More than 230 million medication errors are estimated to occur annually in England (Elliott, 2021). Of these, 21% happen at the prescribing stage and over 50% have the potential to cause moderate to severe patient harm (Elliott, 2021). Prescribing errors, including those in prescription writing, are relatively common but largely preventable causes of harm, occurring in 4.9% of prescriptions in primary care (Avery, 2012) and 7–10% on medical wards (Maxwell, 2016). It is hoped that, by highlighting the legal requirements and best practice recommendations for prescription writing, this article will reduce the risks associated by ensuring a legal, clear and complete prescription.

Legal requirements

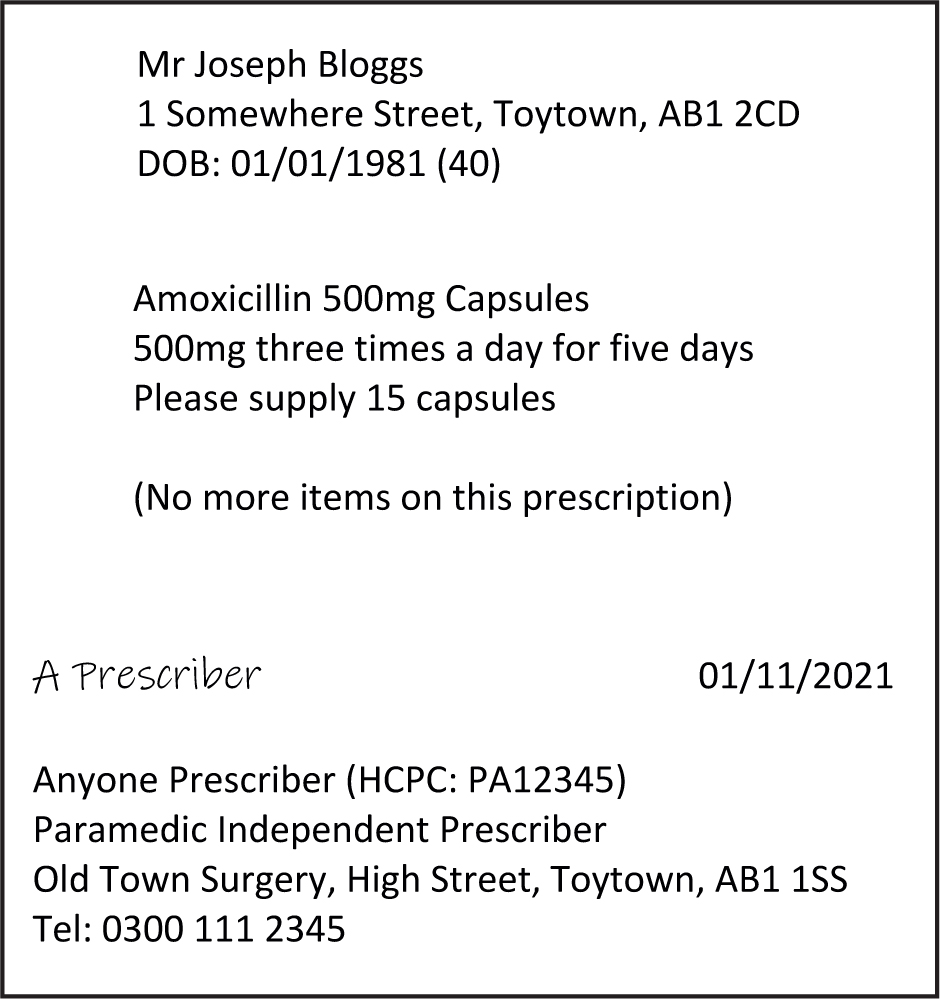

The legal requirements for writing a prescription are defined by regulation 217 of the Human Medicines Regulations 2012. For any prescription-only medicine to be sold or supplied, the prescription must:

In lieu of a physical signature for electronic prescriptions, regulation 219 of the Human Medicines Regulations 2012 allows an advanced electronic signature to be used when the prescription is sent to whoever is going to dispense it as an electronic communication (this can be done directly or through intermediaries). The advanced electronic signature must be under the prescriber's sole control and be capable of identifying the prescriber, uniquely linking them to the prescription and any subsequent changes (e.g. to the drug, directions or quantity after the initial prescription has been electronically signed).

In practice, this electronic signature is often achieved by the prescriber entering the passcode to their NHS smart card to sign a prescription. This requires employing organisations and/or electronic prescribing system providers to set up the required permissions to allow paramedic prescribers to prescribe electronically, which led to delayed implementation, particularly among early adopters (Stenner, 2021).

Legal responsibility for prescribing lies with the health professional who signs the prescription and it is the responsibility of the individual prescriber to prescribe within their level of competence (NHS England, 2018).

Paramedic independent prescribers are still awaiting the Misuse of Drugs Regulations (MDR) [2001] to be amended to be able to independently prescribe the following controlled drugs (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, 2019; College of Paramedics, 2021a):

In addition to the above, there are further requirements for prescribing controlled drugs in MDR schedules 2 and 3. This includes providing the following information:

Whether a medication is a controlled drug can be checked in the British National Formulary (BNF) (Joint Formulary Committee, 2021) drug monograph in the medicinal forms section. The BNF states the MDR schedule, which can differ between formulations. For example, morphine oral solution 10 mg/5 ml comes under schedule 5 (so has no additional controlled drug prescription requirements) while morphine oral solution 20 mg/ml and morphine 10 mg tablets are in schedule 2.

An incomplete or incorrect prescription may result in delays or omissions in patient care while it is clarified or amended. To minimise this, the BNF guidance section provides a reminder of the legal requirements and recommended practice for writing prescriptions for both prescription-only medicines and controlled drugs.

Reducing errors

As paramedic prescribing is a recent introduction, there is currently a lack of data on the prevalence or types of paramedic prescribing errors.

In general, prescription writing errors commonly occur because the prescription is incomplete (i.e. missing a drug/dose/strength/formulation/route etc), is incorrect (i.e. wrong patient/drug/dose/frequency/route etc) or is unclear (often because of handwriting) (Franklin, 2011; Avery, 2012; Maxwell, 2016). Best practice recommendations to help reduce these prescription writing errors include the following (College of Paramedics, 2021b; Joint Formulary Committee, 2021):

While the above best practice recommendations suggest what can be physically written on a prescription to minimise errors, it is recognised that the causes behind many healthcare errors including those associated with prescribing are multifactorial and will include task, individual and system factors (Avery, 2012; Maxwell, 2016; Puaar, 2018).

As the Royal Pharmaceutical Society's A Competency Framework for All Prescribers (RPS, 2021) requires prescribers to use available tools to improve their prescribing practice, and these may present opportunities to reflect on potential or actual prescribing errors. Potential tools could include supervision, observation, portfolios, competency-based assessments, prescribing data analysis, audits, case-based discussions, personal formularies or seeking feedback.

Electronic prescribing

While not all environments that paramedic prescribers practise in support electronic prescribing, increasing its use is a Department of Health and Social Care (2018) priority as part of the World Health Organization (2017) Medication Without Harm challenge, which aims to reduce severe avoidable medication-related harm globally by 50% within 5 years.

The use of electronic prescribing has been shown to improve safety, prescription clarity and the quality of discharge communication (Mills, 2017). NHS Digital (2021) reports that electronic prescribing is more efficient with less time spent dealing with prescriptions and queries. A further advantage of prescribing electronically is that it makes it easier to undertake prescribing analyses or audits as part of continuing professional development as a prescriber (College of Paramedics, 2021b; RPS, 2021).

The use of electronic prescribing systems reduces the frequency of prescribing errors; however, they do not completely eradicate them and change the types of errors that occur (Donyai, 2008). While electronic prescribing reduces errors caused by illegible or incomplete prescriptions, it increases incorrect selections of medication/route/dose/frequency/formulation/route from drop-down menus; this could, for example, lead to medication being prescribed twice daily rather than twice a week (Donyai, 2008).

Care must be taken with medicine names that look or sound alike to prevent the wrong medicine being selected (Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, 2018). A common example seen in practice by the author since the introduction of electronic prescribing is the inadvertent prescribing of penicillamine, usually used as a disease-modifying drug for rheumatoid arthritis. The antibiotic penicillin V comes under the approved drug name phenoxymethylpenicillin in electronic prescribing systems; a prescriber typing ‘penicillin’ can inadvertently select penicillamine. Another common example could be attempting to prescribe the antiemetic metoclopramide; typing only ‘met’—depending on the set-up of different electronic prescribing systems—this can lead to the inadvertent selection and prescribing of metaraminol, metformin or methadone. An action as simple as typing in the full drug name can reduce the potential for error.

It is always worth double checking that the medicine, formulation, route, strength, dose, frequency and quantity intended have been selected before electronically signing the prescription. Electronic prescribing systems have different set-ups and degrees of prescription checking or clinical decision support (CDS) so differ in their abilities to prevent prescribing errors (Fox, 2019).

Built-in CDS error alerts can be useful to highlight and reduce prescribing errors; however, it is important to be aware that prescribers can become overly reliant on the alerts to the extent that they stop thinking and rely entirely on the system alerts or, conversely, become fatigued (Lyell, 2017). Prescibers may become so accustomed to having alerts flash up on their screen for lower-risk warnings that they end up clicking to accept them without actually considering what the alert is telling them and what the implications could be for the patient.

Therefore, paramedics may wish to discuss any prescribing errors that have arisen within their organisation with their prescribing lead or try to make prescribing errors on a ‘test’ patient electronic record to gain an awareness of the flaws of a workplace's particular electronic prescribing system.

Conclusion

Prescriptions that are incomplete, unclear or incorrectly written have the potential to cause harm to patients. Paramedic prescribers can minimise these risks by ensuring that the legal prescription requirements and best practice recommendations are met, which are summarised in the BNF. The BNF can also be used to check the legal status of individual medicines to ensure that a medicine that is a controlled drug is not inadvertently prescribed.

Checking the BNF and other resources such as the Electronic Medicines Compendium or national guidelines can reduce prescribing errors as can using support networks and undertaking professional development activities in relation to prescribing.

The use of electronic prescribing systems can help to reduce prescribing errors, particularly those resulting from unclear or incomplete prescriptions, but care is needed because they increase errors resulting from the incorrect selection of drop-down options or by selecting an incorrect drug with a similar name.