Life-threatening emergencies, while stressful, are not experienced by prehospital clinicians all that often (Wardrope and Mackenzie, 2004). Of the 9.2 million 999 calls received by NHS ambulance services in England in 2019–2020: 30 908 required cardiopulmonary resuscitation by an ambulance crew; 6379 were diagnosed with ST-elevation myocardial infarction; 34 599 were assessed for a stroke; and 33 896 were suspected to have sepsis (NHS, 2021). These account for just over 1% of all 999 calls received in this period.

Therefore, many of the patients who call 999 are not experiencing an easily recognisable life-threatening condition. However, reports into serious untoward incidents have shown that some are related to the assessment of the patient (London Ambulance Service. 2015; West Midlands Ambulance Service, 2021). To ensure paramedics can recognise and manage these patients, they require training and practice.

Wardrope and Mackenzie (2004) set out a system of assessment for the patient with emergency care needs—the System of Assessment and Care (SOAPC) of the Primary Survey Positive Patient. This article has reviewed and revised this system to provide an up-to-date structure of patient assessment with the aim of helping paramedics in practice. The original article focused on the assessment and management of a medical patient so this article will also concentrate on medical emergencies. Trauma patients will be covered later in the series.

Objectives

This study aimed to:

What is a primary survey?

A primary survey is designed to recognise immediately life-threatening conditions and manage patients before moving onto the next step (World Health Organization and International Committee of the Red Cross, 2018).

Patients experiencing an immediate threat to life are categorised as primary survey positive patients and require a structured approach. If these priorities are not managed in the appropriate order, the critically ill or injured patient is likely to deteriorate rapidly into cardiac arrest and their chances of survival decrease (Resuscitation Council UK, 2021).

Although the order of this survey was originally designed for use in hospital to identify patients at risk of cardiac arrest, it has been used effectively in the prehospital environment for many years.

It should be noted that most acute medical patients will not present as primary survey positive. Many will be talking normally, fully orientated, not pale and clammy, not breathless and will have a normal pulse. This reduces the likelihood that they have a life-threatening condition but it does not eliminate the possibility so further assessment is required. It is important to remember that there is evidence that important clinical signs may be missed, misinterpreted or mismanaged leading to clinical errors in prehospital practice (Wardrope and Mackenzie, 2004). That being said, if you suspect a patient has a condition, you can expect them to develop a characteristic symptom (Box 1).

Carrying out the primary survey

Many resources that describe the assessment and management of an acutely unwell patient are available. The following summary of the primary survey is taken from: Advanced Life Support Group (ALSG, 2010); Blaber and Harris (2011); Nutbeam and Boylan (2013); Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE, 2019); Greaves and Porter (2021); and Resuscitation Council UK (2021).

As paramedics approach the scene of a 999 call, they need to consider their safety, the safety of those around them and the safety of the patient. A dynamic risk assessment is undertaken. Personal protective equipment is donned and additional resources requested as per local guidelines and depending on the type of call. Immediately upon arrival, clues to the mechanism of illness or injury are noted when looking at the patient and their surroundings. As the paramedic introduces themselves, so begins the primary survey.

The order of assessment and management of the primary survey is noted by the mnemonic <C>ABCDE (Table 1).

| Primary survey | Red flags |

|---|---|

| Airway |

Reduced consciousness |

| Breathing |

Cyanosis |

| Circulation |

Profound pallor |

| Disability |

Hypoglycaemia |

| Exposure |

Purpuric rash |

Following a structure such as this ensures nothing is missed.

<C>: catastrophic haemorrhage

This was added to the primary survey by army medical staff who recognised there were similarities between civilian trauma and battlefield trauma (Hodgetts et al, 2006). It was noted that if heavy bleeding was not managed immediately, the patient would not reach C in the primary survey as they would exsanguinate before the airway and breathing were managed.

In the context of medical cases, most catastrophic haemorrhage will be occult and not obvious at this stage of the primary survey so it is omitted from the assessment of acute medical patients.

A: airway

On approaching the patient, the paramedic should introduce themselves. As well as being good practice, it will help assess airway patency and level of responsiveness.

If the patient responds and can speak in full sentences without any other audible sounds, then the airway is patent. If the patient is unresponsive or there is evidence of gurgling, stridor, wheezing, grunting or the voice sounds raspy, the airway may be obstructed and further assessment is required.

Gurgling indicates that there is fluid in the airway. Stridor, grunting or raspy voice sounds indicate the upper airway is obstructed. Causes include choking on a foreign body or anaphylaxis. Wheezing indicates the lower airways are obstructed.

B: breathing

Once the airway has been assessed and managed, breathing should be assessed. Is the patient using accessory muscles to assist with their breathing? Is there evidence of cyanosis? Is the breathing regular or erratic? Is chest movement equal on both sides? What is the respiratory rate? What is the oxygen saturation (SpO2) reading?

Use of accessory muscles, cyanosis, erratic breathing patterns, paradoxical chest movement, a respiratory rate of <10 or >29 per minute and SpO2 of <95% all require further assessment and management before moving on.

C: circulation

Next to be assessed is circulation. Note the patient's complexion and skin temperature. A pallid, cold, clammy or mottled complexion indicates poor perfusion, which may be because of myocardial infarction (MI), hypovolaemia or sepsis. Jaundice indicates issues with the liver. Look for signs of concealed haemorrhage. Clues include haematemesis and melaena

Note the presence, strength, rhythm and rate of the radial pulse. Absence of the radial pulse may indicate poor perfusion. Irregularities of the pulse should be investigated with an electrocardiogram (ECG) before moving on. Capillary bed refill time and blood pressure should also be assessed to ensure adequate perfusion.

D: disability

When the patient was first addressed, their response should have been noted using the AVPU (alert, verbal, pain, unresponsive) scale. If it is abnormal, a capillary blood glucose reading (BM) should be taken to rule out diabetic emergency.

Note any abnormal movements, slurred speech or facial drooping that may indicate a stroke or seizure. Note any neck stiffness or photophobia that may indicate meningitis.

Assess the patient's pupils to ensure that they are equal and reactive to light. Unequal and/or sluggish pupils may indicate raised intracranial pressure. Dilated or constricted pupils may indicate drug overdose.

The Glasgow Coma Scale assessment can now be done (see Box 2 for adults and JRCALC (AACE, 2019) for children; https://www.glasgowcomascale.org/).

| Eyes opening: |

| Verbal response: |

| Motor response: |

E: exposure

Look for any rashes, injuries, evidence of incontinence or vomiting that may help ascertain what is wrong. Temperature should also be considered at this stage.

Final stage

Finally, note any medic alert bracelets or chains that may indicate what is wrong with the patient. This primary survey is undertaken rapidly paramedics first set eyes on the patient.

Resuscitation and transport to hospital

The primary survey is designed so issues identified are managed in parallel with the survey. The range of equipment and drugs available to the paramedic, practitioner's scope of practice, availability of additional resources and proximity to the receiving unit will influence how much can be done before moving the patient.

JRCALC guidelines (AACE, 2019) and local protocols indicate guidance for the management of a variety of medical chief complaints. They will indicate the meaningful interventions required at each stage of the primary survey and at what point to consider rapid transport to hospital or request specialist support. Specific interventions for common presentations are discussed later in the series.

Following the introduction of specialist centres for trauma, myocardial infarctions, cerebrovascular accidents and vascular emergencies in most areas of the UK, not all patients are taken to the nearest accident and emergency department (A&E) (AACE, 2019). Some areas have BASICS (British Association for Immediate Care) doctors (Greaves and Porter, 2021) and advanced/critical care paramedics (College of Paramedics, 2018), who can assist with skills outside the scope of practice of the paramedic on scene. Therefore, it is important to understand local policies and procedures.

Paramedics should be aware that rapid transportation means transport to hospital not transfer to the ambulance. Ambulance departures should be delayed only be for procedures that cannot be carried out safely in a moving vehicle.

Primary surveys are repeated after intervention or on noticing deterioration of the patient until their care has been handed over. Often in a time-critical patient, a full secondary survey is not completed.

After a negative primary survey

If there is nothing immediately life threatening, then a more focused assessment of the patient can be undertaken to determine the most appropriate management and ensure the patient is not in fact primary survey positive and at risk of deteriorating.

This more in-depth assessment will also help to determine whether the patient has a time-critical condition that has not already been recognised or one that can be managed in primary care. Again, by following a structure, nothing will be missed.

As soon as a red flag is identified, management should be started. Time should not be wasted completing all elements of the secondary survey on scene if it the patient is found to require transfer to hospital for immediate management of the condition.

Secondary survey

This more in-depth assessment is known as the secondary survey. Using the acronym SOAPC, it includes Subjective and Objective observations which are then Analysed to formulate a Plan, and this information should be Communicated onwards as appropriate (Wardrope and Mackenzie, 2004).

A paramedic should have a good understanding of the pathophysiology of life-threatening conditions and the more common primary care conditions to help them recognise red flags and differential diagnoses. There are some prompts in the JRCALC clinical guidelines (AACE, 2019). There are also useful symptom sorter boxes in books such as those by ALSG (2010), Innes et al (2018) and Hopcroft and Forte (2020), which help paramedics to differentiate between a variety of conditions.

As with the primary survey, several resources can help paramedics understand how to take a patient history and carry out an assessment. The information that follows has been adapted from ALSG (2010), Blaber and Harris (2011), Innes et al (2018) and Thomas and Monaghan (2014) to suit the prehospital emergency environment and the equipment available.

Subjective assessment: taking a history

The subjective observations come from taking the history as they are the patient and/or carer's account of what has happened and the symptoms experienced.

There are various mnemonics to help ensure that nothing is missed when taking a history. An example is SOCRATES (Site; Onset; Character; Radiation; Associated symptoms; Time/duration; Exacerbation and relieving symptoms; Severity), which can be used to assess pain (AACE, 2019). Whichever is used, it is important to understand: the symptoms the patient is experiencing; the chronology of events leading up to the 999 call or primary care consultation; past medical and surgical history; medications, prescription and over the counter; compliance; allergies; pertinent family history; and social history.

The paramedic should be able to build a picture and start to identify conditions for a differential diagnosis. To help narrow down the conditions within the differential diagnosis, specific questions in the form of a systems review should be asked. The systems review should include direct questions that elicit a yes/no answer to help clarify the information already received and to ensure nothing is missed that may impact the differential diagnosis.

Objective assessment

The objective observations are obtained from the physical assessment of the patient. This assessment also helps to narrow down the differential diagnosis. It will include the general introduction and a focused assessment based upon the system(s) of the body impacted by the chief complaint. Dependent on the chief complaint and possible differential diagnoses, more than one system may require assessment.

All patients require a series of basic observations to form a baseline for further assessment and evaluation of management of the patient. Most of these form part of the primary survey. If they have not been done already, it is essential that they are done now. These include respiratory rate, pulse rate, capillary bed refill time, SpO2, blood pressure and temperature. Depending on the patient's history, a 12-lead ECG, BM, peak flow measurement or urinalysis may also be indicated.

General introduction

The patient's general appearance should be noted, including posture, position, any restlessness, skin discoloration, scarring, colour of the sclera and lips, and condition of the nails. If the patient is in their own environment, note clues as to the patient's general wellbeing and ability to cope with the tasks of daily living.

Systems assessments

Respiratory

The respiratory assessment begins with exposing the patient's upper torso. Remember patient dignity and use a chaperone if possible. Any accessory muscle use or sternal/subcostal/intercostal recession not visible in the primary survey can now be determined. Note any scarring, wounds, bruises, deformities, pacemakers or medication patches.

Palpate the chest, feeling for subcutaneous emphysema, crepitus, swelling or deformity; note any tenderness; and assess whether both sides of the chest are rising and falling equally. If the patient is not breathing very deeply, it may not be obvious that there is unequal rise and fall of the chest without palpation.

Next percuss in the intercostal spaces. Listen for changes in resonance between the different areas of the lungs.

Finally auscultate the lungs. Listen to ensure that there is equal air entry and for any accompanying noises. It is important to auscultate all lung fields as only one area of the lung may be affected. Figure 1 shows the position of each lobe of the lungs within the thoracic cavity.

For patient comfort, undertake all assessments on the front of the chest first then repeat on the back. This avoids the patient having to keep moving backwards and forwards.

Cardiovascular

When assessing the cardiovascular system, a respiratory assessment is carried out as above with some additions. While inspecting the patient, look for any signs of sacral and/or pedal oedema which might indicate heart failure. Check the pedal pulses as well as the radial pulses to ensure that there is no vascular compromise in the legs. Check the calves for tenderness and swelling as this may indicate a deep vein thrombosis.

Another indicator of heart failure is raised jugular venous pressure. Low jugular venous pressure indicates hypovolaemia. Box 3 describes how to assess jugular venous pressure.

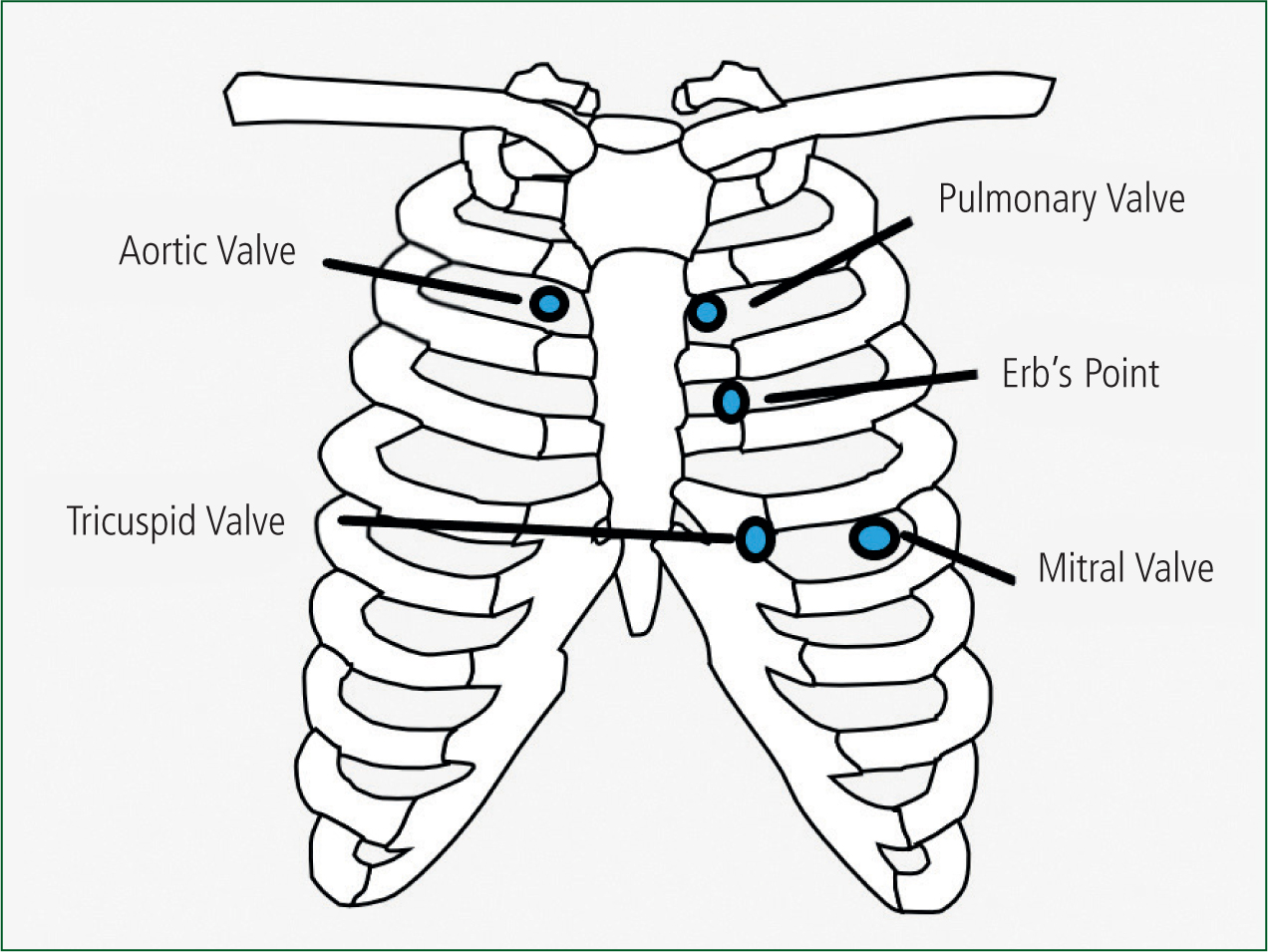

In addition to auscultating for breath sounds, the carotid artery should be auscultated to determine if there are any bruits. Finally, the heart should be listened to at the site of each of the valves (Figure 2). When auscultating, listen for heart sounds and any accompanying murmurs.

Abdominal, including gastrointestinal, genitourinary and reproductive

To undertake an effective abdominal examination, the patient needs to be lying supine. This allows the abdominal muscles to relax. The abdomen should be exposed from the xiphysternum to the symphisis pubis. Again, consider patient dignity and the use of a chaperone.

Begin by looking at the abdomen for any signs of distension, masses, scars or discoloration. Distension is caused by: fat; a build-up of fluid, gas or faeces; or a foetus in women. To assess symmetry of the abdomen, look from the feet and from the side.

For the next stages of the assessment, the abdomen is split into four quadrants to help ensure nothing is missed.

Auscultate the four quadrants to determine if bowel sounds are present. You may need to listen for up to 2 minutes before you can confirm that bowel sounds are absent (this time varies depending upon the textbook consulted). If they are high pitched or a tinkling sound is heard, this may indicate that there is an obstruction. Auscultate near the umbilicus to determine if there are any aortic bruits.

Palpation of the abdomen should begin in the quadrant away from any pain, leaving that quadrant until last. This helps to stop the patient from guarding in all areas of the abdomen. If there is an obvious pulsatile mass, do not palpate as this may be an aortic aneurysm.

Start with superficial palpation using a flat hand with a rocking motion to move any fat. Push down 1–2 cm. Note any masses, rigidity, guarding or tenderness. If the pain was not too great when palpating superficially, repeat the palpation deeper to help find any masses hidden by fat or to locate the borders of enlarged organs.

If the patient is complaining of pain in the lower right quadrant but displays guarding or tenderness in the lower left quadrant, this is known as Rosving's sign and indicates appendicitis. Appendicitis can also be indicated by rebound tenderness, psoas and obturator signs.

Other tests include Murphy's sign for cholecystitis.

Please consider the ethics of these tests: is it right to inflict pain when it will not change the management of the patient?

Patients with acute abdominal pain should be taken to A&E for further assessment with ultrasound, as this is a much safer and more accurate diagnostic tool than tests that elicit pain.

Finally, percuss the abdomen to ascertain the borders of the spleen, liver and bladder. These will only be discernible if they are enlarged. Percussion will also help to ascertain if any distension is fluid or gas.

Neurological

If a patient presents with a headache, visual disturbance or paraesthesia, then the nervous system should be assessed.

There are 12 cranial nerves (Box 4).

Next, assess the peripheral nervous system. This is done by assessing sensation, tone, power and coordination.

Sensation is assessed by using touch to determine equality in sensation in both limbs.

Tone is assessed by looking at the muscles. Is there any wastage? Can the patient flex and extend their arms and legs? As they move their arms and legs, do you notice any abnormality in the muscles as you hold the limbs.

Power is assessed by asking the patient to grip both of the paramedic's hands, then pull towards them and push away against resistance. Assess for pronator drift by asking the patient to raise both arms in front of them and then close their eyes. Both arms should stay still. Undertake myotomal assessment all major joints. If it is safe to do so, ask the patient to stand with their feet together and close their eyes. Any movement is abnormal.

Co-ordination is assessed by watching the patient walk: is the gait normal?

Proprioception and dysdiadokokinesis.

Testing proprioception involves placing a hand in front of the patient, asking the patient to touch a finger on this hand then touch their nose. They then repeat this with their eyes closed. For the legs, ask them to drag their heel down their shin with eyes open and then with eyes closed. Inability to repeat with the eyes closed indicates further investigation is required. Pass pointing can also be used to assess this.

To test for dysdiadokokinesis, ask the patient to place their hands palm to palm, then turn over the top hand. Keep turning the hand over as fast as possible. There may be a slight variation with the dominant hand being stronger.

Musculoskeletal

This article is dealing with medical complaints, not trauma. However, if the patient presents with non-traumatic limb or joint pain, this will still need assessing using the same methodology as for minor injuries—look, feel and move.

Various pathologies that present as limb, joint pain or paraesthesia that do not involve trauma. Examples include peripheral vascular disease, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis and multiple sclerosis.

Expose the painful area and look for any discoloration, swelling or deformities. Always assess the joint above and below the painful area as well.

Palpate the area starting away from the pain. Note any change in temperature, masses, crepitus and tenderness. Check for distal pulses and sensation.

Ask the patient to demonstrate the range of movement of the affected limb or joint. Compare this with the unaffected side. Check for passive movement and strength against resistance if it is not too painful.

Ear, nose and throat

This is more common in primary care. Check the throat and tonsils for discoloration and swelling. Palpate the lymph nodes around the head and neck to check for lymphadenopathy. Using an otoscope, examine the tympanic membrane.

Analysis: decision-making

Once the assessment is complete, findings will need to be analysed and a decision made on where to refer the patient. Does the condition require immediate assessment and management in hospital? Does the patient require immediate treatment and follow-up in the community? Do they require referral to primary care or community services? Does the patient require self-care and advice on what to do if their condition feels worse?

A good underlying knowledge of pathophysiology will help this decision-making process as well as enabling identification of immediately life-threatening conditions. The JRCALC clinical guidelines (AACE, 2019), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines and local guidance can help with some of these decisions. There are also early warning scoring systems (Royal College of Physicians, 2017; NICE, 2019) that are designed to help see the bigger picture and identify patients at a higher risk of deterioration.

If there is still uncertainty, do not be scared to ask a colleague for their opinion. Many ambulance services now employ paramedics in their emergency control rooms to provide guidance and advice to colleagues.

In line with NHS guidance (Department of Health and Social Care, 2021), decisions should be made in conjunction with the patient where practicably possible. If the patient lacks capacity, then a decision should be made in the best interests of the patient, unless there is a valid power of attorney or advance decision relating to the situation (Mental Capacity Act, 2005).

Plan

Once decisions are made, any necessary treatment and referrals should be undertaken.

Communication and handover

The assessment, decision-making and any treatment need to be clearly documented in line with local guidance (Health and Social Care Information Centre and NHS England, 2014). With the advent of electronic patient reporting, some of this information is automatically passed to the receiving hospital or patient's GP. It is important to ensure verbal handover is also done (unless the patient is left with advice on self-care and what to do if their condition worsens). This will help prevent any pertinent information being missed.

A recognised handover tool such as SBAR or ATMISTER will help to ensure all pertinent information is handed over (Box 5).

| SBAR |

|

|

| ATMISTER handover tool |

|

|

If the patient is being discharged without onward transport to another healthcare provider, it is imperative that the patient and any carer understand any advice given to them regarding deterioration and who to contact if anything changes. Ideally, this should be written down. This is known as safety netting.

Conclusion

By following a methodical structure to patient assessment and management, it is less likely that a life-threatening condition will be overlooked.