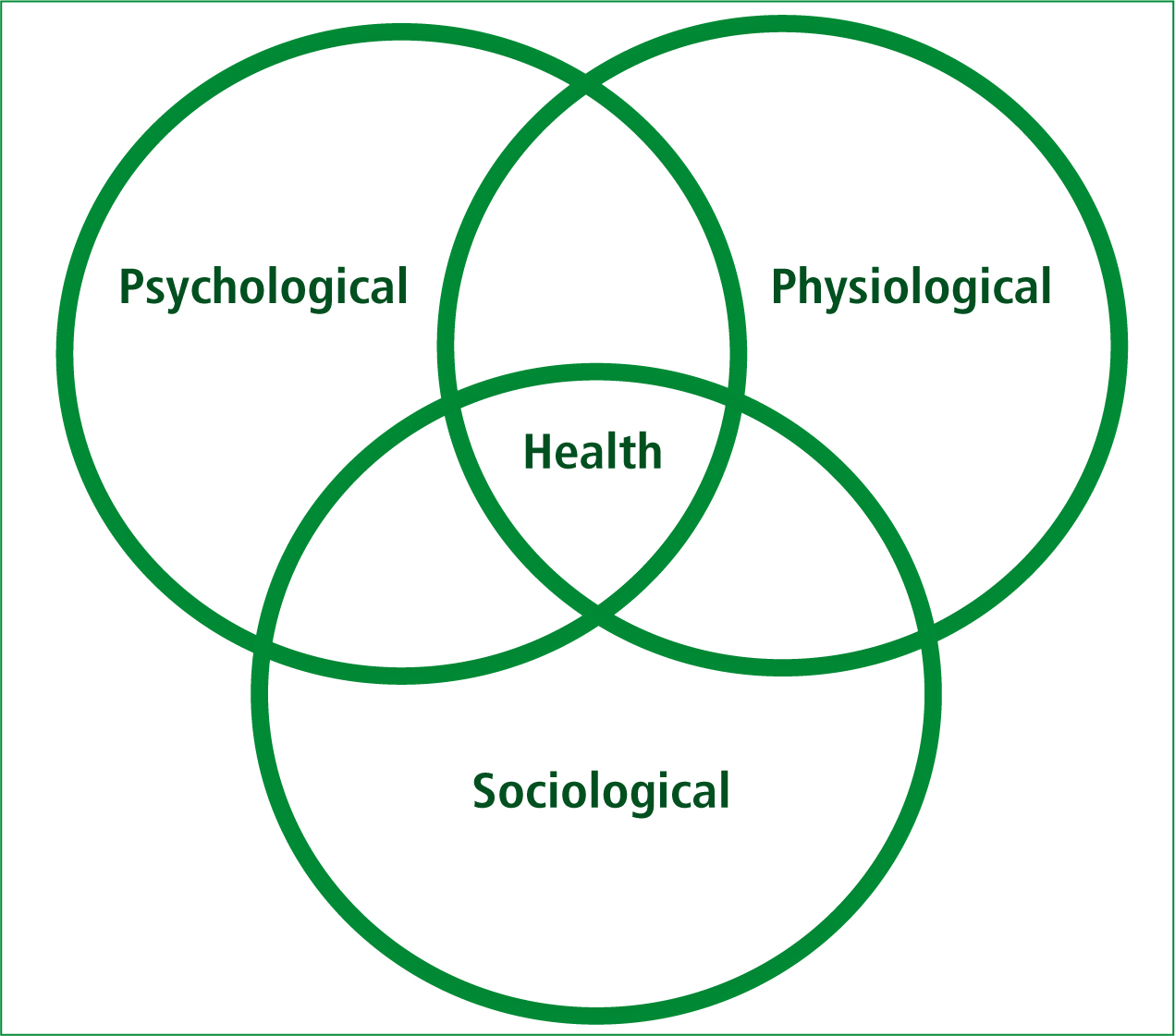

Stevenson (2008) states that the mind and body are not separate entities, they are inseparable parts of a whole human being, further highlighting the relevance of an holistic pre-hospital care approach, which we continue to explore (Figure 1).

Whitnell (2010) advocates the importance of psychology to paramedicine, explaining that the comprehension of mental processes and human behaviour of both individuals and of groups, can lead to better comprehension this interaction of not only the healthy but the vulnerable, elderly, children and disabled, all of whom paramedics regularly care for. Blaber (2008) also advocates the importance of sociology, explaining that paramedics are a unique type of community worker who see people in their own social world; if clinicians have a wider understanding of why and how people talk, act and respond to illness, they are able to adjust their own behaviour accordingly improving overall experience. This potentially highlights how paramedics are in an optimal position to recognise and investigate psychosocial determinants of health.

Psychosocial factors affecting health

The study of social class and evidence of inequalities of health, social exclusion, gender and ethnicity and their relationship to life expectancy is well established, however, paramedics come into contact with families and individuals months or even years before primary practice or social services are required—placing them in a prime position to be at the forefront of recognition, advice and referral. Social determinants of health are non-medical factors that affect both the average and distribution of health within populations, including distal determinants (political, legal, institutional, and cultural) and proximal determinants (socioeconomic status, physical environment, living and working conditions, family and social network, lifestyle or behaviour, and demographics) (Shi et al, 2009).

The frightening reality of this is best exemplified by Shaw (2005) who states that life expectancy decreases by one year for each of six stops on the London Underground if one travels from Tower Hill into the less affluent area of the East End. Shaw was writing in 2005 (before the globally acknowledged financial crisis of 2008), which, it could be argued, could only have exacerbated this degree of poverty and increased the gradient between rich and poor. Although the recognition of socioeconomic factors affecting the physical, social and psychological wellbeing of individuals, families and communities, may seem a far distance from what a paramedic job description may be, Berkman (2009) suggests that health disparities can be reduced if there is a better understanding of the forces that determine the magnitude of the differences among different social, economic, and racial or ethnic groups. Hence the necessity for paramedics to recognise psychosocial determinants of health is ever increasing, especially as the UK population for example, is expected to grow by 10 % over the next 20 years, with a large elderly contingent (Wanless, 2006), while simultaneously spending across all health and social care departments is expected to decrease in real terms by an average of 2.3 % (Appleby, 2009), further exacerbating disparities.

The majority of evidence suggests that material conditions are the underlying root of ill-health, as poverty imposes constraints on material conditions of everyday life (Smith et al, 1998); limiting access to the fundamental necessities of good health, adequate housing, good nutrition and opportunities to participate in society.

Adequate housing

The physical conditions in which people live can have detrimental affects upon their health, physically, socially and psychologically. Accidents are far more likely in poorer housing as items are either not repaired, or done so unprofessionally in order to save money, adding to the growing cost of poor housing to the NHS, which currently stands at £600 million per year (Houses of Parliament, 2011). Poorer people are less able to afford to constantly heat their homes, harbouring cold, damp, and often mouldy environments which in turn can lead to respiratory problems, aches and pains, diarrhoea, headaches, hypothermia and meningococcal infections (Wilkinson, 2009). In such conditions, people are far less likely to host friends for social occasions, including having school friends to interact with at home. This makes it unsurprising that poorer quality housing has detrimental psychological effects, such as social isolation, increased depression in women and the plethora of issues arising from overcrowding, such as emotional problems, aggression, developmental delay, bed-wetting, poorer educational attainment and mental adjustment in children, as well as relationship tensions, irritability and psychiatric disturbance (Blackman, 2008).

Good nutrition

Nutrition has long been recognised as an important contributor to health; diet is implicated in many chronic diseases and also affects oral health (Southern Public Health Unit Network West Moreton Public Health Unit (SPHUNEMPU), (2001). More affordable foods which poorer communities have little choice, to purchase, tend to have both high fat and salt content, which according to Caraher and Coveney (2003) directly affects consumers’ health, as it increases the likelihood of suffering from hypertension and other such cardiovascular diseases, such as strokes (Shi et al, 2009).

Philpin (2009) states that these types of food are more satisfying, please children and families, and to an extent, fulfil emotional needs. She goes onto to suggest that the embarrassment endured by poorer school children leads to a low uptake of free school meals, all of which compounds a failure to grow and develop normally, lack of concentration and childhood obesity. These psychosocial and dietary factors if recognised early by paramedics, whom advise and refer could be changed for the better; something the DH (2007) and Chiuve (2008) state, results in the reduction in the chances of having not just strokes but also diabetes and cancer more than any one factor.

Social participation

Poorer communities are often less able to interact in similar ways to those of more affluent families. Social exclusion refers to the process of marginalisation from various aspects of social and community life, as Philpin (2009) explains. Low socioeconomic status is linked with less access to both economic and social resources—educational opportunities, social networks and support, which in turn is very damaging to individual and community health. This is perhaps best seen in school children who are unable to afford to attend education excursions, after-school clubs and sporting events; all of which add to effective psychosocial development and growth. Schulz and Northridge (2004) argue that this social exclusion is not solely individual but applies to whole communities.

They continue to argue that areas such as safe parks and pathways that encourage play, which are so often left in dangerous and dilapidated states in poorer areas, encourage relaxation, exercise, and social interaction across social class and racial groups; leading to the development of stronger social networks and providing opportunities for physical activity and recreation. If paramedics enquire into the social history of individuals and families, they may uncover harmful behaviours abut which they are later able to provide helpful contact information for advice and support structures.

These determinants of health are not only being seen in the poorest echelons of today’s society but increasingly in lower-middle-class families and more so in the elderly who may be asset-rich but cash-poor. Conversely, one could be presented with an individual who is well off or wealthy, but has not spoken to family or friends for whatever reason in a prolonged time; leading to loneliness, depression and social exclusion, thus making it important for paramedics to apply these theories to every person they come into contact with.

The profession deemed by Millar (1966) as having the primary role of a transportation service is in theory fast evolving to match the demographic needs of its users, which are overwhelmingly psychosocial. However, the extent to which this theory is disseminating into practice, as well as to whether positive attitudes towards it are being engendered, is also in need of investigation.

Potential challenges and barriers to changing attitudes

Change can be alarming to staff and SU at all levels, harbouring and often engendered by, arguably its most prolific challenge, resistance. Ward (2003) states that where resistance to change is encountered there is usually a good reason at some level; by highlighting challenges and any potential sources of resistance managers are able to explore and overcome the often complex strategic, individual, organisational and cultural variables hindering change.

The Open University (OU) (2008) states that change can often be a top–down practice, being forced upon practitioners as part of ill-explained modernisation plans. Timmins (‘2011) argues that communication is a fundamental element of care at every level, without which the strong position managers are in to effect change can often be undermined; perhaps not solely by resistance, but by the poor communication resulting from the dynamics of emergency care, leading to a lack of knowledge of rationale, producing negative attitudes.

‘The media portrayed perception of paramedicine could potentially contribute to and engender attitudes that lack appreciation of psychosocial care’

Reynolds (2003) puts forward that changes often seek to refect public opinion and perceived need; however with continually negative media coverage surrounding response times, government targets, stroke and cardiac care (British Broadcasting corporation (BBC), 2010; Mirror, 2011), it might be said that the profession as a whole is disproportionally concentrating on what is seen to matter to the public through the media, arguably to the detriment of the less well publicised and romanticised psychosocial care, supporting negative attitudes towards its professional relevance.

The media portrayed perception of paramedicine could potentially contribute to and engender attitudes that lack appreciation of psychosocial care. Mursell (2012) questions the benefit of such media representation while advocating the need to influence the image of paramedics and to portray ourselves in the manner in which we want to be perceived. With mixed public perceptions of social workers highlighted in LeCroy and Stinson research’s (LeCroy and Stinson, 2004), compounded by more recent damning media coverage in the light of the ‘Baby P’ tragedy (BBC, 2010), it is unsurprising that paramedics may want to distance themselves from the social care aspects of their profession, further more perpetuating negative attitudes and fierce resistance to change.

The paramedic profession, much like nursing, has transitioned globally into higher education (Baumann, 2008), providing a foundation knowledge of sociology and psychology. Appreciation for such subjects is however being challenged at the first proverbial hurdle. As Jones et al’s (2010) research shows, many students fail to see their relevance and feel they are being educated to become academics rather than paramedics; thus disconcertingly presenting a challenge to proposed change even prior to undergraduate qualification.

The author suggests that this early resentment to psychosocial care engrained in a professional culture further challenges proposed attitudinal change. Skye et al (2003) refer to organisations as human systems with homeostatic equilibriums, describing culture as familiar habitual methods of engagement. These organisational cultures are sensitive to change and adaptation, often losing their integrity if introduced too quickly. Change may lead practitioners to question the efficacy of their past and current practice, something managers ought to be encouraging, nevertheless, challenging in the often sensitive, personal and distressing environment of emergency care.

The critical analysis thus far has focused solely on those whose attitudes the author would like to change. However, there appears to be a lack of consultation and empowerment for those SUs requiring acute psychosocial care, thus preventing clinicians seeing how proposed change is purely practice-led and evidence-based, perpetuating professional naivety and engendering negative attitudes.

When approaching the changing attitudes of practitioners, Rogers and Reynolds’ (2003) view that change affects those proposing it just as much as those subject to it, needs to be considered. Burnout is particularly prominent with healthcare managers (Laschinger and Finegan, 2008) and is described by Leiter and Maslach (2004) as a psychological syndrome of exhaustion, cynicism, and inefficacy, which is experienced in response to chronic job stressors, such as change.

By analysing potential barriers to change, we are now able to explore ways to comprehend and overcome them to progress this turbulent multidimensional process.

Overcoming barriers

The challenges identified are not just organisational and educational but also cultural and personal in origin. Ward (2003) stresses the importance of identifying people’s underlying reasons for resistance, so as to progress towards change. The author believes this can only be accomplished by encompassing a sound understanding of those affected; a theory mirrored by Rosen (2000) earlier work, that portrays good practice and management as involving and working with people to achieve goals. Skye et al (2003) explains that the way in which the author attempts to understand people has implications for how one manages them.

Only by listening, observing and refecting on why paramedics and students hold ideologies, attitudes and resentments towards psychosocial care, will one be able to allay fears, misconceptions, promote discussion and suggest ways forward. Through this use of emotional intelligence, depicted by Moon and Hur (2011) as the ability to appraise, express and understand emotion to improve teamwork efficacy and performance, barriers can be overcome and fundamentally change promoted. Just as understanding those affected by change is important, understanding the process of change itself is equally as so. Conceptually change is extremely complex and questions about the most effective way to bring about change continue to plague analysts in this field. While managers’ and researchers’ comprehension of change is beneficial in reducing barriers and challenges, they also need to recognise potential limitations in knowledge and be prepared to deal with any unexpected results.

Understanding those affected by change, the process itself and encouraging leadership, while all being potentially effective ways of overcoming challenges, could possibly be overshadowed by the simplicity of merely promoting practice led education and management to qualified staff and undergraduates. Built upon evidence based care, practice led management is the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values (International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2001), and by marrying the theoretical and practical elements of care provision, the author believes this unarguably highlights the need for psychosocial paramedic care and provides a foundation on which measurable outcomes can be obtained; evaluation of which we continue to discuss.

Evaluation of potential change

There is little data recording paramedic attitudes toward psychosociology, and mixed defnitions of a paramedics’ prime task, making recording outcomes against existing benchmarks somewhat difficult. There are many methods by which change can be measured; force field analysis for example is a diagnostic tool developed by Lewin (1951) that measures the forces driving change against the forces apposing it; with the forces representing the perception of people involved in change, it can be a useful evaluative tool (Rogers and Reynold, 2003), however, the author feels in this case sequential attitude scales and public consultation would prove most effective. Attitude scales involve respondents being asked to indicate on an ordinal range the extent of agreement or disagreement to a particular statement, and are used extensively in the collection of data in public health and social science research and evaluation (Thomas, 2010). Public consultation is a key component of government legislation and policy, giving psychosocial SUs a voice in matters that affect their lives and the ability to express noticeable change. One could also explore a liaison with psychosocial referral agencies, noting if a change in paramedic attitudes affects the number of appropriate direct referrals being made.

Pinnock and Dimmock (2003) previously suggested that with clear outcomes change can be measured. Through these evaluative and multi-agency processes, one is able to measure to what extend attitudes may have changed and thus to what extent SUs have benefted.

Conclusion

For too long now paramedics have deemed patients who are not physically ill an inappropriate use of their time. Ambulance services, universities and academic paramedics across the world are taking the first tentative steps into emphasising the importance of the sociological and psychological needs of individuals and communities, as well as the physical ailments which are very often a direct result of psychosocial factors mentioned in this article. Paramedics work in dynamic situations in varying environments which are often physically and emotionally demanding.

This flexibility and ability to think reactively now needs to be expanded and applied to the underpinning theories related to paramedicine. The media perpetuated romanticisms, while making good television need to be left behind and a new era of professional biopsychosocial paramedic care needs to be entered. Many practitioners are frustrated with the portrayal of paramedicine among other medical professions as merely a poorly qualified taxi service; however this view will not be forgotten and will remain unchanged unless we as a profession embrace an appreciation of holistic care, and the benefits it brings to those who we aim to serve.