Perhaps one of the less well-acknowledged demographics seen in prehospital care is the obstetric patient. This demographic makes up 5% of the caseload managed by the London Ambulance Service, which means obstetrics is uncommon but certainly not rare (McLelland et al, 2016).

In addition, paramedic training often focuses on critical illness rather than the range of presentations seen during pregnancy.

In light of this minimal patient exposure, the current literature review aims to alleviate some of the mystery of lesser known issues that arise during early pregnancy (defined as ≤20 weeks' gestation) by discussing its assessment and management.

The objectives of this paper are to describe what are considered normal symptoms in pregnancy as well as looking deeper at some key pregnancy-associated conditions that may present within this time period. Ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, rhesus incompatibility and hyperemesis gravidarum shall be discussed as they will be most relevant to the prehospital clinician.

It must be noted that many conditions not related to pregnancy, such as infection, gall bladder disease, cervical polyps or appendicitis, to name a few, still must be considered but are not covered in this article (BMJ Publishing Group, 2021).

It is important to understand the natural physiological changes that occur in women during pregnancy and how they are related to the different trimesters. In the current article, a simplified version of the trimesters are used for ease of remembering: the first trimester (1–12 weeks); the second trimester (13–27 weeks); and the third trimester (28-40 weeks) (NHS, 2021a).

A fundamental element of many pregnancy-related changes is the adjustment of hormone levels. The three key hormones are oestrogen, progesterone and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which continue to increase throughout most of the pregnancy. hCG is the hormone measured in pregnancy tests as it occurs naturally only during the development of the foetal membrane (Jenkins et al, 2010). Changes in the vital signs occur within the first 5–8 weeks of pregnancy and are described in the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) UK Ambulance Services Clinical Practice Guideline (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2019). A brief overview of changes in early pregnancy is given in Table 1.

| Respiration rate | Gradually ↑, typically seen in second trimester |

| Heart Rate | ↑ 10–15 beats per minute within first trimester |

| Blood Pressure | Systolic and diastolic ↓ 10–15 mmHg within first trimester |

| Cardiac output | ↑ 20–30% in first trimester |

| Blood volume | ↑ 45% Change in blood volume is mostly a rise in blood plasma compared to red blood cells; ratio=1:0.5 |

These physiological changes will cause women to develop several common symptoms which in themselves are of no clinical concern. These may include a transient postural light-headiness upon standing, muscle cramps, peripheral oedema or the classic occurrence of urinary frequency (Beebe and Myers, 2011; Murtagh and Rosenblatt, 2015). Even the bizarre occurrence of pica (the craving for non-nutritional substances including soil, ice and chalk) can occur and may be a sign of micronutrient deficiency (e.g. anaemia from the relative dilution of red blood cells) (Fawcett et al, 2016). All of these symptoms are unlikely to cause difficulty for the average prehospital practitioners.

Abdominal pain in early pregnancy, on the other hand, whether the patient realises she is pregnant or not, is less easy to assess and is more likely to be seen prehospitally.

Abdominal pain

Common benign causes of abdominal pain include bloating, constipation and round ligament syndrome (Hopcroft and Forte, 2003).

Rising progesterone levels cause a reciprocal decrease in gastric motility. This can lead to the intermittent bloating pain and constipation seen in 25–40% of pregnancies (Keller et al, 2008; Trottier et al, 2011). Constipation, although common in pregnancy, seldom presents to general practice and is therefore is less likely to present to emergency ambulance services (EAS) (Hopcroft and Forte, 2003). For this reason, constipation should be very low on the list of differential diagnoses the prehospital practitioner should consider. Treatment includes changes to diet with the addition of laxatives if required (Trottier et al, 2012).

Finally, round ligament syndrome is typically seen from the second trimester but can present earlier. It is caused by the natural stretching of the uterus and various ligaments within the adnexa, predominantly the round ligaments; it is secondary to rising progesterone levels and the expanding size of the uterus (Chaudhry and Chaudhry, 2020). This may cause an intermittent, sharp pain which is usually lateral to the left or right iliac fossa but sometimes both and can be moderate in severity (Hull University Teaching Hospital, 2020).

However, as this closely resembles the pain seen in ectopic pregnancy, it should only be a diagnosis of exclusion. Simple analgesia and heat packs are usually sufficient to manage symptoms (Chaudhry and Chaudhry, 2020).

On review, practitioners should assess whether these seemingly benign aetiologies are constant, severe in nature or associated with per vaginal bleeding (PVB). If any of these three are present, further assessment is advised.

Ectopic pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) is a dangerous condition which, more than any other condition discussed here, must not be missed.

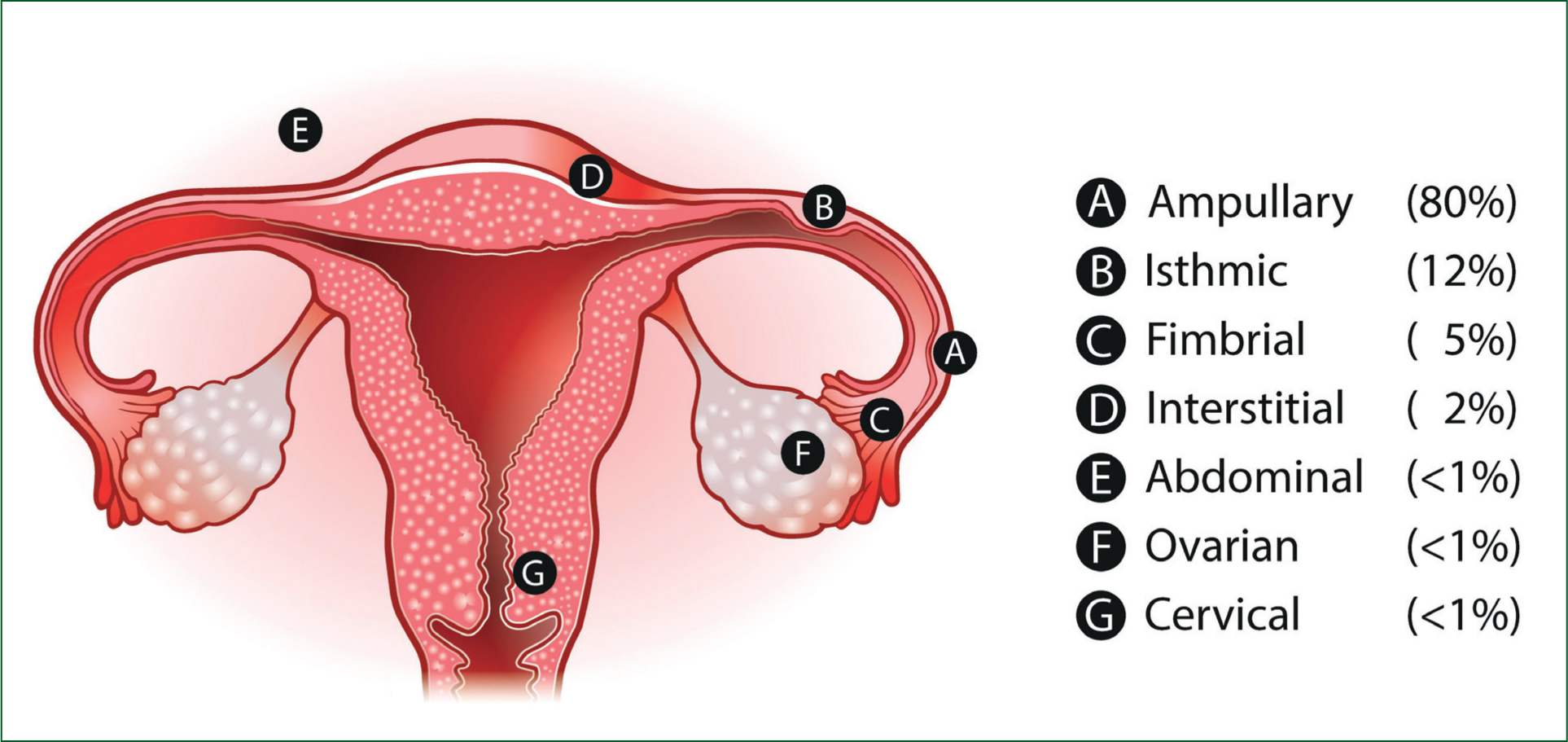

An EP is defined as any pregnancy implanted outside the endometrial cavity and has an incidence in the UK of approximately 11 per 1000 pregnancies (Elson et al, 2016). The overall mortality of EP in the UK is fortunately relatively low (estimated 0.2 per 1000 EPs); the clinical challenges of EP lie within the broad range of presentations seen (Trottier et al, 2012). Because of this, many deaths following EP occur because of missed diagnoses rather than a failure of treatment (Trottier et al, 2012). In terms of the various EP sites, the Ectopic Pregnancy Trust (EPT, 2021) states that tubal pregnancy (i.e. within the fallopian tube, including ampullary, isthmic and fibrial pregnancies) makes up 95–97% of cases, followed by other possible placements (Figure 1).

Because the vast majority of EPs occur in the fallopian tube, clinical signs will commonly present at 6–8 weeks (Barnhart, 2021). Note that a patient's knowledge of gestational age may be marginally incorrect before the first ultrasound scan. The classic triad of symptoms (with their associated sensitivity) consists of: abdominal pain (80-90%); missed menses (75–90%); and PVB, often mild rather than heavy (50–80%) (Dart et al, 1999). However, as one in four of women will lack the full triad, absence is not sensitive enough to rule out EP (Dushenski et al, 2012). Other symptoms and risk factors are shown in Table 2.

| Symptom | Risk factors (OR) |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Sources: Karaer et al (2006); Johnson et al (2019); Barnhart (2021)

As seen in Table 2, certain contraceptive methods are risk factors for EP but the risk is only present if pregnancy occurs despite their use (<1% chance) (NHS, 2021b). Unfortunately the risk factors, similar to the symptoms, cannot be used to rule out an EP as 33% of cases will have no associated risk factors (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2021a).

If an EP is undetected, rupture may occur, resulting in potentially fatal intra-abdominal haemorrhage. It is a true medical emergency.

Diagnosis of a ruptured EP can be difficult as signs of shock, shoulder tip pain and syncope are often a late finding (Crochet et al, 2013). Some patients may present with a reflex bradycardia because of peritoneal irritation, which disguises the classic signs of shock (AACE, 2019).

A small prospective study (n=141) by Huchon et al (2012) looked at a clinical decision questionnaire for ruptured EP which had of four criteria:

A score of ≥1 criteria demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 44% at detecting rupture, making it potentially useful to rule out ruptured EP but poor to definitively diagnose.

If the patient has had an ultrasound scan confirming an intrauterine pregnancy, the likelihood of EP is drastically reduced; however, there have been cases of ultrasound scans being misinterpreted so practitioners should always use their clinical judgement (Dushenski et al, 2012).

It is clear that clinicians must have a very low threshold for considering EP until it is ruled out via ultrasound scan (Elson et al, 2016).

Per vaginal bleeding

PVB is seen in up to 10–15% of early pregnancies, many of which will be carried to full term (Harville et al, 2003).

A common presentation is light spotting which, if not associated with other symptoms, is usually benign and commonly caused by hormonal changes (Beebe and Myers, 2011). A prospective study (n=4510) by Hasan et al (2009) investigated the long-term consequences (>4 days) of varying degrees of PVB. This found that bleeding, described as less than the woman's normal menstruation, had no long-term increased risk of miscarriage than a pregnancy without PVB. However, this study excluded pregnancy loss that occurred within 4 days, so it cannot be used to rule out miscarriage in the short term.

Finally, slight bleeding seen at around 18–24 weeks may indicate a possible cervical weakness and warrants a pelvic examination plus foetal assessment (Murtagh and Rosenblatt, 2015).

Though PVB is usually benign, there are several factors to consider if this is a first-time bleed or if the bleeding is different (i.e. associated with pain, increased quantity or new symptoms).

Predominantly, what must be considered are rhesus incompatibility, miscarriage and EP.

Rhesus incompatibility

Rhesus incompatibility is the phenomenon where a rhesus negative (Rh-ve) blood type woman who is carrying a rhesus positive (Rh+ve) blood type foetus sustains a maternal-foetal cross-contamination of blood through a potential sensitising event.

Because the maternal immune system is unfamiliar with Rh+ve proteins present on the foetal red blood cells, it can perceive them as a foreign threat and may develop antibodies, depending on the level of sensitisation that occurs.

These antibodies, if formed, will encourage an immune response from the woman against the Rh+ve foetal red blood cells whenever cross contamination occurs in the future.

If sensitisation occurs and remains untreated, foetal anaemia, hydrops fetalis and foetal death may occur (Fung-Kee-Fung and Moretti, 2021). The treatment for rhesus incompatibility is anti-D immunoglobulin and, if given within 72-hours of the potential sensitising event, this has a high success rate of treatment and has reduced the occurrence of rhesus incompatibility from 16% to 0.17–0.28%. If the 72-hour window is missed, administration of anti-D immunoglobulin is still recommended up to 10 days later but it is less efficacious (Qureshi et al, 2014).

Examples of potential sensitising event relevant to prehospital clinicians includes (Qureshi et al, 2014; Timmins and Evans, 2016):

Two scenarios where anti-D immunoglobulin does not need to be considered are when the mother is Rh+ve or both biological parents are Rh-ve (making the foetus Rh-ve) (BMJ Publishing Group, 2020).

The final topic of PVB, and often most forefront within the mother's mind, is miscarriage.

Miscarriage

Miscarriage is not an uncommon occurrence worldwide. Up to 30% of known pregnancies will miscarry within the first trimester and <3% will occur within the second trimester (Muslim and Doraiswamy, 2021). Usually, miscarriage is caused by an abnormality of foetal development rather than any problems with the parents or the environment, which may be of some comfort to the parents (Dushenski et al, 2012). Dushenski et al (2012) state that there are six forms of miscarriage (Table 3).

| Threatened | Bleeding with closed cervix but no evidence of foetal demise on ultrasound scan; 50% chance of complete miscarriage |

| Inevitable | Open cervix but products of conception not yet expelled. Almost all progress to complete miscarriage |

| Incomplete | Products of conception partially expelled. All progress to complete miscarriage |

| Complete | All products of pregnancy are expelled |

| Missed | Ultrasound scan shows foetal demise but products of conception remain in uterus. Can be asymptomatic. All will progress to complete miscarriage |

| Septic | Rare. Often results from pelvic instrumentation (i.e. non-sterile conditions) |

Source: Dushenski et al (2012)

In threatened miscarriage, 50% of cases progress to full term and, if a foetal heart rate is detected via ultrasound scan (possible >7 weeks), this increases to 95% cases progressing to full term (Dushenski et al, 2012). The common clinical signs of miscarriage and risk factors are listed in Table 4 (Muslim and Doraiswamy, 2021).

| Clinical signs | Common risk ractors |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Source: Muslim and Doraiswamy (2021)

A retrospective study (n=426) by Al Mulhim et al, (2012) found that trauma associated with the second trimester, PVB, direct pelvic/abdominal trauma and major trauma were more strongly associated with traumatic miscarriage. Another study (n=341) by Sapra et al (2018) found that PVB within the first trimester had hazard ratio of 8.7 for pregnancy loss whereas bleeding within the second trimester showed no correlation.

Because miscarriage is so common, risk factors hold little value in making a diagnosis. As with EP, an ultrasound scan is the gold standard for confirming the viability of the pregnancy. Unfortunately, in all cases of miscarriage, there is no definitive treatment to save the foetus and management includes emotional support and analgesia if required prehospitally (Muslim and Doraiswamy, 2021).

Patients who are unstable because of life-threatening PVB or septic abortion are a medical emergency and should be managed via local protocol, typically via emergency transport.

Early pregnancy units

Clinicians will know that a ruptured EP or miscarriage with heavy or constant PVB require care via accident and emergency (A&E). Patients in early pregnancy who are stable and present with minor symptoms of pain and/or PVB may be more appropriately managed via an early pregnancy unit (EPU).

An EPU is a secondary care service that has access to anti-D immunoglobulin and, importantly, transvaginal ultrasound scanning equipment. Transvaginal ultrasound scan, compared with abdominal ultrasound scan which A&E departments more frequently use, has a higher accuracy in detecting the location and viability of a pregnancy, especially when gestational age is <6 weeks (Edey et al, 2007; Dushenski et al, 2012).

All EPUs are equipped to manage stable patients with rhesus incompatibility, EP and miscarriage as well as several other pathologies, and provide antenatal services.

Depending on the EPU, some will require referral via a GP while others accept walk-in appointments. All EPUs require the patient to be confirmed pregnant via hCG testing and to be under 15 weeks gestation (±1 week) (Edey et al. 2007). Clinicians should check with their local EPU/EAS to confirm their referral criteria/availability.

Nausea, vomiting and hyperemesis gravidarum

Nausea and vomiting (N&V) are very common in pregnancy and seen in approximately 75% of cases (Beebe and Myers, 2011). In the case of the benign ‘morning sickness’, women will tend to feel worse in the morning but should improve throughout the day.

Symptoms will typically start around 4–7 weeks, peak at around the 9–16 weeks and resolve by week 20 in 90% of cases (Shehmar et al, 2016).

Vomiting that begins after the 11th week or is associated with fever, abdominal pain or diarrhoea is seldom benign in nature and disease must be considered (Pontius and Vieth, 2019).

Interestingly, mild cases of N&V are associated with lower rates of pregnancy loss so may be good tidings for the pregnancy (Pontius and Vieth, 2019).

In cases of mild N&V where treatment is required, one out of five women noticed symptom improvement with ginger in a review via a meta-analysis by Thomson et al (2014), which included six randomised, controlled, placebo trials. If pharmacological intervention is required but the patient is suitable to be managed in the community, several options are available.

Shehmar et al (2016) advocates for a histamine H1-antagonist (e.g. promethazine) or a phenothiazine (e.g. prochlorperazine) as first-line pharmacological treatment (which can be organised via a GP).

However, in up to one in 200 pregnancies, a severe form of N&V termed hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) will develop. HG has several aetiologies that range from a more extreme version of pregnancy-related N&V to diseases such as molar pregnancy or gestational trophoblastic disease (Quinlan, 2021). Regardless of the cause, HG will require management via A&E (not an EPU) and, for this reason, the diagnostic criteria for HG will be the deciding factor for the prehospital practitioner (NICE, 2021b). The diagnostic criteria for HG are:

If the patient meets any of these criteria, admission is required for IV fluid therapy and antiemetics (Pontius and Vieth 2019). If admission is required, ondansetron may be administered, although JRCALC (AACE, 2019) lists pregnancy as a caution because of concerns of cleft-palate deformity. Shehmar et al (2016: 10) state that there is good evidence that ondansetron is ‘safe and effective’ citing a retrospective study (n=608 385), which demonstrated no increased incidence of cleft palate (Pasternak et al, 2013).

Conclusion

The present article has discussed some of the considerations when managing patients in early pregnancy. One thought for the future is that EAS should consider the introduction of hCG urine testing. Newbatt (2012: 40) states ‘all healthcare professionals involved in the care of women… should have access to pregnancy tests’. With EAS championing for managing patients safely outside of hospital, it is becoming ever-more important that prehospital clinicians have the capabilities and training to assess women who may be pregnant.