Paramedic-driven research is fast becoming a core component of professional development, guided by the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) (Griffiths and Mooney, 2011). The HCPC suggests that paramedic registrants should not only recognise the value of research but also engage in evidence-based practice, be aware of research methodologies and evaluate research to inform clinical practice (HCPC, 2007). Paramedics have increasingly become more involved in prehospital research, which has led to changes in clinical and operational guidelines (Bigham et al, 2010).

Despite this progress, Griffiths and Mooney (2011) suggest that paramedic-led research in the UK is limited. However, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (Munro, 2016) said that the NHS cannot fail to notice the evolution of ambulance service-led research. Ambulance trusts, often in partnership with universities, have developed landmark studies, including the PARAMEDIC2 (Perkins et al, 2018) trial, SAFER2 trial (Snooks et al, 2017), RIGHT2 (Bath et al, 2016) and AIRWAYS2 (Benger et al, 2018), not only recruiting large numbers of participants but also engaging thousands of paramedics.

To support paramedics in research, Health Education England and the National Institute for Health Research have introduced clinical academic programmes to modernise training, education and careers in clinical and healthcare research (HCPC, 2014). Clinical research academic programmes are extremely valuable and work by enabling robust clinical research to improve patient care and outcomes while facilitating a successful career for practitioners as both clinician and researcher (Kapoor et al, 2011).

A paramedic and novice researcher undertaking a master's degree in clinical research requires support, not only from an academic perspective but also from those with research expertise specific to paramedicine (Clancy, 2007). A key challenge to the evolution of research within paramedicine is the facilitation of paramedic-led research projects (Griffiths and Mooney, 2011). To encourage and support the novice researcher, Jones and Jones (2009) suggest a contextual learning experience by getting research students and academics with a background in paramedicine to collaborate to overcome barriers in the development of research metholodologies.

Therefore, when designing an explanatory, sequential, mixed-methods research study, the aim of engaging research paramedics and paramedic clinical academics with research expertise was to ensure the research design was appropriate to the complexities of prehospital research. In addition, this would reflect the fundamental elements required for successful research outcomes (Bigham et al, 2010).

Professionals and practitioners are stakeholders who, as individuals or groups, can engage to provide support and information regarding health research, giving a critical perspective and alternative insights on complex healthcare issues (Schiller et al, 2013).

The proposed research study requiring professional paramedic engagement aims to explore how senior clinical paramedic advisers (SCA) determine futility in pulseless electrical activity (PEA) out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). Paramedics are not supported by Resuscitation Council (UK) (2015) or local guidelines to withdraw resuscitation in patients showing PEA, and patients are routinely conveyed to hospital. Locally, only SCAs are authorised to withdraw resuscitation.

Therefore, cessation of resuscitation forms completed by SCAs will be retrospectively analysed to investigate commonalities of patient and system factors; this will be followed by interviews with SCAs to explore how these factors determine futility decisions. The research study aims to improve the management of PEA OHCA where inefficacious resuscitation is recognised early and paramedics are empowered to make autonomous best interest decisions, to improve patient care.

Role of professional paramedic engagement in novice research

Professional paramedic engagement encompasses the consultation of practitioners within their area of expertise, who provide early and essential critical value and propose changes in study projects to improve research outcomes (Pandi-Perumal et al, 2015). In addition, to ensure an effective research agenda within paramedicine, the engagement of professional paramedics is required (O'Meara et al, 2015). Furthermore, engaging professionals means better-quality research will be produced as they will provide a unique perspective with direct knowledge and experience to guide a more relevant and responsive evidence base (Esmail et al, 2015).

However, despite evidence suggesting that professional engagement is vital for robust, credible and contextual research, evidence to demonstrate how engagement improves the research process is limited (Goodman and Sanders Thompson, 2017). Yet, as researcher and paramedic Scott Munro (2016) noted, peer support encourages collaboration, and the sharing of ideas further drives improvements in paramedic research while overcoming the isolation that can be felt during research work.

It was hoped that, by engaging paramedics as experts, learning partnerships would be encouraged and, by sharing knowledge, potential barriers in the research design would be identified early. These would improve the research methodology, study outcomes and the dissemination of findings (Renedo et al, 2015).

Engagement design: expert paramedic engagement in practice

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was not required as paramedics were engaged as professional advisers, providing knowledge based on their expertise in research planning and design (National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), 2014).

Effective engagement strategy: analytical-deliberative model

A lack of tools to measure the effectiveness of professional engagement has been reported (Cottrell et al, 2015). Therefore, to ensure an effective engagement strategy, the analytical-deliberative model was applied (Deverka et al, 2012). The model encompasses: input of values; research and professional experience; methods; facilitated professional interviews and outputs; study design; and implementation strategies. Finally, the engagement outcomes are intended to improve knowledge for novice paramedic researchers by identifying improvements in research design using the expertise of research paramedics and paramedic clinical academics.

As the data gathered in professional engagement are qualitative, the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative interview research (COREQ) 32–item checklist was also applied (Tong et al Craig, 2007).

Theoretical perspective

Professional engagement sits within a relativist ontology where answers depend on knowledge (Clarke and Braun, 2014). Relativism encompasses the interpretivist epistemology from knowledge that is developed from the subjective meaning of experience (Creswell, 2014). The engagement is underpinned by interpretivism—a social scientific approach which uses semi-structured interviews as a method to explore expert opinion (King and Horrocks, 2010).

Recruitment of expert paramedics as stakeholders

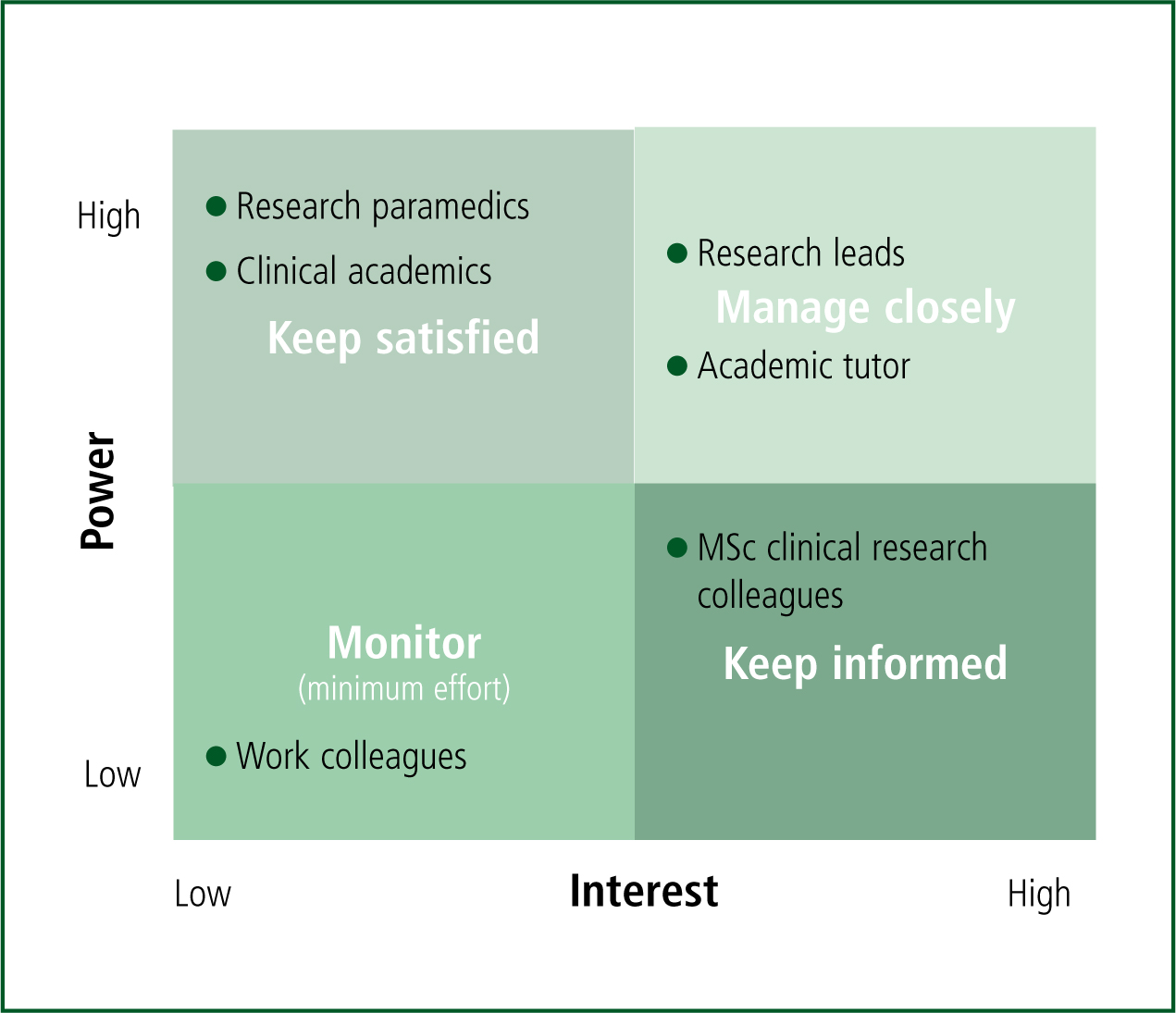

Stakeholder analysis was undertaken to identify key paramedic professionals able to provide an alternative perspective and facilitate improvements to the proposed research design (NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (NHS III), 2010). Stakeholder mapping involves identifying who has an interest or influence, prioritising stakeholders and understanding how best to engage them (Thompson, 2014). The stakeholder mapping results are illustrated in Figure 1.

High power and highly interested people with paramedic experience and research expertise were identified as the most pertinent professionals to engage (NHS III, 2010). Both research paramedics and clinical academics are experienced and so able to inform the proposed research design by addressing the research question, developing methodology and supporting the application of results (Keown et al, 2008). For the purpose of this professional engagement, patient and public involvement was undertaken in a separate exercise, while all other stakeholders were kept informed but active participation of low power and low interest colleagues kept to a minimum (Thompson, 2014).

Stakeholder mapping guided a purposive sampling of five research paramedics and five paramedic clinical academics to provide feedback on the proposed research design, contextual to paramedicine (Esmail et al, 2015). The paramedics were emailed an information sheet to ensure the proposed research project and professional engagement exercise was fully understood. The information sheet also contained five questions based on the proposed project design (Box 1). An interview reminder was sent 1 week after the initial invitation to encourage a participant response (Sappleton and Lourenço, 2016).

Data collection methods: email interview

Given the time constraints and varying geographical locations where paramedics work on shifts, email interviews were selected as an appropriate online communication platform to enable participants to complete the questions at their convenience (Burns, 2010).

Online interviews are challenging to facilitate as there is less face-to-face interaction (Clarke and Braun, 2014). In addition, termination of resuscitation decisions for patients are subjective and sensitive as ethics surrounding decisions by paramedics in the prehospital period are multifactorial and challenging (Erbay, 2014). Therefore, the advantages of email included an empowered interviewee narrative, where participants had the freedom to express self-reflective views without embarrassment of social conflict (Roller and Lavrakas, 2015).

Confidentiality and consent

Confidentiality and anonymity assurances were maintained throughout the interview process (Kaiser, 2009). Consent was explained using the information sheet and confirmed by the return of interview questions (Molyneux and Bull, 2013). Additional consent was gained regarding the publication of results, with paramedics able to withdraw their answers until the results are written.

To gather experience, knowledge and opinions to inform the professional consultation, a non-random, expert purposive sample was used (Palinkas et al, 2015). Five research paramedics and four paramedic clinical academics agreed to participate, returning the interview questions by email. The participants are collectively termed the paramedic engagement group. The group's demographics are shown in Table 1.

| Professional | Clinical academic | Research paramedic |

|---|---|---|

| Role | Paramedic education researcher | Paramedic researcher |

| Mean age (years) | 49 | 39 |

| Mean experience (years) | 25 | 16 |

| Female | 1 | 3 |

| Male | 3 | 2 |

All paramedics were questioned further on their answers. Additional questions were asked to increase depth of understanding, as illustrated in Box 2. Email conversations took place over 1 week.

Analysis of interview answers

As the interview information was qualitative, content analysis was used to preserve the meaning held within the data, which enabled robust data organisation, identification of elicited meaning and conclusion formation (Bengtsson, 2016). Inductive reasoning was applied, allowing the interviewer to collect data with an open mind and identify meaningful answers to draw conclusions to address the design questions (Wood and Welch, 2010).

Findings are based on interview transcripts, and content analysis decontextualisation identified 391 codes. During contextualisation, three codes were disregarded in line with Bengtsson's (2016) recommendations, as they were incongruent to the main themes. Recategorisation condensed the codes into five themes. Peer-review coding and auditable relabelling of codes was conducted during the compilation phase to maximise credibility and dependability of the analysis (Carcary, 2009).

Reflexivity and concepts of trustworthiness

Self-reflection in research planning and analysis is essential to minimise bias (Bengtsson, 2016). On reflection, a female paramedic studying for a master's degree in clinical research who undertook the professional engagement, acknowledged that bias may occur based on previous clinical experience and by undertaking the masters programme (Clarke and Braun, 2014). However, reflexivity was assured by bracketing assumptions to minimise influencing analysis (Fischer, 2009). Data dependability was maintained by using audit to track relabelling and code changes (Bengtsson, 2016). Confirmability was verified through ensuring findings were shaped by the paramedic engagement group by independently cross-coding data (Gale et al, 2013).

Results: themes identified

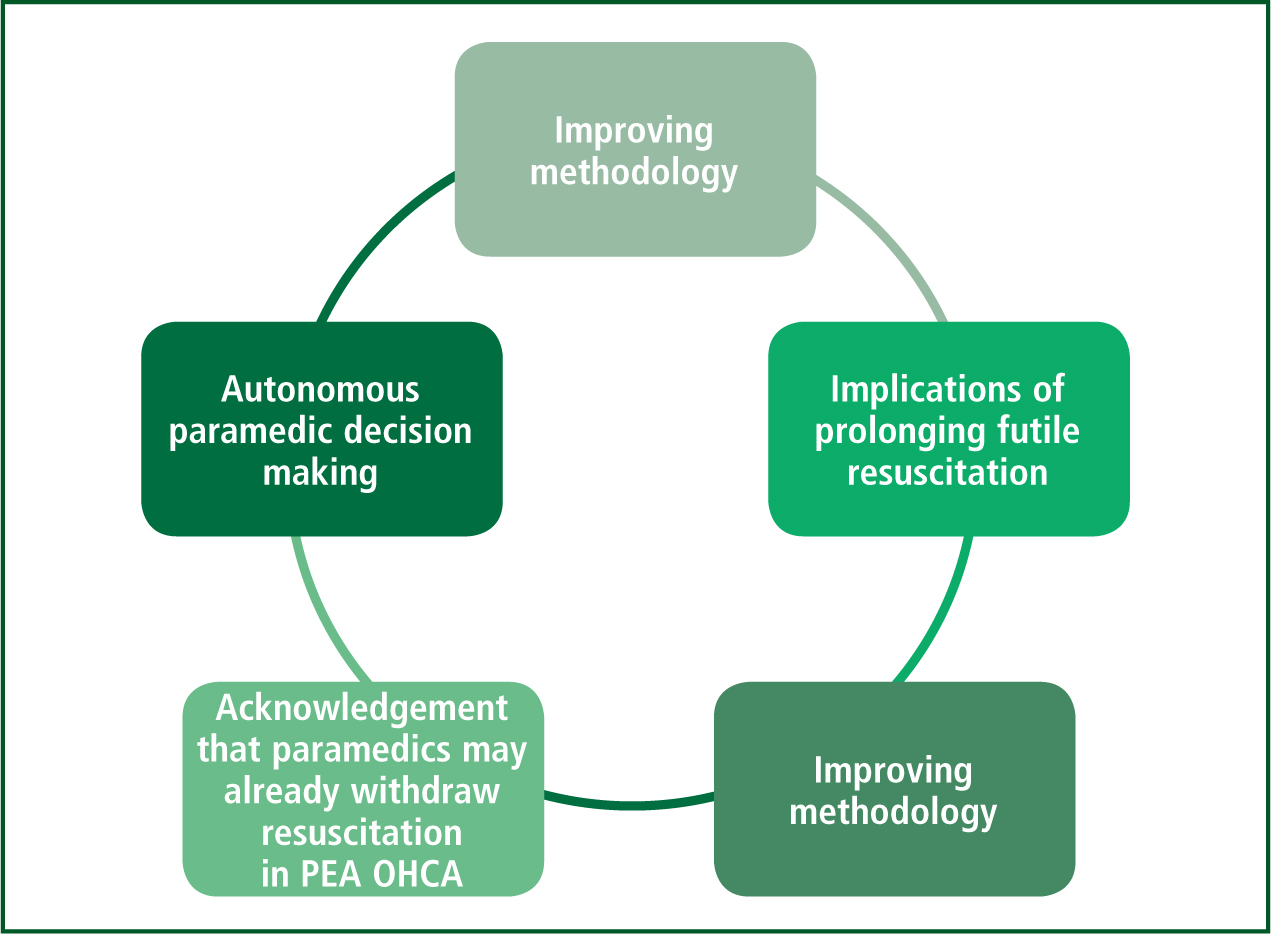

The aim of this paramedic engagement exercise was to gain professional-led experience and views to identify areas of improvement in the conduction of a mixed-methods study in order to maximise the overall quality of the research design (Brett et al, 2014). The paramedic engagement group identified five themes:

The themes identified as engagement outcomes are outlined in Figure 2 and described in Tables 2–6.

| Advantage | Limitations | Data collection |

|---|---|---|

| Influencing factors: ‘This data could provide a useful backdrop to the qualitative findings to demonstrate what factors influence a successful/unsuccessful outcome in OHCA alongside paramedic perceptions regarding these based on their experiences.’ | Complex decision making: ‘Clinical presentation on a tick box cessation resus form may not capture the complexities in decision making made by the clinician.’ | Reflexivity: ‘Personally, I think that with the qualitative element exploring an emotive subject, you would elicit a more data-rich perspective from 1:1, face-to-face interviews. That way, you would be able to be reflexive in exploring different or emerging avenues of questioning that you hadn't been aware of.’ |

| Ethics | Best interest decisions | Futile | Limitations of TOR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Witholding resuscitation: ‘This raises the spectre of ethics: can we or should we withhold resuscitation in PEA? I believe that, unless there is a real chance of treating the cause of PEA, we should withhold resuscitation.’ | Early termination of resuscitation: ‘I think there is also a case, based on my experience, for stopping resuscitation attempts much earlier where it becomes apparent that key factors that contribute to a successful outcome, such as a witnessed arrest, a very short time from call to arrival, good-quality bystander CPR and/or community defibrillation, are not in place. This should be particularly considered when these factors are absent and the presenting rhythm is PEA.’ | Barbaric: ‘Often the patient is at an advanced age and clearly in such poor health that resuscitation is obviously futile and is so fragile of body that continued resuscitation seems barbaric.’ | Bias: ‘Such feelings could lead to bias if we allowed them to affect our implementation of the clinical guidelines for cardiac arrest.’ |

| Recommendations | What is appropriate |

|---|---|

| Capture attention: ‘Perhaps a more condensed title (see example below) might read/capture attention better.’ | Project aim: ‘I think the title of your project works well, it makes good sense and the method (mixed) sits well with the aim.’ |

| Terminology: ‘In your title, you mention senior paramedics and in the introduction you mention senior clinician—both would be different within your inclusion/exclusion criteria.’ | Contemporary: ‘The title of the project is contemporary and relevant, with a mixed-method design being appropriate for the research question.’ |

| Termination of resuscitation applied by some paramedics | Flexibility to adapt study |

|---|---|

| Autonomy: ‘Resuscitation will be ceased if I feel the patient has no hope of survival.’ | Autonomous decision making: ‘I really like the idea of your resuscitation and presume you have looked at this already, but I wonder how many paramedics are choosing to stop resuscitation with a patient in PEA. I am not too sure your title gives you the flexibility to adapt if you discovered that they weren't.’ |

| Decision making: ‘Often we seek remote senior clinician support for a decision which has essentially already been decided by the clinicians present at the resuscitation attempt.’ | Research gaps: ‘I do wonder how often crews stop a non-traumatic PEA resus. I would have thought that although the patient may experience a PEA arrest, resus is often stopped after the rhythm has changed to asystole.’ |

| Terminology | Why? |

|---|---|

| Context: ‘The term senior paramedic leaves scope for confusion regarding the context that these decisions are made in. It might be worth adding “on call”.’ | Ill-conceived fudge: ‘The solution of giving a group of on-call senior paramedics scope to terminate such resuscitations over the phone seems like an ill-conceived fudge.’ |

| Clarity: ‘Clarity about which staff members constitute the senior clinical team would be useful.’ | Decision making: ‘Often, we seek remote senior clinician support for a decision which has essentially already been decided by the clinicians present at the resuscitation attempt.’ |

| Recognised term: ‘Perhaps this is not actually a question for the title, but I wondered about the term senior paramedic. Is this a recognised term you have taken from somewhere?’ | Paramedic autonomy: ‘On a personal level, I feel a greater emphasis could be placed on allowing paramedics (especially specialist/advanced paramedics) to be given autonomy to terminate resuscitation attempts based on their own clinical judgment.’ |

Proposed research study title

The majority of the paramedic engagement group felt the study title was too long and did not accurately describe the study. Alternative titles were suggested along with recommendations on the benefits of using plain language to orientate readers.

Withdrawal resuscitation by paramedics

The paramedic engagement group identified that, in some circumstances, operational paramedics may withdraw resuscitation in PEA OHCA without the support of an SCA. The withdrawal of resuscitation in patients with PEA OHCA may reduce the flexibility of the proposed study, as the design considers decisions made by SCAs only. Therefore, clarity of study inclusion criteria was recommended with clearly defined outcomes.

In addition, the study should acknowledge that the cessation of resuscitation criteria applied by SCAs was to be investigated as well as how futility decisions based on evidence were made.

Implications of prolonged futile resuscitation in PEA OHCA

The term futility was discussed at length and the paramedic engagement group were extensively questioned on their views of how to describe the situation where a patient receives resuscitation with no hope of survival. The group felt that the term ‘futile’ was appropriate and less severe than ‘pointless’ or ‘hopeless’. They expressed their support for operational paramedics making ‘on scene’ decisions, and seeking senior clinical support when required.

Remote SCA decision-making was challenged with the following reasoning. The paramedic engagement group questioned that if SCAs can make futility decisions, why ‘on scene’ paramedics were not empowered to withdraw resuscitation when they had already recognised futility.

Autonomous paramedic decision-making

The paramedic engagement group reinforced the need for further research into futility decisions in patients experiencing PEA OHCA. The research area is relevant to paramedic practice and much needed given the absence of robust guidelines on termination of resuscitation. Ethically sound decision-making was seen as vital, with the acknowledgment that patients with PEA do survive, so the research question must be addressed using a clear, unbiased approach. The importance of reducing undignified patient care, reducing stress and anxiety for family and friends and the psychological welfare of paramedics who resuscitate in knowingly futile incidents were highlighted.

Improving the research methodology

A mixed-method study design was confirmed as appropriate to answer the research question. Mixed methodology was also agreed to be a contemporary design with a pragmatic approach towards evolving prehospital research.

The paramedic engagement group noted that the cessation of resuscitation forms used by SCAs use tickboxes and essential data may be missed, introducing bias. It was suggested that patient clinical records were used to support data collection but bias involved when using retrospective data must also be recognised and planned for to ensure study validity.

Proposing email interviews for the SCA team was met with mixed views. A number of paramedic engagement group members felt that email was a limitation as there is no personal connection. Conversely, others thought email was empowering, convenient and free from social expectations and bias. Therefore, a range of interview platforms were recommended, with the paramedic engagement group suggesting an option of face-to-face, telephone, Skype and email interviews, with the limitations of each acknowledged.

Professional engagement outcomes: value to a novice researcher

Engaging research paramedics and paramedic clinical academics means that clear, concise guidance was provided in the development of a research proposal to be undertaken by a novice researcher.

The email interview response rate was excellent and the answers provided were in depth and full of contextual knowledge, underpinned by paramedic and research experience (Morton et al, 2012).

The paramedic engagement group who took part were keen and willing to share their knowledge and lessons learned through their research experience. Importantly, they confirmed an established consensus, which is often a challenge within stakeholder engagement (O'Haire et al, 2011), in support of specific prehospital research surrounding the current management of PEA OHCA resuscitation.

Gaining professional paramedics' views on the study rationale confirmed the research area as highly relevant and contemporary to paramedicine, while identifying the limitations of current practice (Esmail et al, 2015). The responses from the paramedic engagement group suggest that PEA OHCA is an emotive subject, with strong beliefs surrounding patient dignity which are influenced by practitioners' clinical practice and experience.

The research paramedics and clinical academics applying their clinical experience and research expertise facilitated a number of fundamental improvements in the design of the research project.

Understanding the project design from a paramedic perspective enabled relevant feedback to be made on the research title and the acknowledgement that current practice may occur outside clinical guidelines. Limitations of the proposed methodology, bias and validity when collecting and analysing retrospective data and limitations of the proposed interview strategy were also identified.

Recognising limitations within the proposed study design ensured appropriate revision of methodology to benefit the overall quality of the project (Pandi-Perumal et al, 2015). To address limitations, the paramedic engagement group proposed practical solutions, including the development of robust inclusion and exclusion criteria reflective of the data required to address the study question. In addition, diverse data collection methods were used for interviews to give participants choice and fit around work commitments.

The paramedic engagement group also challenged the autonomy of operational paramedics and the impact and implications of prolonged futile PEA resuscitation. Contextual factors around these themes were highlighted and this in turn provided a holistic, paramedic-led approach to orientate and improve the overall research design (Esmail et al, 2015).

Limitations to engaging paramedics as experts

Measuring the impact or effectiveness of professional engagement is challenging (Cottrell et al, 2015). A literature review on stakeholder engagement in research found limited evaluation measures on the effectiveness or long-term effects on healthcare research and outcomes (Esmail et al, 2015). Additional limitations were noted by O'Haire et al (2011), who describe a lack of stakeholder engagement methodology; small samples size that limited perspective differences; an inability to reach a consensus; and the lengthy amount of time required to engage stakeholders.

Professional engagement, although there is evidence that it applies qualitative approaches (Rhodes et al, 2014), lacks rigorous evidence underpinning robust evaluation of its effectiveness (Esmail et al, 2015). That said, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) presents an evaluation framework assessing the short and long-term effects of engagement (Forsythe et al, 2018). However, PCORI is said to be used intermittently and is not compatible with the principles of evidence-based practice.

Esmail et al (2015) suggested use of the consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT), a 25–item checklist which focuses on the design by analysing and interpreting studies to improve the quality of reporting and assist researchers in professional stakeholder engagement.

However, no measure of effectiveness for stakeholder, specifically professional engagement, is available. The limitations of this are acknowledged and the findings should be interpreted accordingly.

Summary

The findings provided by the paramedic engagement group are embedded in the research design of the PEA OHCA study, improving its overall design quality. Paramedics, as professional stakeholders, understand the multifactorial complexities of prehospital ambulance research, and can provide pragmatic solutions for limitations. That said, because of the lack of tools to demonstrate the effectiveness of professional engagement, the extent to which it benefited the research proposal cannot be measured.

Novice researchers within paramedicine would benefit from early collaboration and engagement of research paramedics and clinical academics in the design of their research proposals, providing direction on methodology, identifying limitations and bias, and contributing to improve the overall quality of the study.

For a novice, professional paramedic engagement also provides valuable opportunities to gain experience in email interviews, communication and use of research terminology. Novice researchers can gain knowledge by seeking advice at an early stage from expert stakeholders within their field of clinical practice. This provides an excellent opportunity to collaborate with experienced paramedic researchers, not only learning from their expertise but also embedding their recommendations into practice, providing the novice with guidance and efficacious direction to improve research design specific to paramedicine.