Paediatric assessment is a challenging skill in the pre-hospital setting. Pre-hospital clinicians are generalists and do not have the specialised paediatric training that hospital and primary care clinicians will have. The fact remains, however, that demand for this skill is high. To take London as an example, 5% of all patients attended to by the London Ambulance Service NHS Trust (LAS) last year were under the age of four years (93 626 incidents). To put this in context, LAS clinicians attend more children under the age of four years than the sum of all patients in cardiac arrest, with confirmed myocardial infarctions and fast positive strokes. Paediatric patients are challenging to treat and it is therefore essential that clinicians are making appropriate, safe decisions based on their accurate clinical assessments.

Historically, studies suggest that confidence and aptitude amongst pre-hospital clinicians in assessing and treating paediatrics has been low. Research in the UK is sparse; however, American research has shown that pre-hospital clinicians are not confident treating paediatric patients and have the least confidence treating patients under two years old (Gausche et al, 1990). This lack of confidence may affect paediatric care as is evidenced by a UK study where pre-hospital clinicians have not adequately monitored or treated paediatric patients (Fisher and Vinci, 1995). This has been supported by more recent American research that reports pre-hospital clinicians have the lowest accuracy in assessing infants (Foltin et al, 2002). The research indicates that there is a potential to improve the assessment and treatment of this challenging age group.

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health recognised the difficulty of the pre-hospital paediatric assessment and a review was undertaken. As a result, in 2010, the LAS adopted a new policy, stipulating that all patients under the age of two years should be conveyed to hospital, regardless of their condition. Furthermore, any patient between two and five years old should be referred to a general practitioner (GP) if not conveyed. This Paediatric Care Policy recognises the challenges of the pre-hospital paediatric assessment and the difficulty gaining an accurate history from carers. In addition, the policy ensures that the GP will be aware of all contacts with health services either by direct referral from the ambulance service or by notification from the hospital. In essence, it has sought to rectify any clinical or safeguarding risks associated with leaving a paediatric patient at home, based solely on a pre-hospital clinician's assessment.

More specifically, detecting and treating paediatric patients presenting with a serious condition is paramount to prevent decompensation (Woollard and Jewkes, 2004). Paediatric physiology differs from adults, as they can show few signs of critical illness, and then their deterioration can occur ‘rapidly, catastrophically, and irreversibly’ (Woollard and Jewkes, 2004). Waiting to assess and treat paediatric patients at hospital could be too late. These patients are likely to present to the ambulance service and may require treatments such as drug therapy, continual monitoring and a pre-alert to the receiving hospital (Paediatric Formulary Committee, 2012). The Paediatric Care Policy provides protection for patients who would otherwise be left at home, but cannot protect against the requirement for seriously ill patients to be properly assessed and treated by pre-hospital clinicians.

It is noteworthy, however, that research into this field is notoriously limited (Leonard et al, 2012). Changes in equipment and the widespread uptake of national guidelines from the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) (Roberts et al, 2005) postdate most of the research into this field. With a dearth of literature following the effects of both local and national changes, this article aims to return to the issue of paediatric pre-hospital care, in order to review the effectiveness of modern pre-hospital practices. To do so, a clinical audit of the care of paediatric patients with difficulty in breathing was undertaken using the LAS's patient report forms (PRFs).

Paediatric respiratory assessment

This article will specifically address respiratory assessments undertaken for children under three years of age. This age group was selected as the research demonstrated that pre-hospital clinicians are less confident and less proficient at assessing these patients (Fisher and Vinci, 1995). In addition, difficulty in breathing in patients under three years old, accounts for just under 4 000 incidents in the LAS yearly, rendering a paediatric respiratory assessment a relatively frequent procedure in the career of a pre-hospital clinician.

Besides frequency, there is a physiological explanation for the selection of the respiratory assessment. Unlike adults, who commonly suffer from primary cardiac arrests, children usually suffer cardiac arrests secondary to hypoxia (Macqueen et al, 2012); therefore, if left untreated hypoxia has significant morbidity and mortality (Jewkes, 2006). The need to recognise deteriorating respiratory function and correct it, therefore, becomes essential to their survival. Consequently, the respiratory assessment is an integral part of a full paediatric assessment, to ensure pre-hospital clinicians react quickly to correct hypoxia. Furthermore, a poorly conducted respiratory assessment could unnecessarily delay treatment for an underlying respiratory pathology.

Methodology

A retrospective criterion-based clinical audit was undertaken of 253 PRFs collected from the end of June 2011 to the end of July 2011, where the pre-hospital clinician identified and coded dyspnoea (difficulty in breathing) and the patient's age was under three years. This included all PRFs from this time period, London-wide. The aim of this clinical audit was to assess the quality of care delivered by the LAS, in relation to specified national guidelines for pre-hospital paediatric respiratory assessments (JRCALC, 2006).

When clinically managing difficulty in breathing, UK ambulance services follow the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee Guidelines for use in UK ambulance services (JRCALC, 2006). These guidelines stipulate that treatment for respiratory distress should commence before conveyance to hospital so this assessment should be undertaken whilst in pre-hospital care. As part of the respiratory assessment, the ‘Medical Emergencies in Children’ section stipulates the requirement to measure respiratory rates, inspiratory or expiratory noises (through auscultation) and pulse oximetry (JRCALC, 2006).

Inclusion criteria

Respiratory rate forms an essential part of a respiratory assessment and is part of the Paediatric Index of Mortality (Slater et al, 2003). Deviation in normal respiratory rates is a predictor of mortality for paediatrics in intensive care units (Shann et al, 1997), is used as a tool of severity for children diagnosed with community acquired pneumonia Harris et al, 2011), and forms part of the primary survey on the paediatric triage tape (Wallis and Carley, 2006). An assessment of inspiratory and expiratory noises, generally found on auscultation is similarly important. Auscultation should be recorded to ascertain if there is an expiratory wheeze (a symptom of asthma), or stridor (a symptom of an upper respiratory obstruction) (Hilliard et al, 2003). Drug therapies can be started as a result of the clinical assessment, for example: oxygen therapy or assisted ventilation if respiratory rates deviate from normal levels; Salbutamol and Ipratropium bromide for an expiratory wheeze (JRCALC, 2006). Failure to complete an adequate clinical assessment may result in drug therapy being omitted and consequently delay treatment.

Oxygen saturations are also a vital assessment tool. In hospitals, paediatric patients’ length of stay is reduced if oxygen saturations are taken at triage (Choi and Claudius, 2006). A paediatric patient's oxygen saturation level has a significant impact on a child's likelihood of being admitted (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2006) and forms an integral part of the decision to provide children with home oxygen (Balfour-Lynn et al, 2009). As a result of this evidence and also in accordance with the Paediatric Index of Mortality (Slater et al, 2003), JRCALC advises oxygen saturation levels should determine the administration of oxygen, maintaining paediatric patients at a minimum of 95% (JRCALC, 2006) unless there is a clear patient specific protocol which indicates otherwise. Guidelines also state that assisted ventilation should be considered based solely on oxygen saturations remaining under 90% after 30–60 seconds of high flow oxygen (JRCALC, 2006). It is difficult to assess reduced saturations using any other assessment tool, for example visible central cyanosis occurs at 85% oxygen saturations (Rabi et al, 2006), a level that is a significant predictor of mortality (Djelantik et al, 2003) and well below a level at which treatment should commence (JRCALC, 2006).

Results

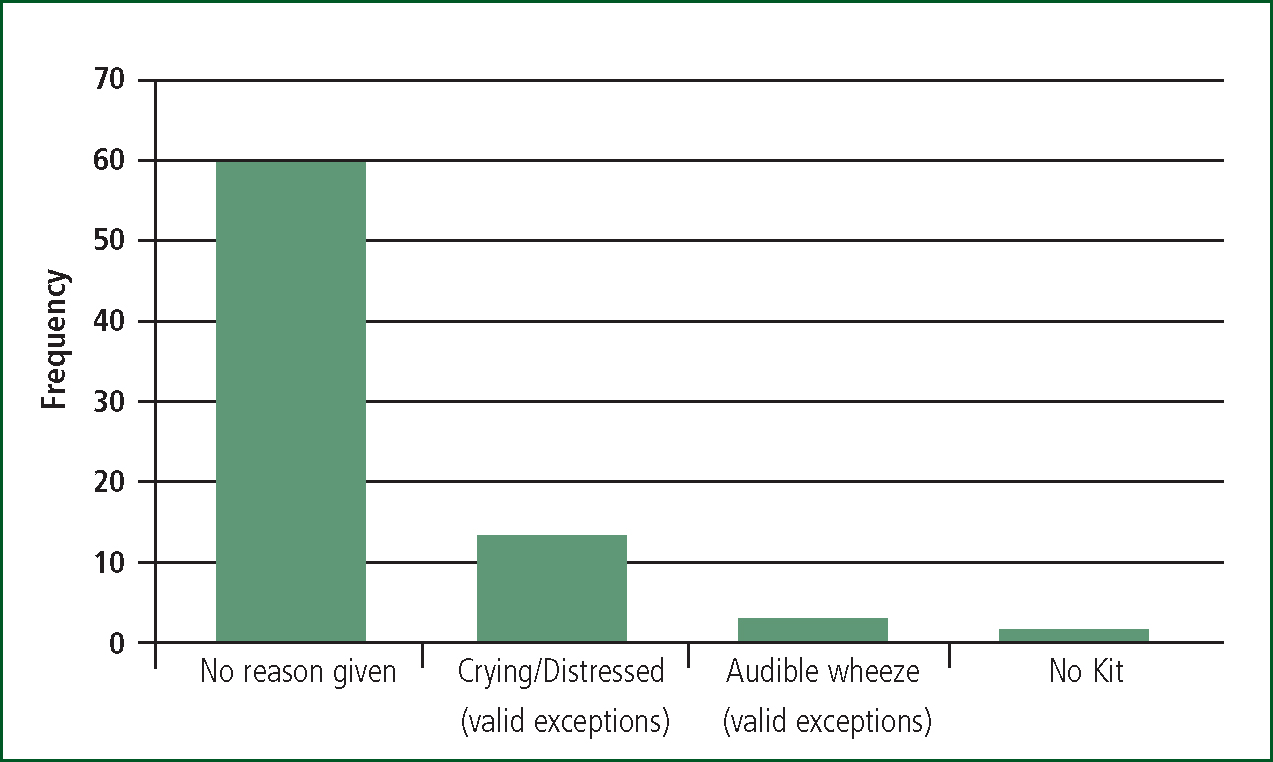

Auscultation attempted

Pre-hospital clinicians documented clinically valid exceptions, such as patient crying, for not attempting auscultation for 6% of patients (n=14). Of the remaining 239 patients, 74% were auscultated (n=178), leaving 26% of patients (n=61) with no documentation regarding attempted auscultation. More than four times the number of patients had no assessment without an explanation provided, as shown in Figure 1ne. This paper assumes that a lack of documentation means that the assessment was not carried out. The next largest group is valid exceptions.

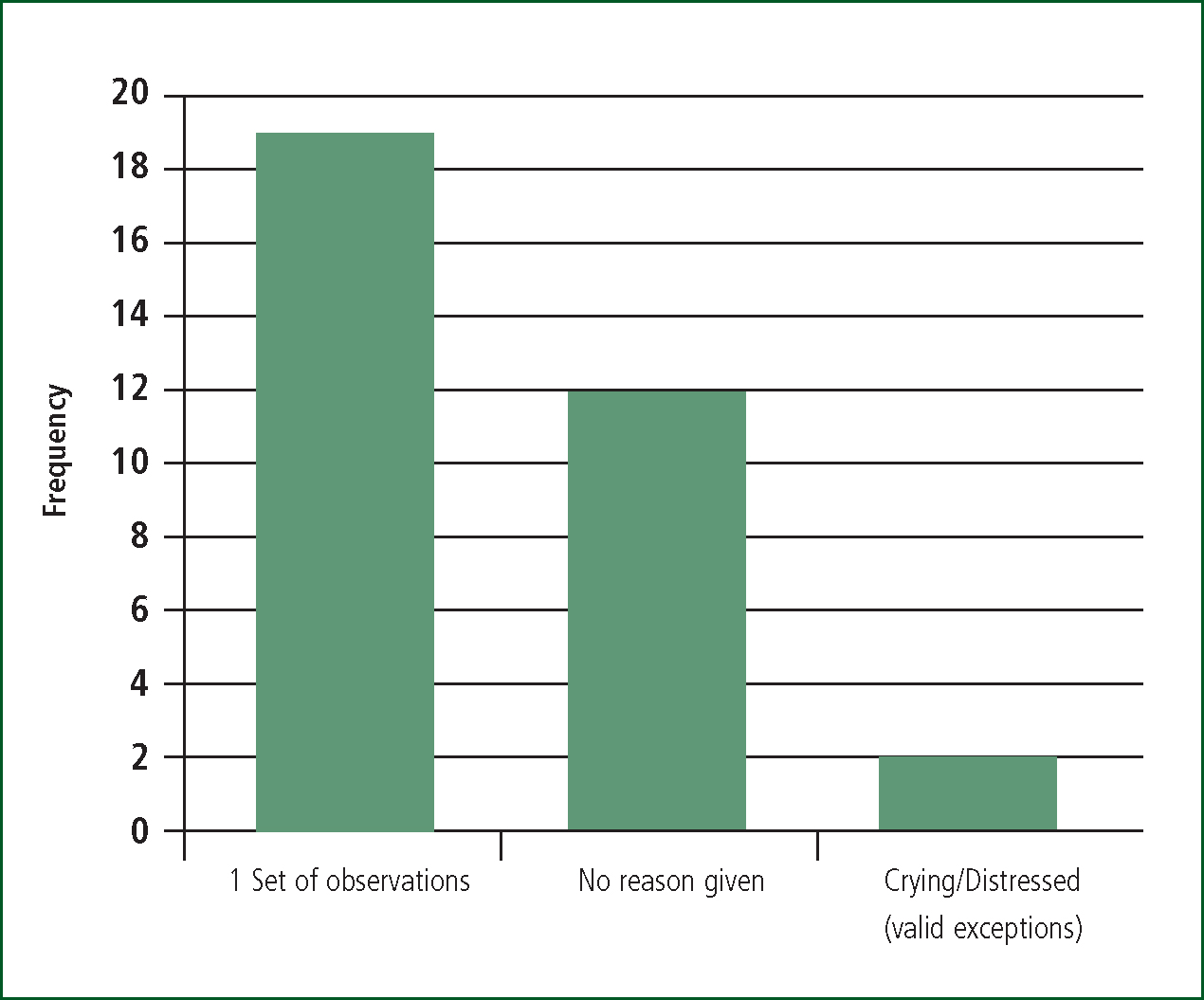

Two respiratory rates documented

For two patients it was documented that the crew felt unable to assess the patients’ respiratory rate as the patient was distressed or crying. Of the remaining 251 patients, 88% of patients (n=220) had two respiratory rates recorded. Two respiratory rates were not recorded for 12% of patients (n=31); 19 of these patients did have their respiratory rate as part of their initial assessment. Therefore, 12 patients with difficulty in breathing had no respiratory rate documented and no reason given (see Figure 2). The range of initial respiratory rates varied between 10 and 82, with a median rate of 40 breaths per minute. The low number of exceptions suggests that this assessment is relatively easy to perform on this age group, perhaps because it can be performed whilst observing the child from afar.

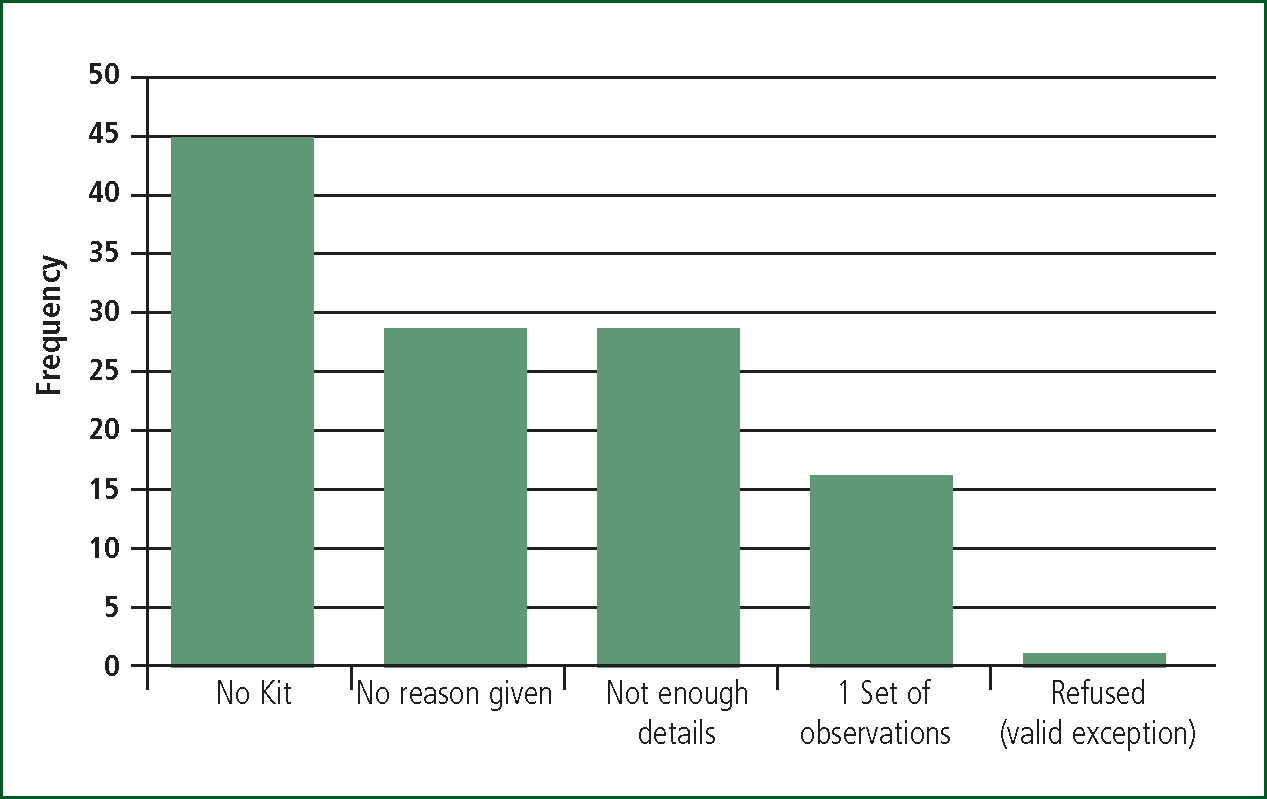

Two oxygen saturation recordings

An oxygen saturation recording was not documented for one patient where a clinically valid reason was recorded. Two oxygen saturation recordings were documented for 52% of the remaining patients (n=131). Therefore, 48% of patients (n=121) did not have two oxygen saturation recordings documented. The main reason documented was ‘no kit’, accounting for 37% (n=45) of the non-compliance, with 24% (n=29) having no reason given. See Figure 3 for further details.

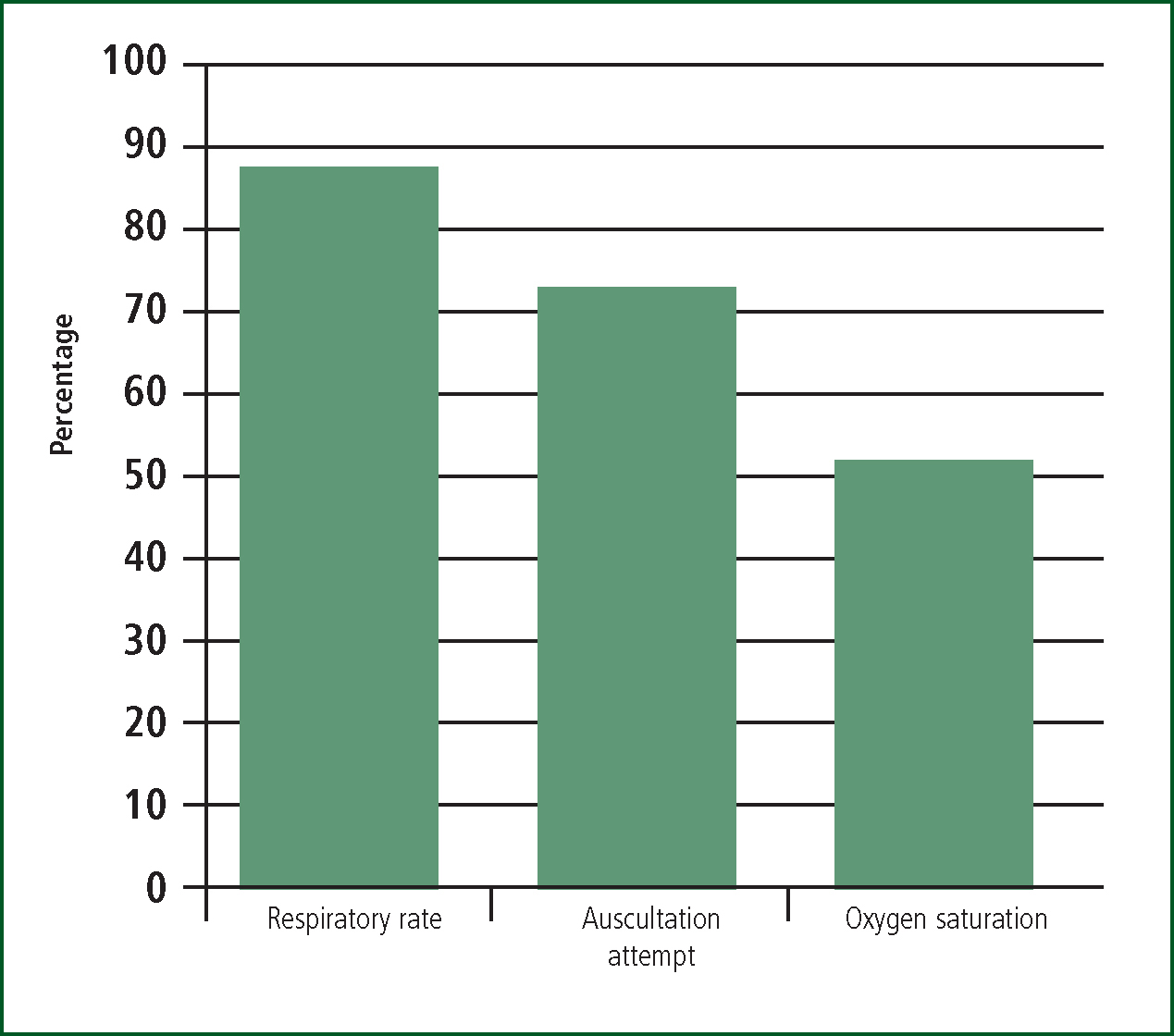

Overall compliance

99 patient report forms documented two respiratory rates, two oxygen saturations, and an auscultation attempt (or had a valid exception for not doing so), that accounts for just 39% of patients receiving the full assessment, when appropriate. The remaining 61% (n=154) lacked at least one aspect of care, mainly oxygen saturation documentation. Figure 4 demonstrates the overall compliance to each assessment showing that two respiratory rates were documented most often and oxygen saturations were documented least often. This has highlighted a requirement to improve the respiratory assessment, with the documentation of oxygen saturations requiring the most improvement.

Conclusions

This clinical audit, on the backdrop of sparse current research, intended to address the levels of compliance to a simple paediatric respiratory assessment. The findings suggest a mixed conclusion. The majority of patients (61%) are not receiving a comprehensive respiratory assessment despite being identified by the pre-hospital clinician as having difficulty in breathing. There does appear to be improvements since the literature published in the 1990s; however, there is no previous similar research to make a valid comparison with.

The recording of respiratory rates is the aspect of care that crews are undertaking most often. It is important that this measure is completed as the result can be compared to JRCALC's age appropriate respiratory rates. If a child is breathing too rapidly or too slowly, when combined with an assessment of perfusion and work of breathing, it can indicate significant pathology and can contribute to the treatment plan and appropriate care pathway for the patient. Only a small number (4%) of pre-hospital clinicians did not give a reason for not recording a respiratory rate. The wide range of respiratory rates suggests that pre-hospital clinicians are assessing rates rather than guessing or relying on estimates based on the age of the child.

Auscultation was not reported for almost one quarter of PRFs. For these patients it was not possible to determine whether drug therapies, which are indicated in patients with an expiratory wheeze, should have been given. An expiratory wheeze is mainly discovered on auscultation with only the most severe patients having an audible wheeze.

‘A lack of pulse oximetry should not deter pre-hospital clinicians from otherwise completing a full assessment’

Oxygen saturations were recorded in just over half of the PRFs, with lack of equipment accounting for the greatest proportion of non-compliance. A lack of pulse oximetry creates a risk—those critically ill children, who appear to be compensating, could be harbouring dangerously low oxygen saturations with no visible signs and thus excluding them from necessary corrective management to prevent prolonged hypoxia. This finding highlights an issue as to whether the LAS is providing the most appropriate equipment to monitor and manage paediatric patients.

Limitations

It is acknowledged that these three observations in isolation do not extensively account for a full respiratory assessment. These observations were chosen as they form part of JRCALC's Breathing Management and allow for the indication of pre-hospital interventions. It is also acknowledged that general appearance (perfusion), work of breathing, tone, level of consciousness, temperature and heart rate allows the pre-hospital clinician to build a picture of the severity of the infant's condition; however, this is beyond the remit of this audit. This clinical audit used patient report forms from the London Ambulance Service only and local policies and procedures, which limit the conclusions to London only. Furthermore, it is acknowledged that the guidelines of JRCALC 2006 have been superseded; however, the 2006 guidelines were the prevailing guidelines at the time of the audit.

Discussion

It is reassuring that the majority of patients are receiving at least a partial assessment in accordance with the JRCALC guidelines, showing improvement since the most recently published literature. It is of note, however, that these three observations are the most amenable to formal audit and do not constitute a full respiratory assessment. These three simple assessments, at the very least, should be undertaken for every patient and any exceptions noted appropriately. Respiratory rates and auscultation attempts require further improvement to achieve maximum compliance; however, the recording of oxygen saturations lags even further behind.

The supply of paediatric pulse oximetry has been the source of some debate and research, both for ambulance services and in GP surgeries (Roberts et al, 2005). It seems there is an inconsistency between ambulance Trusts, with some supplying paediatric probes and some not (Roberts et al, 2005). Without this equipment, clinicians could be forgoing the opportunity for an early diagnosis of hypoxia, which could delay recognition and treatment of a child on the brink of decompensating. This audit highlights a systemic ongoing issue with the way in which equipment availability is managed.

A lack of pulse oximetry should not deter pre-hospital clinicians from otherwise completing a full assessment. A respiratory assessment should be more extensive than the remit of this audit. Moreover, in the absence of pulse oximetry, all other available observations become more important as they are more heavily relied upon to measure the severity of a child's difficulty in breathing. It also affords these vulnerable patients a chance to be assessed and treated to the best standards of care.

The role of a pre-hospital clinician has changed considerably, with ever more responsibility and decisions being made in a pre-hospital setting. It has promoted intellectual rigor and a responsibility to remain current, evidenced by the formation of the British Paramedic Association (later the College of Paramedics) in 2001, the first professional body for paramedics practising in the UK. The level of care promoted through JRCALC guidelines and training has improved (Roberts et al, 2005). However, paediatric care is an area where further improvement is needed. By continuing to advocate the importance of paediatric assessments and providing appropriate equipment, there should be no hindrance from providing paediatric patients the quality of care they require, every time.

‘By continuing to advocate the importance of paediatric assessments and providing appropriate equipment, there should be no hindrance from providing paediatric patients the quality of care they require, every time.’