In Canada, paramedic practice is seen as a broad discipline, often lacking common terminology and scope across vast regions with low population densities (Bowles et al, 2017; Statistics Canada, 2021). A lack of cohesion across the country is partly a result of healthcare being regulated provincially; in Ontario, paramedicine remains unregulated as a profession.

As healthcare resources in rural communities are minimal, paramedics are often relied on as a key point of contact for patients in both emergent and non-emergent cases, which is increasing demand on paramedics across the province. Between 2010 and 2019, call volumes related to the number of ambulance transports to a hospital increased in the rural and northern regions of Ontario following population growth (Strum et al, 2022). In Hastings County in Ontario, ambulance wait times increased by 30% over 7 years, from 7 minutes 59 seconds in 2015 to 10 minutes 23 seconds in 2022 (Ministry of Health, 2023). Wait times to see a health professional, including during an emergency response, are increasing steadily in Ontario, reflecting the current practitioner shortage.

New paramedics are needed to expand the workforce to the level required to staff additional ambulances and address this healthcare human resource crisis.

Critically, there is a bottleneck in the pathway to paramedic certification in Canada. In Ontario, students seeking to become a paramedic are required to enrol in a primary care paramedic diploma programme at a college. Students are eligible to graduate only once they have demonstrated competency through supervised placement and have met associated learning outcomes under the supervision of preceptors in their region. Upon graduation, students become eligible to sit for the advanced emergency medical care assistant examination; passing this is required to work as a paramedic in Ontario.

Customarily, second-year (fourth semester) students meet their learning outcomes, which are directly tied to the National Occupational Competency Profile (NOCP) for paramedics, by participating in an in-ambulance (IA) placement (Paramedic Association of Canada (PAC), 2011). This is a nationwide entry to practice standard.

According to the NOCP, proficiency in any competency is determined by consistency, independence, timeliness, accuracy and appropriateness (PAC, 2011).

During placements, paramedic students respond to 911 calls that are often random and unpredictable and this, paired with variability in the number of calls occurring in rural areas, can make the achievement of some competencies challenging (Strum et al, 2022).

The theory-practice gap experienced by new paramedics can be partially attributed to the nature of traditional IA service models, where clinical placements may be considered chance encounters with no means of predicting caseload, type or skill set use (Smith, 2016). Health worker shortages mean there are too few paramedics available to serve as training preceptors in both urban and rural areas, further complicating the potential for students to complete paramedic placements and graduate in a timely manner.

The PAC (2011) acknowledges the health worker crisis and explains that educators have struggled with limited resources as well as access to supervised clinical preceptorships. A shortage of qualified paramedics in the workforce can increase demands on them, making supervising placements more difficult and limiting the paramedic training system as students strive to complete their required practicum.

There are no requirements for where placements must occur, as paramedicine is an unregulated profession. However, it is commonplace to complete placements within an ambulatory setting. Adding to the difficulty in finding placement opportunities is that paramedic services lack standardisation regarding preceptor training and recognition for the preceptor role. While some paramedic services have certified field training officers, others simply circulate an email looking for volunteers to supervise a student during their placement.

The role of the paramedic is shifting, as demands have broadened within the healthcare system. Paramedics in Canada are now often integrated into emergency response agencies as partners in public safety, which has increased expectations of paramedic training programmes (PAC, 2011). Despite these expectations, there is a gap between theory and practice, where paramedic students may feel they have not accumulated sufficient experience before employment (Kennedy et al, 2015). Programme standards have not evolved as quickly as the paramedic scope in the province, and do not include content related to emerging fields of paramedic practice such as palliative care, community paramedic programmes and pandemic response. Research has found that the breadth of possible on-scene treatment can lie beyond the grasp of current paramedic practice, as new graduates have experienced difficulty with the recognition, diagnosis and management of conditions (Kennedy et al, 2015).

The traditional method of IA placement remains the norm and has not been thoroughly challenged in Ontario colleges. Traditional IA placement varies from college to college, and there is no legal minimum number of hours required as the focus is on competency achievement. The average number of hours per placement across Ontario colleges is approximately 420 hours, a reflection of the hours available to fit placements within a typical semester (12 weeks).

There is a lack of research on non-traditional or out-of-ambulance (OOA) paramedic placement and focused training interventions for knowledge development (Devenish et al, 2019; Lord et al, 2019; Credland et al, 2020; Hill et al, 2023).

Offering placements in predictable environments may provide opportunities for different types of learning and skills development (O'Meara et al, 2014a), which can translate into work readiness through an increase in confidence (Devenish et al, 2019). Evaluation of OOA clinical practicums shows they can lead to a variety of learning (Devenish et al, 2019) and the development of interprofessional relationships, facilitating collaboration (Reeves et al, 2013).

Aims

This study aims to evaluate whether NOCP paramedic competencies can be achieved in an OOA placement model through the supervision of competency completion. If this evaluation is positive, this OOA placement model will have the potential to increase completion rates of Canadian college paramedic programmes and could also inspire the re-evaluation of the colleges' selfimposed duration requirements for IA placements, which is 12 weeks or 420 hours. If students can achieve competencies in targeted clinical placements, the value behind the many hours of traditional ambulance placement may be reconsidered (Reid et al, 2019).

Methods and research design

This study used student assessments for the NOCP, collected for those in the paramedic diploma programme at Loyalist College in Belleville, Ontario. This programme is 2 years in length, compromising four semesters, and qualifies graduates as primary care paramedics in Canada. Participants in this study were in their second year, completing their final field placement in semester four. They were selected from a database of students who had previously expressed interest in the hybrid programme.

In accordance with Loyalist College academic operational policy 220, this study received Loyalist College research ethics board approval (reference number LC-REB2023-52VB).

Students were emailed an information letter about the study and asked to sign a consent form if they were interested in taking part. They were free to withdraw consent from the study at any time, without penalty, by providing written notice. Involvement in this research study consisted of participants giving consent to the secondary use of their data originally collected for academic requirements.

Paramedic students were assigned IA and community agency (OOA) placements for a duration of 12 weeks.

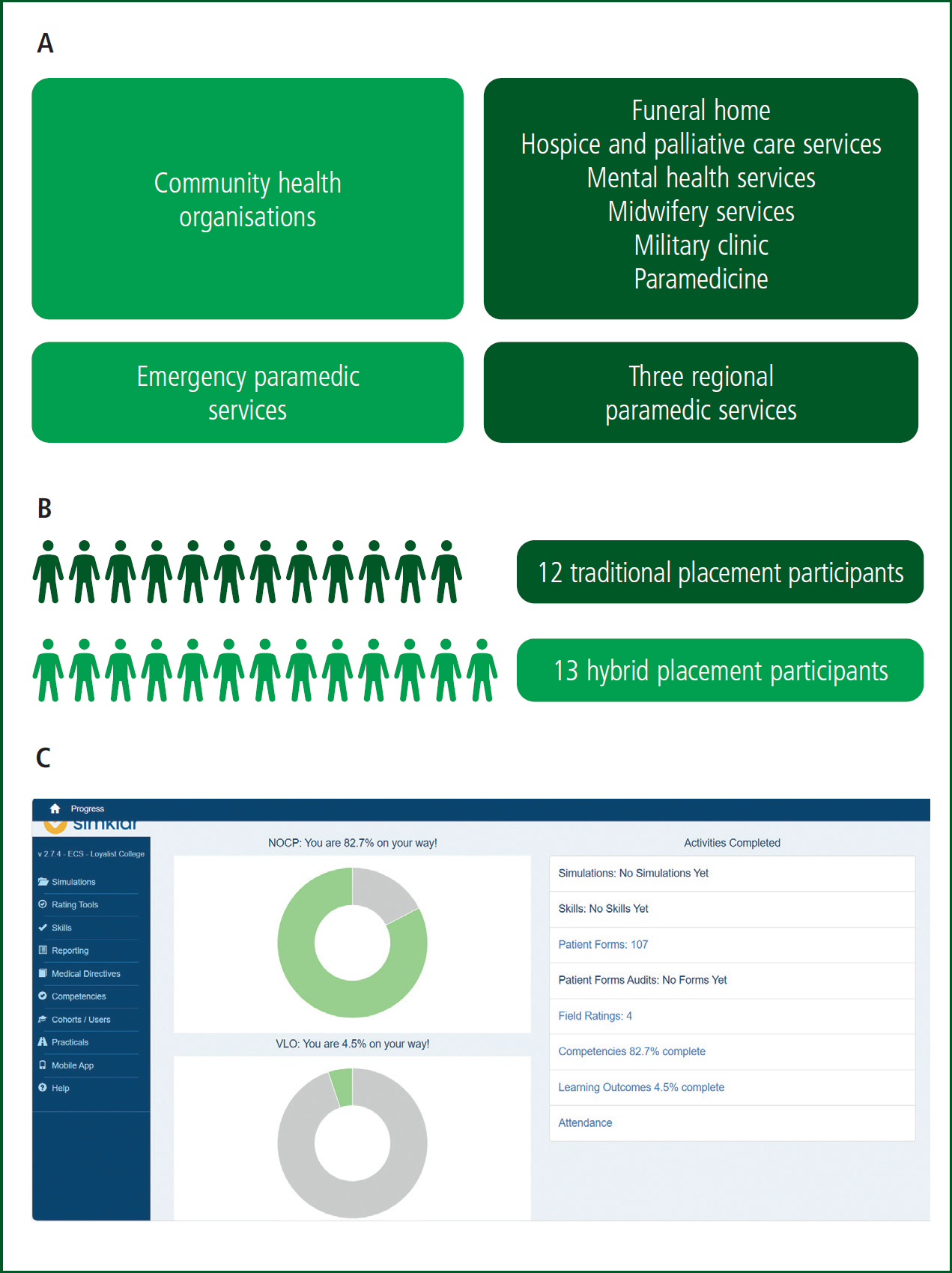

The traditional IA placement model was assigned to three emergency paramedic services (A, B and C) for the duration of their placement (Figure 1A).

Participating service agencies for the hybrid model included the previously mentioned ambulatory settings, as well as a funeral home, hospice and palliative care services, mental health services, midwifery services, a military clinic and community paramedicine (Figure 1A). The college staff leading this project selected community partners based on the possibility of exposure to clinical scenarios that could offer an educational experience typically of low frequency in the ambulance placement or an environment that promoted interdisciplinary collaboration but where similar skill sets were required. Examples include attending a childbirth with midwives and assessing vital signs and communication with a clinic or funeral home. All community partner organisations were selected for their alignment with frontline health care.

The occurrence of on-scene deaths for emergency paramedic calls is high in rural locations. Urban emergency medical services are associated with faster response times, less on-scene time, shorter transport times and higher patient survival rates than rural services (Alanazy et al, 2019). The funeral home provided a unique opportunity to nurture trainees in mental health practices such as supporting distressed loved ones and coping with the personal distress of addressing death, which can often be a reality of the discipline.

Community partners selected their preceptors; these were not all paramedics but were qualified in professional health disciplines that matched the skill set and scope of competencies required for college programme completion. The Loyalist College paramedic programme coordinator and placement coordinator provided support and training to the selected preceptors. Training for community partner preceptors included providing an information package, guiding principles, training on NOCP expectations and training on sign-off submission. Preceptors played a direct role in the supervision, guidance and oversight of participants during their placements.

The 13 students in the hybrid group attended their placements within surrounding regions and completed tasks within the normal expectations of involvement for their training requirements (Figure 1B). These participants spent 1 week at each of the six OOA community organisations, and the remaining 6 weeks in traditional IA placements, in no particular order.

Students participated in patient care in a variety of situations, and their competencies and achievements were tracked through SimKlar, the paramedic competency tracking software used by Ontario colleges, after each shift (Figure 1C).

Delegated medical acts (DMAs) were performed only in IA placement settings. Opportunity for students in both placement models to participate in DMAs varied, depending on the availability of a base hospital physician (BHP) to provide oversight for the IA placement at any given time.

Delegation occurs when a regulated health professional who is legally authorised to perform a controlled act temporarily grants their authority to perform that act to another individual under the Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991 (Government of Ontario, 2023). This law details 14 acts that a physician or their delegate can perform; it is within the paramedic scope of practice to perform nine of these procedures when the paramedic is certified under a BHP who is licensed to practise in Ontario (Ontario Paramedic Association, 2024). While both groups had opportunities to participate in DMAs, these were more frequent for those on traditional IA placements.

Twelve students who attended their placements under the traditional model voluntarily consented to competency tracking for this study (Figure 1B).

Data were anonymised and exported by a SimKlar technician to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and returned to the research team for analysis. Five blinded research assistants completed data analysis under the supervision of the research associate and principal investigator. Data analysis of competencies achieved, the organisation under which they were achieved and speed of competency achievement were analysed using Microsoft Excel. The level of proficiency in each competency was not tracked or analysed. Measures of frequency were examined to determine how many competencies were achieved and not achieved by participants, the number of times each competency was achieved, the number of days taken to achieve a competency and the number of competencies achieved at each organisation. Measures of central tendency and position were then examined to determine means and modes for the measures of frequency.

Results

Participant data were sorted to reveal if specific competencies (Table 1), including their sub-competencies, were achieved for each participant, under which organisation they were achieved and the speed of achievement.

Table 1. Paramedic competencies

| 1.1 Function as a professional | 5.1 Maintain patency of upper airway and trachea |

| 1.2 Participate in continuing education and professional development | 5.2 Prepare oxygen delivery devices |

| 1.3 Possess an understanding of the medico-legal aspects of the profession | 5.3 Deliver oxygen and administer manual ventilation |

| 1.4 Recognise and comply with relevant provincial and federal legislation | 5.4 Utilise ventilation equipment |

| 1.5 Function effectively in a team environment | 5.5 Implement measures to maintain haemodynamic stability |

| 1.6 Make decisions effectively | 5.6 Provide basic care for soft tissue injuries |

| 1.7 Manage scenes with actual or potential forensic implications | 5.7 Immobilise actual and suspected fractures |

| 2.1 Practise effective oral communication skills | 5.8 Administer medications |

| 2.2 Practise effective written communication skills | 6.1 Utilise differential diagnosis skills, decision-making skills and psychomotor skills in providing care to patients |

| 2.3 Practise effective non-verbal communication skills | 6.2 Provide care to meet the needs of unique patient groups |

| 2.4 Practise effective interpersonal relations | 6.3 Conduct ongoing assessments and provide care |

| 3.1 Maintain good physical and mental health | 7.1 Prepare ambulance for service |

| 3.2 Practise safe lifting and moving techniques | 7.2 Drive ambulance or emergency response vehicle |

| 3.3 Create and maintain a safe work environment | 7.3 Transfer patient to air ambulance |

| 4.1 Conduct triage in a multiple patient incident | 7.4 Transport patient in air ambulance |

| 4.2 Obtain patient history | 8.1 Integrate professional practice into community care |

| 4.3 Conduct a complete physical assessment, demonstrating appropriate use of inspection, palpation and percussion | 8.2 Contribute to public safety through collaboration with other emergency response agencies |

| 4.4 Assess vital signs | 8.2 Contribute to public safety through collaboration with other emergency response agencies |

| 4.5 Utilise diagnostic tests | 8.3 Participate in the management of a chemical, biological, radiological/nuclear, explosive (CBRNE) incident |

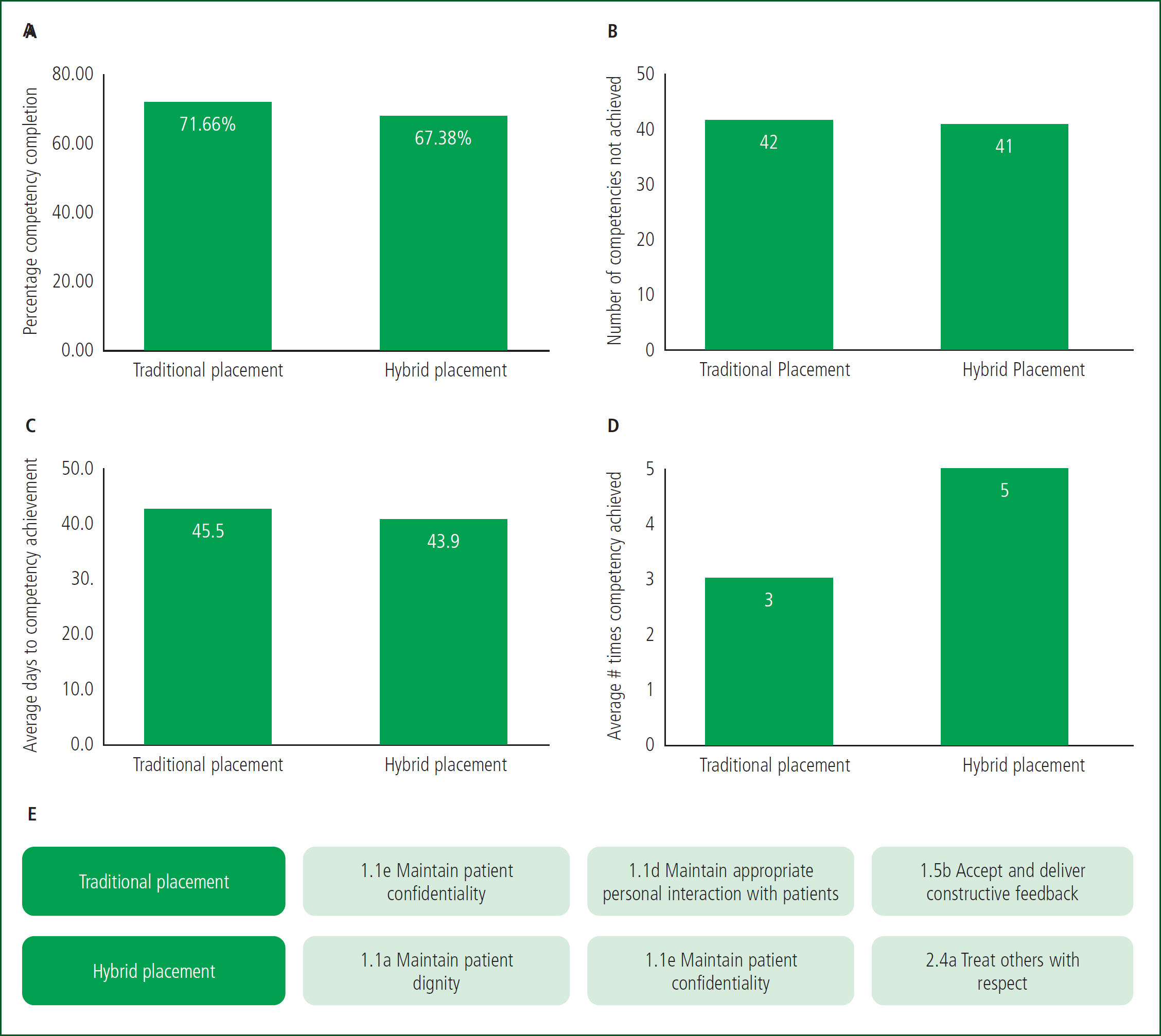

On average, participants in the traditional IA model achieved more competencies than the hybrid cohort, achieving on average 71.66% of specific sub-competencies compared to 67.38% for those on the hybrid scheme (Figure 2A). Values were calculated out of 187 specific sub-competencies required by the academic programme.

Traditional IA model participants had a greater number of competencies not achieved. Specifically, they did not achieve 42 of the required competencies and hybrid model participants did not achieve 41 (Figure 2B).

The average number of days taken to complete competencies during placement for the traditional and hybrid models were 45.5 days, and 43.9 days respectively (Figure 2C). The average number of times a specific competency was achieved in the hybrid placement model was five times compared to three times by participants in the traditional IA model (Figure 2D).

Of the top three competencies most achieved, both cohorts achieved competency ‘1.1e Maintain patient confidentiality’;. The two individual competencies achieved most by each cohort are shown in Figure 2E.

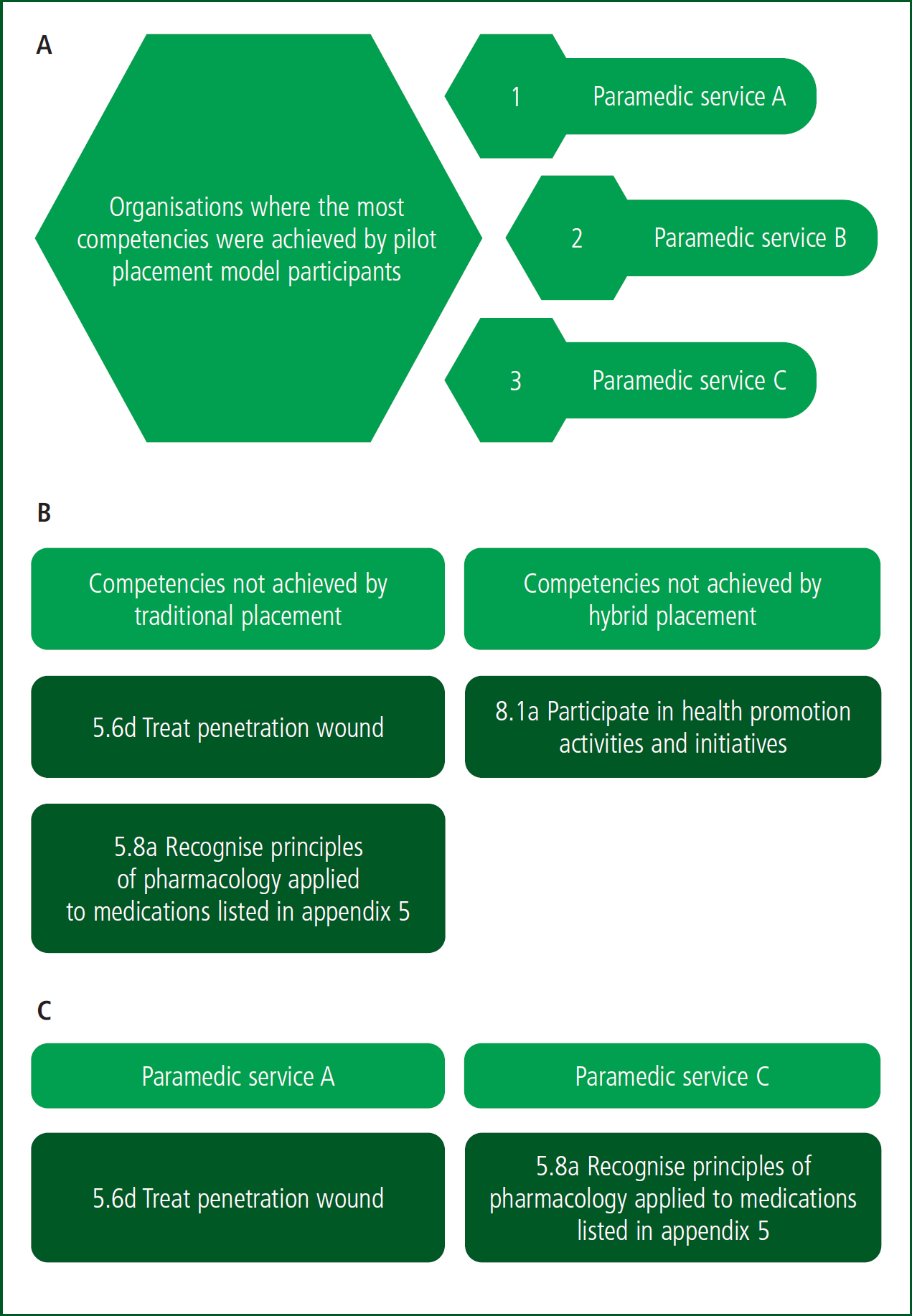

Analysis of the partner organisations for the hybrid cohort (Figure 1A) revealed that most of their competencies were achieved during their placement with traditional IA services (Figure 3A).

Within both placement cohorts, 40 competencies were not achieved, equating to 22.47% (Table 2). Comparison of each cohort revealed two competencies were not achieved by the traditional cohort but were achieved in the hybrid cohort: ‘5.6d Treat penetration wound’; and ‘5.8a Recognise the principles of pharmacology applied to medications listed in appendix 5’ (Figure 3B). In contrast, the hybrid model had one competency not attained that was achieved with the traditional model: ‘8.1a Participate in health promotion activities and initiatives’ (Figure 3B). Figure 3C shows the locations where the competencies were achieved only in the hybrid placement from Figure 3B.

Table 2. Sub-competencies not achieved by either cohort

| 1.1f Participate in quality assurance and enhancement programmes | 5.3c Administer oxygen using controlled concentration mask |

| 1.1h Participate in professional association | 5.5j Conduct manual defibrillation |

| 1.2a Develop personal plan for continuing professional development | 5.5p Provide routine care for patients with ostomy drainage system |

| 1.2b Self-evaluate and set goals for improvement as related to practice | 5.8e Administer medication via intravenous route |

| 1.2c Interpret evidence in medical literature and assess relevance to practice | 5.8g Administer medication via endotracheal route |

| 1.2d Make presentations | 5.8o Provide patient assistance according to provincial list of medications |

| 1.3b Recognise the rights of the patient and implications on the role of the provider | 6.2f Provide care to the bariatric patient |

| 2.2b Prepare professional correspondence | 7.1b Recognise conditions requiring the removal of vehicle from service |

| 3.1a Maintain balance in personal lifestyle | 7.3a Create safe landing zone for rotary-wing aircraft |

| 3.1b Develop and maintain an appropriate support system | 7.3b Safely approach stationary rotary-wing aircraft |

| 3.1c Manage stress | 7.3c Safely approach stationary fixed-wing aircraft |

| 3.1d Practice effective strategies to improve physical and mental health related to career | 8.1b Participate in injury prevention and public safety activities and initiatives |

| 3.3e Conduct procedures and operations consistent with Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS) training and hazardous materials management requirements | 8.1d Utilise community support agencies as appropriate |

| 4.1b Assume different roles in a multiple patient incident | 8.2b Work within an incident management system |

| 4.1c Manage a multiple patient incident | 8.3a Recognise indicators of agent exposure |

| 4.3p Conduct bariatrics assessment and interpret findings | 8.3b Assess knowledge of personal protective equipment |

| 4.5b Conduct end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring and interpret findings | 8.3c Perform CBRNE scene size up |

| 5.1c Perform suctioning beyond oropharynx | 8.3d Conduct triage at CBRNE incident |

| 5.1g Utilise airway devices not requiring visualisation of vocal chords and introduced endotracheally | 8.3e Conduct decontamination procedures |

| 5.2a Prepare oxygen delivery devices | 8.3f Provide care to patients involved in CBRNE incident |

CBRNE: chemical, biological, radiological/nuclear, explosive Source: Paramedic Association of Canada (2011)

Discussion

Rural placements have been shown to intrinsically possess opportunities for interprofessional learning and practice, because of their range of formal and informal contexts, as well as variety in organisational structure (Spencer et al, 2015).

While interprofessional learning was not measured for this study, interprofessional collaboration was prominent in OOA models, with paramedic students working alongside and under the preceptorship of health professionals outside the paramedic role. The concept of community paramedicine has been identified as progressively advantageous for rural communities. An increased scope of practice through community paramedicine positions paramedics to better serve their communities (Spencer-Goodsir et al, 2022). Studies evaluating alternative placements have highlighted the benefits of exposure to different aspects of the healthcare continuum (Stratton et al, 2015; Smith, 2016; Devenish et al, 2019).

Spending a longer time in an ambulance does not directly correlate to greater competence (Reid et al, 2019). In some cases, ambulance placements have been a negative experience for students, with significant downtime and preceptor attitudes cited as factors leading to this (Boyle et al, 2008).

This study provides an evaluation of an alternative model of placement to meet the growing need for qualified paramedics in rural communities.

Analysis of the raw competency data revealed that the hybrid placement model performed comparably to the traditional IA model, with some advantages and disadvantages. One observed disadvantage is that participants in the traditional IA placement model completed 4.28% more competencies than the hybrid model. While a minimum of 80% completion for competencies is required, adequate preparedness for the role is presumed with higher competency achievement.

One possible contributor to this difference may have been that the traditional IA participants had more opportunities to participate in DMAs as these were performed variably only at ambulance placement sites.

Participants may also have neglected to record every single competency or, once the minimum completion rate was reached, failed to remain diligent in recording additional competencies. There was a negligible difference in total competencies not achieved in each cohort (42 for traditional placement; 41 for hybrid placement).

Advantageously, the hybrid placement model resulted in competencies being achieved in a shorter period—1.6 days sooner on average (3.6% faster). The range of environments offered in the hybrid model may have influenced the ability for students to achieve their competencies in a shorter time frame. The nature of the OOA placements allowed more time and opportunity for skill repetition, possibly increasing confidence with that skill, reflected by higher numbers of repeated competencies in the hybrid cohort. This gives an advantage to students participating in the hybrid model, narrowing the theory-practice gap often experienced by newly trained paramedics.

A possible area of research is to explore the timing of OOA placements on student outcomes, as a study from 2017 found that student competencies across many skill categories significantly increase later in their placement (Wongtongkam and Brewster, 2017).

Further analysis into the types of competencies achieved revealed patterns. Of the 40 specific sub-competencies not achieved by any of the participants, many reflected areas relating to personal professionalism such as maintaining balance in personal lifestyle (3.1a), specific clinical practices such as conducting manual defibrillation (5.5j) or specific emergency call approaches such as creating a safe landing zone for rotary-wing aircraft (7.3a). While the rationale for non-achievement was not investigated in this study, these outcomes could indicate issues such as lack of time or ability to prioritise personal professionalism while on duty, and the variability and unpredictability of emergency calls in a rural region.

The hybrid placement uniquely provided opportunities for practice with certain competencies such as ‘1.1a Maintenance of dignity’ with patients, and ‘2.4a Treatment of others with respect’. The traditional model participants' inability to achieve competencies relating to ‘5.6d Treat penetration wound’ and ‘5.8a Recognise principles of pharmacology applied to medications listed in appendix 5’ may further speak to the unpredictable nature of ambulance calls, and the possible benefits of targeting specific competencies.

Similarly, the hybrid model participants' inability to achieve ‘8.1a Participating in health promotion activities and initiatives’ could reflect the nature of the community health organisations they were placed with. Health promotion activities and initiatives may need to be planned endeavours for community health organisations, whereas paramedics working in ambulances may have more opportunity to interact with members of the public in this realm. For example, paramedic services A, B, and C may also have participated in knowledge dissemination to the public while on calls, as seen in other studies (Bowles et al, 2017; McCann et al, 2018).

The most common organisations under which competencies were achieved for hybrid model participants were paramedic services A, B and C. Additionally, the competencies that the hybrid participants achieved but the traditional participants did not were done while working alongside the three paramedic services. These points indicate that the ambulance placement model continues to be valuable for achieving competencies; however, more competencies may be achieved, and skills gained when this model is coupled with other locations in a hybrid approach.

Though the hybrid model demonstrated efficacy in this study, reproducibility may be affected by the unpredictable nature of paramedic calls and health crises that arise at hybrid placement locations. Hybrid model participants attended their placement locations in no particular order, and it would be prudent to investigate whether attending a paramedic service in the first 6 weeks has any effect on competency achievement. As this research relied upon students self-reporting repeat competency achievement, it is possible students in either cohort achieved competencies more often than reported. This metric could be a leading indicator for confidence with a particular competency and may be of interest to formally track within the SimKlar system. Future investigations could include the students' perception of competency in relation to the number of times one was achieved, as well as investigating the impact of the Dunning-Kruger effect on this type of self-reporting.

The nature of competency achievement relies upon trained preceptors to provide sign-off to students. In this study, community partners were trained on how to provide sign-off for these competencies by the Loyalist College paramedic programme coordinator. Students on both the traditional and hybrid models were expected to self-report; however, the preceptors reviewed the entire list of submitted competencies and were trained to decline any competencies they felt the student did not meet. Future studies could investigate methods of training non-traditional community partner preceptors to ensure academic rigour is upheld.

Preceptor attitudes have previously been found to have implications for student learning; as such, adequate training for preceptors is a critical component of this type of learning (Boyle et al, 2008; Edwards, 2011; Baranowski and Armour, 2020). On an international scale, there is lack of consensus relating to the assessment of competency achievement for paramedic training, including the length of assessment, what resources are given to preceptors for assessment and interrater variability (O'Meara et al, 2014b; Smith et al, 2023). Future studies could examine the financial implications of the hybrid placement model's use of non-paramedic preceptors on regional resources and the health care sector.

Conclusion

Practical placement is an essential part of the learning trajectory for paramedic students. Given the NOCP requirements, paramedic placements should encompass an interdisciplinary and comprehensive approach to competency achievement.

This evaluation suggests that paramedic competencies can be achieved in an environment outside the traditional ambulance service. This study represents an opportunity for paramedic training institutes to adopt a hybrid model of preceptorship for paramedic students. The outcome of this practice could be a higher volume of students able to complete placements, and unique skill development owing to guaranteed exposure to specific competencies related to each community placement. Students may also benefit from early career exposure to interdisciplinary teams, where communication and problem-solving are commonly practised.

On a larger scale, this model could offer a potential solution to the issue of paramedic shortages resulting from the bottleneck in the paramedic training pathway. Moreover, there are possible benefits to society at large, such as the addition of more qualified paramedics to the workforce and added value to community partners from having clinical professionals on site.

This hybrid model holds value in its ability to increase the speed, degree and variety of competency achievement for students, but is found to be most successful when accompanied by adequate placement time in an ambulance service model.

Future studies may aim to assess qualitative feedback from students and preceptors on their perceptions of the hybrid model and to explore the scheduled timing of OOA placement on competency achievement.

CPD Reflection Questions

- Which types of community partners could provide valuable or unique experiences for trainees?

- Which competencies are critical for on-the-job preparedness but are often missed during placement?

- How might this type of placement benefit a community or region at large?

Key Points

- A lack of placement opportunities for paramedic students and health professionals to supervise them in practice create a bottleneck in the training pathway

- Paramedic competencies can be achieved in out-of-ambulance placements that are combined with traditional in-ambulance placements

- Community placements can augment learning for paramedic students

- Out-of-ambulance placements allow students to take part in interprofessional learning opportunities