The Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council (PHECC) is the regulatory body responsible for developing guidelines for care provided by ambulance services in Ireland. The PHECC, was established by Statutory Instrument (Establishment Order, 2000) which was amended in 2004 (Amendment Order, 2004).

There are various committees and working groups within PHECC. One such group is the Medical Advisory Group (MAG). This group issue guidelines for use by all approved organisations (statutory, private, voluntary and auxiliary). These guidelines are known as Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs). There are statutory requirements that training be provided and imperatives that CPGs be adapted to reflect advances in cclinical knowledge. Translating advances in CPGs into care delivered to patients poses challenges for the standards bodies and service providers as these advances involve new knowledge and skill acquisition by practitioners and the incremental development of existing expertise. The dissemination of such information to a large professional and voluntary workforce is challenging in terms of developing appropriate educational programmes, employing effective and cost-efficient training methods and ensuring competence. The ultimate goal of education is to enhance patient care through modified behaviour. Training that enhances participant activity and provides opportunity to practice skills has been shown to effect change in professional practice and improve patient outcomes (Davis et al, 1999).

The third edition of the clinical practice guidelines for advanced paramedics (APs) in Ireland was published in 2009 (Pre-hospital Emergency Care Council, 2009) which incorporated significant modification of existing practice and the addition of new skills, medications, and routes of administration. Subsequently, an ‘up-skilling’ process for existing APs was developed and implementation began in June 2010. Recognising that practitioners may have varying learning styles (those who learn by doing, those who focus on the underlying theory, those who need to see how to put their new knowledge into practice, and those who learn by observing and reflecting on what happened) (Honey and Mumford, 2006), the training methods employed included four discrete modalities:

To inform future educational programme development, we determined which teaching method was most effective for medium-term learning from the perspective of AP learners.To do so, a short answer survey was devised measuring the effectiveness and ‘user-friendliness’ of each training method, particularly in relation to self-reported behaviour change.

Methods

Participants

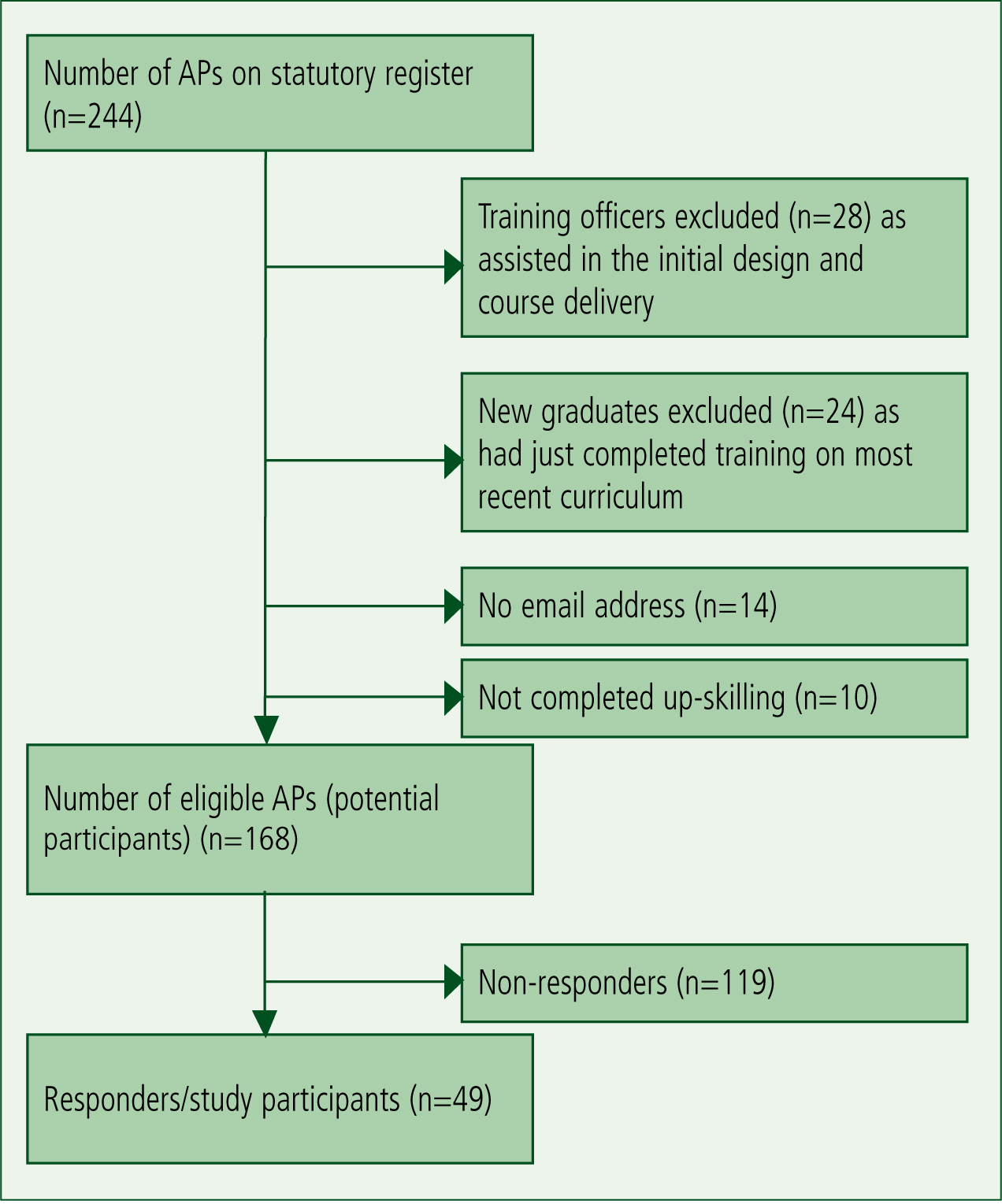

All APs licensed to practice in Ireland are included on PHECC’s register (n=244). An online survey (Appendix 1) was distributed to all eligible APs (n=168) (Figure 1) in April 2011. The survey (previously piloted) was conducted using Survey Monkey™. Participants were contacted via e-mail to participate six to nine months after training was completed. Respondents were provided with a concise and unbiased explanation of the survey. Reminder emails, shown as beneficial in improving survey response rate (Sheehan and Gleason, 2000), were emailed two weeks later. Participation was voluntary and anonymous and all consent was recorded. Ethical approval was obtained from the Education and Health Sciences Ethics Committee in the University of Limerick, and the Research Ethics Committee of the Mid-Western Regional Hospital, Limerick, Ireland.

Analysis

Completed questionnaires were coded numerically and inputted to statistical packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS™ version 14.0) for analysis. Qualitative data, specifically free text comments, were coded line by line and dominant themes identified. The results from the five-point Likert scale were grouped into ‘strongly agree/agree’; ‘neutral’; ‘disagree/strongly disagree.

Self-reported effectiveness was measured based on respondents’ ability in specified clinical scenarios. Such self-assessment is integral to many appraisal systems and has been espoused as an important aspect of personal and professional development as health professionals are increasingly expected to identify their own learning needs (Ward et al. 2002; Colthart et al, 2008).

Results

Respondents

The response rate from eligible participants was 29 % (49/168). The majority of these were male (92 %:45/49) with 36.6 % (18/49) aged between 31–35 years, more than double the number in any other age group, 55 % (27/49) had completed the AP programme between 36–48 months prior, with equal numbers 22 % (11/49) having completed the programme more recently or more than four years previously, 29 % (14/49) of respondents often or always participated in post-graduate education opportunities, while the majority 63 % (31/49) sometimes or only rarely participated. The remaining 8 % (4/49) of respondents had never participated in post-graduate education.

User-perceived attributes of teaching and assessment methods

Responses regarding user-friendliness were divided into the positive and negative feedback received for each of the teaching and assessment methods employed in the programme, how these integrated with learning styles, and whether the respondent felt that they were fit for purpose. Collated results are shown in Table 1. In summary, respondents believed that neither reading only nor practical only learning provided all of the required information. However, all stated that practical learning was easier to understand and was an important part of the learning process, while 98 % (45/46) stated that practical learning was most suited to teaching of skills and for holding their attention. In contrast, 35 % (17/48) of respondents believed they were easily bored or distracted when reading learning material, but stated that reading material was an important facet of learning (94 % 45/48) and that the material was a useful resource to reference following completion of the programme (79 %: 38/48). Similarly, respondents indicated that both written (workbook) and scenario-based assessments were appropriate for both learning (83 %: 38/46 and 88 %: 38/43, respectively) and evaluation of knowledge (77 %: 36/46 and 89 %: 40/45, respectively). However, scenario-based assessment was clearly seen as best for determining skill proficiency (20 %: 9/46 written vs 89 %: 40/45 scenario-based, respectively).

| Reading | Practical learning | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive attributes | ||||

| Enjoyable | 35/48=73 % | 44/46=96 % | ||

| Easy to understand | 29/48=60 % | 46/46=100 % | ||

| Easy to use | 39/47=83 % | 44/46=96 % | ||

| Negative attributes | ||||

| Easily bored or distracted | 17/48=35 % | 1/46=2 % | ||

| Difficult to understand | 6/48=13 % | 2/46=4 % | ||

| Difficult to remember | 39/48=81 % | 2/43=5 % | ||

| Too time consuming | 5/48 10 % | 0=0 % | ||

| Integrates with learning style | ||||

| Reading | Practical Learning | Written assessment | Scenario assessment | |

| User takes additional notes | 36/48=75 % | 35/46=76 % | ||

| Acts as a reference later | 38/48=79 % | |||

| Is animportant part of learning | 45/48=94 % | 44/44=100 % | 38/46=83 % | 38/43=88 % |

| Fit for purpose | ||||

| Good for teaching/ assessing knowledge | 33/47=70 % | 42/45=93 % | 36/46=77 % | 40/45=89 % |

| Good for assessing attitude | N/A | N/A | 12/46=26 % | 28/45=62 % |

| Contains all required information | 19/48=42 % | 19/44=43 % | ||

| Good for teaching/ assessing skills | 22/48 = 46% | 45/46=98 % | 9/46=20 % | 39/44=89 % |

Outcome measures: perceptions of short-term and medium-term effectiveness

Effectiveness was determined through self-reported perception of ability. The results for each of the teaching and learning modalities are shown in Table 2. Practical learning through hands-on skills stations proved most effective in both short- and medium-term knowledge and skills retention, with 80 % (36/45) of respondents stating that this was successful in both the short-and medium-term. Indeed, 91 % (42/46) believed that they benefited from their practical instructors addressing their individual training needs, from having more than one instructor available to them (60 %: 27/45), and either from managing a scenario in front of their peers (73 %: 33/45) or from watching their peers manage scenarios (87 %: 39/45) (Table 3). Most importantly, the knowledge acquired during practical learning influenced patient management immediately (89 %: 40/45) and after six months (84 %: 37/44).

| Reading | Practical learning | Written assessment | Scenario assessment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good retention of knowledge/skill (immediate) | 13/48*=27 % | 36/45=80 % | 33/46=72 % | 35/45=78 % |

| Good retention of knowledge/skill (at 6 months) | 21/48=44 % | 36/45=80 % | 15/46=33 % | 24/44=55 % |

| Influenced patient management (immediate) | 37/48=77 % | 40/45=89 % | Question Not asked | Question Not asked |

| Influenced patient management (at 6 months) | 33/48=69 % | 37/44=84 % | Question Not asked | Question Not asked |

* Note: Variations in number of respondents due to the question being skipped/excluded by individuals.

| The manual | n=48 | |

| I enjoy material presented in written format | 35 | 73 % |

| It allowed the individual write additional notes | 36 | 75 % |

| It was easy to understand | 29 | 60 % |

| It was user-friendly | 39 (n=47) | 83 % |

| It acted as a reference resource after completion of the programme | 38 | 79 % |

| Candidates needed to re-read the manual to remember the knowledge | 39 | 81 % |

| Comments: The strengths of the manual were that ‘it was i of text and diagrams’ and the ‘format was interesting and easy to follow’. | ||

| The workbook | (n=46) | |

| The workbook was fair | 21 | 46 % |

| The workbook was unfair | 4 | 9 % |

| The workbook was transparent | 21 | 46 % |

| The workbook was not transparent | 8 | 17 % |

| I liked open-ended questions | 15 | 32% |

| I disliked open-ended questions | 17 | 37% |

| I liked closed-questions | 29 | 63% |

| I disliked closed questions | 1 | 2% |

| Completing the workbook ensured you were prepared for the course | 37 | 82% |

| I would recommend a workbook as a form of assessment | 24 | 52% |

| The workbook was a good method to assess overall learning | 35 (n=36) | 97% |

| Skill Stations | (n=46) | |

| I enjoy practical learning | 44 | 96 % |

| The knowledge is easy to understand | 46 | 100 % |

| The skill stations are user friendly | 45 | 98 % |

| Candidates who write additional notes | 35 | 76 % |

| Small group training assessed individual candidate needs | 42 | 91 % |

| Small group training can be intimidating | 4 | 9 % |

| Two trainers per skill station improved the experience | 34 | 74 % |

| Comments: ‘Very well received’, ‘kept interested’, ‘enjoyed small group teaching and rotating stations’ | ||

| Scenario testing | n=45 | |

| Scenario test was fair | 27 | 60 % |

| Scenario test was unfair | 8 | 18 % |

| Scenario test was transparent | 21 | 47 % |

| Scenario test was not transparent | 10 | 22 % |

| Scenario test was good for assessing simple issues | 37 | 82 % |

| Scenario test was good for assessing complex issues | 28 | 62 % |

| Managing a scenario in front of my peers was a positive educationally experience | 33 | 73 % |

| Watching my peers manage a scenario was a positive educational experience | 39 | 87 % |

| I would recommend scenario testing as a form of assessment | 34 (n=44) | 77 % |

| Two trainers per assessment improved the learning experience | 27 | 60 % |

| Two trainers per assessment was intimidating | 8 | 18% |

| Two trainers per assessment was not intimidating | 30 | 67 % |

| Scenario testing is a good method to assess overall learning | 40 | 89 % |

Comments: ‘It was more enjoyable watching than being watched!’, ‘Excellent’, ‘Being tough replicated real life’, and ‘Some issues with instructors’.

Discussion

There is a considerable incentive to provide training in an effective and cost efficient way: incurred costs include trainer-related costs (development of the educational material, provision of training equipment and infrastructure, opportunity costs due to staff involvement) and trainee-related costs (opportunity costs associated with provision of study time, study materials and maintenance of service throughout training). Learning is a continuous process (Acelajado, 2011) and is not a replication or reproduction of knowledge and skills but an active meaning-making process in which the learner actively engages (Dewey, 1916).

The long-term effect of training on the practitioner’s behaviour is central to this (that is, the reaction of the learners to the process, increase in knowledge, application of this knowledge, and effect on behaviour or practice) (Kirkpatrick D and Kirkpatrick J, 2006). Corporately and ethically, it is not satisfactory to say that personnel were trained and are, therefore, competent. Training must involve the medium-and long-term modification and regular reinforcement of best-practice behaviour.

This study shows that those APs surveyed prefer practical learning and that over 88 % of respondents (38/43) believe scenario testing is important and an effective way of teaching and assessing skills and knowledge. When asked how this type of education impacted on them six months after the programme, 80 % (36/45) believed that practical learning promoted knowledge retention, while 84 % (37/44) believed it influenced patient management and skills.All participants agreed that practical learning is important, with 96 % (44/46) of respondents having enjoyed practical learning.

Of course, varying educational methodologies (including blended learning) may be appropriate for training APs. On-line learning (Ellis and Collins, 2012) and traditional classroom teaching are typical examples that take diverse learning styles into consideration (Fleming and Mills, 1992; Leite et al. 2010) Indeed, research- and evidence– based practice were favoured by paramedics in New South Wales, Australia where 90 % of those surveyed (742/822) believed that pre-hospital research improved patient care (Simpson et al, 2012). High-fidelity simulation, simultaneously assessing cognitive knowledge and field performance, has been used in North Carolina (USA) since 2007, and is used as part of the certification programme for paramedics (Studnek et al, 2011).

Subjective multiple choice and standardised patient assessments underemphasise important domains of professional competence, for example, integration of knowledge and skills, context of care and team working. Assessments, therefore, should foster habits of learning and self-reflection and drive institutional change (Epstein and Hundert, 2002). Studies of continuous medical education (CME) (Davis et al, 1999) suggest that interactive CME sessions which enhance participant activity and provide opportunity to practice skills can effect change in professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Therefore, teaching of clinical skills should include three specific components: learning how to perform certain movements (procedural knowledge); why one should do so (underlying basic science knowledge); and what the findings might mean (clinical reasoning) (Michels et al. 2012).

In Ireland, ‘ambulance training’ of the 80’s and 90’s relied on approaches similar to basic medical education and emphasised rote learning rather than requiring students to understand and to reflect (Kellet and Finucane, 2007).

Limitations

This study has some limitations, namely the subjective self-reporting and self-perceived competence components coupled with the low response rate. However, it is the first study of its kind relating to AP education in Ireland that has surveyed all registered APs, and provides some insight into the preferred learning styles of these healthcare professionals.

Conclusions

This study shows that, in the opinion of the respondents, practical learning and assessment are most effective for short- and medium-term information retention and are most influential on patient care for APs. All participants agreed that practical learning is important, with most (96 %: 44/46) finding practical learning enjoyable.

Subjectively, Irish APs believe that they benefit from this method of training delivery, and that the benefit accrues to the patient in the short- to medium-term at a minimum. This preference should be acknowledged when planning AP-oriented education programmes. Future work may document the educational approaches used in supporting the professional development of pre-hospital practitioners broadly to measure their effectiveness, both self-perceived and impact on practice.