Pelvic injuries have increased in recent years because road traffic collisions (RTCs) have risen (Chesters, 2017). Two-thirds of pelvic injuries are sustained in RTCs, with the remainder caused by motorcycle accidents and falls from heights. Patients with fatal pelvic injuries more than likely die of exsanguination and/or associated severe injuries (Chesters, 2017).

Lee and Porter (2007) undertook a literature review to analyse the assessment and management of pelvic injuries in prehospital situations. They found that mortality rates of patients with pelvic fractures are estimated at between 7% and 19% upon their arrival at hospital, and that mortality rates of patients with ‘open book’ fractures can be as high as 50%. An open book fracture can be defined as any serious fracture that causes the pelvic ring to open like a book. This is commonly seen in anterior injuries because damage to the pubic symphysis can cause the pelvis to open (Gerecht et al, 2014).

Lee and Porter (2007) argue that paramedics can help reduce the retroperitoneal space that a patient can haemorrhage into and therefore lower mortality rates of patients with open book pelvic fractures.

Given the high mortality rates associated with pelvic injuries and the role paramedics can play in reducing these outcomes, the aim of this narrative review is to synthesise literature about pelvic injury recognition, assessment and management in prehospital situations. The authors will also make conclusions on insights or recommendations arising from the review.

Method

The authors undertook a narrative review systematically. The inclusion criteria were UK and international peer-reviewed and published literature, academic papers and grey literature from the only two UK professional journals (Journal of Paramedic Practice and the British Paramedic Journal) for paramedics, as well as the UK Ambulance Services Clinical Practice Guidelines (Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC), 2016) and the Clinical Practice Supplementary Guidelines (JRCALC, 2017). The search covered the period from 2007 to 2017 with some exceptions made for older seminal literature that was highly relevant to the topic. Articles not written in English and not meeting the aims of the review were removed. Table 1 outlines the search terms used.

|

Paramedic

|

AND |

Pelvic injury

|

Fink (2014) argues that literature more than 10 years old is no longer contemporary and should not routinely be included in an academic review as it can diminish credibility.

The academic, peer-reviewed papers were identified using a selection of databases: EBSCO; ProQuest; PubMed; Google/Google Scholar; Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA); British Nursing Index; Scopia; British Library: Springer eBook Collection in Medicine; Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED); Health and Psychological Instruments and Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC).

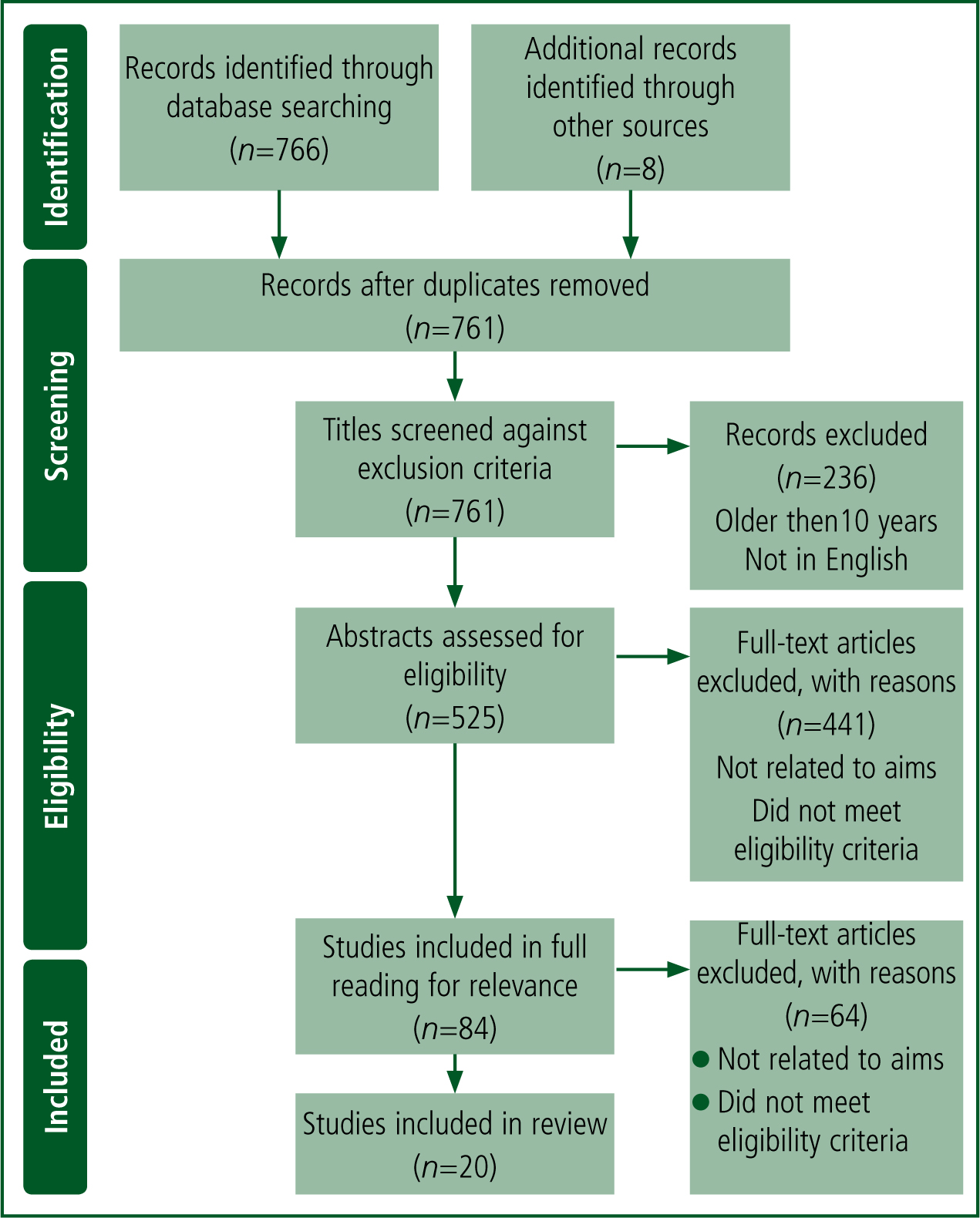

In the initial search phase, duplicate articles were removed, and titles and abstracts from all databases were read for relevance before a more rigorous assessment. In the next phase, the bibliographies and reference lists of the articles chosen were scanned to identify relevant articles not found in database searches. Using this approach, a total of 84 articles were identified as potentially relevant. Once the articles had been read fully, 20 UK and international peer-reviewed and published articles and grey literature pieces were included in the narrative review.

A table of the 20 articles that were deemed relevant for this review was generated (Table 2) along with a PRISMA (2009) diagram (Figure 1).

| Author/date | Aim/s |

|---|---|

| Krieg et al (2005) | To test a pelvic circumferential compression device |

| Papadopoulos et al (2006) | To determine the role of pelvic fractures in auditing mortality resulting from trauma |

| Lee et al (2007) | Guidance on prehospital management of pelvic fractures |

| Giannoudis et al (2007) | To determine the characteristics of patients with pelvic ring fractures in England and Wales, make comparisons to major trauma patients without pelvic injury, and determine factors that predict mortality, including the effect of pelvic reconstruction facilities in the receiving hospitals on outcome |

| Balogh et al (2007) | To prospectively describe the comprehensive pelvic fracture occurrence in an inclusive trauma system |

| Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (2016; 2017) | New guidelines |

| Banerjee et al (2009) | A retrospective analysis over 10 years. Paediatric patients were studied to obtain information on: management of the pelvic fracture, length of stay in the intensive care unit and on the ward, and clinical outcome |

| Williams-Johnson et al (2010) | This review discusses an outline of the current recommendations along with treatment strategies and options in the emergency department, which may vary from institution to institution based on the availability of expertise and resources and because no two trauma patients are alike with regard to the pathophysiology and injury patterns |

| Kirves H et al (2010) | To assess whether staff training and qualifications are associated with accurate prediction of anatomic injury and the completion of prehospital procedures indicated by local guidelines |

| Gabbe et al (2011) | To investigate predictors of mortality following severe pelvic ring fractures managed in an inclusive, regionalised trauma system |

| Cordts Filho Rde al (2011) | To assess whether the presence of a pelvic fracture is associated with greater severity and worse prognosis in victims of blunt trauma |

| Dong and Zhou (2011) | A retrospective review of all patients with open pelvic fractures in an Emergency Department was undertaken to analyse patient management and mortality rates. |

| Fleiter N et al (2012) | A case study is presented to highlight the important of of the correct placement of the pelvic binder for stabilisation of haemodynamically compromised patients |

| Scott et al (2013) | To examine the evidence associated with pelvic binding devices and their application |

| Moss et al (2013) | To outline emerging best practice when packaging prehospital trauma patients while providing spinal immobilisation |

| Helm et al (2013) | To determine the accuracy of prehospital emergency physician field triage in road traffic accident victims. |

| Gerecht et al (2014) | A case study is presented to highlight the appropriate assessment and management of a patient with a pelvic injury |

| Yong et al (2016) | Examination of missed injuries in a physician-led prehospital trauma service indicated that the significant injuries missed were often pelvic fractures. To evaluate prehospital diagnostic accuracy of pelvic girdle injuries, and how this would be affected by implementing the Faculty of Pre-Hospital Care pelvic injury treatment guidelines |

| Lustenberger et al (2016) | This study assesses the incidence of missed pelvic injuries in the prehospital setting |

Findings

Two overarching themes were identified. The first related to issues with defining and measuring mortality rates associated with pelvic injuries. The second theme of assessment and management comprised of the following four subthemes:

Mortality rates

Dong and Zhou (2011) looked at the management and outcomes of open book pelvic fractures. The researchers considered 41 patients who had experienced open book fractures and other, non-specified, traumatic injuries. They measured patients' Injury Severity Scores (ISS) and reported that the higher the ISS, the greater the amount and severity of trauma the patient had experienced. The average ISS was found to be high, suggesting that most patients studied experienced polytrauma.

Mortality rates in people with pelvic injuries remain high despite advances in the assessment and management of these injuries in recent years. This is most likely because of the occurrence of polytrauma, making the identification of open book fractures and assessment of the likelihood of mortality they cause unreliable. To understand true mortality rates from pelvic injuries, only patients with isolated pelvic injuries should be reviewed. Dong and Zhou's (2011) research did not consider prehospital management of the patients as an affecting factor.

Giannoudis et al (2007) compared trauma patients with pelvic ring fractures to those without pelvic injury to determine factors predicting mortality between 1989 and 2001, using prospective data from 106 receiving trauma hospitals in England and Wales (published by the Trauma Audit and Research Network (TARN). In total, 11 149 of 159 746 patients had pelvic ring fractures, whereas 133 486 did not. This study confirmed that patients with pelvic injuries had higher ISS scores of more than 15 (32.1%) compared to 14.4% in patients without pelvic injury, indicating that pelvic injuries are more often associated with other injuries. The authors concluded that early transfer of patients with several injuries, including pelvic, should be considered to improve survival rates.

Similarly, Williams-Johnson et al's (2010) study found that improvements in outcomes for patients with pelvic injuries in the US could be attributed to advances in prehospital and hospital emergency care, interventional radiology, and surgical and critical care. Equally, Papadopoulos et al (2006) performed an autopsy-based retrospective study on 655 patients with a pelvic fracture. Their study highlighted that, although pelvic injuries were not the only cause of mortality, they were a substantial contributing factor.

Studying the management of pelvic fracture among children aged 6–16 years, Banerjee et al (2009) retrospectively analysed patients admitted to a level 1 trauma centre in London over a 10– year period. All patients, who had been evacuated by the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS), were entered into a comprehensive trauma database. In total, 44 patients with pelvic fractures were submitted by HEMS in the 10 years studied, of whom seven died. The most common mechanism of injury was a pedestrian hit by a car, and a stable type of pelvic injury was the most predominant injury. Long bone fracture and head injury were the most common associated injuries. ISS, Revised Trauma Score (RTS) and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) were significantly (P<0.05) altered in non-survivors compared with survivors. Banerjee et al (2009) concluded that, although pelvic fractures in children may have a good long-term outcome, pelvic injuries are a potential indicator of other serious bodily injuries, which carry a high mortality risk.

Balogh et al (2007) in Australia concluded that bleeding is the primary cause of prehospital mortality in all measured pelvic fracture groups. Gabbe et al (2011) highlighted the importance of effective control of haemodynamic instability for reducing the risk of mortality.

In addition, Cordts Filho Rde et al (2011) conducted a retrospective analysis of protocols and records of victims of blunt trauma in a 6-month period over 2008–2009. The patients were separated into two groups: group 1, who had pelvic fracture; and group 2, who were without pelvic fracture. The study was set up to assess whether the presence of a pelvic fracture was associated with greater severity and worse prognosis in victims of blunt trauma. The findings showed that group 1 had significantly lower average blood pressure, higher mean heart rate, lower mean GCS, the highest average Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) in the head, chest, abdomen segments and extremities, as well as a higher mean ISS and lower mean Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS) and RTS on admission. Therefore, it was concluded that the presence of pelvic fracture is a marker of greater severity and worse prognosis in victims of blunt trauma.

Considering these studies, it can be argued that there is a need for rapid, effective pelvic injury assessment and management to reduce mortality rates. This can be considered to be particularly crucial in the prehospital environment as the sooner these fractures are recognised and stabilised, the better the potential outcome will be. Furthermore, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion of patients with pelvic injuries and a high ISS score, which will increase the likelihood of mortality. Further research is required on what prehospital factors are associated with increases or reductions in mortality rates where there is polytrauma.

Assessment and management

UK Ambulance Services guidance

According to the UK Ambulance Services Clinical Practice Guidelines (JRCALC, 2016), prehospital management of suspected pelvic fracture should adhere to the following principles. Any patient found to have a mechanism of injury associated with a pelvic injury and concomitant hypotension must be managed as having a time-critical pelvic injury. These patients should be rapidly transferred to the nearest suitable hospital. The pelvis should be assessed for bruising, bleeding, deformity, swelling and potential shortening of a lower limb. Springing of the pelvis should not be carried out. High-flow oxygen should be administered until vital signs have returned to normal. Additionally, an appropriate splint (binder) should be applied directly to the skin, preferably before the patient is moved. The circumferential pressure from the splint should be applied directly over the greater trochanters. Log-rolling the patient should be avoided and a scoop stretcher should be used to extricate the patient where possible. The patient's pain should be managed using 50:50 mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen or morphine (JRCALC, 2016).

The UK Ambulance Services' supplementary guidelines (JRCALC, 2017) state that tranexamic acid should be administered as soon as possible where there is active or suspected active bleeding.

An improvised splint (binder) can be used if the purpose-made splint does not fit. The pelvic injury should not be reduced beyond its anatomical position. This process should occur on scene as soon as possible and, at most, a 10º tilt should be used while managing these patients.

Finally, clinicians should use intravenous paracetamol as a first-line analgesic and morphine if further pain relief is required, which was an addition in the later supplementary guidelines (JRCALC, 2017).

Log roll and springing

To outline emerging best practice when packaging prehospital trauma patients while providing spinal immobilisation, Moss et al (2013) reported the recommendations of a consensus meeting held by the Faculty of Pre-Hospital Care (FPHC) at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in April 2012, where experienced clinicians from prehospital and emergency care deliberated on the evidence. There is an increasing amount of evidence that movement and changes in patient position and orientation contribute to internal haemorrhage; for example, a fractured pelvic ring can be exacerbated by log-rolling a patient. The patient should be immobilised ‘scoop to skin’ and a pelvic splint should be applied. The recommendation is for minimal handling and one movement so the consensus no longer supports the routine use of a spinal board for spinal immobilisation; a scoop stretcher should be used instead.

Lee and Porter (2007) and Moss et al (2013) agree, proposing that patients with pelvic injuries should not be log rolled because of the risks of aggravating the injury and dislodging any clots, which would lead to further haemorrhage, a higher risk of mortality and additional discomfort to the patient.

Springing the pelvis to assess for pain or deformity had been suggested in the American College of Surgeons advanced trauma textbooks (National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians (NAEMT), 2004); this method is unreliable and leads to clots being dislodged and any injuries being exacerbated (JRCALC, 2016; 2017). Additionally, Lee and Porter (2007) found that springing the pelvis had a specificity of 71% and a sensitivity of 59%. Paramedics should consider the mechanism of injury, and use history-taking and inspection of the pelvis and vital signs as their main assessment tools.

Pelvic binders/splints

A study by Krieg et al (2005) concluded that a pelvic circumferential compression device effectively reduces pelvic ring injuries, and cannot overcompress the fracture, which leads to increased mortality. Case studies such as that by Fleiter et al (2012) support this. A paramedic could use this device to minimise complications. On the other hand, Krieg et al (2005) involved only 16 patients so the results should be used with caution.

The FPHC recommended in 2013 that a pelvic binder should be applied if any one of the following four risk factors is present in any setting where the mechanism of injury suggests a possible pelvic injury. These are where any patient has: a heart rate greater than 100 beats per minute; a systolic blood pressure of <90 mmHg; a GCS Score of 13 or less; and a distracting injury and/or pain on pelvic assessment (Moss et al (2013).

To examine the evidence associated with pelvic binding devices and their application, Scott et al (2013) conducted a literature review, which included the findings of a consensus meeting on the prehospital management of pelvic injuries held in 2012. They conclude that there is no evidence in the literature to help guide a recommendation regarding whether a pelvic binder should be applied before extrication but that it is logical that placement happens before extrication where possible, as the movement of an unstable fracture can disrupt clot formation. They note that this area needs further investigation to identify the optimal method for placement of a binder.

An examination of missed injuries in a physician-led prehospital trauma service found pelvic fractures were often missed. Yong et al (2016) assessed whether the FPHC's 2013 guidelines (Moss et al, 2013) were being implemented and found that of 170 blunt trauma patients, 26 (15.3%) sustained pelvic girdle injury and 45 (26.55%) had a pelvic binder applied, and eight (31%) fractures were missed. Even with a detailed clinical assessment and low threshold for splint application, this study illustrates the problems of distracting injury when trying to diagnose and manage pelvic fractures. The authors found that adopting the FPHC guidelines could have reduced missed injuries from 31% to 8% (Moss et al, 2013).

Triage

Helm et al (2013) carried out a retrospective analysis and comparison of prehospital and in-hospital trauma records of road traddic accident victims treated by HEMS and transferred to a level 1 trauma centre (479 patients). They compared prehospital and in-hospital diagnostic findings according to the AIS to determine the accuracy of prehospital emergency physician field triage in road traffic accident victims. Their results showed that a correct prehospital field triage of patients (by emergency physicians) with an AIS≥3 was achieved of the head 77%; chest 69%; abdomen 51%; pelvis 49%; extremities 70%; neck/cervical spine 67%; and thoracic/lumbar spine 70%. They concluded that accurate field triage in seriously injured road accident victims, even by trained physicians, is difficult. This pertains especially to injuries to the abdomen and pelvis. It is further recommended that, for the field triage, a combination of anatomical and physiological criteria as well as the mechanism of injury should be used to increase accuracy. As pelvic injuries often represent significant trauma and are associated with other serious injuries, these patients should automatically be taken to major trauma centres because of their well-rehearsed trauma protocols and facilities for emergency interventions, critical care and rehabilitation (Chesters, 2017). The authors of this review speculate that if prehospital triage is difficult for experienced HEMS physicians, then paramedics will also find it difficult.

Kirves et al (2010) retrospectively analysed 422 adults with trauma seen by a trauma team to gauge whether the training and qualifications of the clinicians present were associated with accuracy of prediction of anatomic injury and implementation of local prehospital guidelines. To evaluate the accuracy of prediction of anatomic injury, clinically assessed prehospital injuries in six body regions were compared to injuries assessed at hospital in two patient groups: patients treated by prehospital physicians (group 1, n=230); and patients treated by paramedics (group 2, n=190). Kirves et al (2010) found the consistency of prehospital-assessed injury with in-hospital assessed injury was poor in abdominal, pelvic and spinal injuries. Similarly, a study by Lustenberger et al (2016) in Germany found that a significant proportion of severe pelvic fractures were not suspected by the emergency physician at a scene.

Available research data indicate that only a combination of clinical findings can safely rule out pelvic fractures, but these findings cannot often be captured by a short physical examination at the scene of the accident or during transport (Lustenberger et al, 2016). This highlights the importance of early, prehospital mechanical stabilisation of the pelvis for severely injured patients, irrespective of the results of physical examination (Lustenberger et al, 2016).

On the other hand, Lustenberger et al (2016) concluded in their retrospective study of patients with a missed pelvic injury in the prehospital setting that a missed pelvic injury did not significantly affect the in-hospital outcome with regards to mortality and the requirement for an early transfusion. They argued that specifically designed prospective studies to evaluate the impact of ‘missing a pelvic injury in the prehospital setting’ on different in-hospital outcome variables are needed.

Conclusion

The literature confirms that the presence of a pelvic fracture is a marker of more severe injuries and poor prognosis in victims of blunt trauma. It also highlights that mortality rates remain high despite advances in the assessment and management of pelvic injuries in recent years. The high rate of mortality of patients with pelvic injuries is most likely because of polytrauma, as pelvic injuries are often associated with other serious bodily injuries.

Studies in the UK and abroad show that bleeding is the primary cause of prehospital mortality in patients with pelvic injuries, and that ISS—not the type of injury—is the best predictor when determining these patients' mortality.

International research confirms that advances in prehospital and in-hospital emergency care improve outcomes for patients with pelvic injuries. Further research is required on what prehospital factors are associated with increases or reductions in mortality rates where there is polytrauma. Additionally, research is needed to identify the impact of missed pelvic fractures in the prehospital environment.

Distracting injuries are a potential concern when diagnosing and managing pelvic injuries. Accurate prehospital triage of patients with serious injuries to the abdomen and pelvis, even by trained physicians, is difficult. Pelvic injuries are often not the only cause of mortality with these patients. International research confirms that prehospital assessment of blunt trauma is difficult and depends on practitioner skill, and that the consistency between prehospital and in-hospital assessment of abdominal, pelvic and spinal injuries is especially poor. The authors of that particular review speculate that if, prehospital triage is difficult for experienced physicians, then UK paramedics will also find it difficult.

To improve survival rates for patients with pelvic injuries, rapid and effective prehospital pelvic injury assessment and management are needed, as well as early transfer to hospital, preferably to a major trauma centre. Guidelines on how to assess and manage patients with pelvic injuries recommends minimal handling, scoop stretchers instead of long spinal boards, and the removal of clothing when pelvic splints/binders are being placed on patients.

All literature and guidelines are against log-rolling the patient and springing the pelvis when there is a suspicion of pelvic injury; instead, mechanism of injury, history, inspection and vital signs should be the main assessment tools.

Furthermore, there is currently no evidence from RTCs to suggest whether applying a pelvic binder/splint before patient extrication will improve outcomes. However, the authors of this review speculate that the earlier an unstable pelvic fracture is stabilised, the better the outcome will be for that patient. Further research is needed in this area.