Cardiopulmonary resuscitation-induced consciousness (CPRIC) is being increasingly recognised as an issue in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) (Pourmand et al, 2019; Chin et al, 2020; Doan et al, 2020; Singh et al, 2020). Olaussen et al's (2017) Australian registry study showed a 0.7% incidence, with an increase from 0.3% in 2008 to 0.9% in 2014 (Olaussen et al, 2017). Gregory et al's (2021) UK membership survey showed that 57% of UK paramedics reported at least one incident of CPRIC and multiple effects on resuscitation.

No agreed definition of CPRIC exists. However, most clinicians identify CPRIC as consciousness regained to a variable extent while CPR is being performed. Signs range from purposeful movements to more subtle signs such as eye opening or agonal breathing. CPRIC may obstruct CPR, is potentially detrimental to the patient and distracting to practitioners and can be distressing for the patient, practitioners and bystanders.

Identifying CPRIC may allow relevant interventions and optimum CPR to be carried out.

The increasing incidence of CPRIC may be as a result of more effective CPR because of minimum ‘hands-off time’, the introduction of mechanical CPR devices and earlier identification of cardiac arrest (Gräsner et al, 2020).

CPRIC issues can be clinical (e.g. managing an agitated patient, decisions to stop resuscitation) and professional (e.g. the impact on practitioners).

In Ireland, advanced paramedics (APs) are the most senior grade of ambulance service practitioners, and they have comprehensive advanced life support roles and respond to all OHCAs. Paramedics commonly attend OHCAs but do not administer drugs. Emergency medical technicians (EMTs) do not routinely attend OHCAs.

The Pre-Hospital Emergency Care Council (PHECC) is the statutory regulator for prehospital practitioners and publishes all relevant clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) (PHECC, 2017). Medical Oversight (Medico) is a national 24-hour emergency telemedical support unit. Consultation, advice and permissions can be sought by practitioners on dynamic situations where treatment falls outside the PHECC guidelines.

This study aims to explore the CPRIC experience of paramedic practitioners in Ireland as well as their awareness and views on educational and other support needed to deal with the phenomenon.

Methodology

This cross-sectional study included quantitative and qualitative elements with an online anonymous survey of practitioners and a follow-up, confidential, one-to-one semi-structured interview with practitioners who volunteered to take part. There was no patient or public involvement.

An invitation to participate with an introductory letter was distributed to 358 EMTs, paramedics and APs (from the National Ambulance Service, Dublin Fire Brigade and Defence Forces in two regions). Recruitment occurred via work emails distributed by employers. Interested practitioners responded to a dedicated email address.

The anonymous online survey, created using Google Forms, included:

The interviews were transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis, without reaching saturation.

Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel. Research ethics approval was granted by the University College Dublic (UCD) Human Research Ethics Committee (LS-E-20-152-Carty-Bury).

Results

Survey results

Out of the 358 practitioners invited, 232 replied (response rate 64.8%) including 136 APs, 78 paramedics and 18 EMTs from all three organisations. Most participants (81%) were male.

Out of the 232 respondents, 224 (96.6%) reported management of an OHCA (eight EMTs had not been involved); 174/232 (75%) were aware of CPRIC (APs: 91.7%; paramedics: 53.8%; EMTs: 44.4%).

Of the 224 with experience of OHCA care, 73% reported involvement in six or more incidents within the previous 12 months, indicating the cohort had significant recent experience. Of those with OHCA experience, 127/224 (56.7%) said they had witnessed some form of CPRIC, 79/224 (35.3%) said they had not and 18/224 (8%) were unsure.

Of the 145 respondents who had or may have witnessed CPRIC, 76/145 (52.4%) had experienced CPRIC once and 47.6% reported more than one episode.

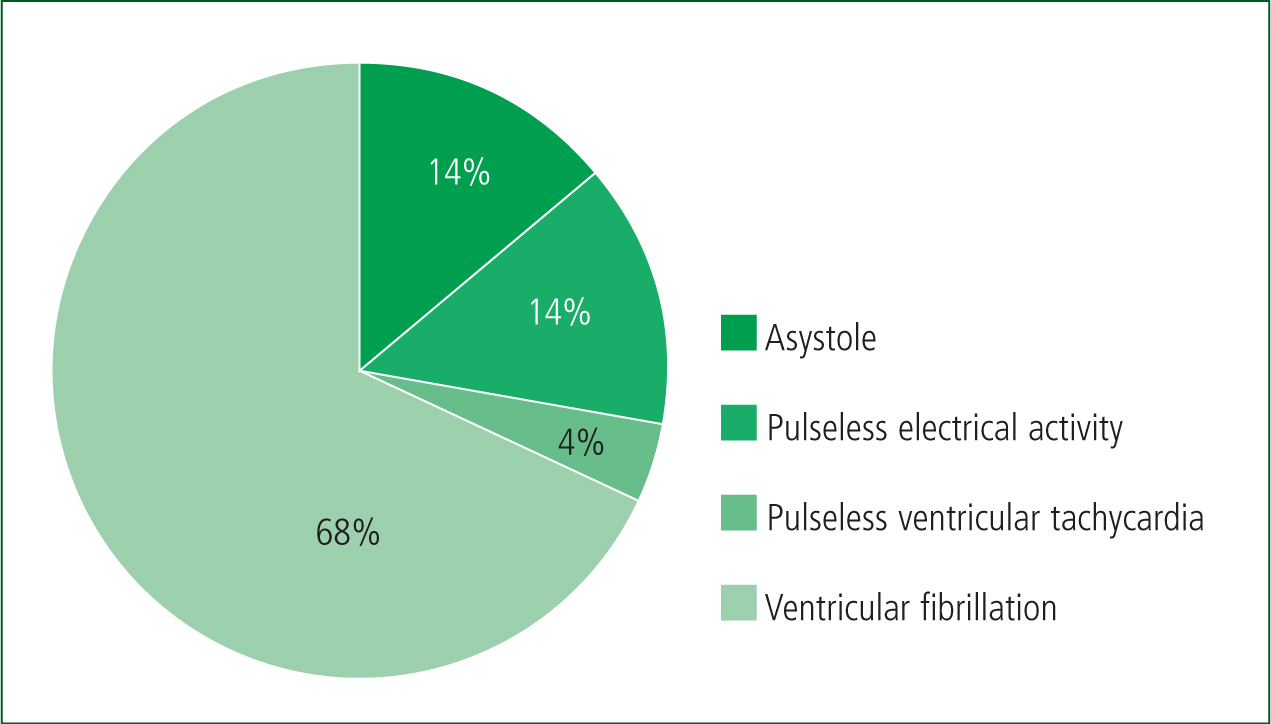

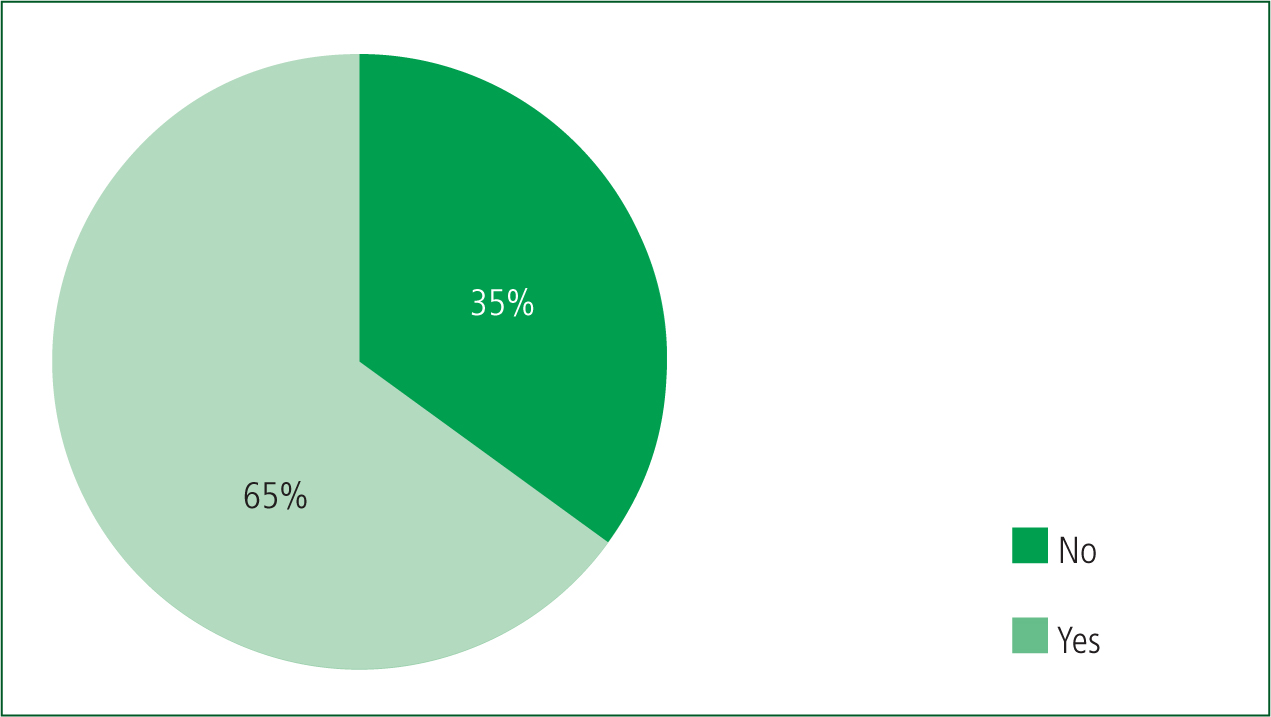

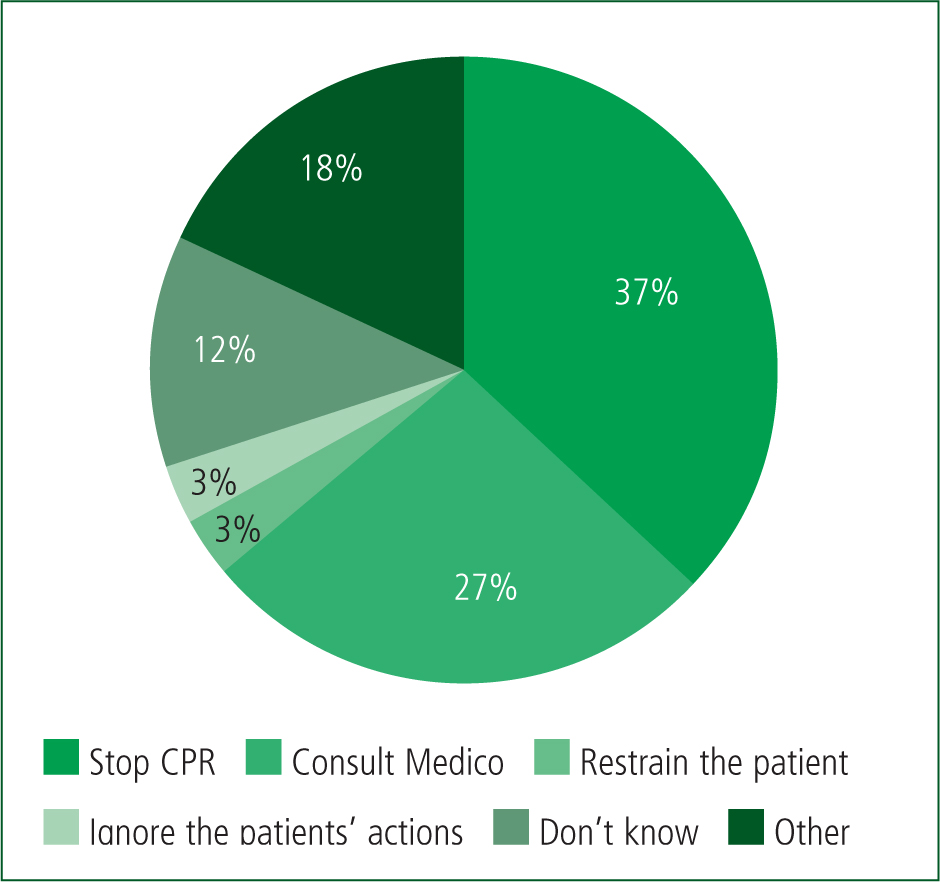

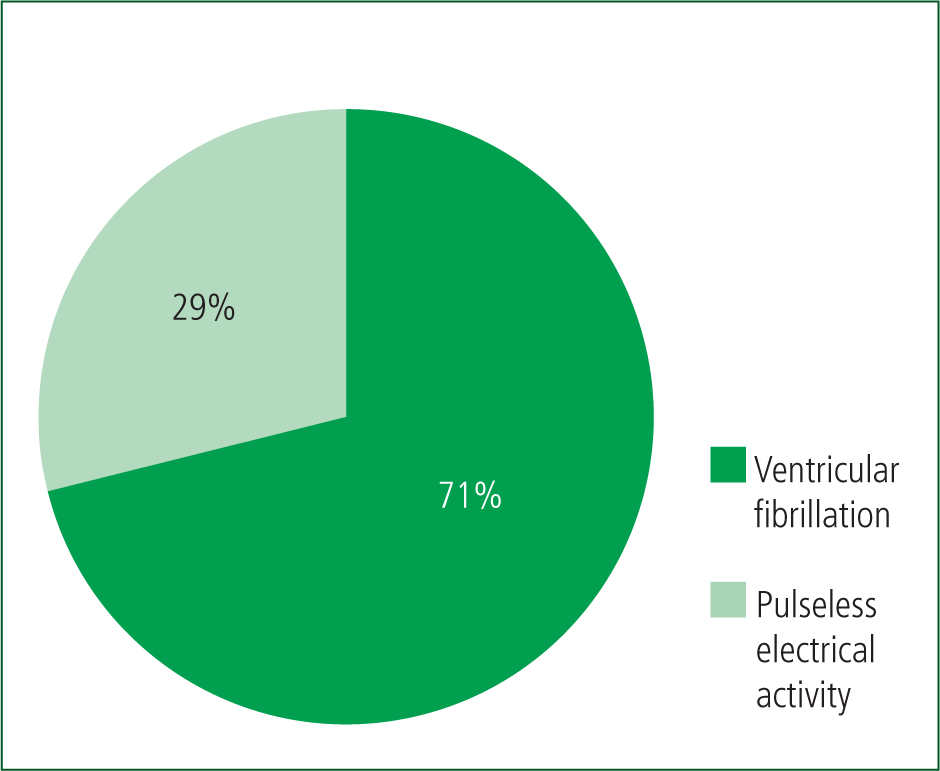

Respondents were asked to comment on the most recent case they had experienced. The initial arrhythmia was predominantly ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (Figure 1); 94/145 (65%) reported that CPR was interrupted at least once because CPRIC features appeared (Figure 2).

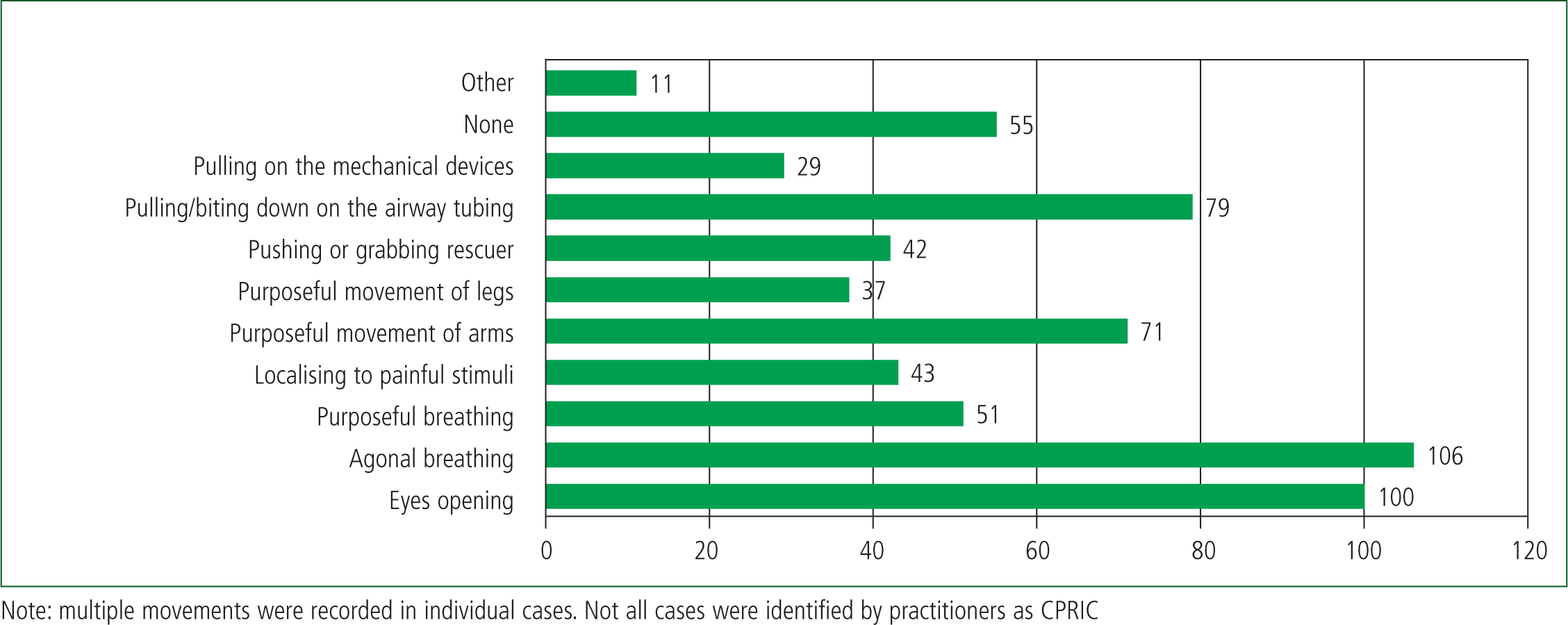

Figure 3 shows reported CPRIC clinical features identified by practitioners. During CPR, 111/145 (76.6%) practitioners reported three or more movements.

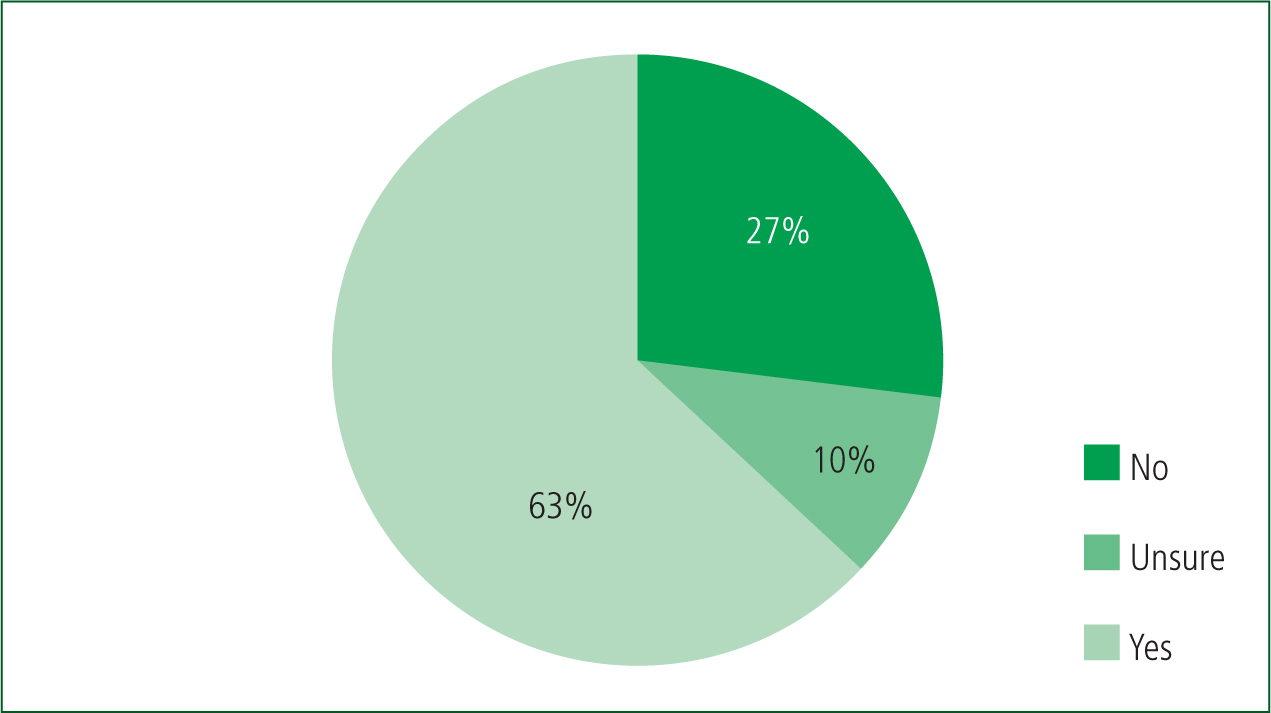

Mechanical CPR devices were in use in 59% of cases (Figure 4). CPRIC cases were managed by patient reassurance (29%), drug therapy (20%), other action (7%) or without any specific intervention (44%); 31/145 (21.4%) of respondents contacted Medico for advice. In 128/145 (88%) cases, the patient was transferred to hospital and in 92/145 (63%) return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) occurred (Figure 5).

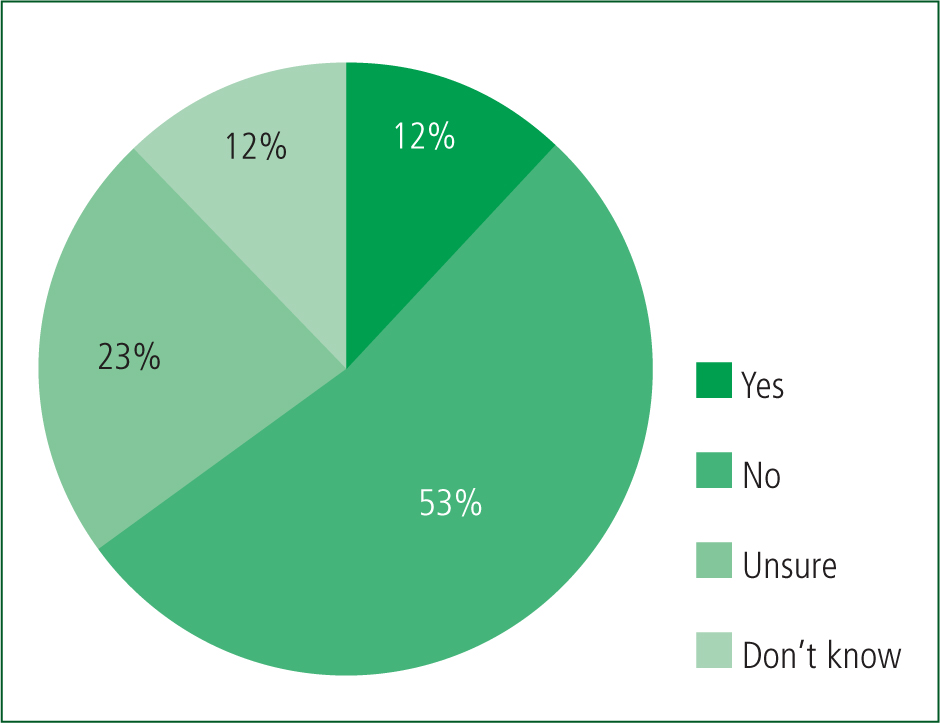

In the three vignettes, practitioners with experience of OHCA were asked about possible actions if CPRIC was witnessed. With signs such as eye opening or breath taking, 65% said they would interrupt CPR outside the recommended times to check the patient (Figure 6). With purposeful movements, 37% said they would stop CPR and 27% would contact the Medico (Figure 7). Finally, if indications to cease resuscitation were present in a patient with CPRIC, 120/224 (53%) said they would not stop and 77/224 (35%) were unsure what action they would take (Figure 8).

Interview findings

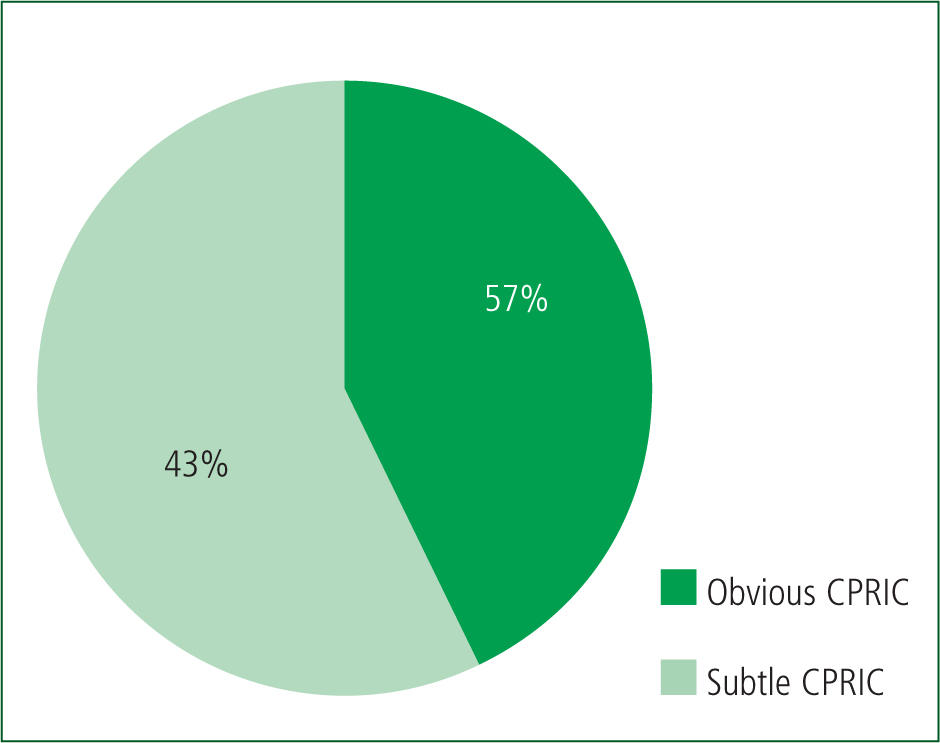

All practitioners interviewed (n=7) had more than five years' experience. Three gave accounts of ‘subtle’ CPRIC and four gave accounts of ‘obvious’ CPRIC (Figure 9).

Six interviews involved adult cases and one interview involved a paediatric case; two patients survived. Themes included: impact on resuscitation; and unfamiliarity with CPRIC/personal perception.

Impact on resuscitation

Recognition

Only two of seven practitioners identified CPRIC during the OHCA:

‘With CPR continuing when moaning and crying started. ROSC? We looked at the screen, VF.’

Five practitioners out of the seven identified what they thought was ROSC at the time but they now believe was CPRIC. It resulted in practitioners interrupting CPR to check the patient multiple times outside the recommended 2-minute cycle.

In one case, a medical practitioner was present on scene, identified the presence of CPRIC and administered drugs; CPRIC stopped in this case with a positive outcome.

Manifestations

CPRIC manifestations included groans, speaking, crying and purposeful movements of extremities, eye opening and breathing.

‘I don't want to die!’

‘She went back to moaning, and crying and shouting – “daddy, daddy!” Still in VF. We shocked her again.’

Of the cases studied, five of seven had VF as the life-threatening arrhythmia and two were pulseless electrical activity arrests (Figure 10).

As the OHCA progressed, some practitioners identified the mechanical CPR device as the reason for the movements because of successful cerebral perfusion; when CPR was stopped, the movements did too.

Potential disruption of resuscitation

‘Subtle’ and ‘obvious’ signs were recorded as occurring while CPR was in progress:

‘Movement of the eyes and head were recorded.’

Practitioners experienced patient attempts at sitting up, pulling/grabbing the mechanical CPR device and tugging at the airway while CPR was in progress both manually and mechanically. Medico was considered by only one practitioner.

In two cases, medication was administered, once by an AP and once by a medical practitioner (midazolam and ketamine in separate cases).

Association with early/high-quality CPR

Non-perfused time was reduced in five CPRIC cases where the patient had received lay CPR/automated external defibrillator use. In the other two cases, the cardiac arrest was witnessed by the EMS crew who initiated CPR immediately.

Unfamiliarity with CPRIC/personal perception

One practitioner, who had identified the mechanical CPR device as being the cause of the patient's return of consciousness during the cardiac arrest, was not aware of CPRIC at the time.

Evidence of CPRIC may be lost because of a lack of awareness. In one case where a practitioner identified CPRIC, another failed to recognise these movements as CPRIC, even though that person had read about such events occurring:

‘There had been a good number of eye movements and even agonal resps. Even as far as a month ago, I had a patient who had his arm twitching.’ To clarify further, the interviewer asked, ‘Was CPR ongoing?’ ‘Yes.’

Impact on practitioners/distress

All practitioners said they found it difficult to explain what exactly had happened afterwards, whether they were handing over to emergency department staff or colleagues on scene or debriefing each other.

‘We were all in a bit of shock from it to be honest.’

‘I was just completely and utterly wiped after that!’

Whether the cardiac arrest involves a child or an adult, practitioners are under pressure from the very moment they arrive on scene. Potential CPRIC events add considerably to those pressures.

Education and guidance

Knowledge about CPRIC came mainly from follow-up research by the practitioners themselves. One said podcasts and further reading provided a basic understanding of the event.

Practitioners all agreed that an educational awareness package and CPGs should be introduced to guide care. There were mixed views over whether there should be a standalone CPRIC CPG; four of the seven practitioners interviewed preferred added direction or some guidance built into the current cardiac arrest CPGs. There was concern among the three practitioners who would like to see standalone CPGs introduced; the current cardiac arrest CPGs are already extensive and detailed, and they feared information could get lost within them.

Educational updates were also suggested to create awareness, perhaps during upskilling days or during the recertification process. All practitioners agreed that treatment/interventions should be considered as part of any guideline development/educational approach.

Discussion

In this study, respondents demonstrated a high level of involvement in the care of people with OHCA, a high level of awareness of CPRIC (75%) and recent experience of at least one episode of CPRIC (57%) —a similar exposure to that reported among UK paramedics in Gregory et al's (2021) study.

Respondents reported a wide range of manifestations and effects of CPRIC; in some cases, these signs led to confusion about the possibility of ROSC and resulted in interruptions to the recommended protocols for CPR, pulse checks or other interventions. In some cases, even practitioners who were aware of CPRIC indicated they may have inappropriately interrupted resuscitation because they believed they may have been witnessing ROSC. During interviews, practitioners reported being confused, shocked and distressed by the phenomenon they were witnessing.

It is striking that 88% of cases were transported to the emergency department and 63% of cases had achieved ROSC at that time; these are far higher figures than normally experienced in Irish OHCA (Health Service Executive, 2020). They demonstrate the apparent association of CPRIC with higher levels of ROSC, probably linked to the high incidence of shockable rhythms—72% of cases reported here were VF or pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

In Ireland, current CPGs make no mention of CPRIC and do not support decision-making in these difficult circumstances. Overall, 21% of practitioners reported contacting the medical support system for advice; however, describing an unexpected phenomenon and seeking advice can be problematic in itself:

‘There was a lot going on—to make a phone call on top of dealing with this cardiac arrest would be difficult.’

Recommendations

This study shows the need for CPRIC educational support for practitioners, for new or amended CPGs to support decision-making and accessing medical oversight; evidence-based guidance on the issue has previously been called for (Rice et al, 2016).

Practitioners should be able to record signs of CPRIC, when encountered or suspected, on patient care records; this is not possible at the moment. Formal recording would allow the national Irish Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Register to evaluate the phenomenon in the prehospital environment.

Better education on CPRIC may prepare practitioners to recognise or suspect CPRIC, to understand its possible association with an increased chance of ROSC and to consider therapeutic interventions.

It is clear from this study that practitioners have difficulties in managing CPRIC and that evidence-based practice is lacking. A CPRIC CPG may support earlier identification of CPRIC, pathways for decision-making and medication, non-medication routes, when to contact medical oversight and when and whether to cease resuscitation efforts. In addition, training and simulation were identified as important initiatives; better knowledge as a consequence may also help establish the extent of the phenomenon.

Some ambulance services recognise CPRIC and have introduced structured components into their CPGs and training programmes (Rice et al, 2016; Ambulance Victoria, 2019; Association of Ambulance Chief Executives and Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee, 2019; NSW Ambulance, 2021).

High-quality chest compressions, defibrillation, advanced life support and treatment of reversible causes remain the priorities for optimal patient outcome in OHCA, and the use of ketamine, midazolam or opiates is recommended by some services to prevent CPRIC from interrupting such care. However, no evidence is available to demonstrate the risks or benefits of such interventions; research in this area is urgently required.

When CPRIC is observed, practitioners are faced with the dilemma of whether to stop or continue CPR while the patient reacts; distress, hesitation and doubt are all reported in this study. No practitioner specifically reported considering the patient's awareness of their surroundings during the event but pain and discomfort were mentioned as potential issues. However, practitioners reported their own distress and raised concerns about the dilemma of ceasing resuscitation if a patient with CPRIC met the technical specifications for cessation. Considerations for upcoming guidance changes from governing agencies including the European Resuscitation Council are required.

Dealing with a patient who displays signs of life during CPR that cease shortly after CPR is stopped requires further guidance. Under current guidance, stopping CPR can be detrimental to the patient's outcome. Recognition of CPRIC is key to the treatment as is the continuance of OHCA protocols for this cohort of patients. As sufficient documented evidence is now showing the prevalence of CPRIC, new in-depth pathways should be considered to it.

A need has been identified for practitioners to engage in a critical incident debriefing with psychological support after encountering CPRIC. This should be addressed by the services involved. Lay and volunteer responders to OHCA are increasingly active and may encounter CPRIC and have similar support needs (Barry et al, 2019).

The pressure to recognise interventions needed and perform them on a person who is perceived to be alive by the public may create unexpected stress, especially when the practitioner is not familiar with CPRIC. Knowledge, understanding and preparation to deal with CPRIC will help both the practitioner and family cope when such an event arises. They may also offer reassurance that the best care is being provided for the patient.

Finally, CPRIC during resuscitation needs more research. Exploration with survivors may yield important insights and reveal a better understanding of the experience.

Limitations

The limitations of this work include its retrospective nature, the potential for recall bias and the need to not generalise beyond the experience of a limited number of services and practitioners.

This work was carried out during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic and all staff were under considerable pressures at the time.

Conclusion

Paramedic practitioners report frequent exposure to CPRIC, which has significant effects on the resuscitation process, on themselves and perhaps on witnesses. Urgent action is needed to address education and awareness needs, guidance on managing CPRIC and better data collection. Research into current and new management strategies should be undertaken.