Every year, between 36 and 81 people per 100 000—approximately 60 000 people—are estimated to experience an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in the UK (Noc et al, 2014). Despite a constantly developing healthcare system, the response to and treatment of OHCA have produced consistently poor outcomes in the UK, with an average survival-to-discharge rate of 7–8% (OHCA Steering Group, 2017). While an OHCA may have been previously considered an unequivocally fatal event (Nolan et al, 2012), advances in prehospital and in-hospital experience and capabilities (Noc et al, 2014) mean that, in some instances, long-term patient survival with good neurological function is possible (Nolan et al, 2012; von Vopelius-Feldt et al, 2016).

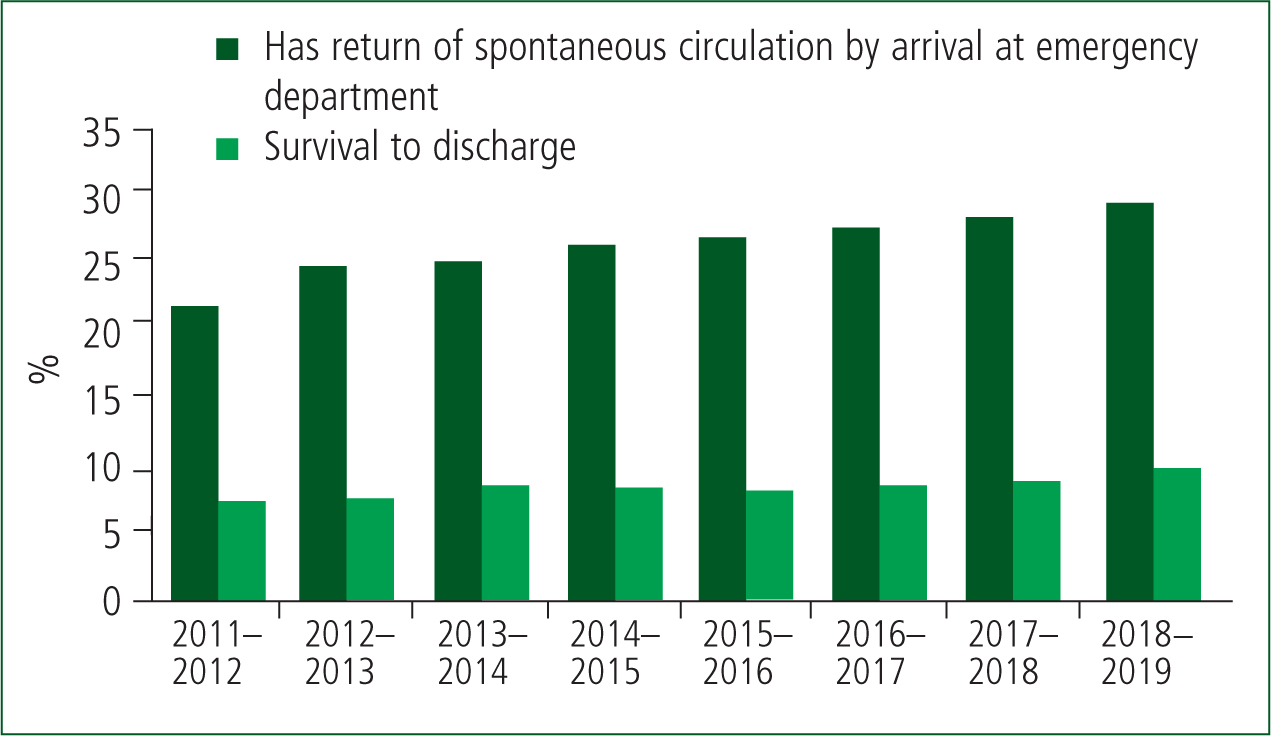

Despite the introduction of a ‘chain of survival’ concept in recent years, and subsequent developments and improvements made to the first three elements (early recognition and call for help, early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and early defibrillation), overall survival-to-discharge rate continues to be approximately 10% on average (Søreide and Busch, 2016); this is further supported by data collected by NHS England (Figure 1) (Keay, 2019). Nevertheless, the chain of survival approach has led to significant changes in local communities, through engagement, awareness and teaching sessions. Furthermore, an increase in community public access defibrillator (cPAD) availability has resulted in significant improvements to the national rate of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) outcomes (Nolan et al, 2015a), despite socioeconomic, cultural, administrative and behavioural challenges (Kim et al, 2017).

In spite of developments in bystander CPR and the prehospital approach to OHCA, a stark discrepancy remains between the rates of ROSC and survival to discharge (Nolan et al, 2015a). While not every patient experiencing an OHCA will survive even with optimum care (Nolan et al, 2015a), concern has been raised over variation between healthcare providers, regions and countries (Miles, 2016; Søreide and Busch, 2016), particularly where there is a healthcare system comparable with that in the UK (Barnard et al, 2019).

Therefore, the purpose of the following analysis is to identify the potential for care pathways, evaluate UK practices and review the evidence for referring patients experiencing an OHCA directly to dedicated cardiac arrest centres.

Methods

With the aim of identifying literature and evidence relevant to OHCA and post-resuscitation care, online searches of PubMed, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) using NHS Evidence, Google Scholar and Summon (University of Bradford) were carried out. The search terms used were ‘non-clinician out of hospital cardiac arrests’, ‘cardiac arrest centres’, ‘OHCA’, ‘OHCA regional centre’, ‘NICE guidelines out of hospital cardiac arrest’, ‘Utstein criteria’, ‘Utstein comparator group’, ‘ACQI’ and ‘ambulance clinical quality indicators’.

When evidence and literature had been identified, the abstract was read to determine relevance and the extent of the findings in relation to OHCA and post-resuscitation care. If considered relevant, from a peer-reviewed source and reliable, the article was sourced using an NHS Athens account. Upon sourcing an appropriate article, a comprehensive review was carried out to identify evidence related to current and developing practices in OHCA care, and further articles were identified from the references listed.

Results

In total, 25 articles were analysed, of which 20 contained significant evidence relating to OHCA practices and post-resuscitation care. In addition, data were collated from NHS England in regards to outcomes and ambulance service performance.

Between April 2018 and January 2019, ambulance services attended 67 430 OHCAs in England at which operational clinicians started or continued CPR efforts on 24 818 occasions (Keay, 2019). As public education and awareness continue to develop and increase, a once-rare possibility is occurring with greater frequency (Stub et al, 2012), with 30.6% achieving ROSC during this time (Keay, 2019).

Survival for patients with issues associated with poorer outcomes is a non-modifiable factor (Mathiesen et al, 2018). To account for such cases, the Utstein comparator group is considered, focusing on those whose survival may be most dependent on the efficacy and efficiency of emergency care delivery—patients who have had a witnessed OHCA with a shockable arrest rhythm where first responders have undertaken CPR (Kay, 2014). Considering the Utstein comparator group therefore offers a more accurate assessment of care delivery in OHCA. However, even when reviewing data produced from the Utstein comparator group, 54.4% of patients had ROSC on arrival at hospital, but only 30.4% survived to discharge between April 2018 and January 2019, according to the data recorded by Keay (2019) (Figure 2).

While developments in the recognition, management and treatment of OHCA may help to improve ROSC and survival-to-admission rates, on average, only 10.2% of total patients who have had an OHCA survive to discharge (Keay, 2019).

NHS England (2018) records the standard of delivery of care by ambulance services using the national Ambulance Care Quality Indicators (ACQIs), which includes a ‘post-ROSC care bundle’. The care bundle sets out the minimum standard of treatment expected in the post-resuscitation phase for ambulance services and clinicians (NHS England, 2018). However, between April 2018, when monitoring of the use of the care bundle began, and January 2019, ambulance services in England applied the post-ROSC care bundle in 58.7% of patients experiencing ROSC, with compliance rates varying significantly between trusts, ranging from 20% in the East of England Ambulance Service to 87% in South East Coast Ambulance Service (Keay, 2019).

Discussion

Current UK practices

Ambulance services across England have to address a range of challenges in their regions, not least the availability of hospitals with a receiving emergency department (ED). In diverse regions with both urban and rural communities, transfer-to-hospital times can vary significantly, particularly when specialist services are required, as can emergency service response times (Mathiesen et al, 2018).

Ongoing reviews and updates by the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC), the increasing number of cPADs, as well as initiatives to increase public awareness and education are enabling communities and ambulance services to be active in promoting and enabling early recognition of OHCA, calling for help, early (bystander) CPR and early defibrillation, which are largely contributing to the increasing number of ROSCs being achieved in the community (Tranberg et al, 2017).

Prehospital factors, including response times, clinical grade and skills, and bystander CPR are considered modifiable, and so have potential for development. Some UK ambulance services have already begun to explore opportunities for improving their response to 999 calls, including the introduction of specialist paramedic resources with enhanced training in critical care, advanced life support and post-resuscitation care, as well as having advanced clinical leadership and experience in the prehospital field, who are equipped to provide advanced clinical decision making and techniques in time-critical cases (Miles, 2016).

Clarke et al (2013) note that high-quality resuscitation involves both technical and non-technical skills, and report that the findings of the TOPCAT2 trial suggest ROSC rates are higher if a specialist clinical resource with advanced clinical leadership and non-technical skills is available. However, as von Vopelius-Feldt et al (2016) state, there is limited evidence to support the findings of Clarke et al (2013), as well as significant variability in the availability of critical care specialists between UK ambulance services. Barnard et al (2019) suggest that the apparently positive impact of prehospital critical care resources may be influenced by the way in which they are deployed, especially if done so with favour towards those triaged as having a greater likelihood of survival or requiring post-resuscitation care.

Regardless of the limited evidence in support of specialised paramedic resources, Dyson et al (2016) recognises the value of experience in clinical decision making and the quality of technical skills, in addition to practitioner exposure to OHCAs. As a result of finding that patient survival is proportional to the volume of OHCA cases that the clinician has attended in the previous 3 years, and that the average exposure is 1.4 OHCAs per year, as well as in recognition of the approach of other healthcare disciplines in appointing specialist practitioners, Dyson et al (2016) conclude by recommending the appointment of specialist clinical resources, including relevant training and development to meet the needs of the role. In doing so, Dyson et al (2016) suggest that the effect of limited experience and exposure can be reduced, as specialist clinicians are more likely to be deployed to cases where they can practise and develop technical and non-technical skills in high-pressure, time-critical situations and consequently improve patient outcomes.

As may be inferred from the significant difference between rates of ROSC on admission and survival to discharge, post-resuscitation care would also benefit from further development.

In the absence of randomised controlled trial (RCT) data to compare performance and outcomes and given that the body of evidence is based largely on care provided in general intensive care, there is little out-of-hospital evidence to support a conclusion that the approach taken by prehospital providers could significantly influence patient outcomes (Noc et al, 2014; Girotra et al, 2015). Nevertheless, systematic and retrospective database reviews, conducted in both the UK and abroad, have provided evidence supporting a multifaceted approach (Nolan et al, 2015a), the use of pathways (Miles, 2016) and having specialist centres that provide enhanced post-resuscitation care, preserve neurological function (Spaulding and Karam, 2017) and implement a standardised approach to post-resuscitation care in a similar manner to the approach taken to major trauma (Nolan et al, 2015a).

Care pathways

At present, paramedics are largely expected to stabilise and transfer a patient who has experienced an OHCA followed by ROSC (Spaulding and Karam, 2017), with Nolan et al (2015a) recommending airway, breathing and circulation stabilisation in the immediate post-resuscitation phase.

The post-resuscitation phase begins when ROSC is established, meaning that, as is increasingly the case, it begins with first responders, whether on scene, in the ambulance or on arrival at hospital (Nolan et al, 2015b). A high proportion of deaths occur in the post-resuscitation phase, according to Girotra et al (2015). Dumas et al (2010) further highlight the importance of this phase, stating that the quality and components of care at this crucial time can significantly influence patient outcome. This is supported by Mathiesen et al (2018), who found that implementing best practice improved patient outcomes. Similarly, von Vopelius-Feldt et al (2016) found that ROSC and survival to admission may be linked to prehospital care, although supporting evidence associated with prehospital post-resuscitation care is limited (Sunde et al, 2006).

Although there is a recommended standardised approach to post-ROSC care and evidence of its positive impact (Sunde et al, 2007), at present, none of the leading UK authorities (Nolan et al, 2015a; NHS England, 2018) appear to specify a care pathway for post-resuscitation patients, except for those with ST segment elevation (STE) showing on their post-resuscitation electrocardiogram (ECG) (Rab et al, 2015). In such cases, direct admission for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is recommended (Søreide and Busch, 2016). Yet, for the significant portion of patients without STE on a post-resuscitation ECG, the approach to post-resuscitation pathway appears vague (Rab et al, 2015). In the majority of regions, the patient will be transferred to the nearest ED for triage and stabilisation (Stub et al, 2012), before further transfer(s) to specialist centres if deemed necessary (Rab et al, 2015).

Although the nearest ED in urban and developed areas will have access to specialist facilities and clinicians, diagnostic testing and intensive care facilities (Dumas et al, 2010), more rural areas and smaller community hospitals will have to transfer patients experiencing OHCA if they need access to cardiac, neurological, anaesthetic and/or intensive care components (Tranberg et al, 2017). In a scenario where all key elements of care are considered time-critical, including on-scene time (Brown et al, 2016), such a response results in significant and often deadly delays in the delivery of definitive care (Stub et al, 2012); this also increases the burden on the local ambulance service, which is relied upon to carry out the transfer, including any specialist equipment and staff, and may face lengthy and even excessive intra-facility transfer times (Brooks et al, 2009). Meanwhile, avoidable stress is being placed on ambulance clinicians, who are responsible for the care of the patient, particularly if they are one of the 33.3% who will die in transit (Spaulding and Karam, 2017).

Several large retrospective studies have also identified the significance of post-resuscitation care, as well as the current high rate of post-ROSC mortality in the UK and worldwide (Stub et al, 2012). In countries with higher overall survival rates, such as Holland (21%) and Norway (25%), the system of post-resuscitation care has a centralised approach, similar to that for major trauma and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (Miles, 2016), in cardiac arrest centres of excellence’ (CACE) (Søreide and Busch, 2016). Patients who have had an OHCA and where ROSC has been achieved and specific, often locally defined, criteria met, are typically admitted directly to the specialist centre, bypassing local EDs, where appropriate (Wise, 2017). In line with national guidance, ROSC patients with evidence of a STEMI on an ECG continue to be admitted directly to coronary angiography or PPCI (Noc et al, 2014), which would ideally also be a CACE.

Direct referrals to cardiac arrest centres of excellence

The approach, supported by the American Heart Association and the findings of the Arizona trial (Girotra et al, 2015), involves the consolidation of services, which limits variation between centres (Wise, 2017), while aiming to increase multidisciplinary, collaborative care (Dumas et al, 2010) with expedient access to a range of interventions (Nolan et al, 2012).

In addition, setting up centres offering experience in providing post-resuscitation and specialist care, such as coronary angiography, can increase a patient's chance of survival (Noc et al, 2014; Storm, 2015), and limit the degree of neurological impairment (Spaulding and Karam, 2017).

In a post-resuscitation care hub within a tertiary centre, the multidisciplinary team will be able to develop experience in dealing with often critically ill post-resuscitation patients (Nolan et al, 2015a), potential complications, including post-cardiac arrest syndrome (Søreide and Busch, 2016), post-resuscitation shock (Noc et al, 2014), and damage to neurological and cardiac organs (Nolan et al, 2015b), and the interventions necessary to provide optimum care (Stub et al, 2012). Such conditions can manifest as seizures, coma, cardiovascular failure, intravascular volume depletion as a result of the body's immune and coagulation response to reperfusion, and death (Nolan et al, 2016). Incorrect or insufficient management of OHCA ROSC patients, both in the hospital and prehospital, can exacerbate the effects, including hypotension, hypoxaemia (Nolan et al, 2016) and hypoglycaemia, emphasising the need for effective and responsive management (Nolan et al, 2012). The measures included in the post-ROSC care bundle address the concerns of Nolan et al (2012; 2016) and provide guidance for managing the impact of post-cardiac arrest syndrome and preventing cardiac arrest from recurring (NHS England, 2018).

Such an approach is already well established with major trauma centres, and has demonstrated a rise in associated favourable outcomes because of the reduction in delays in accessing appropriate care, while providing prehospital clinicians with a clear, uniform care pathway to follow, and removing a degree of ambiguity when time is critical.

Considerations and risks

As has been the case with major trauma and STEMI patients who live in rural and sparsely populated areas, extended journey times and bypassing nearer EDs has been a concern (Tranberg et al, 2017).

According to Stub et al (2012) and Spaite et al (2008), evidence supports the conclusion that the distance from the scene to the tertiary centre does not affect survival rates, while Farshid et al (2015) reports a lower mortality rate for STEMI patients who are diagnosed in the prehospital setting and transported directly to the PPCI centre rather than to the ED even if this is further away. In contrast, Crandall et al (2013) report findings that those with longer travel times have higher mortality rates.

Di Domenicantonio et al (2016) acknowledge the conundrum faced in many prehospital situations, where travel time and access to specialist care often conflict. Despite indication that pathways may improve survival for patients experiencing an OHCA, there is also significant evidence that longer transport times are associated with greater mortality; this is supported by the Scottish Government (2016), which states that rural populations are 32% less likely to survive an OHCA. However, Spaite et al (2008) note a modest increase to transfer time is unlikely to have a significant effect on patient mortality.

Therefore, it is necessary that any model used is responsive to the community in which it is employed, and to identify patients for whom the pathway is appropriate, as well as those for whom the nearest ED would be more beneficial (Dumas et al, 2016). Therefore, intermediary centres, where an OHCA ROSC patient can be triaged and stabilised if necessary before transfer to a CACE, may be of benefit, particularly in more rural areas (Noc et al, 2014). At present, major trauma networks include both major trauma centres and trauma units, which are often on the outskirts of towns and cities, and are a potential operational model to emulate.

In centralising post-resuscitation care, critically ill patients and those at risk of further complications will attend CACEs; this will inevitably lead to a significant rise in patient population in intensive care units and specialist wards in these centres (Nolan et al, 2015a). As these people require close monitoring and proactive management to prevent irreversible ischaemia and dysfunction (Nolan et al, 2015a; Søreide and Busch, 2016), CACEs and local ambulance services will have to determine if centres have the capacity to cope with a larger volume of seriously unwell patients, and what will happen in the event they go beyond capacity.

With increased patient volume come financial concerns, particularly as, in the initial stages of the model, there may be financial implications for the NHS and ambulance services (e.g. for clinician training, equipment, beds and workforce) (Layton et al, 1998). However, Layton et al (1998) state that clinical quality often equates to financial quality, with Weiland (1997) suggesting that care pathways reduce financial impact as well as rates of complications. Nevertheless, Miles (2016) recognises that the initial implications may deter organisations from implementing such a significant change to practice.

If cardiac arrest pathways, models and centres are to be established, the complexities at all levels of care must be acknowledged and addressed, and a multifaceted approach taken to the project. A prehospital emphasis on quality rather than quantity should drive service improvement, while interservice issues can be addressed if prehospital and hospital-based staff develop a positive, close working relationship, and apply a collaborative, multidisciplinary team approach to a model that can significantly improve outcomes of patients who have had an OHCA.

Recommendations

As the research is by no means complete, it is recommended that the components of OHCA and post-resuscitation management continue to be reviewed.

As the UK is a highly populated country, its care providers within and outside hospital can begin to take a proactive approach to the need for improvement in the rate of survival to discharge following an OHCA. From the recommendations, findings and conclusions of previously conducted research (British Heart Foundation et al, 2015) and corresponding ACQI data for ambulance services across England (Keay, 2019), it is recommended that further high-quality research is conducted, preferably an RCT, to determine the feasibility and efficacy of:

In doing this, rates of survival to discharge for OHCA patients who receive standard care at the nearest ED should be compared to those who are referred directly to a CACE.

In addition, it is recommended that the efficacy of training and deploying specialist critical care paramedic resources to OHCA care to provide clinical leadership and advanced skills is evaluated regarding its impact on outcomes and mortality as well as the perceptions of frontline staff.

Monitoring and evaluation

During the pilot phase of any system changes, monitoring can be carried out using pre- and post-change ACQI data, which are routinely collected by NHS England (Kay, 2019). Monitoring these data will facilitate awareness of the uptake of the post-ROSC care bundle within a region in comparison to the national average. Furthermore, comparing data sets should demonstrate any developments in relation to the volume of cases where ROSC is achieved, and the subsequent rate of survival to discharge. Meanwhile, data collected as a part of specialist paramedic audits can also be used to provide further information regarding specific interventions and treatments required, including the use of advanced airway management and procedures.

In addition, monitoring neurological outcomes and time from call to definitive treatment can be done to evaluate the impact of the cardiac arrest pathway, particularly in relation to the proportion of favourable neurological outcomes (Dumas et al, 2010)—i.e. minor or no neurocognitive impairment—and seeking to examine the impact of potential delays from bypassing the nearest ED in favour of a CACE.

Conclusion

Ambulance services across the UK respond to thousands of OHCAs annually and successful prehospital ROSC rates are increasing through public empowerment, education and facilitation, as well as advances in prehospital care. However, the success of such advances has not extended to survival-to-discharge rates, leading to conclusions that post-resuscitation care needs improving.

In light of the successful implementation of centralised care and a multidisciplinary team approach to post-resuscitation care in other countries, such approaches may be appropriate for the UK healthcare system. Not without its challenges and risks, the approach recommended will require a multifaceted approach from prehospital and specialty clinicians, as well as contingency planning because of the vast rural areas covered by UK ambulance services, and further research and investigation, as well as regular evaluation to ensure efficacy and safety.

Nevertheless, it is recommended that steps be taken to explore the efficacy of implementing post-resuscitation pathways for prehospital clinicians through further prehospital research. Furthermore, better use of the post-ROSC care bundle, in addition to a proactive approach to the development of improved prehospital management and specialist resources, will enable prehospital care providers to continue to develop and deliver optimum care to patients who have experienced an OHCA, while remaining current as evidence-based practice continues to advance.