The blended approach to conflict resolution training was delivered during early 20102011, along with the required practical training inclusion. The programme was specifically designed to run on an internet-based platform, using bespoke prehospital interactive videos and scenarios to enhance the theoretical concepts of conflict resolution, while allowing students to learn and progress at their own pace. The programme took more than 6 months to design and move from concept to prototype, from testing to refining before the finished product was produced. As Krause stated in 2005:

‘Blended learning is realized in teaching and learning environments where there is an effective integration of different modes of delivery, models of teaching and styles of learning as a result of adopting a strategic and systematic approach to the use of technology combined with the best features of face-to-face interaction’

Course design for community responders

Community responders are usually members of the public that volunteer to attend 999 calls on behalf of the ambulance service and are primarily called to attend ‘Category A’ emergency calls. These are 999 calls that the ambulance service deem to be ‘serious and/or life-threatening’. Therefore, by their very nature, they may require medical assistance as quickly as possible, usually within 8 minutes of the 999 call being made. Community first responders undergo specific training to enable them to deliver life-saving care, including defibrillation.

National response time standards for emergency and urgent ambulance services have been set for the English ambulance services since 1974. The NHS Executive Review of Ambulance Performance Standards introduced revised standards following publication in July 1996, and these standards have most recently been updated in the NHS Operating Framework 2011–12 (Department of Health (DH), 2010).

Category A is the type of call most commonly suitable for first responders—presenting conditions that may be immediately life-threatening and need to receive an emergency response within 8 minutes, irrespective of location, in 75% of cases. Category A calls involve patients suffering from some of the following symptoms:

This list is not exclusive, but very much demonstrates the type of calls that community responders are volunteering to attend, providing valuable support on behalf of the ambulance service. Initiatives to set up community responder schemes and promote public access defibrillation have been supported by the British Heart Foundation for many years. Public access defibrillation is specifically relevant in rural areas such as those encountered across the southwest of England where an ambulance cannot always reach the scene straight away. The NHS ambulance services have to consider a number of safety considerations when using volunteers to respond on their behalf; and within the South Western Ambulance Service Foundation NHS Trust (SWAFST), the safety of those responding on our behalf has to be considered as the number one priority.

SWAFST ensures that their responder staff are never mobilized to dangerous calls, and has specific protocols in place to protect responder and lone worker staff using specific lone worker policies.

During 2009, the Directors of SWASFT felt that all staff with direct patient contact, including the volunteer community responders, should undergo a conflict resolution programme, as it can be seen as a valuable ‘life skill’. This stance is congruent with the recommendations of the counter fraud and security management services (NHS CFSMS, 2007), and supported by local health and safety executive advisors. During the design of e-learning tool, we worked closely with the health and safety executive and the NHS counter fraud and security management services (NHS CFSMS).

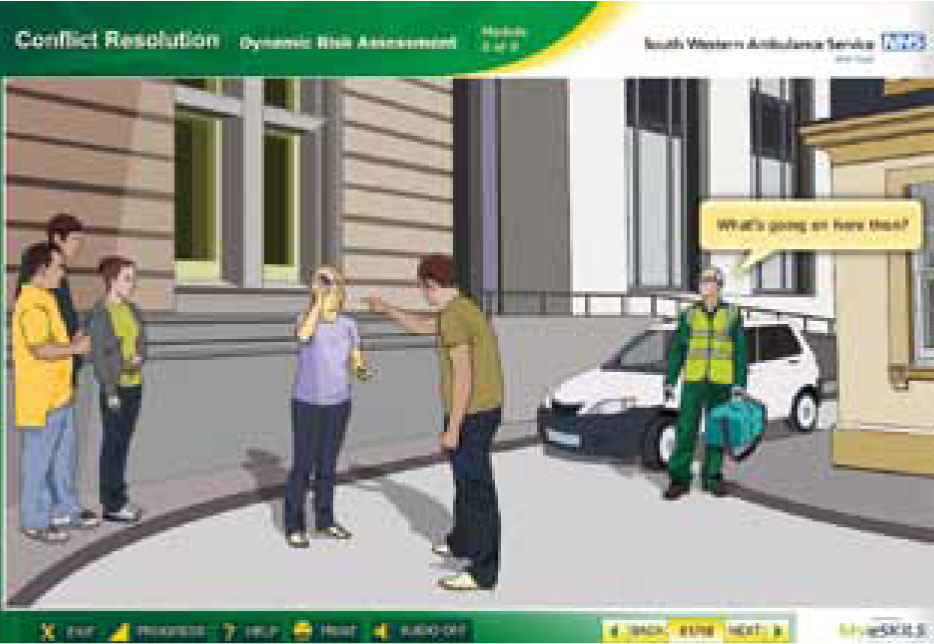

The course was specifically designed to equip the community responders with the skills to recognize when people may be frustrated, angry, aggressive or even violent, and assess if it is safe to resolve the situation themselves or move to a place of safety until help arrives. The course has been specifically designed for use by community responders and it has an ambulance ethos that enhances the feeling of belonging to a 999 emergency service. This was a deliberate move by the team designing the product as they were concerned that many of the conflict resolution courses on the market were not ambulance service specific, and did not cover the prehospital arena.

The course design team felt that prehospital conflict resolution was a different area of health care due to the unique environmental and logistical factors to which those working in the out-of-hospital environment are often exposed. Prehospital care workers and volunteers are often exposed to situations that are unique in healthcare; such as, the presence of domestic animals and the need to provide care outside. In addition, they are often exposed to the elements, or in low light conditions. It was for these reasons that the Trust chose to invest in a bespoke blended learning programme for community responders (Figure 1).

Blended learning

Oliver and Trigwell (2005) voiced some objections to the use of the term ‘blended learning’. They point out that the term has become a bandwagon for almost any form of teaching containing ‘two or more different kinds of things that can then be mixed.’ There is no consensus over what the learning aspects are that should be mixed—examples include different media, varying pedagogical approaches, or the mix of theoretical and practical work. Their main objection is that the distinctions being drawn do not exist, or are not productive. For example, the blending of e-learning with the traditional learning implies that there can be an unblended form of e-learning in which no traditional learning occurs. They also object to the use of the term ‘learning’, when almost all of the focus is on how teaching is delivered and the implication is that receiving teaching is equivalent to learning. This seems a valid argument; therefore, the SWASFT education team have put metrics in place to try and gauge the amount of learning that has taken place and its applicability to the real world. These metrics include the ability to not only review each summative question that the learner has been asked to undertake within every module, but also to ensure that learners are not penalized for poorly worded questions. The design team built in metrics to provide feedback on four key areas:

Graham (2005) suggests that a blended learning approach can combine face-to-face instruction with computer-mediated instruction since it aims to encourage learners and teachers to work together to improve the quality of learning and teaching. The ultimate aim of blended learning is the provision of realistic practical opportunities for learners and teachers to make learning independent, useful, sustainable and iterative. Heinze and Procter (2004) stated that:

‘Blended learning is learning that is facilitated by the effective combination of different modes of delivery, models of teaching and styles of learning, and is based on transparent communication amongst all parties involved with a course’.

This transparent communication was a vital component of our conflict resolution course design, and the team made a deliberate effort to use language that avoided jargon and that was understandable, and uncomplicated. The project was designed with the end user in mind, since the authors expect that, for many learners, nothing can replace the ability to tap into the expertise of a live instructor. We needed to ask what drives an effective learning event or product; and for educational theorists such as John Keller (1983; 1984; 1987), it comes down to the four elements described by his ARCS model of motivation: attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction.

ARCS model of motivation

Attention: the ability to hold the learners attention

The first aspect of the ARCS model is gaining and keeping the learner's attention. For example, an experienced classroom instructor may begin their class by telling a joke, or by polling the learners with a thought-provoking question. This process engages learners and prepares them for learning, online learning must do same. In our case, the attention grabbing elements are undertaken by presenting videos or real-life incidences which assist the learner with motivation.

Relevance: the ability to keep the learner focused

Learners stay focused when they believe the training is relevant to their specific situation, and to show relevance an instructor may use examples or analogies familiar to their audience. They may also show how learners can use course information to solve real problems. By designing a bespoke ambulance product, the community responders are encouraged to feel part of the organization.

Confidence: the ability to make the learner confident about what they learned

Learners must have confidence in their skills and abilities in order to remain motivated. To instil confidence in learners, an expert instructor will make classroom expectations clear, then give learners ample time to practice their new skills. As they experience success, learners gain confidence. This concept was used when designing the product, ensuring that theories of conflict resolution were tested and reinforced throughout.

Satisfaction: the ability leave the learner satisfied the learning was worthwhile

Learners must be satisfied with the results of their learning experiences in order to remain motivated. When designing the product, the team used educational theories such as Gagne's nine events of instruction (1985) to ensure that the product was educationally robust (Table 1).

Other factors of course design

In addition, the product was designed to be sharable content object reference model (SCORM) compliant, to ensure that the e-learning product adhered to a set of rules that specifies the order in which a learner may experience content objects. In simple terms, they constrain a learner to a fixed set of pathways through the training material while permitting the learner to ‘bookmark’ their progress when taking breaks. It ensures the acceptability of test scores achieved by the learner.

This was felt to be vital since it allowed community responders to leave the course at any stage—for example, in the event of a call, without having to begin the course at the beginning.

English language

The course has been designed to meet level 2 English, low to intermediate level of English language and is the equivalent of International English Language Testing System (IELTS) level 4. This was a deliberate attempt by the Head of Education for SWASFT to maintain the principles of plain English. The plain English concept, promoted by the plain English campaign (2011), was essential to programme design.

The language used in ambulance education had been a major concern of the design team. They felt that health care is wrapped up in specialist terminology that may be unfamiliar to new staff or those who are not immersed in the ‘specialist language’ on a daily basis; for example, our community responder staff.

The plain English campaign has been in place since 1979 and has a commitment to campaign against jargon, believing that everybody should have access to clear and concise information. By basing the product on language that was easy to understand, it was hoped that the product would have greater usability, and provide a positive experience for the learner.

Use of an internet approach

The internet-based approach means that the responders can access the course at any time or place where there is internet access, ensuring all staff are trained quickly and cost effectively. With volunteer first responder staff in SWASFT scattered across four counties, getting them into a single location to train is always a challenge for our responder managers. This is combined with a desire to reduce the amount of face-to-face teaching for our volunteers that are already giving up their valuable time to assist the service.

The face-to-face element of the conflict resolution course can now be covered in an evening session rather than having to ask our volunteers to give up a whole day. The three-hour e-learning course is focused on keeping staff safe, supporting the community responders by enabling the learning skills to assess people and situations where conflict may be present. It includes film clips of scenarios where judgments have to be made, and an assessment is provided at the end of each module; the results are tracked and monitored allowing managers to remotely view progress and results.

Reporting

SWASFT has commissioned an ambulance specific compliance-based reporting system using ‘My eSKiLs’, a learning management system that combines a very high standard of compliance reporting. The system has a comprehensive range of measurements to inform us of our learner satisfaction levels and organizational training success levels, providing stronger compliance and governance.

The automated tool will continue to assist us in measuring and evidencing our statutory and mandatory compliance training obligations across the Trust as we adopt the online learning approach in all areas. The system automatically assigns learners to courses, enrols, tracks and measures the learner's progress; and finally collects their course feedback, before awarding a certificate on successful course completion. The feedback information enables continual improvement of the course content, it's relevance to the learners and its ability to engage with learners throughout the course.

The benefits

Some of the typical benefits of the e-learning that we have encountered so far are shown below, and it:

In addition, we have reduced CO2 emissions by reducing travel to training centres. Based on early feedback (105 learners), the early adoption of the conflict resolution course has demonstrated compliance with:

Although this feedback is based on only two months of use, it suggests that the time spent on course design, and maintaining an end user and educationally compliant design to a bespoke ambulance product has been successful.

Cost effectiveness

The trust plans to roll-out internet-based training in other areas as it has proven to be a cost-effective, value for money, option that ensures that standards are maintained. The cost of a single days training for all front-line staff in SWASFT (1500 staff approximately) equates to approximately £250 000. This is mostly due to the costs associated with staff release to attend training, and to the cost of backfill on the ambulances. There are further costs such as classroom, tutor wages etc, associated with standardized training. This can also be reduced through the use of electronic learning.

The future

Attempts have been made to procure and design further bespoke ambulance specific products that meet the needs of all ambulance trusts in the UK. Within SWASFT, we are planning products that will support clinical developments for other groups of staff. Our educational design team are also seeking to adjust the conflict resolution course to ensure that it meets the needs of front-line staff. The move towards electronic patient report forms will enable SWAFST to have e-learning platforms on ambulances; therefore, the concept of e-learning for front-line staff would also be a realistic consideration.

Conclusion

As a solution to a problem of how to deliver conflict resolution to more than 900 volunteers spread across the counties of Dorset, Somerset, Devon, Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, the design of a bespoke product to teach ambulance first responders the theoretical concepts of conflict resolution using an e-learning product has been a huge success and has provided a value for money solution.

The combination of e-learning and face-to-face practical learning provides a blended learning solution to conflict resolution which is unique in UK ambulance trusts. The team in SWASFT are evaluating the effectiveness of the learning with a view to developing more ambulance specific products in coming years.