Primary postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is the most common form of obstetric haemorrhage (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG, 2009). The causes of PPH are referred to as the ‘four T's’ (RCOG, 2009): Tone (abnormalities of uterine contraction), Tissue (retained products of conception), Trauma of the genital tract, and Thrombin (abnormalities of coagulation). Failure of the uterus to contract after the second stage of labour (atonicity) is the most common cause of PPH (Matthews et al, 2007). RCOG (2009) state ‘the majority of maternal deaths due to haemorrhage must be considered preventable’, based on evidence from the report WhyMothersDie (Confdential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH), 2004). Founded over 50 years ago, CEMACH aims to reduce the instances of maternal death in the (UK. Confdential enquiries into maternal deaths and the triennial publication of key fndings and recommendations by CEMACH enable clinicians and NHS Trusts to improve maternity practice (Lewis, 2007). Although maternal death is increasingly rare in the UK, research suggests that mortality directly related to pregnancy has increased in recent years (Lewis, 2007). Therefore it is important that paramedics are adequately trained in the effective treatment and prevention of PPH.

This article refers to the occurrence of PPH during the third stage of labour, within the pre-hospital setting, when a midwife is not present at scene. The third stage of labour is defned as ‘the time from the birth of the baby until the expulsion of the placenta and membranes' (NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence), 2007).

Defning blood loss

The World Health Organization (WHO) defnes postpartum haemorrhage as ‘a [blood] loss of 500 ml or more from the genital tract after delivery’ (WHO, 2008). However, the RCOG (2009) suggests most patients in the UK can physiologically cope with this and recommends a one thousand millilitre limit to prompt treatment. Postpartum haemorrhage is further defned as primary (occurring within 24 hours of delivery) or secondary (twenty four hours after delivery of the baby and six weeks postpartum) (WHO, 2008).

Increase in home births

Although the rate of home births in England and Wales is reported to have decreased, 2.5 % of women chose to give birth at home during 2010 (Offce for National Statistics (ONS), 2011b), equating to over eighteen thousand births (ONS, 2011a). In the case of a planned home birth, the patient should be supported by a qualifed midwife. In the case of a complicated birth, paramedics may be called by the midwife for assistance and transfer to an obstetric unit (RCOG and Royal College of Midwives (RCM), 2007). In the case of an unexpected birth, paramedics may be called to assist with the birth in the absence of a midwife.

Availability of choice

A survey by the Department of Health (DH, 2005) found that more mothers would have liked a greater choice about the types of maternity care offered to them and places to give birth. Government policy has since advocated ‘four national choice guarantees’, including the choice of having a home birth supported by a midwife (DH, 2007). The increasing accessibility of home births may result in an increasing number of future mothers considering the home birth setting. A national shortage of midwives has also prompted recommendations to increase home births (RCM, 2011), as they are believed to reduce interventions and midwives' time. A study about birth settings in England during 2008–2010 found that interventions during labour and birth are less common in births planned in non-obstetric unit settings, while adverse perinatal outcomes are uncommon in every birth setting (Birthplace in England Collaborative Group, 2011).

Rising fertility rates

Fertility rates have risen since 2001, especially amongst women aged 30–39 (ONS, 2011a), while women aged between 30–39 years are more likely to choose home births (Birthplace in England Collaborative Group, 2011; ONS, 2011b).

Home births are dependent on adequate support and transfer pathways from ambulance services (RCOG and RCM, 2007). The Birthplace in England Collaborative Group (2011) found 45 % of healthy, low-risk women, who were having their frst baby and planned to give birth in a non-obstetric unit location, were transferred to an obstetric unit during labour or immediately after birth. This statistic reduced with subsequent births, as only 12 % of women who had given birth two or more times previously were transferred to an obstetric unit before or after a planned home birth (Birthplace in England Collaborative Group, 2011). The study included 97 % of NHS Trusts in England providing home birth services between 2008–2010.

Consequently, paramedics are likely to fnd themselves increasingly exposed to obstetric cases in the pre-hospital setting, underlining the need for further education in this feld of healthcare.

Increase in mortality

Research states an increase in the number of maternal deaths resulting from haemorrhage between the years 2000–2002 (CEMACH, 2004), where nine out of fourteen women per 100 000 died as a result of PPH from 2003–2005 (Lewis, 2007). The second study was conducted over a short timescale of two years, so the ability to generalise from this data is questionable, although a similar trend in the number of deaths between this study and the previous study is identifed (Lewis, 2007). ‘Less than optimal care’ accounted for the deaths of ten of the women during 2003– 2005 (Lewis, 2007). This stresses the importance of early recognition of signs and symptoms and effective management of obstetric emergencies by midwives and paramedics alike. This is especially the case in the pre-hospital setting, where there are far fewer resources for the clinician to call upon for assistance (Wollard et al, 2008).

Education of paramedics

In order to examine the current standards of obstetric practice within UK paramedic practice, it is necessary to consider the education of paramedics about this topic. Historically, the education of paramedics surrounding the management of obstetric emergencies has been poor, as paramedic training largely focused on resuscitation and trauma management (DH, 2005) and failed to include detailed assessment skills and underlying pathophysiology of conditions. Research suggests that obstetric emergencies did not feature as part of the UK paramedic curriculum before 1999 (Wollard et al, 2008), yet after it was introduced, only a basic thirteen-stage checklist was included for the management of PPH (Ambulance Service Association (ASA), 2003b). The defnition of PPH was inconsistent between ambulance technician (ASA, 2003a) and paramedic (ASA, 2003b) training programmes, resulting in confusion between clinicians about how much blood loss constituted PPH. Training failed to address the difference between active and physiological management of the third stage of labour and how this may affect the likelihood of the patient developing PPH.

Although in recent years there has been a focus on moving paramedic training away from objective-based courses to evidence-based practice delivered by higher education institutions (DH, 2005), this fails to address the education needs for the majority of the UK paramedic workforce who have completed the Institute of Health and Care Development (IHCD) Paramedic training programme (DH, 2007). In addition to this, paramedics qualifying prior to 1999 may not have received the obstetrics update (Wollard et al, 2008).

Progression towards higher education

From the transition to evidence-based practice, it is arguable that future pre-registration student paramedics will receive more detailed training about the treatment of obstetric emergencies. The number of pre-registration paramedics taught by midwives, as opposed to nursing or paramedic lectureres, is still unknown (Wollard et al, 2008). It is possible that pre-registration students may not gain clinical experience treating PPH, due to the sporadic nature of ambulance work. Students at one UK university are prepared to manage PPH via education about the evidence-based management of normal labour and obstetric emergencies by practicing midwives. A four-day obstetric programme provides opportunities for students to explore underlying pathophysiology, gain an increased understanding of the midwife's role in childbirth and practice clinical skills under simulation, including bimanual compression, a skill not featured in the IHCD programme (ASA, 2003b) or the UK Ambulance Service Clinical Practice Guidelines (Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC), 2006). The opportunity to speak to midwives about their experiences of managing obstetric emergencies may prove invaluable, and a luxury that may not have formed part of traditional paramedic training programmes (Wollard et al, 2008).

Length of pre-registration training

While the transition towards higher education training demonstrates a positive move towards ambulance services adopting evidence-based practice, pre-registration student paramedics are delayed entering the workforce due to the increased length of paramedic training, which typically last three years (London Ambulance Service NHS Trust, 2011).

The move away from IHCD training programmes to higher education is an ongoing process of change and it will be several years until all UK paramedic training is at Bachelor of Science (Honours) level. The College of Paramedics (2012) recently conducted a survey of members to establish the minimum threshold for academic entry to the profession. Government recommendations were issued in 2005 for the ‘revised education and training of ambulance clinicians' (DH, 2005): it has taken four years for many ambulance trusts to cease using the IHCD Paramedic programme (Health Professions Council (HPC), 2011a), while other trusts will remain teaching the IHCD paramedic course until 2012 (HPC, 2011b). Students studying IHCD courses may not beneft from the latest evidence-based practice, considering the training materials for IHCD courses were published nine years ago (ASA, 2003b). It is necessary to address the clinical practice of existing paramedics, and the most effective method of achieving this would be to update the obstetric clinical practice guidelines in conjunction with additional training, such as the Pre-hospital Obstetric Emergency Training (POET) course.

Active versus physiological management: third stage of labour

The third stage of labour may be either actively or physiologically managed (Table 1) and all midwives are competent in both methods (RCM, 2008). Considering that active management is recommended in midwifery practice (NICE, 2007) and therefore likely to be adopted by an attending midwife, why are paramedics not trained in active management, in order to competently assist the midwife? Currently, only physiological management is practiced by paramedics, defned as ‘no routine use of uterotonic drugs, no clamping of the cord until pulsation has ceased [and] delivery of the placenta by maternal effort’ (NICE, 2007). Existing ambulance service clinical guidelines are based upon the physiological management of the third stage of labour (JRCALC, 2006) although this is not explicitly stated. The guidelines were due to be updated in April 2011 (The University of Warwick, 2009) and are due for publication in 2012.

Providing patient choice

Current midwifery practice guidelines advise ‘women at low risk of postpartum haemorrhage who request physiological management of the third stage should be supported in their choice' (NICE, 2007; RCM, 2008), although a study conducted for the DH found that 47 % of women did not feel well-informed about what to expect when giving birth (Taylor Nelson Sofres, 2005). Therefore, it is questionable whether enough women are given the information necessary prior to birth in order to make informed decisions about their treatment and care during labour. At present, paramedics do not provide patient choice over active or physiological management (JRCALC, 2006). NICE (2007) state that clinical intervention should be kept to a minimum and not advised during normal labour (a physiological approach), but this guidance is contradicted by a conficting statement: ‘active management of the third stage is recommended’ (NICE, 2007).

Reducing the risk of PPH

In order to reduce the risk of PPH (Table 2) in labour managed by paramedics in the absence of a midwife, active management of the third stage of labour should be adopted by NHS Ambulance Trusts. Active management is defned as ‘routine [prophylactic] use of uterotonic drugs, early clamping and cutting of the cord [and] controlled cord traction’ (NICE, 2007). Reed et al (2010) suggest ‘all is required of the paramedic is to ensure blood loss remains within normal limits' during the third stage of labour. However, this does not account for instances of haemorrhage and provides no guidance for treating PPH in a low-resource setting. Yet there is overwhelming evidence to suggest that active management of labour is more benefcial to the patient, reducing the chance of moderate and severe PPH (Fry, 2007; NICE, 2007) by approximately 60 % (RCOG, 2009). However, it is also important to note that active management often results in adverse side-effects if certain uterotonic drugs (oxytocin or ergometrine) are administered during the process (Begley et al, 2011), making it a seemingly less favourable choice in the eyes of the patient. In the case of an undiagnosed second twin in utero, active management could result in the death of the second twin, although cases are extremely rare (Loughney et al, 2006). This underlines the importance of accurate history-taking prior to carrying out any clinical intervention.

Prophylactic administration of uterotonic drugs

Syntometrine is the trade name for ‘oxytocin-ergometrine maleate’, a combination drug which induces uterine contraction (Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), 2012). Syntometrine is already included within ambulance service clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of haemorrhage ‘where bleeding is uncontrollable by uterine massage’ (JRCALC, 2006). At present, the drug is not indicated for routine prophylactic administration during the third stage of labour, but if the clinical guidelines adopted active management of the third stage of labour, syntometrine could be administered routinely by paramedics for the prevention of PPH (NICE, 2007).

It is important to note that not all ambulances contain a refrigerated compartment for storage of syntometrine. As a consequence of keeping the drug in warm temperatures, stock must be discarded due to the instability and short shelf-life (Matthews et al, 2007). This may lead to shortages of drug stock. In addition, administration of syntometrine is contra-indicated in patients suffering pre-eclampsia or hypertension (JRCALC, 2006; RPS, 2012).

Oxytocin may also be administered on its own, rather than combined with ergometrine, and is more commonly referred to by the trade name ‘syntocinon’ (RPS, 2012). Syntocinon has a lower risk of side-effects, in particular vomiting, than syntometrine, and is the uterotonic drug of choice for women with a low risk of PPH (RCOG, 2009). Unlike syntometrine, syntocinon may also be administered to patients suffering from pre-eclampsia (RPS 2012), which raises the question of why syntocinon is not licensed for administration by paramedics? However, syntometrine is proven to be more effective than other uterotonic drugs in reducing the risks of PPH between fve hundred and one thousand millilitres (Rogers et al, 2011) which may account for its usage within pre-hospital healthcare.

Other ambulance clinicians

Under the Prescription Only Medicines (Human Use) Order 1997, non-paramedic clinicians such as Ambulance Technicians, Emergency Care Assistants and Emergency Care Support Workers may administer certain drugs to preserve life. However, syntometrine is only licensed for paramedic administration (Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, 2005). Considering the life-threatening nature of PPH (WHO, 2008) and non-paramedic clinicians representing a signifcant proportion of clinical staff within many NHS Ambulance Trusts (NAO, 2011), perhaps all clinicians should be allowed to administer a prophylactic uterotonic drug, when all other methods of haemorrhage control have failed? In addition, paramedics could also adopt other methods of controlling PPH, such as bimanual compression and administering tranexamic acid, currently not included in clinical practice guidelines. At present, paramedics who are unable to administer syntometrine will fnd themselves in a helpless position, should uterine massage be unsuccessful in controlling haemorrhage.

Reducing the risk of PPH during physiological management

Skin-to-skin contact

Immediately after delivery, the baby should be dried and placed skin to skin with the mother (NICE, 2007), in order to stimulate the mother's natural production of oxytocin. This promotes uterine contraction and separation of the placenta. In addition, early breast feeding or nipple stimulation stimulates oxytocin production, reducing the risks of uterine atonicity and PPH (Loughney et al, 2006).

Environmental factors

A calm and stress-free environment is also important during the delivery. Keeping the environment calm and reducing stress helps to ensure that the woman's physiology remains at its optimum function (Fahy et al, 2010), which subsequently reduces the likelihood of uterine atonicity and PPH. However, this may be diffcult in the case of an unplanned home birth, which is likely to be stressful for the woman. Therefore, it is important that ambulance crews remember to provide reassurance at all times to the woman and the woman's birthing partner, if present.

Treatment and management of PPH

Ambulance service clinical practice guidelines (JRCALC, 2006) state that where possible, PPH should be treated by paramedics en route to hospital. However, crews called to sudden or unplanned births will not have advance warning to plan the progression of care and could be faced with a patient suffering PPH on arrival (Loughney et al, 2006). Such patients require stabilisation prior to movement, wherever possible (JRCALC, 2006). In any case of blood loss, it is important to recognise the physiological symptoms of hypovolaemic shock, such as tachycardia, hypotension and pallor, although these are late signs of fuid depletion (Porter, 2007). Current ambulance service clinical guidelines advise treatment using uterine massage, administration of syntometrine, fuid replacement where the patient is haemodynamically compromised and immediate transportation to the nearest obstetric unit (JRCALC, 2006).

Privacy and dignity

The use of manual methods, such as uterine massage and direct pressure to the vaginal entrance when necessary (JRCALC, 2006) could prove problematic for male paramedics, as the nature of such procedures offer little privacy or dignity to the patient. Consent is required before treatment of the conscious patient may commence (JRCALC, 2006) but patients may be unwilling to provide informed consent for a male practitioner to perform such intimate procedures.

Uterine massage

Atonic haemorrhage (bleeding from the placental site due to a lack of tone in the uterus) is the most common cause of PPH (Matthews et al, 2007). Therefore, uterine massage (rubbing up a contraction) is the frst line of treatment for PPH, as recommended in current clinical guidelines (JRCALC, 2006). Uterine massage is performed by palpation of the abdomen in order to locate the top of the uterus (the fundus), which is usually found at the level of the umbilicus. The practitioner massages the fundus with a cupped hand in a circular motion to stimulate uterine contraction (JRCALC, 2006).

In order for uterine massage to be effective, it is necessary for the woman to empty her bladder (WHO, 2008; RCOG, 2009). This is not stated in the IHCD paramedic curriculum or clinical practice guidelines, so it is unlikely to be acknowledged by all paramedics at present. This will reduce the effectiveness of uterine massage performed by paramedics, consequentially increasing the risk of uncontrolled haemorrhage. In midwifery practice, the midwife will empty the woman's bladder by inserting a urinary catheter (RCOG, 2009). However, at present, catheterisation is not included in the UK paramedic scope of practice (JRCALC, 2006).

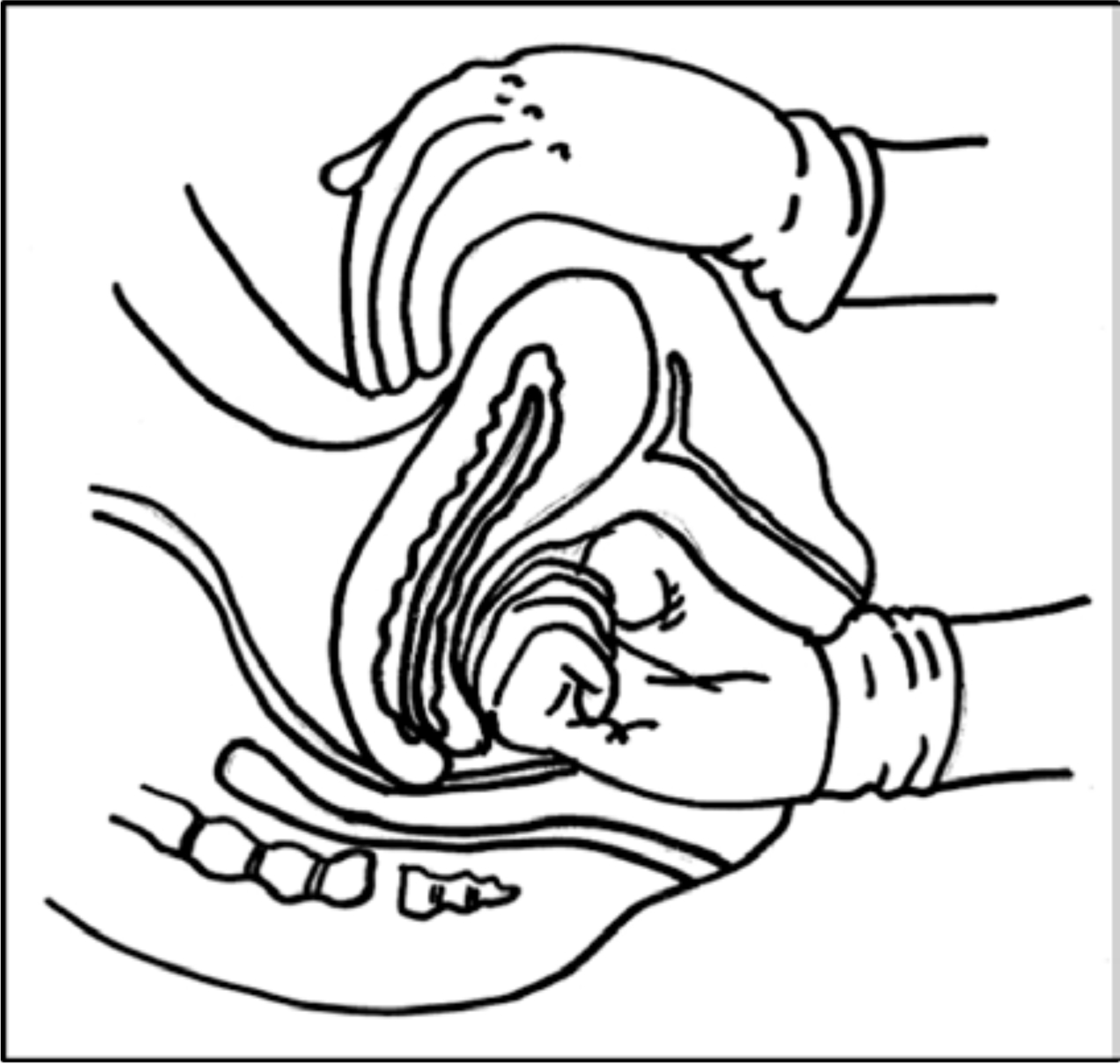

Bimanual compression of the uterus

In cases where syntometrine is ineffective or unavailable and external uterine massage is ineffective, internal bimanual compression of the uterus (Figure 1) is indicated (WHO, 2008; RCOG, 2009). Bimanual compression should not be performed when the placenta is retained in the uterus. This procedure is performed by inserting a gloved hand into the vagina and forming a frst, while applying pressure against the anterior wall of the uterus. Maintaining this position, the other hand is placed on top of the abdomen behind the fundus and applies pressure against the posterior wall of the uterus (WHO, 2008) until the haemorrhage is controlled.

For pre-hospital cases, this is a last-resort method to address uncontrollable haemorrhage, but in hospital it is considered a frst-line treatment method (RCOG, 2009), which questions why ambulance clinical guidelines do not acknowledge this practice. Bimanual compression is more effective than external uterine massage (WHO, 2008), however, the practicality of performing this procedure in the pre-hospital setting is questionable, due to pain, being in a moving vehicle and the likelihood of analgesia such as morphine being contra-indicated due to hypotension and time constraints (JRCALC, 2006). Increased risk of infection via ‘direct transfer through the hands of clinical practitioners' (DH, 2008) may account for this practice being excluded from guidelines, especially within a non-aseptic environment.

Tranexamic acid

Although syntometrine is the drug of choice for treatment of PPH, considering the contraindications (JRCALC, 2006), it would be benefcial for paramedics to carry an alternative drug for administration when syntometrine is ineffective or contraindicated. Tranexamic acid (TXA), which reduces excessive or recurrent bleeding (Shakur et al, 2010), is already used in hospital for control of persistent postpartum haemorrhage (Dunn and Goa, 1999) and currently under trial by one UK ambulance service (BBC, 2011). A clinical trial is also currently in progress to determine the effects of TXA on women with clinically diagnosed postpartum haemorrhage (Shakur et al, 2010). This area of practice is currently under development and may lead to changes in the paramedic's management of PPH in future.

Conclusion

Increasing fertility rates and greater patient choice could suggest that the number of home births is likely to rise in future years, potentially providing more frequent maternity cases for paramedics. Active management of the third stage of labour reduces the likelihood of PPH and should be adopted by UK NHS ambulance trusts. PPH could be managed more effectively by paramedics and other ambulance clinicians if a wider scope of practice was introduced. It is necessary for clinicians to undertake further training before bimanual compression and administration of tranexamic acid may be introduced to clinical practice. Meanwhile, paramedics can reduce the risks of PPH occurring during a physiological third stage of labour by ensuring a calm and relaxed birthing environment and encouraging skin-to-skin contact and early breastfeeding after the baby is born.

The Health Professions Council (HPC, 2007) standards for paramedics state a requirement to ‘engage in evidence-based practice’ and ‘evaluate practice systematically’ (HPC, 2007). Paramedics and NHS ambulance trusts should be prompted to consider current obstetric and maternity practice and invest in further education, so that we may provide the highest possible standard of care to future mothers.