The child with abdominal pain and/or vomiting is a common presentation to the emergency department (Marin and Alpern, 2011). Most have self-limiting conditions that can be managed with reassurance, fluids and pain relief. It is however estimated that approximately 25 % of patients (adults and children) calling ‘999’ for abdominal pain do have a serious underlying condition requiring intervention (UK Ambulance Service Clinical Practice Guidelines, 2006; Paul and Heaton, 2013). In children, surgical problems are relatively uncommon; however the cause and presentation of such a problem may differ from that commonly seen in adult practice.

Paramedic teams are often the first-line health professionals who will come across children with a suspected surgical problem and early recognition and appropriate initial management is the key to a good outcome. This article aims to give an overview of the common surgical problems encountered in children, along with some simple guidance to aid a quick assessment and transfer to the emergency department/ specialist services. While the specific surgical aetiology is rarely identified with certainty in the pre-hospital setting, it is important to remember that most of these conditions will need urgent identification and management, and time is of the essence. After reading this article readers should be able to:

Identifying surgical condition in children can be challenging

It is of paramount importance that surgical teams are involved early in cases where the situation can progress and rapidly deteriorate (e.g. intussusception or appendicitis) (UK Ambulance Service Clinical Practice Guidelines, 2006). The variation in presentation caused by age-related, idiosyncratic or non-specific presentations in children, however, increases the diagnostic challenge.

Therefore, whenever a suspicion about a surgical problem arises, the child should be transferred to specialist services. Some of the reasons why recognising and diagnosing surgical conditions in children can be challenging are highlighted below:

Surgical presentations in children can be age-specific

Most surgical conditions in children are likely to present with ‘lumps or bumps’, ‘abdominal pain’ or ‘vomiting’. Paramedic teams attending emergency calls need to remain aware of the specific age-related surgical problems in children and these are highlighted in Table 1. A detailed discussion about these conditions is described later.

Factors which may pose increased risk for surgical problems in children

It is important that paramedic professionals attending children remain aware of risk factors which may increase the likelihood of suffering from a surgical condition. Table 2 highlights some risk factors that should raise suspicion of a surgical problem. A quick focused history may reveal some of these risk factors and it is useful that the paramedic team highlights these when handing over the child to the clinicians in the emergency department.

‘Bile is bad’ and it is green

It is important to ask about the colour of the vomit in the child. Bile manifests as green coloured vomit and is a serious sign (suggest obstruction in gut) until proven otherwise after assessment and investigation. Parents often describe yellow vomit as containing ‘bile’ and the actual colour of the vomit should be clearly elicited, as for medical/ surgical purposes, bilious vomiting is green. Bile can be associated with life-threatening surgical conditions such as intestinal malrotation and intussusception. Children with bile stained vomit should always be brought to hospital for specialist assessment as these conditions may require further assessment and surgical treatment.

Identifying red flag symptoms

Surgical conditions can pose a challenge especially in young children; identification may be helped through recognition of one or a combination of red flag symptoms. Table 3 highlights some of the red flag symptoms that may enable paramedic teams to consider possibility of a surgical diagnosis early.

Common surgical emergencies in the pre-hospital setting

Inguinal hernia

An inguinal hernia usually presents as a swelling in the groin or a scrotal lump. This results from failure of the closure of processus vaginalis, resulting in protrusion of abdominal contents (intestine, omentum, ovaries etc) into the groin via the inguinal canal. It is more commonly seen in children under 1 year-of-age and its incidence is much higher (up to 30 %) in infants born prematurely (Spence et al, 1998; Zamakhshary, 2008; Paul and Heaton, 2013). Males have a predisposition for inguinal hernias with a ratio of 5:1 (Smith and Kenny, 2008).

A simple, non-strangulated inguinal hernia in infants is usually non-tender and reducible. This becomes prominent/larger when the child is crying or straining/coughing and disappears with gentle pressure or when lying down (Figure 1). However, the hernia becomes complicated if it becomes incarcerated/obstructed (that is, hernia cannot be reduced with gentle pressure) thus impairing blood supply which may lead to bowel ischaemia (Henning et al. 2013). A history of vomiting, colicky abdominal pain, poor feeding or constipation may suggest bowel obstruction secondary to such an incarcerated hernia (Spence et al, 1998; Zamakhshary et al. 2008).

Attempted reduction of the hernia at this stage is best being avoided in the pre-hospital setting and the child should be urgently transferred to the emergency department. Pain relief may be given during the transfer and attempts should be made to keep the child comfortable. Definitive treatment requires surgery; if an obstructed hernia is suspected, urgent surgical intervention is required (Henning et al. 2013). It is not uncommon, however, for carers to call for an ambulance when they find the hernia for the first time. If a hernia is found to be reducible and the child is well, this can usually be treated as an elective case and carers may be advised to contact their general practitioner so that an outpatient referral can be arranged. It is importanrt to give some simple advice about what to do should the situation become more concerning.

Intussusception

Intussusception is the most common surgical emergency in younger children and is caused by the telescoping of a proximal segment of bowel loop distally into an adjacent segment, leading to obstruction and, in some cases, subsequently leads to bowel necrosis (Rogers and Robb, 2010).

It is more common in boys (four males: one female) and typically presents between the ages of four months and two years (Paul et al. 2010). The aetiology in this age group is generally idiopathic, although an upper respiratory tract or gastrointestinal infection has been shown to precede the onset of intussusception in some cases. Children > 2 years of age are more likely to have an associated cause for intussusception, for example, HSP.

There are three classical signs of intussusception to be alert for, though not all occur in all cases: Intermittent colicky abdominal pain (with pulling up of the legs and screaming), bilious vomiting and the passage of blood per rectum (described as ‘red currant jelly’ stool for obvious reasons of similarity). In the majority of cases only one or two of these symptoms are present (Paul et al. 2010) and it should be noted that red currant jelly stool can be a late sign, associated with a less good outcome (Yamamoto et al, 1997). It is worth remembering other non-specific symptoms such as lethargy, listlessness, poor feeding or a gastroenteritis-like illness that just doesn't seem to be settling can be the only presenting features, especially in infancy (Paul et al. 2010).

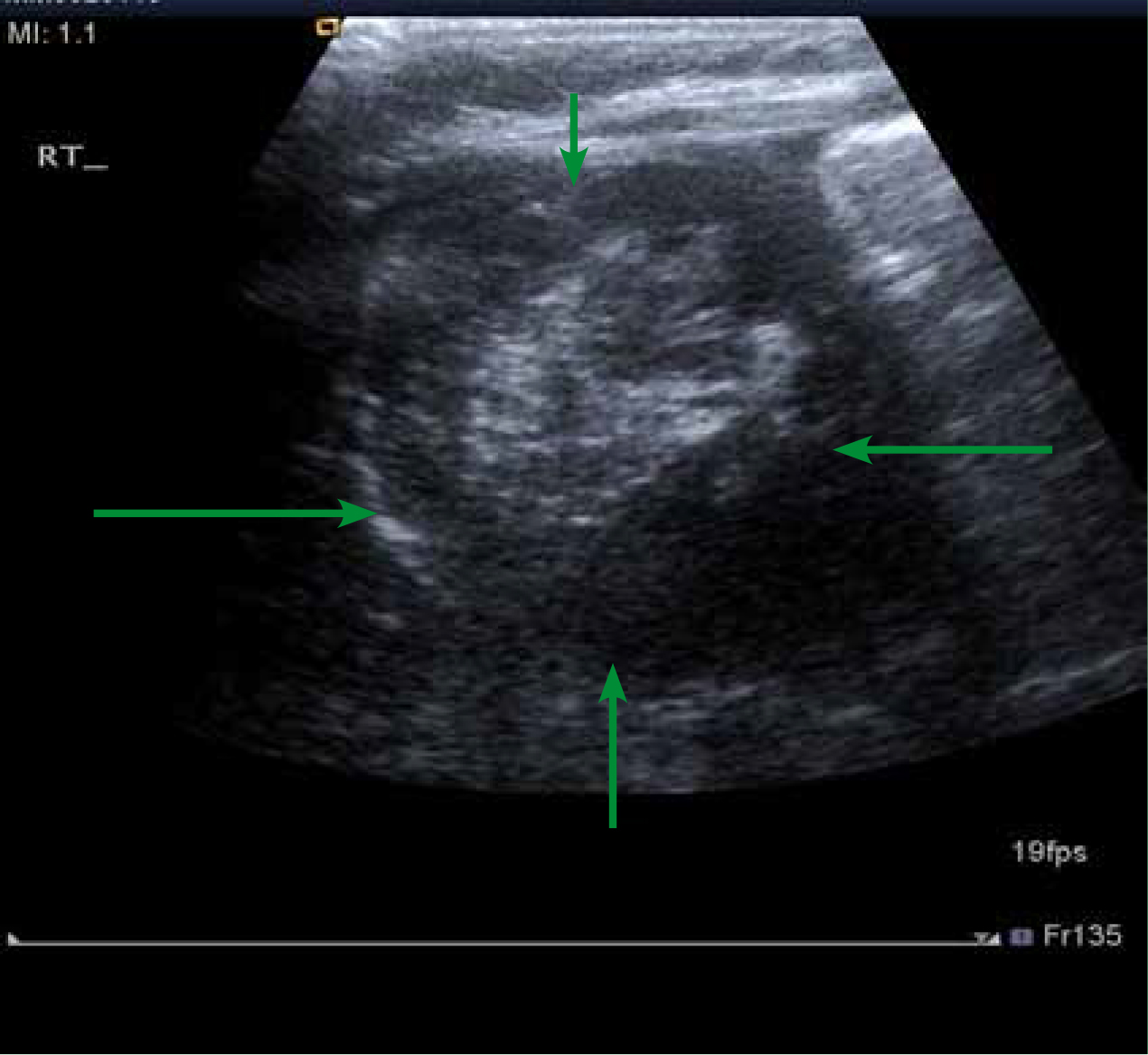

Paramedic teams who have any suspicion that they may be dealing with a case of an intussusception should always transfer the child to specialist services, as classical signs are often not present early, yet early intervention is associated with a better outcome. An ultrasound scan of the abdomen can confirm the diagnosis (doughnut sign) (Figure 2) and definitive treatment by air enema reduction under ultrasound guidance (in a centre where paediatric surgical expertise is readily available) is successful in most cases, although open surgery is still sometimes necessary (Spence et al, 1998; Paul et al. 2010).

It is important to remember that a small proportion (5–10 %) of children treated with air enema may have a recurrence of intussusception and these children should again be transferred early if a recurrence is suspected (Paul et al. 2010; Thayalan et al. 2013), and may require subsequent investigation to see why the problem is recurrent.

Malrotation and volvulus

Malrotation usually presents as a sudden onset of bilious vomiting, abdominal pain, poor feeding and/or refusal to feed. Distension of the abdomen is sometimes noted, but may not be remarkable (Kimura and Loening-Baucke, 2000). It is an anatomical abnormality, caused by incomplete rotation of the midgut around the superior mesenteric vessels during in-utero development. If left untreated, it can eventually result in twisting of the gut (volvulus) causing obstruction and/ or bowel ischaemia. Again, a male predominance is noted in this condition with a 2:1 ratio (Kouwenberg et al. 2008).

Malrotation most commonly presents in neonatal age group (birth to first 28 days of life) and should be treated as a surgical emergency, as the mortality from midgut volvulus has been shown to be as high as up to 28 % (Davenport, 1996). Neonates presenting late with bowel necrosis have a significantly increased risk of mortality (Kouwenberg et al. 2008).

A suspicion of malrotation is often raised from the history and the infant should be urgently transferred to specialist services. The diagnosis is made by an upper gastrointestinal contrast study which can identify the obstruction. Rapid surgical intervention is associated with a better outcome and increased survival. After correction, these children can present with feeding problems, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and increased risk of developing further surgical conditions. Paramedic professionals should therefore consider early transfer to hospital if asked to attend these children for a suspected ‘acute abdomen’.

Pyloric stenosis

Pyloric stenosis classically presents with projectile non-bilious vomiting in an infant showing a desperate intent to feed immediately after vomiting. The problem is caused by the thickening of the smooth circular layer of the pyloric muscle (at the junction between the stomach and first part of the small intestine), thus preventing adequate gastric emptying and leading to forceful vomiting. Pyloric stenosis can present between 2–12 weeks of age, with most cases seen between 5–7 weeks, and the condition again has a male preponderance (13 males: four females). The incidence is approximately two to four per 1000 live births with an increased incidence seen in first-born children (possibility of a genetic susceptibility). However, the actual aetiology remains unknown (Schecter et al 1997). Studies have reported an increased incidence of pyloric stenosis in formula-fed infants, but a definite association yet remains to be proven (Krogh et al, 2012).

The vomitus is non-bilious, usually contains milk (infant has recently fed) and as the condition progresses the infant is unable to maintain adequate nutritional status. This can manifest as persistent hunger, dehydration, failure to thrive, lethargy and poor urine output. Any or a combination of these should, therefore alert paramedic practitioners to the need to transfer the infant promptly to the emergency department.

On examination, sometimes a firm, non-tender mass in the right upper abdominal quadrant may be palpated, described as an olive-shaped mass (Thayalan et al 2013), though this requires an experienced clinician's hand.

The immediate management of pyloric stenosis involves correction of salt and water imbalance and to recoup fluid loss. An abdominal ultrasound scan is usually diagnostic and is currently the investigation of choice. The definitive treatment is a Ramstedt pyloromyotomy (Aspelund & Langer 2007), after which the infant generally starts to feed within 24 hours of the operation and most can be safely discharged home within 48 hours.A higher incidence of gastro-oesophageal reflux has been noted after the surgery, and carers may request for paramedic attendance if this worsens.

Appendicitis

Appendicitis is an inflammation of the vermiform appendix and is the most common abdominal surgical emergency occurring in older children (Alder et al, 2010). The exact cause remains unknown; however studies have suggested a relationship between viral diseases (for eample, influenza) and appendicitis (Alder et al 2010).

There is a classical triad of symptoms: fever, vomiting and right iliac fossa pain (though the abdominal pain often starts in the umbilical or epigastric region). Not all cases however present in this way, and it is important that paramedic professionals attending a child with abdominal pain also consider other non-specific symptoms such as loss of appetite, non-specific back pain and lethargy which may support a diagnosis of appendicitis. In particular, toddlers and young children usually do not present with the classical signs and symptoms, but may present with a distended abdomen, difficulty in walking, withholding faeces and discomfort while having their nappy changed (these activities cause exacerbation of pain). However, appendicitis is uncommon in children less than three years-of-age and accounts for only 2 % of all cases (Spence et al, 1998). It does, however, happen.

Appendicitis can quickly progress to peritonitis if it remains undiagnosed or can lead to abscess formation. Early transfer followed by an assessment by the paediatric/surgical team usually establishes the diagnosis in most cases. Radiological investigation in the form of an ultrasound scan may help, though this is not definitive in most cases and clinical acumen is by far the best diagnostic tool. The current treatment of choice is a laparoscopic removal of the inflamed appendix, although open surgical intervention may be needed in some cases. Some children may continue to complain about non-specific abdominal pain during the recovery period and paramedic teams may be asked to attend the child at home. Most cases may be managed with assessment, explanation and reassurance; however if there remains any suspicion of a post-operative complication, the child should be urgently transferred back to the hospital.

Testicular torsion

Testicular torsion in children can present with unilateral redness and swelling of the scrotum and acute testicular pain. Vomiting may be a cardinal sign in pre-verbal infants. Torsion of the testes is caused by a sudden rotation of testicle about its axis, leading to twisting of the spermatic cord (Gunther and Reuben, 2012). This sudden torsion can compromise blood flow to the testicle resulting in ischemic injury and infarction. Once this has occurred, the survival of the testicle is in jeopardy and time to surgery is of the upmost importance—every second counts.

Testicular torsion is usually an acute presentation, with a double peak incidence in children: neonatal period and early puberty.

The annual incidence in males under the age of 25 years is 1:400 (Pillai and Bresner, 1998). It is important to consider the diagnosis of testicular torsion in boys presenting with acute pain in the abdomen as they may not readily volunteer any information pertaining to their genitalia. Paramedic professionals may do a quick inspection (with consent) and this may point towards the diagnosis. On examination the presence of a discoloured, painful, swollen hemi-scrotum may be evident. The testes, should the child / young man be comfortable enough to allow you to examine it, may also be relatively ‘high riding’ within the scrotum due to the absence of the cremasteric reflex and a thickened, twisted spermatic cord (Davenport, 1996; Kadish and Bolte, 1998).

Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency and is known to cause irreversible damage to the testis if left untreated; any suspicion should therefore be followed by an urgent transfer. While doppler ultrasound (to demonstrate the lack of blood flow to the affected testes) can be diagnostic, time should never be wasted undertaking such investigations in a pre-hospital setting. All cases of a suspected testicular torsion should undergo explorative surgery as soon as possible to try to take advantage of the small window of time that exists between the torsion and the point where the ischaemic testes becomes unsalvageable (Gunther and Reuben, 2012).

Paramedic professionals can make a difference

Paramedic practitioners are often called to attend children with abdominal pain, loose stools or vomiting. It is important to remember that only minimal clinical intervention is usually necessary in the pre-hospital setting, as long the child is haemodynamically stable, and in most cases of a suspected surgical problem the definitive diagnosis can only be made in the hospital setting. Paramedics can, however, play a vital role not only in the detection of surgical pathologies in children, but also in supporting families and children during an ambulance transfer to specialist services, and in communicating vital information to receiving hospital teams to aid diagnosis and treatment.

The paramedic team's role is therefore integral to the successful outcome for this group of children:

Conclusions

Abdominal pain and other GI presentations as a result of underlying surgical problems are less common in children and can pose a diagnostic challenge as the signs and symptoms can be non-specific, especially in young infants. it is likely that a definitive diagnosis may not be made in the pre-hospital setting; however identification of risk factors and/or red flag symptoms will help in the identification of some surgical conditions and a prompt transfer to hospital may make all the difference to the outcome for the child. Any suspicion of a surgical condition should therefore be followed by a focused assessment and expedient transfer to specialist services.