As paramedicine has advanced and become more patient-focused, paramedics are increasingly referring patients to pathways and services other than the traditional emergency department route (Tohira et al, 2014; Oosterwold et al 2018). Using alternative pathways has inherent risks. One of the indicators of the efficacy and safety of the use of alternative pathways is the number and frequency of related future health events. Studies suggest that the numbers of future events following traditional and alternative pathways in well-governed systems are similar (Snooks et al, 2017). However, in a number of presentation types, such as falls, chronic disease exacerbations, and chronic illness, the risk of future events is significant, and ensuring both the implementation of appropriate pathways and engagement with those pathways is complex and challenging (Snooks et al, 2012; Comans et al, 2013).

Given this risk, an opportunity exists to assess both the likelihood of future events and the patient's resilience and capacity to cope in this eventuality. Additionally, the very process of engaging paramedic care for an unscheduled health event may be driven by patient resilience as patient decision making itself is complex and often relies on the individual's self-perception of coping and access to resources (Morgans, 2011; Booker, 2014).

Applying salutogenic approaches to prehospital care delivery

Salutogenesis is an approach to conceptualising wellness that examines health as a continuum and considers a multifactorial approach to determining an individual's health status (University West Centre on Salutogenesis, 2017). A salutogenic approach using the sense of coherence (SOC) theory predicts an individual's capacity to navigate current and future health events (Mittelmark and Bauer, 2017). This approach measures an individual's SOC, which is believed to be a determining factor in health resilience (Antonovsky, 1979; 1987; Giglio et al, 2015).

SOC is defined as ‘the extent to which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic, feeling of confidence that one's environment is predictable and that things will work out as well as can reasonably be expected’ (Antonovsky, 1987). It is, in essence, a combination of optimism and control.

A range of tools can be used to examine individuals' health resilience and health status in a salutogenic manner. However, no single tool that has the capacity to direct care professionals towards the optimum resources for an individual's unique situation that is appropriate to the prehospital environment can be identified in the literature.

The recent evolution of paramedicine has seen a focus on managing patient wellness in a more holistic way and developing a more patient-centred approach to practice. The profession is expanding with interest growing in non-traditional areas such as public health, primary healthcare (O'Meara et al, 2007), health promotion and disease prevention (Agarwal et al, 2015). Globally, paramedics are working to manage the health of populations as a method to both manage ambulance demands and improve health outcomes by encouraging more appropriate healthcare resource use.

Paramedics have traditionally worked in a pathogenic paradigm that seeks to respond to acute clinical needs. However, increasingly, expanded scope of practice models are being implemented to meet community needs (O'Meara et al, 2007). In many cases, patients requiring an ambulance have a range of health issues beyond acute ill health and injury (Woollard, 2015).

These health issues have been found to be more easily identified and managed within a salutogenic model, which considers a range of factors and influences over the health of the individual (Mittelmark and Bull, 2013), than when using the traditional model of care. Poor health has been shown to reduce wellbeing while high levels of wellbeing have been shown to reduce impairment resulting from poor physical health (Barley and Lawson, 2016).

While there are many tools to assess pathogenic issues in patients, few measure areas such as resilience and the capacity to engage resources to address health events. This overview examines the literature regarding aspects of salutogenic and SOC theories and psychometric tests available, with the aim of determining whether there is a tool suitable for the prehospital environment and the potential value of such a tool.

Sense of coherence along the health continuum

Antonovsky (1993) determined that the origins of health were found in an individual's SOC and general resistance resources (GRRs), which are resources available to that person to support resilience and will be discussed in more detail.

Antonovsky suggested it was productive to focus on what he determined to be ‘a problem with active adaptation to inevitable environmental stressors’ (Antonovsky 1987; Vinje et al, 2017).

SOC is comprised of three core elements:

Comprehensibility

Comprehensibility refers to the individual's understanding of the stressor and the belief that specific acts or behaviours will lead to various outcomes (Antonovsky, 1987). This concerns a person's ability to judge reality rather than focusing solely on emotions.

Manageability

The second element, manageability, relates to an individual's ability to see the resources that are at their disposal and use those to manage the stressor effectively. According to Antonovsky (1987), a person with a weak SOC will lack either the GRRs necessary or the ability to draw on their GRRs to perceive the stressor as manageable.

Meaningfulness

Finally, meaningfulness refers to an individual's ability to see purpose in overcoming the stressor and to view investing their time or energy into this as worthwhile (Antonovsky, 1987).

Antonovsky's concept of breakdown

Antonovsky termed the movement towards the ‘dis-ease’ end of the health continuum as ‘breakdown’. The health continuum, as Antonovsky (1987) suggested, has four dimensions in which people experience varying degrees of breakdown. The first dimension rates a person's experience of pain, while the second dimension rates their experience of functional limitation. The third and fourth dimensions rate the ‘prognostic implication’, or how the health impact would be defined clinically by a health professional, and the ‘action implication’, or what actions would be required to address the situation and impact on health and wellness respectively (Antonovsky 1987).

Mittelmark and Bull (2013) highlight four key issues regarding Antonovsky's concept of health. First, his construct is not a true continuum but a categorisation. Second, to be at the ‘ease’ end of the continuum, one must not be experiencing any pain and distress. Third, Antonovsky regarded the ease/dis-ease continuum of breakdown as only one aspect of wellbeing. Finally, his measure of health is simply not practical in health promotion research (Mittelmark and Bull, 2013).

While Antonovsky's concept of health breakdown is not suitable for health promotion, the concept of breakdown along a continuum should not be disregarded. A plethora of instruments to measure dis-ease already exist; Antonovsky's concept of health breakdown adds an interesting dimension of individual experiences within the pathogenic construct.

General resistance resources

GRRs are anything an individual can draw on during stressful events. Resources may be anything—material, biological, emotional, physical or existential—or any meaningful activities or rituals (Antonovsky, 1987). Antonovsky hypothesised that GRRs provided a moderating effect to the stressors that impact an individual's health, but the key is in the person's ability to recognise their own resources and to draw on them during stressful events (Antonovsky, 1987). This ability to recognise and draw on GRRs is contingent upon one's SOC.

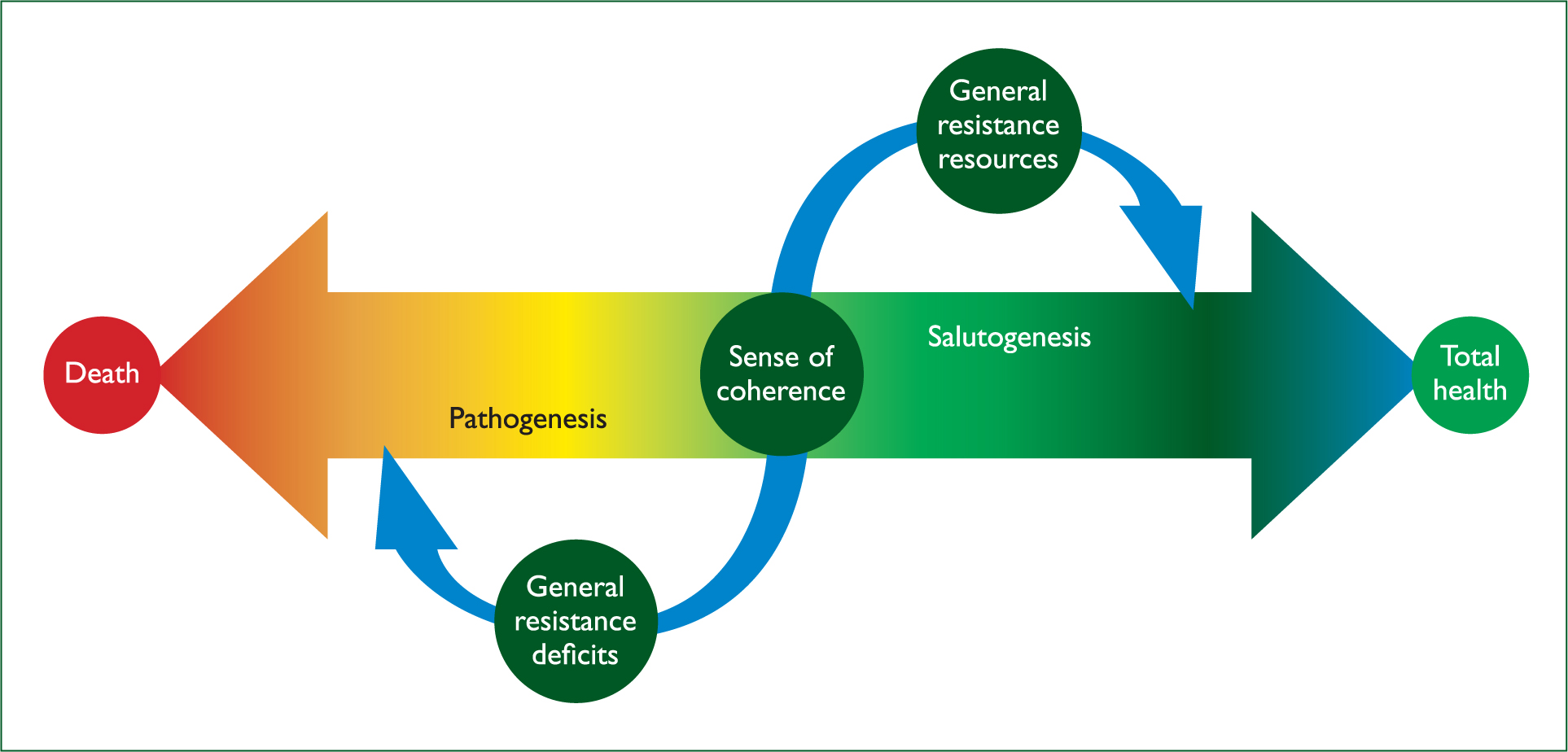

Incorporating both stressors and GRRs into the health model, Antonovsky merged the concept, viewing GRRs and general resistance deficits (the lack of GRRs) on a continuum (Idan et al, 2017) (Figure 1).

People on the high end of the continuum tended to be engaged in decision-making and showed consistent, balanced life experiences. Likewise, those on the high end of the continuum were viewed to have more GRRs at their disposal, which meant they could adapt better to stressful events. On the other end of the continuum, however, individuals participated less in decision-making, displayed inconsistent life experiences and tended to be deficient in resources (Idan et al, 2017).

Methods

An overview of literature was conducted to establish whether any salutogenic theory or salutogenic tools were being applied to paramedic practice. A search strategy was developed that adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al, 2015).

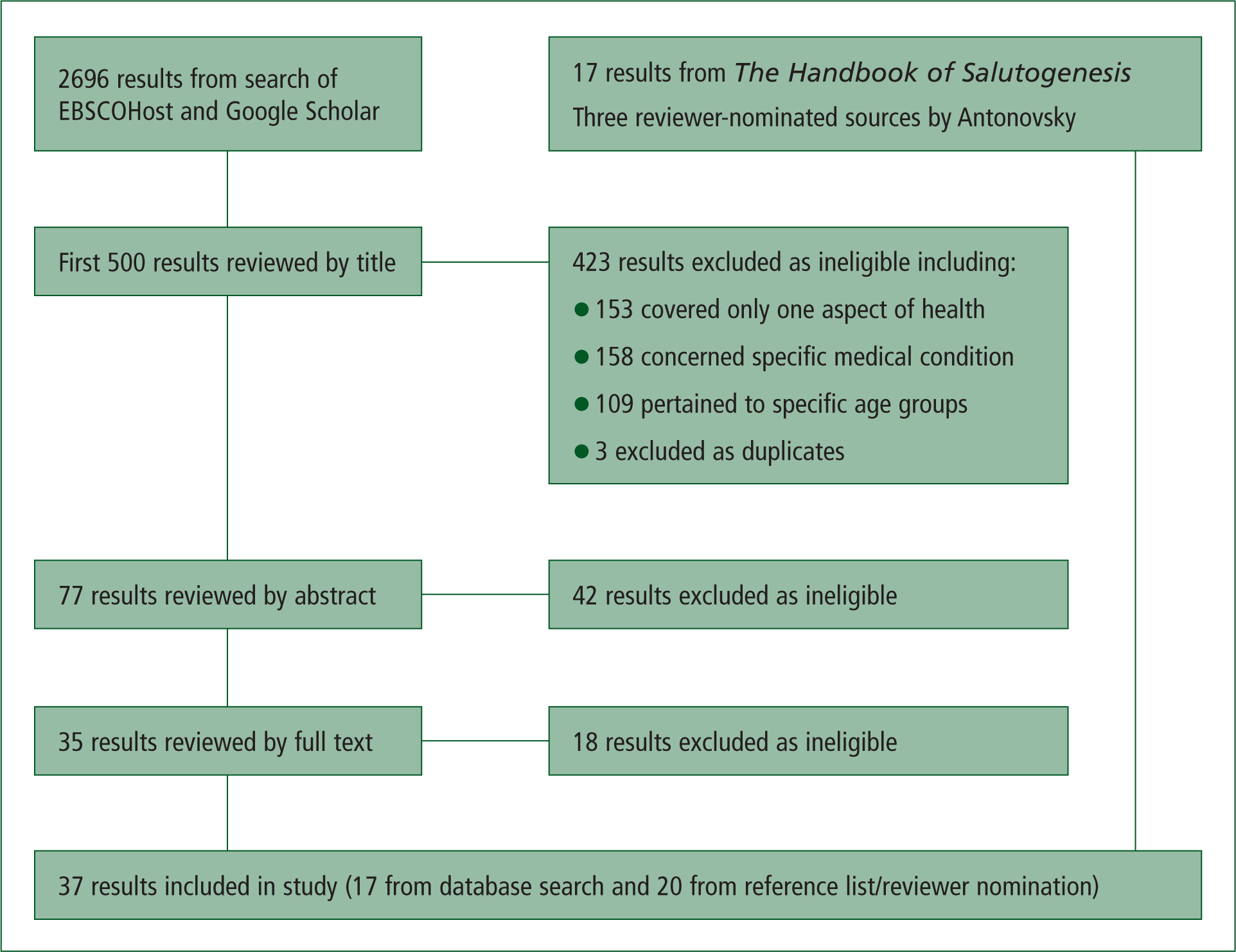

This overview used a database search using EBSCOHost (which includes CINAHL, Health Source, PsychINFO, SocINDEX, and MEDLINE) as well as Google Scholar to pick up a wide range of publications and grey literature. Also included were an additional 20 sources, comprising 17 references from the Handbook of Salutogenesis (Mittelmark et al, 2017a) and Antonovsky's three principal monographs (1979; 1987; 1993). Older publications examining salutogenic and SOC theory were identified and included, as recent publications tended to focus on specific populations rather than being generalisable to the whole population.

The search was undertaken using the following search parameters: ‘sense of coherence’ OR ‘psychometric propert*’ AND ‘measur*’ AND ‘valid*’.

The initial search using ESBCOHost and Google Scholar yielded 2696 publications. The first 500 titles were reviewed as the remainder of the articles were principally duplicates. Exclusion and inclusion criteria were determined to ensure a systematic approach was taken to publication selection (Figure 2). Exclusion criteria included publications dealing with individual health conditions, individual elements of health or with specific age groups only. Studies validating translated versions of the original psychometric tests were also excluded. Following the review process, 17 titles were chosen as well as the additional 20 mentioned.

Results

Orientation to Life Questionnaire

Antonovsky viewed life as ever changing; it created challenges, and an individual would develop strategies and use resources to cope with these in everyday life (Eriksson, 2017). Antonovsky hypothesised that a person's SOC could be measured using the Orientation to Life questionnaire (OtLQ) and people found to have a high SOC were better able to identify and use the resources available to them, leading to better health outcomes than people with a weak SOC. Antonovsky also argued that a person's SOC was not fixed but could be strengthened or weakened by stressful events and the resources available to them (Antonovsky, 1987).

The OtLQ was developed as a means of measuring an individual's SOC by assessing the three core components of comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness. The original scale consisted of 29 questions (SOC–29); Antonovsky later developed a shorter version (SOC–13), derived from the original (Antonovsky, 1987). The SOC–29 and the SOC–13 have been used in at least 48 countries across a range of population groups of varying ages and ethnicities (Eriksson and Mittelmark, 2017). Antonovsky maintained that one should avoid examining individual dimensions as all three dimensions constantly interact with each other (Antonovsky, 1987). However, more recent research suggests that SOC is multidimensional, with each dimension having separate properties yet still interacting (Eriksson and Mittelmark, 2017).

While both the SOC–13 and SOC–29 have been validated in a wide range of studies, there have been discrepancies between their results and other instruments that measure health, self-perceptions, quality of life, stressors, attitudes, behaviours and wellbeing (Eriksson and Lindström, 2005). Additionally, shorter versions of the OtLQ have been developed, some with as few as three questions, indicating there is a need for health questionnaires to be relatively short.

Antonovsky maintained that SOC developed until approximately the age of 30 then stabilised until the age of retirement, at which point it decreased (Antonovsky, 1987). Subsequent research, however, does not support this. While SOC does appear to develop over time, it has been shown to be shaped by experiences, weakening and strengthening with each life challenge (Eriksson and Mittelmark, 2017). Antonovsky argued that experiences in various situations developed a sense of consistency or predictability and that predictability led to a stability in SOC; therefore, many questions of the OtLQ refer to predictability. Flensborg-Madsen et al (2006a; 2006b), however, felt that predictability was a poor indicator of measuring health and should not be included in measuring SOC.

Assessment tools

A range of assessment tools were found in the literature, some directly linked to Antonovsky's work and others measuring similar elements of patient resilience or functionality from similar theoretical approaches. The most comprehensive and validated tool was Antonovsky's OtLQ (Eriksson and Mittelmark, 2017). However, a number of other tools address key elements of the salutogenic approach.

The General Functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device measures the capacity of a family to engage in key coping functions. This includes the capacity of the family to support members and have a meaningful family dynamic (Boterhoven de Haan et al, 2015). De La Rosa et al (2016) explored the Response to Stressful Events Scale (RSES–22) and, from this, developed a four-question resilience test (RSES–4). While both scales showed promise in measuring responses to events and coping strategies, they primarily describe behaviour rather than address the additional capacity to believe or value outcomes of coping mechanisms; however, a few questions in the RSES–22 do touch on meaning.

Góngoro and Catro Selando (2015) examine a number of tools based on Authentic Happiness Theory, a similar theory of wellness. These include the Three Pathways to Well-being scale, the Meaning in Life Questionnaire, the Satisfaction With Life Scale and the Personal Wellbeing Index (Góngoro and Catro Selando, 2015). These scales address meaningfulness but are less focused on the capacity to engage resources and are more retrospective than prospective. In a similar vein, Huppert and So (2013) and Hone et al (2014) explore Flourishing Theory and the associated Flourishing Scale. This scale is also focused on psychological wellbeing and is less effectively applied to health holistically.

Several scales have been developed based on Antonovsky's work. Flensborg-Madsen et al (2005a) concluded that SOC had only a weak-to-moderate correlation with measures of physical health. This led Flensborg-Madsen et al (2005b) to develop an alternative assessment that did not measure predictability but included additional questions; it is known as the SOC II.

Preventative health models

Selective Optimization with Compensation

The Selective Optimization with Compensation Model (SOC-model) has been shown to be a leading model for successful ageing, focusing on adaptive coping in a proactive and preventative manner by using resources for compensation processes (Diener et al, 1987; International Well-Being Group, 2006; Steger et al, 2006; Ouwehand et al, 2007). While the model varies from Antonovsky's in its approaches to successful ageing, the theoretical underpinnings of the two approaches are similar.

Health Development Model

Antonovsky suggests that salutogenesis and pathogenesis are separate yet complementary concepts, useful in characterising human experiences of illness and health (Mittelmark et al, 2017b). The Health Development Model (HDM) also uses key concepts in which salutogenesis and pathogenesis are complementary to one another.

The HDM was originally intended to be a framework for the development of research indicators monitoring the effects of health promotion interventions (Bauer et al, 2006). The HDM incorporates both pathogenic and salutogenic orientations, highlighting the relationship between disease prevention and health promotion (Mittelmark et al, 2017).

The HDM, however, does not incorporate SOC. The developers of the HDM intentionally chose to leave positive health outside the agenda of the healthcare system, the ill-health side of the HDM, instead aligning the positive health concept with salutogenic thinking on the health promotion side of the model (Mittelmark et al, 2017). This has become a key barrier to overcome within contemporary healthcare systems. There have been frequent discussions regarding which care providers should be responsible for preventive health and positive health measures, with the task often directed to primary care providers (Parker, 2013).

Person-centred integrative diagnosis

Person-centred integrative diagnosis (PID) considers that wellbeing should be viewed as a multifactorial complex adaptive system which is influenced by a range of distinct processes (Cloninger et al, 2012). These components include health status, experience of health and contributors to health. Health status refers to a person's functioning or wellness as opposed to disability or disorder. A person's experience of health refers to their own self-awareness as opposed to their distress or misunderstanding. Finally, contributors of health refer to an individual's protective factors as opposed to their risk factors. The elements of PID align with the components of SOC theory and are also used for examining psychological maturity, flourishing and resilience (Cloninger et al, 2012).

Discussion

Development of an assessment tool

Given the potential value of SOC theory in assessing wellness in the population, there is a need to develop a tool that would allow prehospital practitioners to assess an individual's SOC and GRRs to identify not only areas where the person may need additional assistance, but also any strengths that may assist the person in coping with their health event. This would allow healthcare providers to provide a more comprehensive approach to addressing health issues.

Additionally, identifying weak areas of an individual's SOC would provide the health professional with greater clarity over which pathways to take to better address the person's needs and, ultimately, improve their health resilience. Such a tool would have potential impacts not only on the day-to-day care of patients in a prehospital environment, but also in better addressing key demand management areas such as frequent users and populations with high burdens of chronic disease.

In Antonovsky's OtLQ, participants selected responses on a rating scale from 1 to 7 with questions using both positive and negative language (Antonovsky, 1987). However, when this method was tested using Rasch analysis, it was found to create a level of difficulty that resulted in some responses not being completed (Holmefur et al, 2015). Holmefur et al (2015) discovered that collapsing the scale to a five-point rating provided optimal results.

Responses to the assessment tool should be designed to fit a range of levels across the health continuum. Each response should be assigned a score or measurement that would accurately reflect the individual's location on the continuum at that point in time (Kostoglou and Pidgeon, 2016).

Questions within the assessment tool should be designed to measure individuals' resilience. Responses to the questions should display a range from resilient behaviours to depressive symptoms. Studies show that individuals who selected responses displaying optimism were more likely to return to their baseline state or better following adverse events (Smith et al, 2008; Huppert and So, 2013; Bucci et al, 2016; De La Rosa et al, 2016; Ni et al, 2016).

It is also suggested that the assessment is designed to determine the individual's ability to recognise and use internal and external resources available to them. Intangible assets such as relationships, spirituality and religiosity have been shown to strengthen SOC and improve quality of life and wellbeing (Skevington, 2004; von Humboldt and Leal, 2015; Kern et al, 2016).

Additionally, the assessment tool should be designed to measure the extent to which one sees their life as having purpose or meaning. The questions within the assessment should seek the individual's perceptions of their daily activities, relationships with those important to them and previous life experiences (Su et al, 2014; Hone et al, 2014; Boterhoven de Haan et al, 2015; Góngora and Castro Solano, 2015).

Benefits of assessing SOC and general resistance resource in prehospital care

A range of tools can be used to help health professionals assess various aspects of an individual's health, SOC and resilience; however, it is often challenging to identify precisely which assessments to conduct. This assessment tool could be incorporated into an electronic application so the assessment could be conducted quickly and easily and direct health professionals to more specific health assessments. This would entail incorporating aspects of health and wellness in a manner that engenders self-efficacy, quality of life, wellbeing and more.

An assessment tool to determine patient SOC and GRRs would be useful in primary care settings such as community paramedicine, nursing and other areas where care planning is a critical part of the patient interaction. In the prehospital environment, this type of tool would be useful in directing the care provider to referral pathways to address patient needs using a patient-centred approach.

By assessing patient SOC and GRRs, prehospital care providers would be able to identify the weaker components of the patient's SOC. Strategies could then be implemented to address those deficits. Additionally, prehospital health professionals would be able to identify the unique GRRs of the individual and link these to resources to assist the person with overcoming the health event.

Conclusion

By taking a multifactorial approach to determining a person's health status and predicating their capacity for adaptive coping, health professionals will better be able to assist patients/clients in overcoming health events and build health resilience to improve future health outcomes.

There is a need to develop a tool that is conducive to the prehospital environment that could direct health professionals towards the most appropriate resources for everyone's unique situation. Developing and implementing a tool to assess patients' SOC and GRRs would allow health professionals to take a more salutogenic approach to addressing healthcare needs while remaining focused on current health events.