Investigations into the trauma patient who suddenly deteriorates while in the care of a paramedic crew, either on scene or during transport to hospital, is limited. There is no evidence-based guide identifying the categories of trauma patients who are more likely to deteriorate suddenly in the presence of paramedics. Nor is it clear what the appropriate triage options should be for those patients: transport to a Level 1 trauma centre or diversion to the closest hospital.

Previous trauma-related studies have investigated such issues as scene times (Feero et al, 1995; Goodacre et al, 1997; Eckstein and Alo, 1999; Altintas and Bilir, 2001; Al-Ghamdi, 2002; Birk and Henriksen, 2002; Carr et al, 2006; Gonzalez et al, 2008; Gonzalez et al, 2009); total out-of-hospital time (Feero et al, 1995; Al-Ghamdi, 2002; Carr et al, 2006; Newgard et al, 2010; Osterwalder, 2002); out-of-hospital time, and effect on mortality (Osterwalder, 2002; Newgard et al, 2010), and the effectiveness of treating trauma patients in Level 1 trauma centres (Cooper et al, 1998; Freeman et al, 2006; MacKenzie et al, 2006; Nirula and Brasel, 2006; Papa et al, 2006).

However, there is a paucity of scientific literature investigating the trauma patient who suddenly deteriorates in the prehospital setting. The evidence available is a retrospective cohort study by Boyle et al (2008a) and the other, a case study by Nadel et al (1997). As demonstrated by the two studies identified, there is a lack of high-level, i.e. randomized controlled, studies available.

Therefore, the objective of the study is to determine the incidence, physiological criteria for sudden deterioration, and outcome of trauma patients who suddenly deteriorated during paramedic care.

Methodology

Study design

This is a secondary data analysis of an existing state-wide prehospital-based trauma dataset.

Setting

The data was collected in Victoria, a south-eastern state of Australia. Victoria covers approximately 227 590 square kilometres. At the time of the study, it had a population of approximately 4.9 million people (49% males and 51% females) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2002).

At the time, there were two ambulance services in Victoria, the Metropolitan Ambulance Service (MAS), and Rural Ambulance Victoria (RAV), which have since amalgamated to form once service, Ambulance Victoria. The MAS provided the ambulance service for the Melbourne metropolitan area, which covered 7694 square kilometres, with a population of approximately 3.5 million people at the time (Metropolitan Ambulance Service, 2002). RAV provided the ambulance service for rural Victoria with a population of 1.4 million people over an area of approximately 219 896 square kilometres (Rural Ambulance Victoria, 2002).

There is a two-tier ambulance response available in Victoria. The first tier being the ambulance paramedic with core advanced life support (ALS) skills. The second tier is the mobile intensive care ambulance (MICA) paramedic who has a greater range of ALS skills including intubation, cardioversion, and a greater range of drugs.

Population

Patients were included in the original data collection if they had sustained a traumatic injury and were transported by emergency ambulance in Victoria from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2002.

The database of patients who suddenly deteriorated consisted of all patients who had sustained trauma from any cause, were transported by the ambulance service, and who suddenly deteriorated in the presence of paramedics either at the scene or enroute to hospital.

The sudden deterioration database did not contain patient data if the patient was being transported between hospitals (inter-hospital transfer), if there was a lack of information on the patient care record (PCR) to establish the reason for the patient suddenly deteriorating, or if the trauma type was inadequately documented (e.g. blunt, penetrating, minor), and the patient did not suddenly deteriorate either at the scene or enroute to hospital.

Definitions

Sudden deterioration

As there is no internationally recognized definition of sudden deterioration in prehospital trauma management, sudden deterioration for the study was defined as:

‘A decrease in any of the physiological status components from the last recorded observations to the most recent. This deterioration is in light of on-going management of the patient's overall condition. This timeframe between the observations would normally be about fifteen minutes’

The physiological criteria for sudden deterioration were:

Other definitions

Procedures

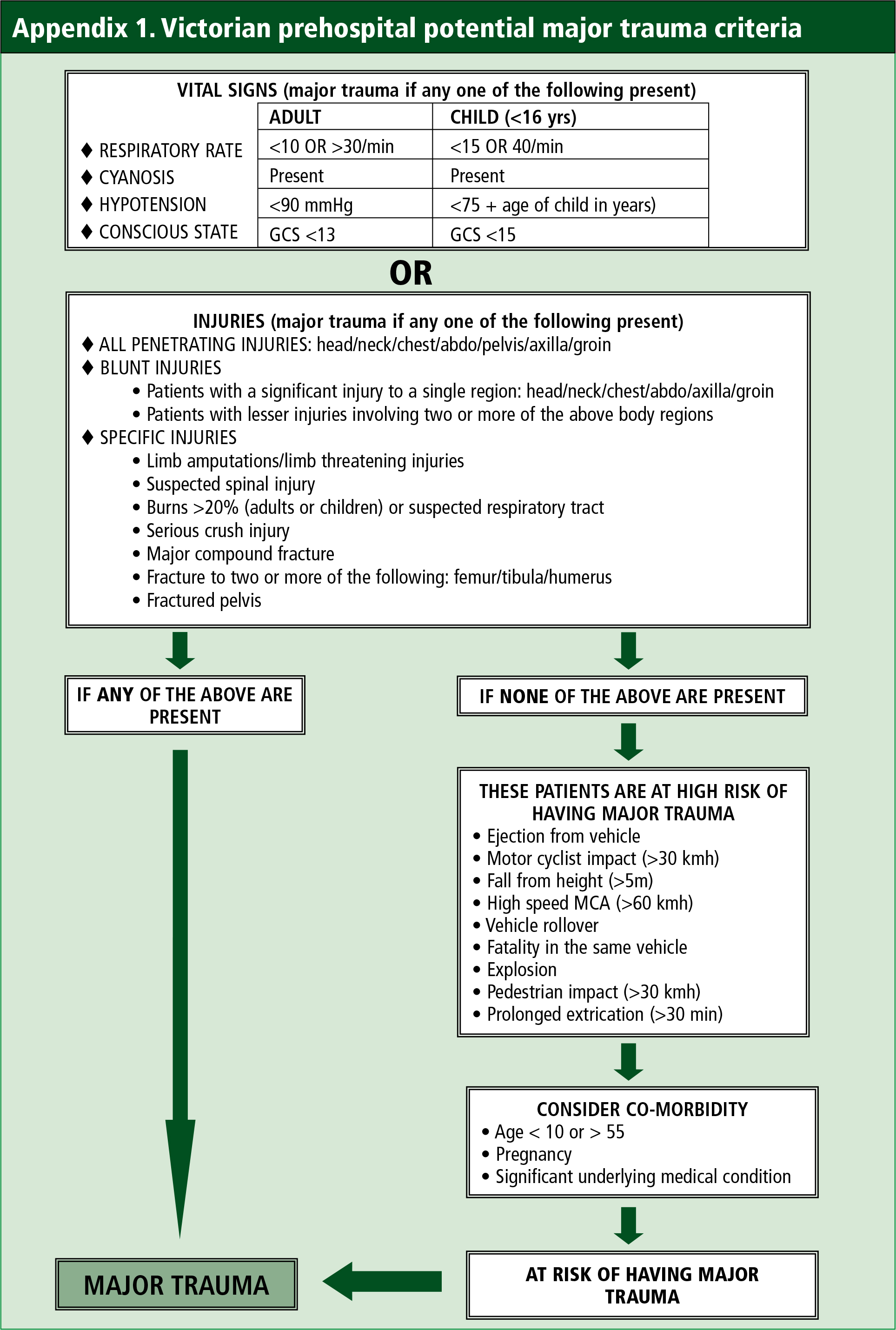

The sudden deterioration dataset had been created previously by linking twelve months of ambulance trauma data (2002) with the Victorian State Trauma Registry (VSTR) (Boyle, 2008). The VSTR contains the prehospital, hospital, and outcome data for patients who meet the major trauma criteria for Victoria (Table 1).

| Death after injury |

| Admission to an intensive care unit for more than 24 hours, requiring mechanical ventilation |

| Urgent surgery for intracranial, intra-thoracic, or intra-abdominal injury, or for fixation of pelvic or spinal fractures |

| Injury severity score (ISS) >15 |

| Serious injury to two or more body systems (excluding integumentary). |

The sudden deterioration dataset was interrogated using the sudden deterioration criteria, defined above, to identify patients who suddenly deteriorated in the presence of paramedics, either on scene or enroute to hospital.

Transport mode

Patients were transported by road ambulance, helicopter ambulance, or both. There has been no distinction made between the mode of transport as the objective of the study was to investigate the incidence, physiological criteria for sudden deterioration, and outcome of the patients.

Outcome measures

The outcomes measures investigated were:

Data analysis

Descriptive data analysis was undertaken using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19.0.0.1, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic data. A student's T-test was used to compare the difference in injury severity score (ISS) between metropolitan and rural patients. All confidence intervals (CI) are 95%.

Ethics

Ethics approval for the project was obtained from the Monash University Standing Committee for Ethics in Research.

Results

Prehospital aspects

There were 239 patients who met the criteria for sudden deterioration, which amounts to 0.45% of the total number of trauma patients (n=53 039) (Boyle et al, 2008b) transported or seen by the Victorian ambulance service for 2002. The MAS attended to 58% while RAV attended to 42% of the patients who suddenly deteriorated. The mechanism of injury type and the number attended by each ambulance service are listed in Table 2. The trauma mechanism of injury criteria are from the Ambulance Service Victoria Time Critical Guidelines (Department of Human Services, 1999), used to categorize the data following data collection.

| Mechanism of injury type | MAS* | RAV* |

|---|---|---|

| No mechanism of injury | 98 | 39 |

| MCA >60 km/hr | 14 | 26 |

| Pedestrian struck >30 km/hr | 12 | 1 |

| Patient ejected from vehicle | 2 | 1 |

| Patient in vehicle rollover | 2 | 7 |

| Death of other vehicle occupant | 0 | 3 |

| Fall >5m | 0 | 2 |

| Object falling >5m | 0 | 1 |

| Motor cyclist/cyclist | 4 | 15 |

| Explosion | 0 | 0 |

| Patient trapped > 30 minutes | 7 | 5 |

MAS = Metropolitan Ambulance Service; RAV = Rural Ambulance Victoria

There were 66% males and 34% females with a mean age of 35.3 years, standard deviation of 19.7 years. The median age was 30 years with a range of 1 to 88 years. The age reporting used the actual age when there was a date of birth known, and approximate age (normally a guess by the paramedic) when there was no date of birth available.

The patients were further categorized into paediatric, adult and elderly for international comparison. For these groups, 10.2% were paediatric (<15 years), 16.9% of patients were elderly (>55 years), 72.9% were in the adult group, the remainder had no age recorded on the PCR. The presenting signs of sudden deterioration can be seen in Table 3.

| Deterioration type | N (239) | % of total sudden deterioration |

|---|---|---|

| Sudden decrease in GCS >2 points or a GCS Score <13 | 58 | 24.3 |

| Cardiorespiratory arrest | 6 | 2.5 |

| Sudden drop of BP and sudden decrease in GCS ≥ 2 points | 22 | 9.2 |

| Sudden increase/decrease in pulse rate and sudden drop of BP and sudden decrease in GCS ≥2 points | 6 | 2.5 |

| Sudden Increase/decrease in pulse rate and sudden decrease in GCS ≥2 points | 8 | 3.3 |

| Sudden increase/decrease in pulse and resp rate and sudden drop of BP | 1 | 0.4 |

| Adult BP <90 mmHg | 130 | 54.4 |

| Paediatric BP <75 + age in years | 8 | 3.3. |

Trauma types

The outcomes for the different trauma types, blunt trauma, penetrating trauma and specific trauma types are shown in Tables 4, 5 and 6. The outcomes include prehospital potential major trauma (Appendix 1), hospital defined major trauma (Table 1), and died.

| Blunt trauma | Prehospital potential major trauma | Hospital defined major trauma | Died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head/neck | 106 | 39 | 11 |

| Thorax | 27 | 13 | 3 |

| Abdomen | 24 | 10 | 6 |

| Pelvis | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Axilla | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Groin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Specific trauma types | Prehospital potential major trauma | Hospital defined major trauma | Died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected spinal injury | 15 | 6 | 2 |

| Fractured pelvis | 15 | 9 | 2 |

| Burns > 20% + respiratory tract | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Limb amputation | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fracture of 2 or more long bones | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Serious crush injury | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Penetrating trauma | Prehospital potential major trauma | Hospital defined major trauma | Died |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head/neck | 25 | 14 | 5 |

| Thorax | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Abdomen | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Pelvis | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Axilla | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Groin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

There were four patients who suddenly deteriorated that did not have prehospital potential major trauma, see Appendix 1 for a definition of prehospital potential major trauma.

Patient times

There were n=204 (85.4%) records with data to determine the scene time for patients who suddenly deteriorated. For MAS there were n=133 (95.7%) records available, with n=71 (71.0%) RAV records available (Table 7). For all non-trapped patients, there were n=194 (85.5%) records available. For MAS, there were n=127 (85.5%) records available, with n=67 (70.5%) RAV records available (Table 8). For all trapped patients, there were n=10 (83.3%) records available. For MAS, there were n=6 (85.7%) records available with n=4 (80.0%) RAV records available (Table 9).

The transport time was available for n=210 (87.9%) of incidents. For MAS, the transport time was available for n=130 (93.5%); with RAV, the transport time was available for n=80 (80.0%) of incidents (Table 10).

If we use the call received time as a surrogate for the time of the trauma incident, as we do not have the actual incident time, the number of incidents available for the time of incident to hospital analysis is n=149 (62.3%). In MAS, the incident to hospital time was available for n=123 (88.5%) and for RAV n=26 (26%) of incidents (Table 11). Due to discrepancies in the data, i.e. missing times, not all information is available for each of the time intervals outlined above.

Hospital aspects

There were n=52 patients who required ventilation for more than 24 hours in an intensive care unit (ICU). A total of n=36 patients required urgent surgery within 24 hours of admission. There were n=32 patients who died following admission to hospital. For patients admitted to hospital, the mean ISS score was 33.62, CI 30.08 to 37.15, median score 32, and ISS range 4 to 75. There was ISS data for n=81 (33.9%) of patients. Of the patients who died, a greater percentage had an ISS of 25 to 26 and 54 to 75, the remaining deaths were scattered amongst the ISS scores > 15.

Of all the patients, n=112 (45.9%) were initially transported to one of the three major trauma services (MTS), with n=17 (7.1%) patients transported to one of the regional trauma services (RTS). The remaining patients were transported to other level hospitals within the state trauma system. There were four patients transported to a neighbouring state that has a large regional hospital just over the state border.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated that the number of patients who suddenly deteriorate because of a traumatic incident in the presence of paramedics, either on scene or enroute to hospital, is small. There is also a paucity of evidence describing the paramedic response to these suddenly deteriorating patients, i.e. does the paramedic transport the patient to the closest hospital, even though it may not be a major trauma service (MTS).

Demographics

The gender distribution for trauma patients who suddenly deteriorated is similar, 66% in this study compared to 62% in the state-wide trauma study for males, and 34% in this study compared to 37% in the state-wide trauma study for females (Boyle et al, 2008b). The mean age in this study, 35.3 years, was similar to that in the state-wide trauma study, 33.6 years, with the median age the same 30 years (Boyle et al, 2008b). The age range of 1 to 88 years in this study is close to the state-wide trauma study of 3 months to 99 years (Boyle et al, 2008b).

When looking at the age groups, paediatric, adult and elderly, the distribution in this study was similar to that in the state-wide study—10.2 to 14% for paediatric, 72.9 to 70% for adult, and 16.9 to 16% for elderly (Boyle et al, 2008b). The lack of significant variation in gender and age distribution for this study suggests that this sub-group of trauma patients is a representative sample of the total trauma cohort identified in the state-wide trauma study (Boyle et al, 2008b).

Trauma distribution

The distribution of sudden deterioration trauma, metropolitan (MAS) vs rural (RAV), in this study was significantly different to that in the state-wide trauma study. In this study, 58% of the sudden deterioration trauma was in the metropolitan area with 42% in the rural area, compared to 72% metropolitan and 28% rural in the state-wide trauma study (Boyle et al, 2008b).

In percentage terms, more patients suddenly deteriorated in the rural setting compared to the metropolitan for motor vehicle accidents and motor cycle/cycle accidents. This could be attributed to higher speed accidents in rural areas compared to the metropolitan region and the distance to hospitals with appropriate interventional services. The percentage of patients trapped >30 minutes was the same for both metropolitan and rural settings.

The only mechanism of injury type significantly higher in the metropolitan area compared to the rural area was pedestrians struck >30 km/hr. This is probably due to the increased number of people crossing roads in busy traffic areas in the metropolitan area compared to rural towns.

A commonly used measure of injury severity in the international literature is the injury severity score (Baker et al, 1974), with a score >15 being considered as major trauma. The ISS was available for 74 patients with 31 patients from RAV and 43 from MAS having an ISS >15. There was no statistically significant difference (P=0.196) between ISS for patients in metropolitan and rural locations.

Scene times

From 1992 until 2005 the Consultative Committee on Road Traffic Fatalities (CCRTF) in Victoria undertook a retrospective analysis of ambulance and hospital data to determine if a death following a road accident, after an ambulance arrived, was potentially preventable (McDermott et al, 1994—1999; 2003; 2006). One of the main prehospital errors identified in all reports was a scene time >20 minutes; however, there was no comment about the crew waiting for road accident rescue crews or a second ambulance as the cause for the prolonged scene time. Therefore, the scene time, transport time and total incident time were analyzed to ascertain if ambulance crews were spending too long at the scene, transporting the patient to distant hospitals, and whether the patient was in a receiving facility within as short a timeframe as possible, given the patient's deteriorating condition.

Rural trauma scene times are often affected by a delay in resources arriving. This is normally due to distances and the type of staff available, especially for support services, e.g. road accident rescue crews, as they are predominately volunteers, and awaiting additional ambulance resources, something none of the studies to date have investigated. A pilot study investigating increased scene times for rural trauma accidents by Boyle and O'Meara (2008) identified the main reasons for scene time delay were ambulance crews waiting for road accident rescue crews to arrive and then extracting the patient.

Another reason for prolonged scene times may also be attributed to advanced life support (ALS) procedures being attempted at the scene. Increased scene times due to ALS procedures has been identified in several studies (Donovan et al, 1989; Birk and Henriksen, 2002; Kelly and Currell, 2002), however, several other studies suggest that increased scene time may increase patient mortality (Feero et al, 1995; Gonzalez et al, 2008; Gonzalez et al, 2009). Furthermore, this is contradicted by Newgard et al (2010) who suggests that decreased out-of-hospital time for patients with physiological deficit does not decrease hospital mortality rates.

Prehospital potential major trauma identification

Of some concern are the four patients who suddenly deteriorated but did not meet the criteria for prehospital potential major trauma (Department of Human Services, 1999). Two patients were from the RAV and two from the MAS area of operations. Three of the patients had minor trauma, one from a motor vehicle accident, and one had a fall from < 5 metres. All patients were adults with ages ranging from 21 years to 54 years.

Where relevant time intervals were available, two of the patients were at hospital within approximately one hour of the trauma incident. All patients had a drop in conscious state of at least 2 points in one of the three components or their GCS total fell below 13. This would suggest that the prehospital triage criteria for some patients who have only minor trauma may not be sufficiently sensitive to pick up the potential for this group of patients who suddenly deteriorate. Further work needs to be undertaken in a prospective study to better identify this sub-group of patients.

Incident to hospital time

The mean surrogate incident time to admission to hospital time suggests that trauma patients who suddenly deteriorate are in a metropolitan major trauma service (MTS) or a regional trauma service (RTS) in approximately an hour 50% of the time.

When looking at metropolitan results, this study had a mean hospital admission time of 55.2 minutes compared to two studies from the US where there was some difference, 47.5 minutes in a study by Feero et al (1995) and in a metaanalysis study by Carr et al (2006), 29.3 minutes for patients with an unexpected death and 30.96 minutes for other trauma patients. A study by Al-Ghamdi (2002) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, found that the mean total incident time for motor vehicle accidents was 34.6 minutes.

When looking at rural times, Carr et al (2006) found the mean total incident time was 43.17 minutes, where in this study it was 101.38 minutes. The overall incident time would suggest that the larger the geographical area covered by the ambulance service the greater the total incident time. In this study, the total incident time includes some primary response helicopter trips from rural locations to a MTS.

It would appear that a reduced out-of-hospital time for trauma patients does not affect their overall survival outcome. The ‘golden hour’ concept lacks any scientific evidence as outlined by Lerner and Moscati (2001), with Newgard et al (2010) finding a decreased out-of-hospital time for patients with physiological distress did not increase hospital mortality rates, and Osterwalder (2002) identifying out-of-hospital times for blunt polytrauma patients exceeding 60 minutes did not affect hospital mortality rates.

Transportation to a MTS

The state-wide trauma study identified that the trauma workload per paramedic crew was low, especially in some of the more remote rural areas (Boyle et al, 2008b). This low exposure to trauma patients may affect the decision-making and confidence of paramedics to transport the patient a longer distance to a higher level trauma hospital.

This study has identified very few trauma patients that suddenly deteriorate in the presence of paramedics. It was not possible to identify if ambulance crews diverted to the closest hospital for resuscitation of the trauma patient. Given the findings from this study and in the studies by Newgard et al (2010) and Osterwalder (2002), time of the incident to hospitalization can exceed the 60 minute time frame, when transporting the patient to the highest level trauma service available, with little affect on outcome, specifically mortality. Paramedics in Victorian rural areas are less likely to transport a trauma patient to a hospital in a neighbouring town that is some distance away, no matter what their condition, as they may not be confident in managing the patient or they do not want to ‘leave their town’ uncovered.

Study limitations

This study is subject to a number of potential limitations. Firstly, data used in this study was from a data repository that had been populated following an analysis of paper ambulance service patient care records (PCR) identified for a previous study. While it is believed that all available trauma PCRs were included in the data repository, the possibility of missing data cannot be discounted.

Finally, as there was some missing data on the PCRs, e.g. incident number, patient gender and age, there was not a 100% linkage between the original ambulance trauma dataset and state trauma registry dataset, therefore not all outcomes were identifiable.

Despite these potential limitations, this study has provided a unique insight into the outcomes of trauma patients who suddenly deteriorate in the presence of paramedics in Victoria, Australia.

Conclusion

This study suggests that the incidence of trauma patients suddenly deteriorating in the presence of paramedics is very low and that increasing the total out-of-hospital time to get these patients to an appropriate level trauma service does not adversely affect their mortality outcome. These results add to the knowledge base of trauma outcomes from a prehospital perspective, especially in Australia, and it forms a baseline for further studies.