Stress disorders are conditions preceded and/or triggered by trauma or other life stressors (Song et al, 2019). They can be categorised into primary, which result from direct experience, and secondary, which result from direct or indirect experience over time (Figley Institute, 2012). Each category includes a range of disorders, with primary conditions including acute stress, acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and secondary conditions including secondary traumatic stress, vicarious trauma and compassion fatigue. Related disorders include anxiety, generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and depression. Although there are different criteria for diagnoses (First et al, 2021), symptoms can overlap and causes may be similar.

There are many risk factors known to increase an individual's susceptibility to stress disorders, including genetic and biological factors (Amstadter et al, 2017), personal attributes and traits (Ogińska-Bulik et al, 2021) and specific life events, as recognised by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The DSM–5 lists 17 stressful events that can happen to a person in multiple ways. These can be direct, something they experience personally, or indirect, such as something they witness, that occurs to someone close to them or that they are exposed to as part of their job. Such events include serious accidents, natural disasters, physical or sexual assaults, and other situations that can cause harm and threaten life.

By the nature of their profession, frontline healthcare workers, including nurses, midwives and paramedics, are indirectly exposed to such life events, which might explain why they have a higher than average incidence of stress disorders (Fjeldheim et al, 2014; Wild et al, 2020; Ogińska-Bulik et al, 2021). This is often because of repeated exposure to traumatic events, coupled with occupational stress from factors such as a lack of support and work demands (Fjeldheim et al, 2014; Kerai et al, 2017; Johnson et al, 2020; Peter et al, 2021).

Evidence indicates healthcare students, such as those in the fields of nursing, midwifery, and paramedicine, are also developing stress disorders because of a range of factors including exposure to traumatic events as well as the requirements of clinical practice and their academic course (Fjeldheim et al, 2014; AlFaris et al, 2016; Azizi et al, 2016; Bayri Bingol et al, 2020; Cao et al, 2021).

For healthcare students, developing such disorders could damage both their personal quality of life and their ability to meet academic requirements. It could also affect their clinical performance, which in turn could lead to poorer patient care.

Understanding the global prevalence of stress disorders and associated factors among these students could uncover the extent of them, and determine whether there is a need to implement or improve interventions to reduce the problem.

There have been previous reviews in this area. While some have concerned on nursing or nursing and midwifery students together, none have included or focused primarily on paramedic students, who are also frontline healthcare students.

Tung et al (2018) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the prevalence of depression in nursing students across several countries. Joseph and Devu (2021) reviewed stress and coping among nursing students in India, and Chaabane et al (2021) conducted an overview of systematic reviews focused on the prevalence of stress, stressors and coping among nursing students in the Middle East and North Africa. An integrative review conducted by McCarthy et al (2018) included nursing and midwifery students and focused on stress and coping.

These reviews provided some insight but primarily for single populations of students. This review was intended to capture the prevalence of stress disorders in three populations of students.

The primary aim of this review was to investigate the global prevalence of stress disorders in nursing, paramedic and midwifery students. It also aimed to identify associated factors that may increase or decrease prevalence. Research questions included:

These questions were formulated using the PICO tool, which is used to structure research questions involving evidence synthesis, such as systematic reviews (Eriksen and Frandsen, 2018). PICO stands for: patient/participant/population; intervention (treatment or exposure); comparison/comparator; and outcome (Schardt et al, 2007). For this review, PICO included: population (frontline healthcare students), exposure (to occupational trauma and/or course-related stress), comparator (none) and outcome (prevalence of stress disorders) (Table 1).

| P | Patient/participant/population | Frontline healthcare students |

| I | Intervention | Occupational trauma, course-related stress |

| C | Comparator | No comparator |

| O | Outcome | Prevalence of stress disorders |

Methods

Study design

This review aimed to identify the prevalence of stress disorders in healthcare students, so targeted prevalence studies such as descriptive cross-sectional studies focused on healthcare students for inclusion.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search of two electronic databases (MEDLINE and PubMed) was conducted between February and March 2022 to identify studies assessing the prevalence of stress disorders in healthcare students.

Search term variations included the range of stress disorders and students, with the following terms: (‘stress disorder’ OR ‘Acute Stress Disorder’ OR ‘Post Traumatic Stress Disorder’ OR ‘secondary trauma’ OR ‘secondary traumatic stress’ OR ‘vicarious trauma’ OR ‘compassion fatigue’ OR ‘anxiety’ OR ‘depression’ OR ‘occupational stress’ OR ‘occupational trauma’ OR ‘mental disorder’ AND ‘prevalence’ AND ‘healthcare students’ OR ‘nursing students’ OR ‘student nurses’ OR ‘undergraduate nurses’ OR ‘paramedic students’ OR ‘student paramedics’ OR ‘trainee paramedics’ OR ‘student midwives’ OR ‘midwifery students’). A combination of the search fields ‘title’ and ‘abstract’ were used to ensure the best possible search result. The search covered all studies between 2010 and 2022, in English and with full-text availability.

An advanced Google Scholar search was also conducted to identify recent unpublished studies. This included the same search terms but restricted to title.

Date and language limitations were included to narrow the search and make it more specific.

A sample search was: 1.‘stress disorder’ ti,ab; 2.‘acute stress disorder’ ti,ab; 3.‘post-traumatic stress disorder’ ti,ab; 4.‘secondary trauma’ ti,ab; 5.‘secondary traumatic stress’ ti,ab; 6.‘vicarious trauma’ ti,ab; 7.‘compassion fatigue’ ti,ab; 8.‘anxiety’ ti,ab; 9.‘depression’ ti,ab; 10.‘occupational stress’ ti,ab; 11.‘occupational trauma’ ti,ab; 12.‘mental disorder’ ti,ab; 13.‘1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12’; 14.‘healthcare students’ ti,ab; 15.‘nursing students’ ti,ab; 16.‘student nurses’ ti,ab; 17.‘undergraduate nurses’ ti,ab; 18.‘paramedic students’ ti,ab; 19.‘student paramedics’ ti,ab; 20.‘trainee paramedics’ ti,ab; 21.‘student midwives’ ti,ab; 22.‘midwifery students’ ti,ab; 23.‘14 OR 15 OR 16 OR 17 OR 18 OR 19 OR 20 OR 21 OR 22’; 24.‘Prevalence’ ti,ab; 25.‘13 AND 20 AND 21’.

Inclusion criteria included quantitative observational studies that had: analysed the prevalence of stress disorders; involved nursing, midwifery or paramedic students; considered a range of correlational factors; and used validated tools to assess prevalence.

Studies were excluded if they: involved medical, dentistry, pharmacy or other allied healthcare students; involved qualified health professionals; considered correlational factors related to academic pressures only; were inaccessible so could not be reviewed fully; were interventional or case-control studies; or focused on prevalence since the emergence of COVID-19/any other outbreak/disaster.

Observational studies are effective at measuring prevalence in a specific population, at a specific point in time or over a period of time (Coggon et al, 2009), making them appropriate for this review. The use of validated tools was included to ensure outcome assessment validity (Munn et al, 2015).

The rationale for including and excluding specific groups of students was to include courses that shared some resemblance, such as around academic requirements, course structure and clinical practice exposure. The study was also intended to focus on frontline healthcare students with direct patient contact and potential exposure to traumatic events linked to the development of stress disorders.

Studies focusing on prevalence since COVID-19 or any other disaster were excluded as the aim was to identify prevalence linked to the nature of the course in normal circumstances. All other criteria were determined by the research questions.

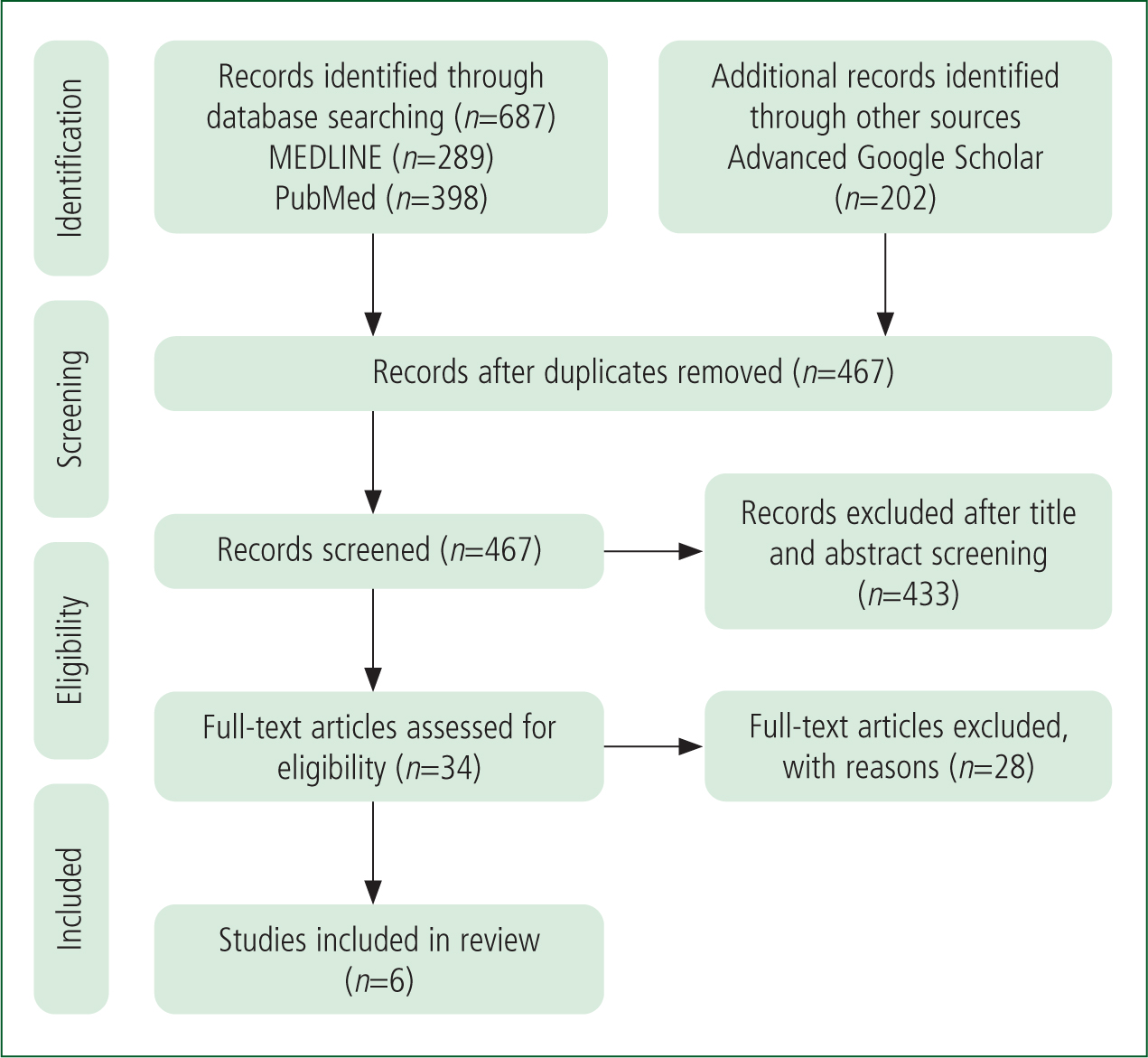

At first search, 889 references were retrieved; 289 from MEDLINE, 398 from PubMed and 202 from Google Scholar. After duplicates were removed, 467 articles were retained. Titles and abstracts were reviewed for all articles, as well as full-text availability for articles retrieved through Google Scholar. Following this, 433 articles were excluded, leaving 34 articles to be assessed for eligibility.

After full texts were reviewed, 28 studies were excluded, leaving six articles for inclusion in the review. Those 28 excluded were for reasons including being focused on: comparisons of qualified staff, or included them; predicting stress disorders; students from disciplines not meeting the inclusion/eligibility criteria; interventions, or included them; primarily contributing factors; one area as a cause of stress disorders, such as studying or clinical practice; or prevalence since COVID-19. In addition, primary research and systematic reviews were excluded. Selection is shown in the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) (Moher et al, 2009).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was completed and documented on a data extraction form developed by the author.

Extracted data included: first author's last name; year of publication; study design; participant information (healthcare course, number and age of participants); geographical location; tools used; stress disorder(s) assessed; prevalence of stress disorder(s) identified; and type of publication. This was done to enable effective data synthesis.

Following data extraction, the final articles were identified and appraised for their methodological quality using the Joanna Briggs Institute prevalence critical appraisal tool (Munn et al, 2015). Although there is no consensus on which domains should be assessed in prevalence studies (Shamliyan et al, 2010), a systematic review of quality assessment tools identified three key domains—population and setting; condition measurement; and statistics—which were based on the main components of a prevalence research question.

This review deemed the Joanna Briggs Institute prevalence critical appraisal tool to be the most appropriate because of its high level of methodological rigour. The tool assesses appropriateness and representativeness of the sample, reliability and validity of condition measurement, appropriate statistical analysis and other factors relevant to appraisal such as participant and setting details (Migliavaca et al, 2020).

Results

All six studies focused on prevalence, five were cross-sectional and one was exploratory, descriptive (Table 2).

| Author (year) | Location | Study design | Population type | Number of participants | Age range | Outcomes measured | Method to assess | Prevalence of outcome (%) | Publication type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chatterjee et al (2014) | India | Analytical, cross-sectional study | Nursing students | 180 |

17–26 years | Depression | BDI |

Total 63.9 |

Journal article |

| De Moura Camargo et al (2014) | Brazil | Exploratory, descriptive study | Nursing students | 91 |

17–40 years | Depression | BDI |

Total 99.8 |

Journal article |

| Xu et al (2014) | China | Cross-sectional study | Nursing students | 763 |

NR | Depression | CES-D |

Total 22.9 | Journal article |

| Chen et al (2015) | Taiwan | Cross-sectional study | Nursing students | 625 |

16–20 years | Depressive symptoms | ADI |

Total 32.6 |

Journal article |

| Zeng et al (2019) | China | Cross-sectional study | Nursing students | 544 |

17–24 years | Depression, anxiety, stress | DASS-21 |

Total |

Journal article |

| Alzahrani et al (2021) | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional study | Paramedic students | 181 |

NR | Anxiety | GAD-7 |

Total 67.4 |

Unpublished, non-peer-reviewed research article |

| Total pooled prevalence % All outcomes 41.4 Depression 49.58 Anxiety 54.55 Stress 20.2 |

ADI: Adolescent Depression Inventory; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; DASS-21: Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale 21; GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder-7 scale; NR: not recorded; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; TC-SINS: Taiwanese-Chinese Stress in Nursing Students Scale

Four studies had depression as an outcome, one included anxiety and one included depression, anxiety and stress.

Five included nursing students, and one included paramedic students.

The results from all studies were merged into descriptive data, correlations, and prevalence of outcomes (Table 2).

Descriptive data

Measurement tools

All studies adopted self-reported questionnaires for measuring outcomes, although the specific tools used varied.

Two used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), a 21-item questionnaire evaluating depression severity. Scores were in a range of 0–63; the higher the score, the greater the severity (Jackson-Koku, 2016). De Moura Camargo et al (2014) adopted the recognised point scale: <10: minimal; 10–18: mild to moderate; 19–29: moderate to severe; and 30–63: severe, while Chatterjee et al (2014) adopted a different approach based on the following scores: 0–9: normal/none; 10–19: mild; 20–29: moderate; 30–39: severe; and ≥40: very severe. Differences between these two approaches are minimal; however, levels of <10 on the BDI have proven significant for some people (Bush et al, 2001) so it may be better to grade this range as minimal rather than normal/none.

Other tools included: the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a four-factor, 20-item scale measuring depressive symptomology (Carleton et al, 2013); the Chinese version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21), a well-established instrument to measure symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress (Beaufort et al, 2017); the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) test, a valid and efficient seven-item scale to assess anxiety (Spitzer et al, 2006); the Adolescent Depression Inventory, a 20-item questionnaire developed by Taiwanese researchers Huang and Hsu (2003) to assess depressive symptoms in adolescents and teenagers (Chen et al, 2015); the Situational Anxiety Scale, adapted from Spielberger's Situational Trait Anxiety Scale by Chung and Long in 1984 (Chen et al, 2015); the Taiwanese-Chinese version of the Stress in Nursing Students Scale (TC-SINS), based on the Stress in Nursing Students Scale developed by Deary et al in 2003; and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), which assesses sleep quality and disturbances (Buysse et al, 1989).

Demographic data

In total, 2384 students were included in this review, 2203 nursing and 181 paramedic students.

All but one study (Chatterjee et al, 2014) included participants' sex, which showed the sample was predominantly female (n=1915). There were 289 men, leaving 180 where sex was not identified.

Women were overrepresented in studies on nursing students, while men were overrepresented in the paper on paramedic students (Alzahrani et al, 2021). This may be because of the nature of the professions, with nursing historically portrayed as a feminine profession (Mao et al, 2021), and paramedicine being a largely male-dominated profession (Sporer, 2016; Health and Care Professions Council, 2017). Additionally, the study about paramedic students was conducted in Saudi Arabia, where some ambulance services are staffed by men only (Alharthy et al, 2018).

Four studies provided data on age (Chatterjee et al, 2014; De Moura Camargo et al, 2014; Chen et al, 2015; Zeng et al, 2019), providing an overall age range of 16-40 years, although only 10 participants were aged above 26 years (De Moura Camargo et al, 2014).

One study included junior college students (Chen et al, 2015), while the rest were undergraduate students in years 1–4.

Geographical locations included Saudi Arabia (Alzahrani et al, 2021), India (Chatterjee et al, 2014), Brazil (De Moura Camargo et al, 2014), Taiwan (Chen et al, 2015), and China (Xu et al, 2014; Zeng et al, 2019).

Correlations

Four studies analysed correlations between outcomes and variables (Chatterjee et al, 2014; Xu et al, 2014; Chen et al, 2015; Zeng et al, 2019), which have been merged into four categories: academic; demographic; psychosocial; and health. A summary of correlations is shown in Table 3.

| Study | Academic |

Demographic |

Psychosocial |

Health |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chatterjee et al. (2014) | A lack of interest in course: P Insecurity over future placement: P | Living facilities: I | Familial disharmony: P |

Perceived health problems: I |

| De Moura Camargo et al (2014) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Xu et al (2014) | Better academic performance: N |

Sex: I |

Better interpersonal relationships: N |

Higher frequency of exercise: N |

| Chen et al (2015) | Low grade point average: P |

NR | NR | Overeating as stress strategy: P |

| Zeng et al (2019) | Not completed 8–12 months of clinical practice: P | NR | Not participating in regular leisure activities: P |

Being physically inactive: P |

| Alzahrani et al. (2021) | NR | Female sex | NR | NR |

NR: not recorded

In the academic category, positive correlations included a lack of interest in the course or clinical placement, poor academic performance, academic stress and concerns about future careers (Chatterjee et al, 2014; Xu et al, 2014; Chen et al, 2015). In one study (Xu et al, 2014), fathers' education level had a positive correlation, while the mothers' education level was found to have no effect.

Demographic factors such as living conditions during and before starting the course and being an only child did not correlate with any outcomes (Chatterjee et al, 2014; Xu et al, 2014). Xu et al (2014) also found participant sex had no effect on depression, while Alzahrani et al (2021) found women had a higher prevalence of anxiety.

In the psychosocial area, Xu et al (2014) and Chatterjee et al (2014) found positive correlations between problems in relationships with family and peers and in love affairs; however, Chatterjee et al (2014) found there to be no effect if detached from family members, which is slightly contradictory as it can be argued that family detachment is an example of a problem in a family relationship.

Zeng et al (2019) found positive correlations between all outcomes and: the presence of negative life events; a lack of participation in leisure activities; and more than 4 hours' daily screen time. They also found a lack of religion increased anxiety, while financial problems increased depression. This in contrast to Chatterjee et al (2014), who found financial constraints had no effect on depression.

Being physically inactive with a poorly perceived health status was found to correlate with increased levels of negative outcomes in two studies (Xu et al, 2014; Zeng et al, 2019). This supported a negative correlation in students who had higher perceptions and use of support services (Xu et al, 2014). These findings contradict those found by Chatterjee et al (2014) however, who found no effect from perceived health problems.

This was also the case with personal habits, where Chatterjee et al (2014) found no effect, while others found positive correlations with sleep problems and overeating as a strategy to cope with stress (Chen et al, 2015; Zeng et al, 2019). It must be noted, however, that Chatterjee et al (2014) did not provide any details regarding what constituted personal habits.

Chen et al (2015) reported stress and anxiety were associated with depressive symptoms, supporting the correlation between all three outcomes (Zeng et al, 2019).

Prevalence of outcomes

All studies found a high prevalence of outcomes, with overall scores of: 63.9%, 32.6%, 99.8%, 22.9% and 28.7% for depression; 67.4% and 41.7% for anxiety; and 20.2% for stress. Pooled prevalence of depression was 49.58%, anxiety 54.55% and stress 20.2%.

Most students fell within the lower ranges of minimal, mild or mild to moderate for all outcomes but some were in the higher ranges. Although age ranges and year groups were provided, only two studies identified differences in prevalence within these parameters.

Alzahrani et al (2021) found women had a higher prevalence of anxiety, with 77.1% having some degree of anxiety, and 33.3% having moderate-to-severe level, while 63.9% of men had some degree of anxiety, with 21.1% experiencing moderate to severe levels. Between year groups, they reported third-year students had a higher prevalence than those in their fourth year, with 73.1% of third years and 62.7% of fourth years reporting some level of anxiety, while 32.9% of third and 17.2% of fourth years reported moderate to severe amounts.

This decline across the year groups was also reported by Chatterjee et al (2014), who found a decline in prevalence of moderate and severe depression between years 1 and 4. Mild depression was found to be highest in year 4, however.

Discussion

With evidence suggesting the presence of stress disorders in healthcare students, this review aimed to identify the prevalence in a specific population of healthcare students. This included nursing, paramedic and midwifery students; however, because of a lack of studies in two populations, the review was quite limited. Of the six studies, five included nursing students, one included paramedic students and none included midwifery students, resulting in 2384, 181 and 0 students respectively.

This difference reflects the global population of healthcare professions, with nursing and midwifery making up 50% of the workforce. This includes a population of approximately 25 million nurses compared to 1.9 million midwives (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2022) and fewer than one million paramedics (Williams et al, 2021).

The proportions of each sex also reflected the global population in healthcare, with 80% of participants being women and 70% of the global workforce being female (WHO, 2022). Coincidentally, the WHO (2021) reported a higher prevalence of depression in women, which supports the high prevalence of depression found in this review, given that most participants were female, and in other studies (Essau et al, 2010; Young et al, 2010; Ghodasara et al, 2011; Ibrahim et al, 2013; Albert, 2015). Although most of these studies were not directly comparing the sexes, they still found a higher prevalence in women. This review did not specifically compare the sexes because they were both represented disproportionately, so comparison studies are required.

A range of stress disorders in healthcare students, including PTSD, secondary traumatic stress and depression have been reported in research (Fjeldheim et al, 2014; Wild et al, 2020; Ogińska-Bulik et al, 2021), yet this review examined only the prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress, with depression as a priority. This is not surprising, given that depression is one of the most common mental health disorders, affecting an estimated 280 million individuals worldwide, equivalent to 3.8% of the population (WHO, 2021).

Causes of depression are varied but include some of the influencing factors identified in this review, including relationship issues, poor physical health and stress (Dobson and Dozois, 2008; WHO, 2021). It can also be caused by adverse life events or exposure to trauma (WHO, 2021), which supports previous research (Fjeldheim et al, 2014; Lowery and Stokes, 2005; Bayri Bingol et al, 2020; Ng et al, 2020), but was not identified in this review.

The variables identified in the studies in this review focused on personal circumstances, health and academic factors, which, although they can affect or be affected by the students' course, they are not linked to clinical practice nor exposure to traumatic events. Zeng et al (2019) included life events as a variable, but there were no details about which life events, or whether they were related to their course. The inclusion of additional tools to assess students' exposure to trauma could have provided this information.

There was no significant difference between geographical locations, although it should be noted most studies were in Asia, where education is valued and students are expected to excel academically (Tan and Yates, 2011).

Pressure from parents or themselves may lead to stress if academic expectations are not met, in line with two studies that identified that weak academic achievement and grades were correlated with depression (Xu et al, 2014; Chen et al, 2015).

Western culture does not have the same academic expectations (Tan and Yates, 2011) yet the prevalence of depression found in Brazil was comparable. Tan and Yates' (2011) study did report high levels of overall prevalence but was the only study to include minimal depression rates. Correlations have been made between depression and a lack of interest in the course, which Chatterjee et al (2014) attributed to students feeling compelled to study nursing because of family pressures rather than choosing to do so. This is supported by Poreddi et al (2012), who found only 34.1% of nursing students had enrolled through choice, while the rest signed up for reasons such as parent or family expectations. Zeng et al (2019) also found only one-third of students studied nursing through personal choice, although they did not associate this with the prevalence of any outcomes.

From a methodological viewpoint, all but one study was cross-sectional, which, while an appropriate method to measure prevalence, assesses exposure only at a particular point in time, so cannot determine cause and effect (Song and Chung, 2010).

Regarding stress disorders and correlational factors identified, it was not possible to determine which was present first as either could have influenced the other. For example, people with depression may not want to participate in physical activity, while being physically inactive can lead to depression (Elfrey and Ziegelstein, 2009).

There are also relationships between depression and physical health, with one leading to the other and vice versa (WHO, 2021), supporting correlations found in this review but, again, not establishing cause and effect. Based on this, it was impossible to determine a clear link between the prevalence of stress disorders and the course studied, so further research using cohort or case-control designs may be more effective.

Limitations

This review has several limitations.

First, because of the lack of studies including paramedic and midwifery students, it did not determine the prevalence of stress disorders in those populations. Although one study focused on paramedic students, its quality was questionable as data were limited and it had not been peer reviewed or published. A broader use of search terms to include associated roles such as emergency medical technicians may have yielded more results and identified further studies for inclusion.

Second, the one study focused on paramedic students included the largest number of male participants, which was another limitation. As women were overrepresented in most studies, it was not possible to compare the sexes or generalise to male students.

Third, there was a limited range of stress disorders, and limited variables to identify whether exposure to trauma would influence outcomes.

Fourth, the tools used to measure outcomes were screening tools, which identify symptoms but do not confirm diagnoses. They also measure symptoms at the point of completion, although these could vary depending on the setting and participants' moods (Askim and Knardahl, 2021).

Next, although the design of most studies did identify the prevalence of stress disorders, they did not determine cause and effect. Additionally, the limited range of variables did not establish clear factors that influence the prevalence of stress disorders.

Finally, the review was conducted by a sole researcher, which limited the depth and breadth of search capacity.

Conclusion

This review identified a high prevalence of some stress disorders in some frontline healthcare students. Many of the contributing factors are dynamic and therefore the level of symptoms could vary over time and when circumstances change.

Additionally, most factors are related to personal circumstances and academic expectations rather than the course or exposure to trauma.

Regardless of contributory factors, the high prevalence indicates the need to implement or improve interventions to reduce prevalence.