Balancing expanding scopes of practice with safe, effective patient care in modern prehospital landscapes can prove challenging (Barody, 2016; Dodd, 2017). In the UK ambulance service, increasing public demand, changing user needs and a growing evidence base has driven the rapid evolution of frontline roles (Harrison, 2019; Newton et al, 2020). In addition, a patient-centred focus has led to more stringent care quality regulation (Santana et al, 2019).

The ambulance quality indicators (AQIs) were implemented in April 2011 to drive service improvement through a framework of system and clinical outcome measures (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2020). NHS ambulance trusts submit monthly data providing insight into patient safety and success, including ambulance response times and a limited number of clinical outcomes, such as cardiac arrest and stroke (Table 1) (NHS England, 2019a).

| Ambulance system indicators | Clinical outcome indicators |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Source: NHS England, 2019a; 2019b

In a review predating the AQIs, the NHS recognised that staff health and wellbeing are intrinsically linked with patient care outcomes; impaired staff fitness can render care unsafe and ineffective (Boorman, 2009). This was one driver of the NHS Commissioning for Quality and Innovation scheme developed in 2017, which incentivises trusts to improve staff wellbeing through compliance with three indicators (Table 2); NHS England, 2018). However, it is claimed the ambulance service is in crisis—overstretched, underfunded and experiencing unusually high rates of turnover, sickness, and poor work-related wellbeing in its staff (Wankhade, 2018).

| Indicator | Element |

|---|---|

| Improve health and wellbeing of NHS staff | Ensure board engagement and accountability; improve support services and leadership progression; include staff in decision-making processes by recruiting health and wellbeing champions; use diagnostic tools and stress audits to identify areas, individuals and causal factors requiring improvement and help; use evidence-based data to inform interventions; improve prevention strategies; faster treatment and therapy access; increase strategy awareness |

| Healthy food for NHS staff, visitors and patients | Reduce sales of and ban promotions, advertisements and checkout displays of food and drink high in sugar, fat and salt; ensure healthy options are available at all times, including during the night for staff on shift |

| Improve the uptake of flu vaccinations for frontline staff within providers | To build immunity, protect staff and prevent spread |

Source: NHS England (2018)

This suggests current quality assurance and wellbeing measures are not working and that patient care is being compromised by human factors the AQIs do not account for. It also implies ambulance staff are becoming patients, despite the first rule of emergency medical response: protect the responder first (i.e. the ‘danger’ in DR ABCDE) (AACE, 2019a).

To understand if this is the case, evidence will be critically analysed in this study to identify current concern for NHS ambulance service staff wellbeing, using retention, sickness absence and mental welfare as gauges. Underlying causation of such high rates and the impact on patient care quality will also be evaluated, alongside recommendations to improve staff wellbeing and care quality.

The aim is to answer the study questions: is staff wellbeing and its impact on patient care of such a concern that indicators should be included in the AQI framework, and should staff wellbeing be prioritised in its own right, not just because of its impact on patient care? To best consider these questions, any relationship between the AQIs and staff wellbeing will be evaluated.

Methods

This systematised review uses a qualitative synthesis and thematic analysis to account for heterogeneity between articles, with thematic coding to identify mental health trends.

A PCO (population, context and outcome) search protocol was used (Pollock and Berge, 2018). Population terms were varied to include as many frontline roles as possible, including both emergency operations centre (EOC) and clinical personnel.

The wellbeing gauges and subsequent context terms were selected after a preliminary search of the literature identified them as important factors in understanding ambulance staff wellbeing. A basic search was also carried out to identify literature addressing the relationship between staff wellbeing and the AQIs (see Appendix A, available online).

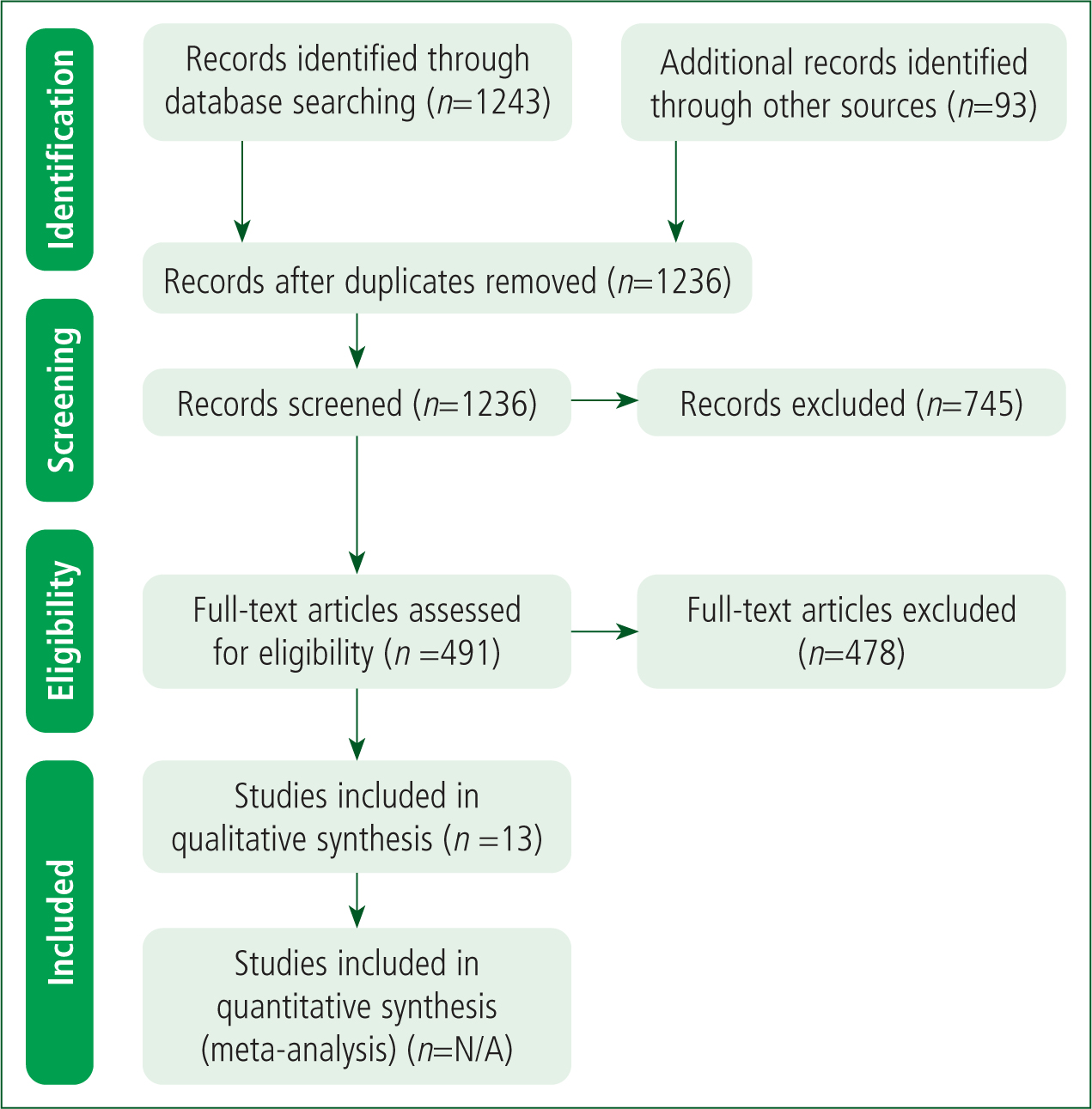

Results were screened using the PRISMA (2009) flow diagram, and the CASP (2018) qualitative and cohort study review checklists were used for consistent data extraction. Included articles comprise original peer-reviewed studies published since the AQI's 2011 inception and pertaining solely to the UK's NHS ambulance service. The majority were identified from only two journals, which is a result of a limited primary evidence base and not selectivity bias. A record was kept of all returns except for websites.

The complete Web of Science collection was searched as it contains most of the journals pertinent to prehospital and emergency healthcare, such as the Emergency Medicine Journal, the Journal of Emergency Medical Services and Prehospital Emergency Care. The British Paramedic Journal (BPJ) and Journal of Paramedic Practice databases were additionally included as they are pivotal to the UK ambulance profession but not part of the Web of Science database. Because of its relatively small size, the BPJ was searched in its entirety. A hand search retrieved additional peer-reviewed and grey literature.

Results

Literature search

A total of 1143 unique articles were screened by title and abstract, and an additional 93 records were identified by hand search. Of 491 eligible returns, 478 were excluded after full assessment. This left 13 peer-reviewed articles for inclusion (Figure 1), which had been published between 2013 and April 2020, the latter date being when the search was conducted. They were collected from all three search contexts: retention: n=2; sickness absence: n=4; and wellbeing: n=4; there was some overlap. Additional articles were identified in the BPJ (n=2) and by the hand search (n=1).

Literature analysis

The literature includes both qualitative (n=10) and quantitative (n=3) articles studying the UK's NHS ambulance population. An overview of the studies is given in Table 3.

| Author | Aims | Sample | Design | Author limitations | Additional limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clompus and Albarran (2016) | How paramedics ‘survive’ their work within the current healthcare climate | Ambulance staff (n=7); female (n=5); male (n=2); white British (n=7) | Free association narrative interviewing; semi-structured, open-ended biographical | Small sample size; gender composition; non-ethnic minority representation; self-selecting sample bias; lack of generalisability; counselling-research barriers blurred | Recruitment strategy did not limit bias; researcher role, bias and relationships not examined |

| Coxon et al (2016) | Explore experiences of EOC staff; identify key stressors, wellbeing impact and improvement measures | EOC dispatchers (n=9); female (n=4); male (n=5) | Interviews; open-ended questions with prompts | Subjective analysis by one researcher; lack of generalisability | Sample selection guided by subjective opinion of EOC manager; unclear if adequate sample size; researcher influence not examined despite potential trust affiliation |

| Drury et al (2013) | Produce an evidence base for ambulance staff psychosocial education needs | LAS, NWAS, HEMS, MERIT and HART operational and management staff; LAS (n=90); NWAS (n=12); female (n=34); male (n=67); no response (gender) (n=1) | Focus groups and Delphi study | None stated | Self-selecting sample bias; unclear if focus group sample to identify Delphi questions were the same used in the Delphi study; researcher influence not examined; findings not critically analysed |

| Gallagher et al (2016) | Obtain views of paramedics in practice on professionalism to produce an evidence base | Ambulance staff (n=16); clinical managers (n=4); specialist paramedics (n=4); paramedics (n=4); student paramedics (n=4) | Delphi study and interviews | Only one university and ambulance trust used, reducing generalisability; lack of practice observation confirming interview findings; lack of patient and family experiences | Recruitment process and sample demographics not explained; researcher bias and relationships not examined; findings and discussion not completely synced |

| Gallagher et al (2018) | Understand disproportionate paramedic HCPC referrals and preventative action | Paramedic, social work and regulation experts (n=14) | Delphi study | Small sample size; significant number of ‘no opinion’ consensus statements; not all participants felt they had relevant expertise | International sample; recruitment unjustified; findings not always clear as part of an article series; HCPC funding conflict of interest |

| Granter et al (2019) | Explore ambulance service work intensity, describing interrelated dimension | Ambulance staff (n=80); senior managers and directors (n=26), managers (n=31), paramedics (n=12), EOC staff (n=11); observations (n=150 h) | Semi-structured interviews and ethnographic observations | None stated | One trust included in study reducing generalisability; individual recruitment unexplained; researcher role, bias and relationships not addressed |

| Kirby et al (2016) | Identify perceived impacts of shift work on paramedics and provide rationale for further occupational studies | British ambulance staff (n=11): female (n=4); male (n=7) | Ontological focus groups | Researcher influence on focus group and results; subjective analysis by one researcher; self-selection increases sample bias; different sample sizes across groups; reduced generalisability | Small sample size; focus group design unclear; researcher-participant relationship not fully addressed; ethical considerations not addressed |

| Mars et al (2020) | Investigate factors commonly associated with ambulance staff suicides | Ambulance trusts (n=11); ambulance staff (n=15); coroners (n=12); female (n=4); male (n=11); patient facing (n=9); call centres (n=3); other roles (n=3); white British (n=15) | Not stated—appears to be a cross-sectional audit | Small sample size; varied information available for each participant; participants were limited to those employed by the service at the time of data collection; lack of context from wider workforce | Limited study period of 2 years; subjective researcher interpretation of unclassified deaths; confounding factors not comprehensively addressed |

| Newton et al (2020) | Present a case that paramedics fulfil the characteristics of a ‘disruptive innovation’ in modern healthcare | N/A—no numbers given for literatures screened and assessed | Case study | None stated | Study design not explicitly explained or justified; literature search and assessment methods not included |

| Shepherd and Wild (2014) | Investigate the relationship between cognitive appraisals, objectivity and adaptive coping in ambulance staff | LAS ambulance staff (n=45); female (n=14), male (n=31); paramedic (n=18); emergency medical technician (n=27); white British (n=44) | Not stated—appears to be cross-sectional survey using diagnostic scales and questionnaires | Memory bias as retrospective; reliance on subjective measures rather than objective indices; lack of generalisability across traumatic events and population | Small sample size not representative of population; self-selecting sample does not limit bias; measurement classification bias as PTSD diagnostic scale ranges from mild to severe; important confounding factors not addressed |

| Soh et al (2016) | Investigate different dimensions, factor structure and predictors of ambulance staff wellbeing | Ambulance staff (n=490); female (n=237), male (n=253); white British (n=462) | Cross-sectional survey using diagnostic scales | Cross-sectional design does not establish causality as well; smaller sample size and fewer measurement indices compared to previous studies | Cultural demographics not representative; recruitment not addressed; subjective measures; researcher role, bias and relationships not examined |

| van der Gaag et al (2018) | Explore reasons behind disproportionate number of paramedic HCPC referrals | HCPC cases (n=52) | Case analysis, with reference to focus group themes from a previous study in series | Small sample size; limited focus group locations | Random sampling method not explained; limited study period of 2 years; researcher role, bias and relationship not addressed; conflict of interest noted in that corresponding author was previously HCPC chair |

| Wankhade (2016) | Analyse the changing nature, scope and consequences of intense ambulance work, and staff coping behaviour | Ambulance staff (n=70+); board executives, managers, paramedics, call handlers and dispatchers; observations (n=100 h) | Semistructured interviews and ethnographic observations | Potential lack of generalisability in other contexts; paramedic education routes and qualifications changed between the study period and publication | Participant recruitment not addressed; researcher role, bias and relationship not examined; unclear data collection and analysis methods |

EOC: emergency operations centre; HART: hazardous area response team; HCPC: Health and Care Professions Council; HEMS: helicopter emergency medical service; LAS: London Ambulance Service; MERIT: medical emergency response incident teams; NWAS: North West Ambulance Service; h: hours

HCPC: Health and Care Professions Council; LAS: London Ambulance Service; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; h: hours

Retention findings

Studies addressing retention (n=6) reached similar conclusions. Ambulance service work is inherently rewarding and meaningful, attracting those seeking altruistic or exhilarating roles (Clompus and Albarran, 2016; Coxon et al, 2016; Granter et al, 2019).

However, trusts are facing untenably high turnover and acute staff shortages, adding pressure to an already fraught service (Coxon et al, 2016; Wankhade, 2016; Granter et al, 2019; Newton et al, 2020). Both occupational and organisational factors compound this problem. Coxon et al (2016) found that high EOC staff turnover is associated with stress. The paramedic role specifically has some of the highest vacancy rates, which are associated with a reduced ability to cope with increasing organisational demands (Granter et al, 2019).

A lack of recognition, low pay in relation to responsibilities and health risks, poor leadership and management, increasing managerial oversight (Clompus and Albarran, 2016), along with a lack of resources, support, feedback and progression, enforced overtime and higher public expectations all affect how staff feel in their roles (Wankhade, 2016; Newton et al, 2020).

This results in demoralised and disillusioned staff seeking employment elsewhere (Wankhade, 2016; Newton et al, 2020), or retiring prematurely because of poor work-related mental and physical health (Soh et al, 2016).

Sickness absence findings

Ambulance staff have the highest sickness absence rates in the NHS, and a significantly greater rate than the national occupational average (Wankhade, 2016). This contributes to the severe service pressure impacting staff health and retention (Coxon et al, 2016; van der Gaag et al, 2018).

Of the studies examining staff sickness (n=8), four recognise poor mental health as a substantial compounding factor (Clompus and Albarran, 2016; Coxon et al, 2016; Soh et al, 2016; Mars et al, 2020), while Wankhade (2016) notes the wider evidence base may suggest poor work-related mental and physical health is a causal factor. Soh et al (2016) suggest staff wellbeing is an important predictor of productivity, absence and turnover, with multiple propagating factors including a lack of role recognition (Coxon et al, 2016), poor working conditions, inadequate managerial support and contact—particularly surrounding absences (Mars et al, 2020; Newton et al, 2020)—along with inappropriate sickness management and policy implementation (Kirby et al, 2016; Wankhade, 2016).

Wellbeing findings

All 13 articles addressed staff wellbeing. A thematic analysis was conducted because of this topic's complexity. Three main themes were identified: staff, patient and organisational impacts. One subtheme explores specific staff mental health concerns.

Staff impact

The demanding and complex nature of ambulance service work (Gallagher et al, 2016) is inherently stressful, with staff at a significantly higher risk of poor health than the general population (Drury et al, 2013; Shepherd and Wild, 2014; Clompus and Albarran, 2016).

Acute and chronic profession-specific stressors (e.g. environmental instability and risks, trauma exposure and high-stake decision-making) are exacerbated by a changing system that cannot handle the unsustainably growing work intensity (Shepherd and Wild, 2014; Clompus and Albarran, 2016; Soh et al, 2016; Wankhade, 2016; Granter et al, 2019; Mars et al, 2020; Newton et al, 2020).

The service's struggle to cope with increasing demand places excessive organisational pressures and workloads on staff (Coxon et al, 2016; Mars et al, 2020; Newton et al, 2020). Workplace stress contributes to higher rates of staff dissatisfaction, bullying, sexual harassment and suicide and causes concern from the paramedic-regulating body, the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) (Gallagher et al, 2018; van der Gaag et al, 2018; Mars et al, 2020; Newton et al, 2020).

Staff also experience more injuries and physiological illnesses (Wankhade, 2016; Gallagher et al, 2018; Granter et al, 2019; Mars et al, 2020). EOC staff are uniquely stressed as they are the first point of contact for the public during medical emergencies, even though their frontline role is not patient facing (Coxon et al, 2016); a role-specific study found enforced risks, such as working overtime that staff have not signed up for and excessive driving times (particularly when using emergency driving exemptions), render the paramedic profession one of the most dangerous in the world (Granter et al, 2019).

Poor staff wellbeing is affected by the same factors that impact on retention and sickness (Clompus and Albarran, 2016; Coxon et al, 2016; Mars et al, 2020; Newton et al, 2020). This is heightened by confusion around professional identities arising from rapidly evolving scopes of practice, more emotionally demanding patient needs and the shift from emergency to urgent care (Gallagher et al, 2016; Wankhade, 2016; Gallagher et al, 2018; van der Gaag et al, 2018; Newton et al, 2020).

A lack of control, resources, training and development, alongside poor communication and managerial support, are key problems resulting in cumulatively poor staff health and morale (Shepherd and Wild, 2014; Clompus and Albarran, 2016; Coxon et al, 2016; Kirby et al, 2016; Soh et al, 2016; van der Gaag et al, 2018). Staff feel overworked and undervalued (Coxon et al, 2016) and do not have time to engage in coping mechanisms such as workplace peer support (Clompus and Albarran, 2016), reflecting, debriefing and supervision (Drury et al, 2013; Gallagher et al, 2016; van der Gaag et al, 2018). Changing shift patterns, long hours and compulsory shift extensions mean staff have little time to recover, eat well or partake in regular exercise, all of which promote positive wellbeing (Coxon et al, 2016; Kirby et al, 2016).

Mental health concerns

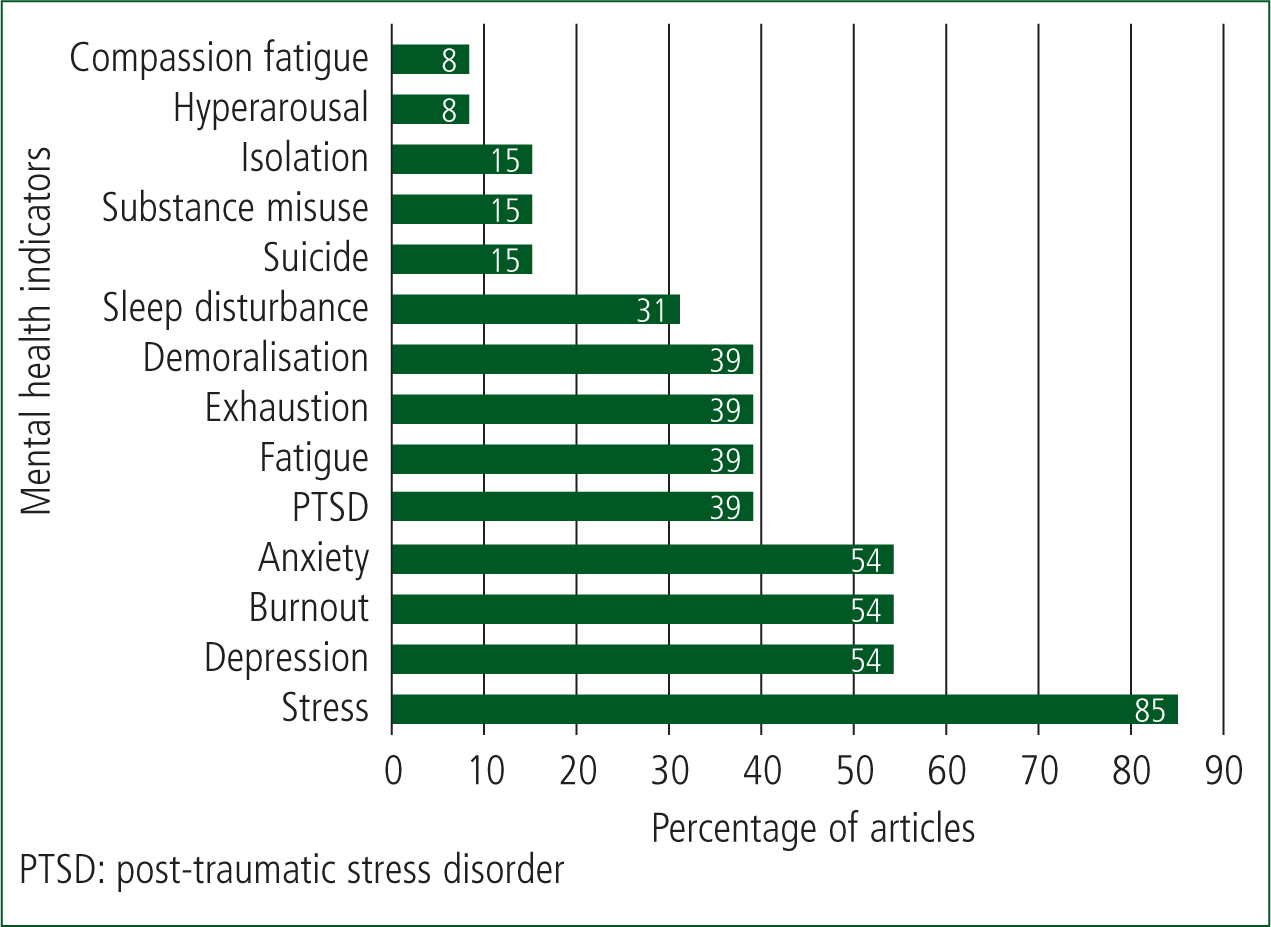

Most articles were concerned about levels of staff stress, with 54% specifically identifying anxiety, depression and burnout as commonly developed conditions. Almost half documented post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), fatigue, exhaustion (including emotional) and demoralisation. Substance misuse and suicide were described in 15% of studies (Figure 2).

Rather than reflecting the prevalence of mental health conditions, these numbers demonstrate that the mental wellbeing of staff is a concern, despite a limited evidence base. For example, Mars et al. (2020) found an elevated suicide risk in ambulance staff (75% greater in male paramedics than the national average) but identified research was lacking in this field. Additionally, Clompus and Albarran (2016) report that mental health charity Mind (2015) found 87% of emergency service staff, including ambulance workers, experience low mood and poor mental health after starting their job. This can be partly attributed to a negatively affected work-life balance (Coxon et al, 2016).

Patient impact

Public misuse of the service and overly cautious triage systems designed for time-critical emergencies result in over-prioritised and clinically unnecessary responses for the majority of patients, who do not require emergency care; responses to genuine emergencies are also delayed as a result (Wankhade, 2016; Granter et al, 2019; Newton et al, 2020). This contributes to increased organisational demand, creating unnecessary stress. Normalising these stressors has meant they are not adequately addressed, resulting in low staff health, morale and job satisfaction (Granter et al, 2019).

Poor staff wellbeing has performance consequences from increased error prevalence (clinical and conduct), as well as occupational accidents, which risk staff and public safety, and directly impact patient care (Clompus and Albarran, 2016; Coxon et al, 2016; Kirby et al, 2016; Gallagher et al, 2018; van der Gaag et al, 2018). These risks, while poorly evidenced (Wankhade, 2016), are supported by van der Gaag et al (2018), who found that a high frequency of paramedic HCPC self-referrals concerned occupational incidents, inadequate patient care, and were attributed to work-related stress. Newton et al (2020) suggest the situation is not improving.

Organisational impact

Organisational failings (including leadership and managerial) have resulted in poor working conditions where staff feel unsupported and not cared about, threatening basic service delivery (Kirby et al, 2016; Mars et al, 2020; Newton et al, 2020). For example, Soh et al (2016) found perceived organisational support correlates with staff concern for organisational objectives, meaning staff who feel unsupported can care less about their job. A lack of awareness about individual staff circumstances because of service restructuring and departmental centralisation creates additional communication and care barriers (Kirby et al, 2016; Granter et al, 2019).

Outdated and sometimes toxic workplace cultures exacerbate this. For example, the ‘male coping’ culture is harmful to good mental health (Clompus and Albarran, 2016). Hierarchical, target-driven, blame, punishment and disproportionate risk-aversion cultures create conflict as well as ingrained feelings of stress (Drury et al, 2013), pressure (Granter et al, 2019), fear, frustration and mistrust (Drury et al., 2013). This inhibits professionalism (Gallagher et al, 2016), fuelling resistance to change (Drury et al, 2013; Wankhade, 2016; van der Gaag et al, 2018), and impeding service improvements (Newton et al, 2020).

As with professional identities, there are disparities between how the service is viewed by staff, other professionals, the public and the media, resulting in unclear or, in the last cases, high and unreasonable expectations (Wankhade, 2016; Gallagher et al, 2018).

Finding its place within the NHS as a professional healthcare provider in itself proves difficult for the ambulance service when it is still often viewed as a transport or emergency service. This is compounded by variable trust performance and being the fallback service used to safety-net gaps and failings in other NHS services (Newton et al, 2020).

AQI impact

There is consensus the AQIs are too restrictive and stressful (particularly time targets), adding pressure to an already overloaded system, and acting as a barrier to staff and patient wellbeing improvement (Drury et al, 2013; Clompus and Albarran, 2016; Wankhade, 2016; Gallagher et al, 2018; van der Gaag et al, 2018; Granter et al, 2019). Table 4 shows the findings from the AQI search.

| Study | Methods | Ambulance quality indicator (AQI) findings | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brady and Northstone (2017) | Interviews and thematic analysis | ‘Hear and treat’ AQI does not properly represent emergency operations centre clinical hub responsibilities; it does not encompass or measure all hub roles; it leads to role ambiguity as staff place emphasis on AQI definition rather than actual duties | Improved role clarity; re-evaluate the ‘hear and treat’ AQI definition; greater inclusivity required |

| Coster et al (2018) | Consensus and modified Delphi study | Many of the AQIs, particularly response times, do not adequately reflect the breadth of care ambulance services provide | Wider measures are required, including patient safety and experience |

| Heath and Wankhade (2014) | Case study | Patient experience not currently reported; risk of certain indicators being stressed over others; weak correlation between indicators and actual performance; unclear if or to what extent staff have contributed to formulating the AQIs | Research into the development and application of AQI dashboards and how the two performance measures interact; investigate service use and how it is valued by patients and staff; AQI refinement involving different stakeholders |

| Phillips (2018) | Literature review | Internal and external factors influence the AQIs, e.g. demographics and geography, making it harder for some services to meet targets than others | None relevant to AQIs |

| Santa et al (2018) | Quantitative questionnaires | Patient safety is a vital healthcare quality component and necessary for effective safety management systems; blame cultures result in staff who are demoralised and afraid to admit mistakes, and also result in higher turnover and service costs, hindering quality improvement; clinician-patient relationship influences patient satisfaction and is a crucial quality indicator | Blame-free culture with environment enabling open, honest communication; managers need to demonstrate a commitment to quality and safety culture; promote organisational leadership and safety by increasing practices, awareness and resources focused on these |

| Santana et al (2019) | Literature review | Patient-centred care requires systematic measurement and evaluation; indicators should be evidence based to improve healthcare quality; indicators do not typically include patient and family experiences; wellbeing measures are necessary and important; the lack of consistency across healthcare services in defining and measuring quality makes it difficult to identify indicator improvements; the primary focus has been on specific diseases as indicators | Indicators need to reflect patient and family perspectives, although it is difficult to categorise these into standardised measures; more generic measurement is needed, not just specific disease focus |

| Wankhade (2011) | Literature review, case study and interviews | Public health sector is more risk adverse; objectives less well defined; indicators may be chosen for measurement ease, not importance; restricted view of operational complexity; fixation on measures rather than underlying objectives; tunnel vision on measures at expense of other, more relevant areas; meeting short-term or narrow objectives at the expense of more important ones; non-evidence-based response time targets are too simplistic; the patient is treated as a number; organisational paralysis in a too-rigid system; performance measurement and organisational culture together may inhibit reform; targets demotivate and demoralise staff | Take into account unintended consequences when setting performance indicators and identify whether they can be realistically achieved before setting them |

| Wankhade (2012) | Literature review, interviews and observations | Performance judged against meeting simplistic targets; fear of personal failure and repercussions if not met; targets can impact performance and organisational culture; disjointed subcultures and thinking; target-driven managerial pressure on staff; directly impacts morale | Further research and cross-comparative studies required in this area |

| Wankhade et al (2018) | Literature review, interviews and observations | Indicators are controversial; they may inhibit service roles; AQIs were reported to permit more time to find right care rather than quickest; indicators more wide-ranging, but response targets are still stressed at the expense of others; interaction between culture and performance measurement affects policy and practice; targets inhibit change, perpetuating culture; poor staff morale if targets are too high and unrealistic, which some managers believe might be the case | Further research into: why response time targets still dominate and how the AQI dashboard impacts views; the effects of performance management on culture; and the role of higher education and training |

Discussion

Findings

The results overwhelmingly evidence that poor retention and high staff sickness rates in the UK's NHS ambulance service are intrinsically linked with staff wellbeing (Soh et al, 2016; Granter et al, 2019).

Organisational pressures, culture and patient demand influence staff wellbeing and are, conversely, affected by how staff feel and cope in their roles (Coxon et al, 2016; Gallagher et al, 2016). These pressures are a common denominator in staff—many of whom share altruistic values (Clompus and Albarran, 2016)—taking many sick days despite knowing it could compromise patient care (van der Gaag et al, 2018), resigning from roles they value (Newton et al, 2020) and who are dissatisfied and suffering (Wankhade, 2016; Mars et al, 2020).

Although small, the UK peer-reviewed evidence shows these concerns far exceed those in the general population (Shepherd and Wild, 2014; Wankhade, 2016). The possibility that modern-day standard operating procedures are putting staff at risk demands urgent investigation (Granter et al, 2019). Recent studies suggest staff wellbeing measurement is no longer just a positive step but essential for maintaining staff health, high-quality patient care and achieving organisational success (Kirby et al, 2016; Soh et al, 2016).

Critical analysis

While all included articles possess intrinsic worth and value, addressing a notable problem by creating new evidence or filling gaps in small evidence bases, one finding from the analysis was that confounding factors were not always thoroughly considered.

An important question is, therefore, whether workplace stressors can be deemed responsible for poor wellbeing, retention and sickness rates, instead of, for example, personal difficulties or pre-existing health conditions (Dodd, 2017). Similarly, it is also important to recognise the influence that physical health (particularly work- and non-work-related musculoskeletal injuries and disease burdens) and mental health can have over each other (Barrett, 2016; Anderson, 2019; Ricciardelli et al, 2019).

According to What Works Wellbeing (2018), an organisation that informs the NHS (Litchfield, 2019), wellbeing is subjectively personal and affected by different environmental factors, including skills, employment and personal finance. Improving wellbeing must start with measuring it, which the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has contributed to doing (What Works Wellbeing, 2019).

Almost consistently since 1995, healthcare workers have had the highest national occupational sickness absence rates and average days lost to sickness per worker in the labour market. For example, in 2018 (the most recent data available) the percentage of working hours lost to sickness absence in the healthcare sector was 3.1, compared with 2.9 and 2.5 in the central and local government sectors respectively, 2.7 in the public sector and 1.8 in the private sector (ONS, 2019).

Poor mental health was one of four (of 11) top reasons for public sector absences, accounting for 10.2% in 2018, less than ‘other reasons’ at 11.1%, musculoskeletal problems at 14.9% and minor illnesses at 33.7% (ONS, 2019).

The ONS (2017) also reports an increased suicide risk in health professionals, with a 24% greater risk in female practitioners than the national average and higher suicide completion in male practitioners than those in other occupations, possibly from readily available knowledge of and access to lethal means (ONS, 2017). In one 10-year period, it is thought 33 paramedics died by suicide (ONS, 2016), although there is no information available to identify causal factors. Ambulance staff are typically the unhappiest within the NHS and most eager to leave (NHS Survey Coordination Centre, 2019).

A recent survey with 977 respondents attributed chronically poor retention to reduced staff wellbeing (Harris, 2019). Supporting the idea that organisational and occupational pressures in the ambulance service contribute significantly to staff stress levels is pertinent; Gallagher et al (2018) and van der Gaag et al (2018) recognise its influence on higher rates of paramedic HCPC self-referrals, including incidents outside work. As seen with COVID-19, acute stressors exacerbate the problem (Tang et al, 2020).

It is established that workplace environments influence wellbeing (NHS Employers, 2018) and, considering this alongside the local and national ambulance-specific findings detailed in this study, it can be inferred that service stressors directly contribute to high rates of poor staff health, sickness and turnover (Coxon et al, 2016; Newton et al, 2020). This conclusion has been upheld in a government report by Bryson et al (2014). The extent to which trusts should take responsibility, however, must be considered. Although the HCPC's (2014) standards of proficiency dictate paramedics must ‘understand the importance of maintaining their own health’ (with little guidance on how), the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 (HSWA) stipulates employers have a legal responsibility to take care of the health and safety of their employees.

The HSWA mandates employers enforce workplace procedures, policies and statutory training to equip staff in minimising risks. To date, the emphasis has been on physical risks. A comparatively smaller focus on mental wellbeing prompted an independent government-commissioned review, which found Health and Safety Executive guidance needed revision to ensure employers understood their duty to assess and manage poor staff mental health (Stevenson and Farmer, 2017). This was accompanied by a political pledge to update the HSWA to allow better provision for mental wellbeing.

As this pledge went unfulfilled, however, a letter signed by more than 55 mental health, education and business leaders (including ambulance service trade unions and charities), was sent to the government, holding it accountable (Watson-Gandy and Keenan, 2018). The request, supported by hundreds of thousands of people, reiterated the duty of care organisations have towards preventing and managing staff mental illness, which costs employers up to £42 billion annually (Watson-Gandy and Keenan, 2018; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2019). This professional, political and public agreement (including by NICE, 2019) supports that employers need to prioritise and invest in their staff's spectrum of health—not just because it affects patient care.

As a professional medical provider, the ambulance service could be at the forefront of this innovation (Newton et al, 2020), but it needs to start getting the basics right, identifying ‘invisible’ workplace health risks and recognising that those who are struggling, who feel unsupported or that they are a burden, may find it hard to ask for help (Mildenhall, 2012; Naumann et al, 2017).

It is undisputed and documented in national ambulance guidelines (JRCALC, 2019) that staff wellbeing affects job performance and patient care quality (Clompus and Albarran, 2016; Gallagher et al, 2018); fatigue, for example, can prove dangerous (AACE, 2019b). Yet there are no staff wellbeing measures within the AQI framework (NHS England, 2019b), despite its intention to achieve quality care (Santana et al, 2019).

The risk-averse AQIs are wider ranging than their predecessors, reportedly allowing more time to allocate a correct response (Wankhade et al, 2018). However, Newton et al. (2020) claim they are incompatible with patient and staff needs. The AQIs are controversially thought to be too limited (Wankhade and Brinkman, 2014), restrictive and simplistic in nature given their objectives (Wankhade, 2012; Brady and Northstone, 2017; Coster et al, 2018).

As well as setting some targets that are difficult to meet, such as ambulance response times, they negatively impact staff welfare and detract from care quality (Wankhade et al, 2018). This is because the framework has a narrow focus on a few health presentations and an emphasis during most incidents on arrival times rather than on the care provided. They encourage a target-driven culture, with managerial pressure to ‘treat the clock’ instead of the patient (Wankhade, 2016; Gallagher et al, 2018).

This exacerbates fear and blame cultures in case of failure (van der Gaag et al, 2018), demotivating and demoralising staff, reducing performance (Wankhade, 2011; Santana et al, 2019), and culminating in increased turnover and service costs, while creating a barrier to discussing mistakes (Santa et al, 2018).

Wankhade (2011) theorises that some indictors at least were chosen for ease rather than importance, suggesting they are not rooted in evidence; according to Santana et al (2019), this will undermine improvement. Based on the evidence, the authors argue that staff wellbeing measures should not be included in the AQIs; instead, the framework's efficacy needs to be reviewed.

Factoring staff wellbeing and resilience into policy, management and emergency planning is vital for mitigating the structural, systemic and resource stressors that negatively affect staff and their ability to meet patient needs (Mildenhall, 2012; Drury et al, 2013).

The NHS workforce health and wellbeing indicators (Table 2) or the more recent workforce stress and the supportive organisation framework, launched by Health Education England and aimed at structuring improvement processes for health and social care employers (Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, 2019), may provide starting foundations. However, at present, neither frameworks are mandatory, enforced or well disseminated. Anecdotally, five of six EOC, operational and senior managers at one ambulance trust had not heard of them (personal correspondence from EOC manager dated 16 May 2020).

Nonetheless, measuring staff wellbeing is vital (Kirby et al, 2016), and it can be concluded from the evidence that proactive development and implementation of a comprehensive, compulsory and service-specific staff wellbeing assessment and improvement protocol is warranted (Soh et al, 2016). Including the mental health indicators set out in Figure 2 as a measure of prevalence is recommended by the present study's authors.

The service should, additionally, address its professional identity (medical versus emergency or transport service) and inhibiting cultures to create an environment where staff wellbeing and patient care can thrive (Wankhade, 2016; Gallagher et al, 2018; Santa et al, 2018).

Reshaping organisational structure may also be of benefit (Manley et al, 2016), as Kirby et al (2016) found departmental centralisation can create barriers to support and communication. An EOC manager who spent more than 25 years at one trust has shared similar concerns about increasing managerial layers, where those making decisions affecting staff are unaware of staff needs, negatively impacting staff satisfaction and performance (personal correspondence dated 16 May 2020).

Although NHS England (2018) advises that positive change requires top-down direction and should be led by chief executives and boards in consultation with staff, there are numerous layers of management between frontline workers and those in senior roles, which prevents this. Communication will facilitate the identification of shared wellbeing values and what matters to staff (e.g. recognition, support, training and flexible working) (Coxon et al, 2016; Anderson, 2019), which is critical for improving management and leadership outcomes (Ogbonnaya and Daniels, 2017).

As one senior trust manager noted, collaboration between trusts is also essential for sharing ideas, learning and committing to national staff wellbeing improvements, as promised in the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS Improvement, 2019). These steps are predicted to improve staff wellbeing, resilience and performance, reduce turnover, sickness absence and associated costs, which in turn will positively impact patient care.

Limitations

The study's search terms and databases were not as inclusive as they might have been because of time restrictions. Search strategies tailored to each database's search functions were considered to enhance results but would have challenged protocol consistency.

Although potentially insightful, a focus on whether and how staff wellbeing should be prioritised meant relative theme importance was not assessed. A comparative analysis of pre-AQI conditions was not carried out because resources were limited; however, the framework's impact on staff wellbeing was addressed within this review.

Finally, with limited population-specific research available, findings should be interpreted with caution and may vary between and within trusts.

Conclusion

Alongside illustrating the urgency for a formal and prioritised staff wellbeing review, this article has demonstrated the need for more research focusing on this area. Staff wellbeing assessment and intervention outcome measurement must be evidence based if wellbeing is to be sustainably improved. Workplace stressors must be examined, including the target-centric AQIs. Although the AQIs are supposed to drive improvement, they instead compound poor staff health and therefore patient care quality, possibly because of a lack of evidence-based grounding.

Trusts need to recognise that staff wellbeing is a current and unprecedented issue in the ambulance service compared with other occupations and that the service has a legal and ethical duty to take remedial action.

Adopting a firm identity as a professional medical provider may empower trusts to place the same emphasis on caring for and protecting staff as they do on patients. This will benefit the service by reducing turnover, staff sickness and associated costs; it will benefit staff by improving their health and satisfaction; and it will improve patient care quality by increasing staff engagement and performance. In this way, UK NHS ambulance trusts could pioneer a world-class service where all stakeholders thrive.

Recommendations

This study makes the following recommendations: